Émile Gilliéron

Émile Gilliéron père | |

|---|---|

Photographed c. 1915 | |

| Born | Louis Émile Emmanuel Gilliéron October 24, 1850 Villeneuve, Switzerland |

| Died | October 13, 1924 (aged 73) Athens, Greece |

| Education | Kunstakademie, Munich École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris |

| Known for | Archaeological reconstructions, especially of frescoes from Knossos and Tiryns |

| Spouse |

Joséphine Zoecchi (m. 1884) |

| Children | Émile Gilliéron fils |

| Relatives | Jules Gilliéron (brother) |

| Patron(s) | German Archaeological Institute at Athens Heinrich Schliemann Arthur Evans |

Louis Émile Emmanuel Gilliéron (1850–1924), often known as Émile Gilliéron père to distinguish him from his son, was a Swiss artist and archaeological draughtsman best known for his reconstructions of Mycenaean and Minoan artefacts from the Bronze Age. From 1877 until his death, he worked with archaeologists such as Heinrich Schliemann, Arthur Evans and Georg Karo, drawing and restoring ancient objects from sites such as the Acropolis of Athens, Mycenae, Tiryns and Knossos. Well-known discoveries reconstructed by Gilliéron include the "Harvester Vase", the "Priest-King Fresco" and the "Bull-Leaping Fresco".

From 1894, Gilliéron maintained a business producing replicas of archaeological finds, particularly metal vessels, which were sold to museums and collectors across Europe and North America. This enterprise grew particularly successful after Gilliéron introduced his son, also named Émile, into the business around 1909. The Gilliérons' work has been credited as a major influence on the public and academic perception of Greek antiquity, particularly Minoan civilisation, and with disseminating the influence of ancient cultures to modernist writers, artists and intellectuals such as James Joyce, Sigmund Freud and Pablo Picasso.

Many of Gilliéron's restorations were made from highly fragmentary evidence, and he often made bold, imaginative decisions in reconstructing what he believed to be the original material. In several cases, his hypotheses have been challenged or overturned by more recent study. Gilliéron frequently muddied the distinction between his own restorations and the original material, and was criticised in his day for overshadowing ancient material with his own creations. He was also likely involved in the illegal export of forged antiquities from Greece, and has been accused of direct involvement in the manufacture of faked objects.

Early life and education

Louis Émile Emmanuel Gilliéron was born on 24 October 1850 in Villeneuve, Switzerland,[1] the second of four sons of Jean-Victor Gilliéron and Méry Ganty.[2] His father, a language professor in the Progymnasium in La Neuveville near Bern, and later in the Gymnasium for girls in Basel, was also a respected amateur geologist and paleontologist.[3] Émile attended the Progymnasium in La Neuveville,[4] then studied at the trade school (Gewerbeschule) in Basel from 1870 to 1872.[5] In 1870–1871 he was an apprentice in the lithography studio of Johannes Jakob Tribelhorn at Saint Gall,[4] an experience to which he later attributed the exceptional precision of his drawings of ancient artefacts.[6] In 1872 he moved on to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, where he studied with Johann Georg Hiltensperger.[7] He completed his education in 1874–1875 at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, in the studio of the academic painter Isidore Pils.[8] While at the École des Beaux-Arts he also studied ancient art with the archaeologist Léon Heuzey, a member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres and a conservator of antiquities at the Louvre.[9]

Following the death of Pils in 1875, and with the encouragment of Heuzey, Gilliéron accompanied his older brother, the classicist Alfred Gilliéron, on a voyage to Albania and Greece.[11] The brothers arrived in Athens in the autumn of 1876, and by the following year Émile had established himself in the city as an artist and art teacher.[12] He purchased a house at 43 Skoufa Street in the fashionable Kolonaki district, which served as his home and atelier throughout his life.[13] Among the students to whom he gave lessons in drawing and painting in the 1880s were the sons of George I of Greece, whose patronage gave him access to the upper echelons of Greek society.[14] George's younger son Nicholas enjoyed the lessons and looked back on Gilliéron with fondness, and his older brother, the future king Constantine, later served as the president of the Archaeological Society of Athens.[15] In 1899–1900 Gilliéron taught the Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico, who was born and educated in Greece, and whose paintings drew on the archaeological and mythological themes characteristic of Gilliéron's work.[16] According to de Chirico, his lessons consisted primarily of copying "a lot of prints", possibly those of archaeological finds Gilliéron was engaged in restoring and replicating.[17]

Early archaeological work

Within a few years of his arrival in Athens Gilliéron had already begun to specialize in the work for which he was best known: that of an archaeological draughtsman.[18] Writing after his death in 1924, the archaeologist Gerhart Rodenwaldt, director of the German Archaeological Institute at Athens, suggested that Gilliéron lacked the artistic creativity needed to make a living purely as a creative artist, and this, together with the economic conditions in Athens at the time, compelled him to turn more and more to archaeological illustration. According to Rodenwaldt, "he devoted the full intensity of his ebullient disposition to this work, although he never fully got over the tragedy of abandoning his original creations".[19] Nevertheless, while commercial archaeological work became the focus of his business, he continued to produce landscapes and other paintings for his private satisfaction, most of which remained in the possession of his family.[20]

Gilliéron's contemporaries and the archaeologists who worked with him praised the accuracy of his draughtsmanship and his ability to reproduce the fine decoration on objects such as vases and gemstones. They also valued his skill as a painter, which he relied upon to restore the appearance of damaged objects and to document the original colouring of ancient sculptures.[21] These skills were in demand, as photography was expensive and the results difficult to guarantee; photography was also generally unable to convey colour, whereas Gilliéron painted in bold watercolour, sometimes at a 1:1 scale.[22] His fees were accordingly high.[23]

Gilliéron's archaeological drawings and paintings began to appear in the publications of the German Archaeological Institute as early as 1879.[24] His close association with the Institute continued throughout his career: among the German archaeologists with whom he collaborated were Wilhelm Dörpfeld, Ernst Fabricius, Adolf Furtwängler, Paul Hartwig, Georg Karo, Gerhard Rodenwaldt, Theodor Wiegand, and Franz Winter.[25] One of his first clients was Heinrich Schliemann, the excavator of the sites of Troy, Tiryns and Mycenae, for whom he worked as a painter, draughtsman, and conservator from 1877 until Schliemann's death in 1890.[1] In 1884, Schliemann hired him to produce reconstructions of the frescoes he had unearthed at the Mycenaean citadel of Tiryns in the Argolid; Gilliéron reconstructed one fresco to show a man dancing upon a bull, an image which became famous as the cover illustration of Schliemann's volume publishing the results of his excavations.[26]

In the 1880s Gilliéron produced a series of drawings and watercolours of vases, sculptures, and other objects discovered on the Acropolis of Athens during the excavations directed by Panagiotis Kavvadias.[27] Many of his reproductions of vase paintings appeared after his death in the publication by the German Archaeological Institute of the ceramic finds from the Acropolis, which used his drawings when photographs alone were inadequate to illustrate the decoration of the vessels.[28] His large-scale watercolours of sculpture, including the poros architectural sculpture from the Hekatompedon and other Archaic buildings on the Acropolis, and the marble korai and other works found in the debris associated with the Persian invasion of Athens in the early 5th century BCE, provided an important record of the original colouring of these objects, which was often clearly visible at the time of excavation but deteriorated quickly thereafter.[29] These paintings gained wide exposure outside Greece, as Gilliéron was commissioned to produce additional copies for private collectors and museums. A collection of twenty-six watercolours and tinted photographs, originally made in 1883 and 1886 for the American architect and art critic Russell Sturgis, were later acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where they were displayed in 1891 in an exhibition on ancient polychromy organized by Edward Robinson, the museum's curator of classical antiquities.[30] A similar exhibition at the Art Institute in Chicago in 1892 also included watercolours and photographs loaned by Sturgis.[31] After Robinson moved to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1906, that institution too purchased hundreds of paintings, replicas, and other objects from Gilliéron and his son, including watercolours of the architectural sculpture from the Acropolis.[32] Other copies were acquired by the Humboldt University in Berlin.[33] Some of Gilliéron's watercolours of sculpture from the Acropolis were exhibited in the Greek pavilion at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889, greatly enhancing his profile and reputation.[34]

In 1886 Gilliéron was hired to assist in the rescue excavation of Psychro Cave in eastern Crete, conducted under the Syllogos of Candia, a local archaeological society. Gilliéron made painted reconstructions of the bronze votive objects deposited in the cave, many of which were in damaged or fragmentary condition.[35] In 1888–1889 he worked with Paul Wolters at the Theban Kabeirion in Boeotia. Wolters, then the second secretary of the German Archaeological Institute and later a professor at the University of Munich and director of the Munich Glyptothek, remained a close friend and supporter for the rest of Gilliéron's life.[36] For a report published in 1893 Gilliéron illustrated the pottery found by Valerios Stais during the excavation of the tumulus of the Athenians at Marathon in 1890–1891.[37] Following the discovery of the painted metopes of the Temple of Apollo at Thermon in 1898, he produced a group of preliminary drawings published in 1903, followed by more complete watercolors of the mended fragments published in 1908, which were widely reproduced in handbooks on Greek art.[38] His work as a draughtsman was not confined to antiquities: in 1880 he accompanied Spyridon Lambros to Mount Athos in order to make copies of the frescoes of the Byzantine painter Manuel Panselinos in the church of Protaton at Karyes,[39] and at some point before 1885 he was hired by the Marquess of Bute to copy the poorly preserved Christian frescoes in the Parthenon and the church of the Megale Panagia in Athens, as well as other paintings at Mistra in Laconia.[40]

Although Gilliéron was active chiefly in Greece, he occasionally worked in other Mediterranean countries as well. In 1893 he was commissioned by Carl Robert, who had recently become the director of the archaeological museum at the Martin Luther University in Halle, to make copies of Roman panel and wall paintings from Pompeii and Herculaneum for the museum collection. Robert had received a donation from Halle banker Heinrich Franz Lehmann to fund the work, and had been referred to Gilliéron by their mutual friend Paul Wolters.[41] Gilliéron made two trips to Italy: during the first, in 1893, he produced watercolor copies of six ancient paintings on marble panels in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, five of which had been found at Herculaneum and one at Pompeii.[42] His work was supervised by August Mau, an excavator at Pompeii and an authority on Roman painting, who approved the accuracy of the copies.[43] Several of the marble panels had been known since the 18th century and they were widely described as "monochrome" paintings, but Gilliéron's reproduction of the surviving traces of color allowed Robert to recognize them as polychrome works, nearly a century before this conclusion was widely accepted by other scholars.[44] Gilliéron himself suggested a second trip to Italy in the summer of 1896, perhaps because the unsettled political situation in Greece, on the eve of the Greco-Turkish war of 1897, may have disrupted some of his other projects.[45] During this visit he made copies of six additional Pompeiian wall paintings with mythological subjects, some in museum in Naples, others still in situ at the archaeological site.[46] For the German Egyptologist Friedrich Wilhelm von Bissing Gilliéron also made paintings of the Hellenistic–Roman tombs at Kom el-Shogafa in Alexandria, Egypt.[47]

Reproductions of archaeological artefacts

From 1894, Gilliéron established a business, in collaboration with the German metalworking firm Württembergische Metallwarenfabrik Geislingen (WMF) of Geislingen an der Steige, manufacturing replicas of archaeological artefacts for sale to museums.[1] A particular area of focus was the production of replicas of metal objects, using electrotyping from moulds made from the originals. According to Wolters, Gilliéron was as interested in the technical problems as he was in the artistic ones, and in the case of damaged originals his reproductions went beyond mere copies by reuniting broken fragments and restoring missing pieces.[48] The creation of these replicas led to a better understanding of ancient manufacturing techniques, and their distribution had a far-reaching effect on archaeological teaching.[49] Some of his first endeavours with this technique were copies of the Vapheio Cups, two gold cups discovered by the archaeologist Christos Tsountas in a Mycenaean tomb in Laconia in 1888.[50] Gilliéron reproduced the cups with the assistance of the Swiss metalworker Jules Georges Hantz, director of the Musée des arts décoratifs in Geneva, first in 1894 for Salomon Reinach, the curator of the French National Archaeological Museum, and subsequently for other customers as well.[51] An exhibit of his replicas of objects from Mycenae was awarded a bronze medal at the Exposition universelle in Paris in 1900.[52] By 1903, Gilliéron's company sold 90 different electrotyped Mycenaean artefacts, all manufactured by WMF; this figure rose to 144 by 1911 when Minoan artefacts were added to the list. An illustrated catalogue of the objects for sale was published in German, French, and English, with an introduction by Wolters, which described the original artefacts in detail and vouched for the accuracy of the reproductions.[53] In 1918, a Gilliéron Vapheio Cup was offered for sale for 75 German Reichsmarks, approximately equivalent to £1500 in 2019,[54][a] while the most expensive item offered in 1914 was a copy of a bull's-head rhyton from Knossos, priced at 300 Reichsmarks.[55] The firm also produced plaster casts of ancient sculpture, including korai from the Athenian Acropolis; some of these, painted to illustrate their original colouring and sold to the Metropolitan Museum in New York, have been placed on permanent loan to the Museum für Abgüsse Klassischer Bildwerke ('Museum of Casts of Classical Statues') in Munich.[56]

Olympic Games in Athens

Gilliéron took an active role in the promotion of the modern Olympic games in Athens, and the iconography that he helped to establish for the games drew heavily on ancient Greek art.[57] The most widely distributed of his works were two series of commemorative postage stamps, the first issued in conjunction with the first modern Olympic games in 1896 and the second with the intercalated "Mesolympic" games in 1906. The stamps were the product of a collaboration between the archaeologist and numismatist Ioannis Svoronos, who chose the subjects; Gilliéron, who drew the designs; and the artist and engraver Louis-Eugène Mouchon, who engraved the metal plates.[58] The stamps of 1896, which were printed in France and released to coincide with the opening of the games on 6 April (O.S. 25 March), included depictions of the Nike of Paionios and the so-called Hermes of Praxiteles, two works of sculpture recently discovered in the excavations at ancient Olympia, as well as a statue of a discus thrower traditionally attributed to the Greek sculptor Myron. Other stamps bore views of the Athenian Acropolis and the recently restored Panathenaic Stadium, and a Panathenaic amphora decorated with a figure of Athena.[59] The sale of the stamps raised over 400,000 drachmes for the Olympic committee.[60]

The stamps produced for the games in 1906, created by the same three men and printed in England, included images of individual athletes and athletic events drawn from ancient vase paintings, coins, and works of sculpture. A scene of wrestlers, for example, was taken from an Athenian red-figure krater depicting the legendary wrestling match between Heracles and Antaeus, while a stamp with a figure of a discus thrower and a tripod reproduced the device on a coin from the island of Kos.[61] Many of Gilliéron's designs were based not on the ancient works directly, but on line drawings in the Dictionnaire des Antiquités Grecques et Romaines by Charles Daremberg and Edmond Saglio, a French encyclopedia of the ancient Greek and Roman world published in ten volumes between 1877 and 1919.[62]

For the 1896 Olympics Gilliéron also designed the cover of the program of events and the official report of the games. His painting combined ancient and modern Greek motifs — a view of the Acropolis and other ancient Athenian monuments, allusions to works of classical art, a modern Greek flag, and a figure of a woman in traditional Greek dress holding a victory crown of olive — and was later used as a poster by the International Olympic Committee.[63] For the 1906 games he painted a series of postcards, including both representations of actual events in the stadium at Athens and imaginary compositions of ancient or allegorical figures.[64] He also created preliminary designs for trophies, most of which remained unrealized. Some were replicas of ancient vessels, such as a Mycenaean cup found by Schliemann in Grave Circle A at Mycenae and a kantharos from the Theban Kabeirion.[65] A series of circular plaster reliefs in the Gilliéron archive at the French School at Athens depict events in the pentathlon and seem to have been models for the decoration of proposed trophy cups; these, like the postage stamps, were based on ancient vase paintings and other works of art.[66]

Knossos and later career

In the spring of 1900, the British archaeologist Arthur Evans was excavating the Bronze-Age ruins – which he named the "Palace of Minos" – of the Minoan site of Knossos on Crete.[34] Gilliéron was visiting Knossos on 1 May [O.S. 18 April], while Evans's draughtsman, Yannis Papadakis, was in the process of removing some of the first fresco fragments to be discovered in the so-called "Throne Room" of the palace: Gilliéron recognised the outline of a griffin in some of the fragments, which became an established part of Evans's reconstruction of the room's decoration.[67] Evans wrote in his diary on 23 April [O.S. 10 April] that Gilliéron "began immediately to sort the fresco fragments like jigsaw puzzles" upon his arrival at Knossos.[68]

Evans found a number of frescoes requiring complex reconstruction, which he felt to be beyond the skill of Papadakis;[23] he instead contracted Gilliéron to assist in their documentation and restoration. Gilliéron and his son Émile, born in 1885 and generally known as "Gilliéron fils", would work for Evans at Knossos for the next three decades.[34] Evans constructed a gallery above the "Throne Room" to display copies of Gilliéron's work, replacing finds which had been removed for display at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum.[69] Gilliéron also began, from 1901, to produce and sell replicas of the finds from Knossos.[70] He offered versions reflecting the objects' state on discovery, as well as more extensively restored versions which purported to reproduce the objects as originally manufactured.[71] In the case of objects such as the Harvester Vase from Hagia Triada, this required imaginatively reconstructing pieces of the object which had been lost or destroyed prior to discovery.[71]

In 1907 Gilliéron was chosen by the Archaeological Society of Athens to produce watercolor copies of the painted funerary stelai from the Hellenistic city of Demetrias (Pagasai) in Thessaly. In the Society's excavations at the site, directed by Apostolos Arvanitopoulos, more than 700 tombstones of the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE, many with their polychrome decoration still well preserved, were found reused as building material in the fortifications of the city.[72] Their importance was immediately recognized: a new museum to house the finds was built in Volos, a program of conservation was begun, and Gilliéron was hired to make copies of some of the best preserved stelai in order to document their coloring while it was still fresh.[73] Between 1907 and 1913 he made several trips to the Volos and painted at least fourteen of the tombstones.[74] During the later trips he was accompanied by his son, who continued to work for Arvanitopoulos until 1917, although the archaeologist considered the son's work inferior to that of his father.[75] Chromolithographic reproductions of ten of the elder Gilliéron's watercolors appeared in Arvanitpoulos's publication of the excavations in 1928.[76] Gilliéron also made additional versions of some of the paintings, three of which were purchased by Robert for the archaeological museum at Halle.[77]

Gilliéron père was hired between 1910 and 1912 by the German team, led by Georg Karo, continuing Schliemann's excavations at Tiryns; he restored the so-called "Shield Frieze" fresco from over two hundred fragments found in the inner forecourt of the palace. In some of his restorations at Tiryns, such as that of a woman carrying an ivory pyxis, Gilliéron disguised the distinction between original and restored material, creating the illusion that the entire fresco was original when in fact much of it was compiled from parts of other figures in the same scene.[78] The two Gilliérons later worked with Karo on the publication of the finds from Schliemann's 1876 excavations of Grave Circle A at Mycenae, which Karo published between 1930 and 1933.[79]

Over time, Gilliéron transferred an increasing proportion of his work to his son, and renamed his business Gilliéron et fils ('Gilliéron and Son'). Gilliéron fils has been credited by the archaeological historian Joan Mertens with improving the commercial success of their joint studio, and with extending its clientele to include patrons in Cuba and the United States as well as in Europe. Between 1906 and 1933, the Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased almost seven hundred artworks from the Gilliérons.[80] The Gilliérons also worked on finds from Mycenae. Around 1906, Gilliéron père reproduced several of the objects from Grave Circle A, including the gold mask known as the "Mask of Agamemnon". Around 1918–1919, the Gilliérons replicated a painted stele discovered at Mycenae in 1893.[69]

Personal life and death

In his memoirs, de Chirico described Gilliéron as "a tall, robust man, with a thick white beard trimmed to a point".[81] Gerhart Rodenwaldt described his personality as "ingenious, passionate, clever, and humorous",[82] and Paul Wolters wrote that he was "a man well aware of his own worth, but without ever becoming arrogant".[83] His mother died five years after he was born, and two of his brothers also died early: his younger brother Gustave in 1866 while still a teenager, and his older brother, the classicist Alfred Gilliéron, of typhus in Macedonia in 1878.[84] His youngest brother, Jules Gilliéron, became a linguist at the École pratique des hautes études and co-authored the Atlas linguistique de la France.[85] Gilliéron married Joséphine Zoecchi, also a painter, in 1884.[86] They had five children, including Émile fils.[87] Gilliéron père died in Athens on 13 October 1924,[1] and was buried in the First Cemetery of Athens.[88]

Assessment

Mertens has written that Gilliéron's significance lay partly in being present at the unearthing of so many major archaeological discoveries, and being able to record their original colours before exposure to light and air damaged them. She also notes the size of Gilliéron's professional network and his ability to parlay that into financial opportunities – both of which she describes as "exceptional".[90]

Gilliéron's contemporaries praised his skill as a draughtsman, particularly the precision with which he reproduced the finest details of the works that copied, and his ability to recognize faint traces of original decoration on badly damaged artifacts. His friend and colleague Wolters wrote that "one could not wish for a more skilled and conscientious draughtsman as a collaborator. He loved ancient art, he admired the subtle delicacy of the brushstrokes and engraved lines, and tried with success to achieve the same level of accuracy. Of the archaeological problems of restoration he had a complete understanding; above all, he was the most helpful assistant in recovering and clarifying almost-vanished traces on severely destroyed originals, and he always made every effort to interpret them correctly."[91] Arvanitopoulos, for whom he produced watercolors of the painted funerary stelai from Demetrias, wrote that "the elder Gilliéron had an innate delicacy and elegance in the rendering of lines; he transmitted these qualities to the copies as well, so that many of them appear more graceful than the archetypes, without, however, departing from them in terms of the faithful rendering of even the smallest details." The purely artistic qualities of his watercolors have been admired more recently as well: Mertens describes the paintings of Acropolis sculpture in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum in New York as "tours de force of the watercolorist's art", and praises "his mastery of the media, both in the pencil drawing and in the application of color. Even with the use of technical aids to reproduce existing models or templates, the fluency of his execution over such large surfaces is exceptional, and, whether totally accurate or not, his sense of color in many areas is ravishing."[92] Wolters felt that many of these qualities could not be properly appreciated in the published reproductions of his works, because of the reduction in size and defects in printing.[48]

The archaeologists with whom he worked thought highly of Gillieron not just as an artist, but also as a collaborator who welcomed criticism and discussion. According to Rodenwaldt, Gilliéron believed that "a truly adequate copy could only be achieved through the constant collaboration of two personalities, an artist to execute the work and a critic to compare and correct it. He glady sought advice from scholars who seemed competent to him, and never felt entirely comfortable with work in which he had to do without such constant collaboration."[93] Wolters similarly observed that "he demanded sharp criticism from us and expressed open displeasure if a drawing was accepted sight unseen", because this suggested to him that the client did not take the work as seriously as he did.[48]

Influence of Gilliéron's work

MacGillivray has judged that Gilliéron produced "some of the most enduring watercolour reproductions of objects otherwise impossible to imagine because of their poor state of preservation".[23] Lapatin credits Gilliéron and his son second only to Evans in creating the popular image of Knossos and Minoan society.[94] The Gilliérons' prominent role in the reconstruction and publication of many of the most high-profile archaeological finds of their lifetime has led Mertens to conclude that "their images, in large measure, have defined our visual impressions of the great ancient cultures of the Greek world".[80] In particular, their colourful reconstructions of archaic sculptures, whose painted colours could not at the time be shown by photography, played a major role in the developing interest of the public and of academics such as Gisela Richter and Edward Robinson in ancient polychromy.[95]

Replicas produced by Gilliéron and his son were purchased and displayed widely by European and American museums, as they were considerably cheaper than genuine ancient artefacts. Their work was acquired by London's South Kensington Museum, New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, University College Dublin, the Winckelmann Institute of the Friedrich-Wilhelm University in Berlin, Harvard University, the University of Montpellier in France, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Ashmolean Museum of the University of Oxford and the Fitzwilliam Museum of the University of Cambridge.[55] The finds which were disseminated through their reconstructions have been cited as an influence on modernist writers, artists and intellectuals such as James Joyce, Sigmund Freud and Pablo Picasso.[69]

Criticism

Gilliéron's reconstructions often changed as his and his employers' assessments of the material evolved: a fresco at Knossos that he originally reconstructed as a young woman, labelled "Ariadne" by Evans after the mythical Cretan princess, became a figure of a male adolescent, described by the British archaeologist J. L. Myres as having "an European and almost classically Greek profile".[96] When the English writer Evelyn Waugh visited Knossos in 1929, he wrote that it was impossible to gain an appreciation of Minoan painting there, since original fragments of fresco were crowded out by modern restorations, and judged that Evans and Gilliéron had "tempered their zeal for reconstruction with a predilection for the covers of Vogue".[97] In 1969, the archaeologist Leonard Robert Palmer wrote a guide-book to the site of Knossos in which he described the "Ladies in Blue" fresco as "a spirited composition ... by M. Gilliéron".[98] Gilliéron may also have invented the scalloped pattern around the edge of the "Bull-Leapers Fresco" from Knossos, for which no ancient evidence has survived.[69] Gilliéron often consciously blurred the distinction between original material and his own restorations, both at Tiryns and at Knossos, where he placed some of his reconstructions directly onto the ancient walls, surrounding the original fragments.[99] In some cases, as with the "Blue Boy" fresco, Gilliéron's reconstruction has been shown to be incorrect: Gilliéron reconstructed the image with a figure of a boy, but further investigation showed that it was originally a monkey.[100]

Referring to the Gilliérons' practice of combining fragments later evaluated to have come from discrete images, a modern study has concluded that they "created a decorative programme which, as it currently stands, never existed".[101] Gilliéron's reconstruction of the so-called "Priest-King Fresco", which he developed from 1905 onwards,[102] has been particularly challenged: the fresco was reconstructed from fragments which both Evans and Gilliéron initially believed to belong to different figures.[103] The reconstruction was debated from the time of its publication in the 1920s.[104] Between 1970 and 1990, the physician Jean Coulomb and the archaeologist Wolf-Dietrich Niemeier separately argued that the fragments did indeed belong to separate figures:[105] Coulomb argued that the figure's torso belonged to a boxer,[106] while Niemeier considered that the crown was more likely to belong to a female figure, either a sphinx or a goddess, in line with depictions of similar crowns in other Minoan paintings.[107] It is also uncertain whether the figure's skin was originally coloured red, which would be typical of male figures in Minoan art, or white, which would be more typical of female figures.[105]

Accusations of archaeological criminality

The Gilliérons have been accused of facilitating or participating in the creating and distribution of forged antiquities.[108] The archaeologist Leonard Woolley, who visited Crete in 1923–1924, was present at a police raid on a workshop where local Cretan craftsmen produced forgeries of Minoan snake goddess figurines, and wrote that the forgers were working for Gilliéron.[109] The historian Cathy Gere has called Gilliéron "almost certainly an important link in the chain between the forgers and the museums and dealers of Europe and America".[110] While working with the Gilliérons on the Grave Circle A material, Karo came to suspect them of illicit activities.[111] The archaeological historian Kenneth Lapatin has suggested that Gilliéron may have been the pseudonymous "Mr. Jones" from whom the collector Richard Berry Seager reported receiving the "Boston Goddess", a snake goddess figurine generally considered a forgery, in 1914;[112] Gilleron may have offered the same object, or a similar forgery known as the "Baltimore Goddess", to Karo in the same year.[113] Lapatin suggests that a remark of Karo's about "goldsmiths working part-time as forgers" may have been a veiled reference to the Gilliérons.[109]

Selected restorations and replicas

-

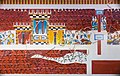

The "Grandstand Fresco" from Knossos, restored by Gilliéron in 1909.[114]

-

The "Blue Boy" fresco from Knossos, erroneously restored by Gilliéron with a boy instead of a monkey[100]

-

Reproduction of the "Shield Frieze" at Tiryns, made by Gilliéron before 1912[116]

-

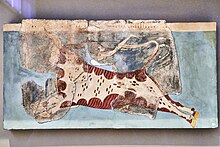

The "Bull-Leaping" or "Toreador" fresco from Knossos[117]

-

Cast of kore 674 from the Acropolis of Athens, painted by Gilléron fils after drawings made by his father at the time of discovery.[118]

Footnotes

Explanatory notes

References

- ^ a b c d Mitsopoulou & Polychronopoulou 2019, p. 726.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2024a, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Greppin 1889–1890, pp. 234–235; Mitsopoulou 2021b, pp. 35–36; Mitsopoulou 2024a, pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b Mitsopoulou 2024a, p. 56.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2021b, p. 36.

- ^ Rodenwaldt 1925, col. 358.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2021b, p. 36; Mitsopoulou 2024a, p. 56.

- ^ Mitsopoulou & Polychronopoulou 2019, p. 726; Mitsopoulou 2021b, p. 36.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2024a, p. 56; Mitsopoulou 2024b.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2021a, pp. 265–267.

- ^ Four uncredited lithographs based on Emile's painted landscapes and character sketches appeared in the description of the voyage published by his brother in 1877: Gilliéron 1877; Mitsopoulou 2021a, pp. 264–267; Mitsopoulou 2024a, pp. 54–56.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2024a, pp. 56–57; Mitsopoulou & Polychronopoulou 2019, p. 726.

- ^ Mitsopoulou & Polychronopoulou 2019, p. 726; Loreti 2014, p. 195 (for Kolonaki).

- ^ Mitsopoulou & Polychronopoulou 2019, p. 726; Mitsopoulou 2024a, p. 56.

- ^ Nicholas of Greece 1926, p. 19; Mitsopoulou 2021a, p. 268.

- ^ Hemingway 2011; Gere 2009, p. 99 (for the date).

- ^ Loreti 2014, p. 196.

- ^ Rodenwaldt 1925, col. 359; Wolters 1925, col. ix.

- ^ Rodenwaldt 1925, col. 359; quoted by Mitsopoulou 2021b, p. 36.

- ^ Wolters 1925, col. xi; Mitsopoulou 2021b, p. 37.

- ^ Wolters 1925, cols. ix–x; Rodenwaldt 1925, cols. 359–360; Sturgis 1890, pp. 542–543.

- ^ Mertens 2019, p. 9; Conte 2019, p. 29; MacGillivray 2000, p. 186.

- ^ a b c MacGillivray 2000, p. 186.

- ^ Wolters 1925, col. ix.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2021b, p. 42.

- ^ MacGillivray 2000, p. 186; Schliemann's monograph is Schliemann 1885.

- ^ Wolters 1925, cols. x–xi; Mitsopoulou 2021b, pp. 39, 42–43.

- ^ Wolters 1925, pp. viii, xxxii.

- ^ Sturgis 1890, pp. 543–543; Wolters 1925, col. x; Mertens 2019, pp. 7, 13–19.

- ^ Robinson 1891, pp. 12–13, 15; Mertens 2019, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Tolles 2003, p. 74.

- ^ Mertens 2019; Conte 2019. Mertens (p. 8) gives the number of objects as "almost seven hundred".

- ^ Conte 2019, pp. 27–29.

- ^ a b c Mertens 2019, p. 6.

- ^ MacGillivray 2000, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2021b, pp. 42–45.

- ^ Stais 1893; Mitsopoulou 2024c, p. 85.

- ^ Sotiriadis 1903, col. 72, pls. 2–6; Kawerau & Sotiriadis 1908, p. 3, pls. 50–52; Mitsopoulou 2021b, p. 42.

- ^ Lambros 1881, pp. 31–32; Dellaporta 2021. Twelve of Gilliéron's reproductions are preserved in the collection of the Byzantine and Christian Museum in Athens.

- ^ Nicholas of Greece 1926, p. 19; Mitsopoulou 2021b, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Robert 1895, p. 1; Mitsopoulou 2021b, pp. 46–48; Ehrhardt et al. 2021, p. 73.

- ^ Ehrhardt et al. 2021, pp. 73–85.

- ^ Robert 1895, p. 1; Ehrhardt et al. 2021, p. 73.

- ^ Ehrhardt et al. 2021, p. 73.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2021b, p. 48.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2021b, pp. 48–52; Ehrhardt et al. 2021, p. 87.

- ^ Breccia 1909, p. 383.

- ^ a b c Wolters 1925, col. x.

- ^ Rodenwaldt 1925, col. 360.

- ^ Mitsopoulou & Polychronopoulou 2019, p. 727; Davis 1974, p. 472 (for the cups' discovery).

- ^ Mitsopoulou & Polychronopoulou 2019, p. 727; Mitsopoulou 2021a, pp. 36.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2021a, pp. 285–289.

- ^ Wolters 1911; Mitsopoulou & Polychronopoulou 2019, p. 728; Mitsopoulou 2021b, p. 44.

- ^ Mitsopoulou & Polychronopoulou 2019, p. 728.

- ^ a b c Lapatin 2002, p. 139.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2021a, p. 273, 280–281; Conte 2019, p. 30; "Sog. Kore mit den Sphinxaugen" [So-Called Kore with the Sphinx Eyes] (in German). Museum für Abgüsse Klassischer Bildwerke München. Retrieved 2023-12-31..

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2024d.

- ^ Marmaridou 2024, pp. 170–172.

- ^ Marmaridou 2024, pp. 170–171, 174–175; Mitsopoulou 2024h.

- ^ Marmaridou 2024, p. 171.

- ^ Marmaridou 2024, pp. 171–172, 176–177; Mitsopoulou 2024h.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2024d, pp. 114–116.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2024e.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2024i.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2024f; Mitsopoulou 2024g.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2024j.

- ^ Galanakis, Tsitsa & Günkel-Maschek 2017, p. 48.

- ^ Quoted in Lapatin 2002, p. 121.

- ^ a b c d e f Hemingway 2011.

- ^ Lapatin 2002, p. 136.

- ^ a b Lapatin 2002, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Stamatopoulou 2016, pp. 406–408.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2021b, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2021b, pp. 52–55.

- ^ harvnb

- ^ Arvanitopoulos 1928.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2021b, pp. 55–61.

- ^ Hemingway 2011; Matz 1964, p. 639 (for Karo's role).

- ^ Marinatos 2020, pp. 76–77. Karo's publication is Karo 1930–1933.

- ^ a b Mertens 2019, p. 8.

- ^ de Chirico 1971, p. 34; quoted in Gere 2009, p. 99.

- ^ Rodenwaldt 1925, col. 361 ("originelle, leidenschaftliche, geistreiche und humorvolle").

- ^ Wolters 1925, col. xi.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2021b, pp. 34, 36; Mitsopoulou 2024a, p. 54.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2024a, p. 55.

- ^ Mertens 2019, p. 6; Mitsopoulou 2021b, p. 34.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2021b, p. 34.

- ^ Mitsopoulou 2021b, p. 33.

- ^ Rodenwaldt 1925, cols. 359–360.

- ^ Mertens 2019, p. 7.

- ^ Wolters 1925, cols. ix–x.

- ^ Mertens 2019, pp. 9, 24.

- ^ Rodenwaldt 1925, col. 361.

- ^ Lapatin 2002, p. 133.

- ^ Mertens 2019, p. 9.

- ^ MacGillivray 2000, p. 194; Myres 1901, p. 5.

- ^ Waugh 1930, republished as Waugh 1946, pp. 51–52, quoted in MacGillivray 2000, p. 194.

- ^ Palmer 1969, p. 128, quoted in Gere 2009, p. 222.

- ^ Hemingway 2011; Lapatin 2002, p. 131.

- ^ a b Lapatin 2002, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Galanakis, Tsitsa & Günkel-Maschek 2017, p. 50.

- ^ Gere 2009, p. 121.

- ^ MacGillivray 2000, p. 204.

- ^ See, for example, Glotz 2013, p. 398.

- ^ a b Shaw 2004, p. 65.

- ^ Shaw 2004, p. 70.

- ^ Shaw 2004, pp. 65, 70.

- ^ Cohon 2010, pp. 202–203.

- ^ a b Lapatin 2002, p. 171.

- ^ Gere 2009, p. 128.

- ^ Marinatos 2020, p. 76.

- ^ Lapatin 2002, pp. 144–150.

- ^ Lapatin 2002, pp. 142–143; Cooper 2020, p. 90.

- ^ MacGillivray 2000, p. 255.

- ^ MacGillivray 2000, p. 243.

- ^ Richter 1912, p. 117.

- ^ Lapatin 2002, p. 112.

- ^ Richter 1924.

Bibliography

- Arvanitopoulos, Apostolos (1928). Γραπταὶ στῆλαι Δημητριάδος–Παγασῶν [Painted Stelai of Demetrias–Pagasai]. Library of the Archaeological Society of Athens 23 (in Greek). Athens. doi:10.11588/diglit.4899.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Breccia, Evaristo (1909). "Bolletino bibliografica". Bulletin de la Société Archéologique d'Alexandrie (in Italian). 11: 375–396.

- de Chirico, Giorgio (1971) [1962]. The Memoirs of Georgio de Chirico. Translated by Crosland, Margaret. Coral Gables: University of Miami Press. ISBN 0-87024-125-7. Retrieved 2024-01-17 – via Internet Archive.

- Cohon, Robert (2010). "Forgeries, Artistic". In Gagarin, Michael (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 201–205. ISBN 978-0-19-517072-6. Retrieved 2024-02-01 – via Oxford Reference.

- Conte, Lisa (2019). "Gilliéron's Art and the Conservator's Challenge". In Mertens, Joan R. & Conte, Lisa (eds.). Watercolors of the Acropolis: Émile Gilliéron in Athens (PDF). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 27–43. ISBN 978-1-58839-670-9.

- Cooper, Kate L. (2020). "Biography of the Bull-Leaper: A 'Minoan' Figurine and Collecting Antiquity". In Cooper, Kate L. (ed.). New Approaches to Ancient Material Culture in the Greek and Roman World: 21st-Century Methods and Classical Antiquity. Leiden: Brill. pp. 79–102. ISBN 978-90-04-44075-3. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- Davis, Ellen N. (1974). "The Vapheio Cups: One Minoan and One Mycenaean?". The Art Bulletin. 56 (4): 472–487. doi:10.2307/3049295. JSTOR 3049295.

- Dellaporta, Katerina (2021). "Émile Gilliéron père, Saint Nilos". In Martinez, Jean-Luc (ed.). Paris–Athènes: Naissance de la Grèce moderne, 1675–1919 [Paris–Athens: The Birth of Modern Greece, 1675–1919] (in French). Paris: Hazan. pp. 444–445. ISBN 9782754112123.

- Ehrhardt, Wolfgang; Lehmann, Stephan; Löhr, Henryk; Mitsopoulou, Christina (2021). "Der erhaltene Bestand der Aquarellkopien antiker Wand- und Marmorbilder". In Lehmann, Stephan (ed.). Die Aquarellkopien antiker Wand- und Marmorbilder im Archäologischen Museum von Émile Gilliéron u. a. Kataloge und Schriften des archäologischen Museums der Martin-Luther-Universität. Dresden: Sandstein Verlag. pp. 33–65. ISBN 9783954986187.

- Galanakis, Yannis; Tsitsa, Efi & Günkel-Maschek, Ute (2017). "The Power of Images: Re-Examining the Wall Paintings from the Throne Room at Knossos". Annual of the British School at Athens. 112: 47–98. doi:10.1017/S0068245417000065.

- Gere, Cathy (2009). Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/9780226289557 (inactive 2024-11-02). ISBN 978-0-226-28954-0.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Gilliéron, Alfred (1877). Grèce et Turkie: Notes de voyage [Greece and Turkey: Travel Notes] (in French). Paris: Sandoz et Fischbacher.

- Glotz, Gustave (2013) [1925]. The Aegean Civilization. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-19530-3. Retrieved 2024-01-17 – via Internet Archive.

- Greppin, Edouard (1889–1890). "Victor Gilliéron". Verhandlungen der Schweizerischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft. 73: 234–238.

- Hemingway, Séan (2011-05-07). "Historic Images of the Greek Bronze Age". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 2016-03-17. Retrieved 2023-10-18.

- Karo, Georg (1930–1933). Die Schachtgräber von Mykenai [The Shaft Graves of Mycenae] (in German). Munich: F. Bruckmann. OCLC 4322356. Retrieved 2024-01-16 – via Heidelberg University Library.

- Kawerau, Georg; Sotiriadis, Georgios (1908). "Der Apollotempel zu Thermos" [The Temple of Apollo at Thermos]. Antike Denkmäler (in German). Vol. II. 1902–1908: pages 1–8, pls. 49–53. doi:10.11588/diglit.655.

- Lambros, Spyridon (1881). Ein Besuch auf dem Berge Athos [A Visit to Mount Athos] (in German). Translated by Rickenbach, P. Heinrich von. Würzburg: Leo Woerl.

- Lapatin, Kenneth D. S. (2002). Mysteries of the Snake Goddess: Art, Desire and the Forging of History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-14475-7. Retrieved 2024-01-01 – via Internet Archive.

- Loreti, Silvia (2014). "The Avant-Garde Classicism of Giorgio de Chirico". In Kouneni, Lena (ed.). The Legacy of Antiquity: New Perspectives in the Reception of the Classical World. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 184–215. ISBN 978-1-4438-6774-0.

- MacGillivray, Joseph Alexander (2000). Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 0-8090-3035-7.

- Marinatos, Nanno (2020). Sir Arthur Evans and Minoan Crete. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-350-19735-0.

- Marmaridou, Constantina (2024). "'Un timbre est une oeuvre d'art en miniature'" [A stamp is a work of art in miniature]. In Mitsopoulou, Christina; Farnoux, Alexandre; Jeammet, Violaine (eds.). L'Olympisme: Une invention moderne, un héritage antique [Olympianism: A Modern Invention, an Ancient Heritage] (in French). Paris: Hazan. pp. 169–177. ISBN 9782754113830.

- Matz, Friedrich (September 1964). "Georg Karo". Gnomon. 36 (6): 637–640. JSTOR 27683484.

- Mertens, Joan R. (2019). "Watercolors of the Acropolis: Émile Gilliéron in Athens". In Mertens, Joan R. & Conte, Lisa (eds.). Watercolors of the Acropolis: Émile Gilliéron in Athens (PDF). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-1-58839-670-9.

- Mitsopoulou, Christina (2021a). "L'atelier des Gilliéron: Une fabrique de l'imagerie nationale grecque" [The atelier of Gilliéron: A workshop for Greek national imagery]. In Martinez, Jean-Luc (ed.). Paris–Athènes: Naissance de la Grèce moderne, 1675–1919 [Paris–Athens: The Birth of Modern Greece, 1675–1919] (in French). Paris: Hazan. pp. 262–289. ISBN 9782754112123.

- Mitsopoulou, Christina (2021b). "Der Künstler Émile Gilliéron und seine Werke: Zur Vermittlung archäologischer Forschungsergebnisse an den Beispielen der Aquarellkopien aus Pompeji, Herculaneum, und Demetrias". In Lehmann, Stephan (ed.). Die Aquarellkopien antiker Wand- und Marmorbilder im Archäologischen Museum von Émile Gilliéron u. a. Kataloge und Schriften des archäologischen Museums der Martin-Luther-Universität (in German). Dresden: Sandstein Verlag. pp. 33–65. ISBN 9783954986187.

- Mitsopoulou, Christina (2024a). "Gilliéron et son entourage" [Gilliéron and his entourage]. In Mitsopoulou, Christina; Farnoux, Alexandre; Jeammet, Violaine (eds.). L'Olympisme: Une invention moderne, un héritage antique [Olympianism: A Modern Invention, an Ancient Heritage] (in French). Paris: Hazan. pp. 52–61. ISBN 9782754113830.

- Mitsopoulou, Christina (2024b). "Gilliéron étudiant à l'École des Beaux-Arts et au Louvre" [Gilliéron's studies at the École des Beaux-Arts and at the Louvre]. In Mitsopoulou, Christina; Farnoux, Alexandre; Jeammet, Violaine (eds.). L'Olympisme: Une invention moderne, un héritage antique [Olympianism: A Modern Invention, an Ancient Heritage] (in French). Paris: Hazan. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9782754113830.

- Mitsopoulou, Christina (2024c). "Marathon et l'Olympisme moderne" [Marathon and modern Olympianism]. In Mitsopoulou, Christina; Farnoux, Alexandre; Jeammet, Violaine (eds.). L'Olympisme: Une invention moderne, un héritage antique [Olympianism: A Modern Invention, an Ancient Heritage] (in French). Paris: Hazan. pp. 80–85. ISBN 9782754113830.

- Mitsopoulou, Christina (2024d). "L'atelier olympique de Gilliéron" [Gilliéron's Olympic Atelier]. In Mitsopoulou, Christina; Farnoux, Alexandre; Jeammet, Violaine (eds.). L'Olympisme: Une invention moderne, un héritage antique [Olympianism: A Modern Invention, an Ancient Heritage] (in French). Paris: Hazan. pp. 110–121. ISBN 9782754113830.

- Mitsopoulou, Christina (2024e). "'Affiche' des premiers jeux Olympiques d'Athènes 1896" ['Poster' of the First Olympic Games in Athens, 1896]. In Mitsopoulou, Christina; Farnoux, Alexandre; Jeammet, Violaine (eds.). L'Olympisme: Une invention moderne, un héritage antique [Olympianism: A Modern Invention, an Ancient Heritage] (in French). Paris: Hazan. pp. 122–129. ISBN 9782754113830.

- Mitsopoulou, Christina (2024f). "La table des trophées, Mésolympiade 1906" [The Table of Trophies, Intercalated Games 1906]. In Mitsopoulou, Christina; Farnoux, Alexandre; Jeammet, Violaine (eds.). L'Olympisme: Une invention moderne, un héritage antique [Olympianism: A Modern Invention, an Ancient Heritage] (in French). Paris: Hazan. pp. 144–153. ISBN 9782754113830.

- Mitsopoulou, Christina (2024g). "Canthare du sanctuaire du Kabirion à Thèbes" [Kantharos from the sanctuary of the Kabeirion at Thebes]. In Mitsopoulou, Christina; Farnoux, Alexandre; Jeammet, Violaine (eds.). L'Olympisme: Une invention moderne, un héritage antique [Olympianism: A Modern Invention, an Ancient Heritage] (in French). Paris: Hazan. pp. 156–159. ISBN 9782754113830.

- Mitsopoulou, Christina (2024h). "Iconographie des timbres commémoratifs des jeux Olympiques de 1896 et 1906" [Iconography of the Commemorative Stamps for the Olympic Games in 1896 and 1906]. In Mitsopoulou, Christina; Farnoux, Alexandre; Jeammet, Violaine (eds.). L'Olympisme: Une invention moderne, un héritage antique [Olympianism: A Modern Invention, an Ancient Heritage] (in French). Paris: Hazan. pp. 178–188. ISBN 9782754113830.

- Mitsopoulou, Christina (2024i). "Dix cartes postales pour la Mésolympiade de 1906" [Ten Postcards for the Intercalated Games of 1906]. In Mitsopoulou, Christina; Farnoux, Alexandre; Jeammet, Violaine (eds.). L'Olympisme: Une invention moderne, un héritage antique [Olympianism: A Modern Invention, an Ancient Heritage] (in French). Paris: Hazan. pp. 189–191. ISBN 9782754113830.

- Mitsopoulou, Christina (2024j). "Cinq médaillons en plâtre servant de modèles (modelli) pour le décor des trophées du pentathle" [Five Plaster Medallions Serving as Models (Modelli) for the Decoration of the Pentathlon Trophies]. In Mitsopoulou, Christina; Farnoux, Alexandre; Jeammet, Violaine (eds.). L'Olympisme: Une invention moderne, un héritage antique [Olympianism: A Modern Invention, an Ancient Heritage] (in French). Paris: Hazan. pp. 244–252. ISBN 9782754113830.

- Mitsopoulou, Christina & Polychronopoulou, Olga (2019). "The Archive and Atelier of the Gilliéron Artists: Three Generations, a Century (1870s–1980)". In Borgna, Elisabetta; Caloi, Ilaria; Carinci, Filippo & Laffineur, Robert (eds.). MHMH/MNEME: Past and Memory in the Aegean Bronze Age. Aegeum. Vol. 43. Leuven: Peeters. pp. 725–729. ISBN 978-90-429-3903-5. Retrieved 2023-10-18.

- Myres, John L. (1901). "The Cretan Exploration Fund: An Abstract of the Preliminary Report of the First Season's Excavations". Man. 1: 4–7. doi:10.2307/2840775. JSTOR 2840775. Retrieved 2024-01-16 – via Internet Archive.

- Nicholas of Greece (1926). My Fifty Years. London: Hutchinson and Co. – via Hathi Trust.

- Palmer, Leonard Robert (1969). A New Guide to the Palace of Knossos. New York: Frederick A. Praeger. ISBN 978-0-571-08727-3. SBN 571-08727-2. Retrieved 2024-02-01 – via Internet Archive.

- Richter, Gisela (1912). "Reproductions of Minoan Frescoes". Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. 7 (6): 116–117. doi:10.2307/3252678. JSTOR 3252678.

- Richter, Gisela (1924). "An Exhibition of Greek Casts". Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. 19 (7): 164–165.

- Robert, Carl (1895). Votivgemälde eines Apobaten. Hallisches Winckelmannsprogramm 19. Halle: Max Niemeyer – via Hathi Trust.

- Robinson, Edward (1891). "From the Report of the Curator of Classical Antiquities". Annual Report of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. 16: 10–17.

- Rodenwaldt, Gerhart (1925). "Archäologische Gesellschaft zu Berlin. Sitzung vom 4. November 1924". Archäologischer Anzeiger. 1923–1924. cols. 358–361.

- Schliemann, Heinrich (1885). Tiryns: The Prehistoric Palace of the Kings of Tiryns. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. OCLC 1198337. Retrieved 2024-01-03 – via Internet Archive.

- Shaw, Maria C. (2004). "The 'Priest-King' Fresco from Knossos: Man, Woman, Priest, King, or Someone Else?". In Chapin, Anne P. (ed.). ΧΑΡΙΣ: Essays in Honor of Sara A. Immerwahr. Hesperia Supplements. Vol. 33. Athens: American School of Classical Studies at Athens. pp. 65–84. ISBN 0-8766-1533-7. JSTOR 1354063.

- Sotiriadis, Georgios (1903). "Ἀνασκαφαὶ ἐν Θέρμῳ· Β'. Αἱ μέτοπαι τοῦ ναοῦ τοῦ Θερμίου Ἀπόλλωνος" [The Metopes of the Temple of Apollo Thermios] (PDF). Ἀρχαιολογικὴ Ἐφημερίς (in Greek). 1903. cols. 71–96.

- Stais, Valerios (1893). "Ὁ ἐν Μαραθῶνι τύμβος" [The tomb at Marathon]. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung (in Greek). 18: 46–63. doi:10.11588/diglit.37662.10.

- Stamatopoulou, Maria (2016). "The Banquet Motif on the Funerary Stelai from Demetrias". In Draycott, Catherine M.; Stamatopoulou, Maria (eds.). Dining And Death: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on the 'Funerary Banquet' in Ancient Art, Burial, and Belief. Colloquia Antiqua 16. Leuven: Peeters. pp. 405–479. ISBN 9789042932517.

- Sturgis, Russell (September 1890). "Recent Discoveries of Painted Greek Sculpture" (PDF). Harper's New Monthly Magazine. 81: 538–550.

- Tolles, Thayer (2003). "'In a Class by Themselves': Polychrome Portraits by Herbert Adams". In Tolles, Thayer (ed.). Perspectives on American Sculpture before 1925. Metropolitan Museum of Art Symposia. New York: Yale University Press. pp. 64–81. ISBN 9781588391056 – via Internet Archive.

- Vuillermet, Charles (1905). "Gilliéron, Emile". In Brun, Carl (ed.). Schweizerisches Künstler-lexikon. Vol. I. Frauenfeld: Huber and Co. p. 578 – via Internet Archive.

- Waugh, Evelyn (1930). Labels. London: Duckworth. OCLC 458880564.

- Waugh, Evelyn (1946). When the Going Was Good. London: Duckworth. OCLC 170209.

- Wolters, Paul (1911). Galvanoplastische Nachbildungen mykenischer und kretischer (minoischer) Altertümer von E. Gilliéron & fils [Galvanoplastic Copies of Mycenaean and Cretan (Minoan) Antiquities by E. Gilliéron and Son] (in German, English, and French). Stuttgart: Kast und Ehinger – via Hathi Trust.

- Wolters, Paul (1925). "Vorwort". Die antiken Vasen von der Akropolis zu Athen. By Graef, Botho; Langlotz, Ernst (in German). Vol. I. Berlin: De Gruyter. cols. i–xxxvi.

![Part of Gilliéron's restoration of a female figure, carrying a pyxis, from Tiryns[69]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/92/Female_figure_from_the_Mycenaean_frescoes_of_Tiryns_at_the_National_Archaeological_Museum_of_Athens_%2826-10-2021%29.jpg/113px-Female_figure_from_the_Mycenaean_frescoes_of_Tiryns_at_the_National_Archaeological_Museum_of_Athens_%2826-10-2021%29.jpg)

![The "Bull-Leaping" or "Toreador" fresco from Knossos[117]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/13/Bull_leaping_fresco%2C_Knossos%2C_1600-1450_BC%2C_AMH%2C_145129.jpg/120px-Bull_leaping_fresco%2C_Knossos%2C_1600-1450_BC%2C_AMH%2C_145129.jpg)