1943 Cairo Declaration

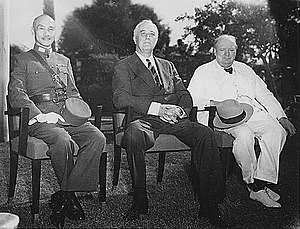

The Cairo Declaration (Traditional Chinese: 《開羅宣言》) was the outcome of the Cairo Conference in Cairo, Egypt, on 27 November 1943. President Franklin Roosevelt of the United States, Prime Minister Winston Churchill of the United Kingdom, and Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek of the Republic of China were present. The declaration developed ideas from the 1941 Atlantic Charter, which was issued by the Allies of World War II to set goals for the post-war order. The Cairo Communiqué was broadcast through radio on 1 December 1943.[1]

Text

"The several military missions have agreed upon future military operations against Japan. The Three Great Allies expressed their resolve to bring unrelenting pressure against their brutal enemies by sea, land, and air. This pressure is already rising."

"The Three Great Allies are fighting this war to restrain and punish the aggression of Japan. They covet no gain for themselves and have no thought of territorial expansion. It is their purpose that Japan shall be stripped of all the islands in the Pacific which she has seized or occupied since the beginning of the first World War in 1914, and that all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa, and The Pescadores, shall be restored to the Republic of China. Japan will also be expelled from all other territories which she has taken by violence and greed. The aforesaid three great powers, mindful of the enslavement of the people of Korea, are determined that in due course Korea shall become free and independent."

"With these objects in view the three Allies, in harmony with those of the United Nations at war with Japan, will continue to persevere in the serious and prolonged operations necessary to procure the unconditional surrender of Japan."[2]

Controversy as to Taiwan

The Cairo Declaration is cited in Clause Eight (8) of the Potsdam Declaration, which is referred to by the Japanese Instrument of Surrender.

Both the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China have cited the Cairo Declaration as one of the bases for the One-China Principle that Taiwan and Penghu are part of Republic of China.[3][4] However, the major political parties in Taiwan have not taken the same position on this matter,[5] and various historians in Taiwan have said that the Cairo Declaration was not binding.[6]

The government of the United States considers the declaration a statement of intention and never formally implemented.[7] In November 1950, the United States Department of State said that no formal act restoring sovereignty over Formosa and the Pescadores to China had yet occurred;[8]

In February 1955, Winston Churchill stated that the Cairo Declaration "contained merely a statement of common purpose" and the question of Taiwan's future sovereignty was left undetermined by the Japanese peace treaty.[9][10] British officials reiterated this viewpoint in May 1955.[11]

In March 1961, then-Japanese Minister for Foreign Affairs responded that:

It was specified in Potsdam Proclamation that articles in Cairo Declaration should be carried out, and in accordance with Japanese Instrument of Surrender we announced that we would comply with Potsdam Proclamation. However, the so-called Japanese Instrument of Surrender possesses the nature of armistice and does not possess the nature of territorial disposition.[12]

On the other hand, then-ROC president Ma Ying-jeou cited a series of instruments beginning with the Cairo Declaration and stated in 2014:[13]

The implementation of the legal obligation to return Taiwan and its appertaining islands (including the Diaoyutai Islands) to the ROC was first stipulated in the Cairo Declaration, and later reaffirmed in the Potsdam Proclamation, the Japanese Instrument of Surrender, the San Francisco Peace Treaty, and the Treaty of Peace between the Republic of China and Japan. The Cairo Declaration is therefore a legally binding instrument with treaty status.

Controversy as to Korea

Many prominent Koreans in the Korean independence movement, including Kim Ku and Syngman Rhee, were initially delighted by the declaration, but later noticed and became infuriated by the phrase "in due course". They took it to be an affirmation of Allied intent to place Korea into a trusteeship, rather than granting it immediate independence. There was significant concern that the trusteeship could be indefinite or last decades, making Korea functionally again a colony under a great power.[14][15]

The phrase "in due course" was not present in the first draft; it originally read "at the earliest possible moment after the downfall of Japan". The US suggested "at the proper moment", and finally the British "in due time". Exact motivations for these changes are unclear.[14]

See also

- Cairo Conference 1943

- Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945)

- Potsdam Declaration (July 1945)

- General Order No. 1 (August 1945)

- Japanese Instrument of Surrender (September 1945)

- Korea Retrocession (August 1945)

- Taiwan Retrocession (October 1945)

- Treaty of San Francisco (1951)

- Cairo Declaration (film)

References

- ^ "Cairo Communiquè, December 1, 1943". Japan National Diet Library. December 1, 1943.

- ^ Text of Cairo Declaration, Government of Japan website

- ^ Zhao, Suisheng (2022). The Dragon Roars Back: Transformational Leaders and Dynamics of Chinese Foreign Policy. Stanford University Press. p. 34. doi:10.1515/9781503634152. ISBN 978-1-5036-3415-2.

- ^ "MOFA reaffirms ROC sovereignty over Taiwan, Penghu". 5 September 2011.

- ^ Hsiao-kuang, Shih and Chin, Jonathan. "KMT pans DPP for disputing retrocession legitimacy", Taipei Times (October 26, 2017): "The 1943 Cairo Declaration should be considered legally binding, former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) and former vice president Lien Chan (連戰) said at a rally held by the KMT in Taipei to mark the 72nd Retrocession Day …. Those who dispute the validity of the Cairo Declaration should be dismissed as amateurs, Ma said, naming former vice president Annette Lu (呂秀蓮) of the DPP and former minister of education Tu Cheng-sheng (杜正勝), an Academia Sinica historian."

- ^ Wang, Chris. "Cairo Declaration as legal basis incorrect: advocates", Taipei Times (December 2, 2013): "Since [President] Ma took the same position on the declaration as Beijing, which cited it as the legal basis for Taiwan's return to China, he is risking two important issues, said Vincent Chen (陳文賢), a professor at National Chengchi University's Graduate Institute of Taiwan History…. '[Ma's] adherence to the one-China framework could, in the long run, create a false perception among the international community that Taipei and Beijing would follow the post-World War II unification models of Vietnam and Germany and unify in the future,' he said."

- ^ Monte R. Bullard (2008). Strait Talk: Avoiding a Nuclear War Between the US and China over Taiwan (PDF). Monterey, CA: James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS). p. 294. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-13.

- ^ United States Dept of State (11 Nov 1950). "Sec. of State (Acheson) to Sec. of Defense (Marshall)". Foreign relations of the United States. Washington DC: US GPO: 554–5. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ Drew Middleton (February 2, 1955). "Cairo Formosa Declaration Out of Date, Says Churchill". New York Times. United States. Archived from the original on 2022-03-17. Retrieved 2017-07-31.

- ^ "FORMOSA (SITUATION)". hansard.millbanksystems.com (© UK Parliament). 1955-02-01. Archived from the original on 2021-01-07. Retrieved 2015-08-15.

- ^ "Far East (Formosa and the Pescadores)", Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), 4 May 1955, archived from the original on 2017-10-18, retrieved 2015-12-09

- ^ 参議院会議録情報 第038回国会 予算委員会 第15号. 昭和36年3月15日. p. 19. . 小坂善太郎:「ポツダム宣言には、カイロ宣言の条項は履行せらるべしということが書いてある。そうしてわれわれは降伏文書によって、ポツダム宣言の受諾を宣言したのであります。しかし、これは降伏文書というものは、休戦協定の性格を有するものでありまして、領土的処理を行ない得ない性質のものであるということを申し上げたのであります。」

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs clarifies legally binding status of Cairo Declaration". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan). January 21, 2014. Archived from the original on Dec 26, 2023.

- ^ a b Caprio, Mark E. (2022). "(Mis)-Interpretations of the 1943 Cairo Conference: The Cairo Communiqué and Its Legacy among Koreans During and After World War II". International Journal of Korean History. 27 (1): 137–176. doi:10.22372/ijkh.2022.27.1.137. S2CID 247312286.

- ^ "孫世一의 비교 評傳 (67) 한국 민족주의의 두 類型 - 李承晩과 金九". monthly.chosun.com (in Korean). 2007-10-07. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

External links

- Text of the Cairo Communiqué in the Japanese National Diet Library

- FRUS1943 Cairo Conference University of Wisconsin Digital Collection

- Cairo Declaration Department of State

- Cairo Declaration Yale University

- Cairo Formosa Declaration Out of Date, Says Churchill; CHURCHILL CALLS PLEDGE OUTDATED By Drew Middleton special To the New York Times. Feb. 2, 1955

- Cairo Formosa Declaration Out of Date, Says Churchill; CHURCHILL CALLS PLEDGE OUTDATED By Drew Middleton special To the New York Times. Feb. 2, 1955 (This source has a picture of the full newspaper article, including the continuation on page 4 of the original paper, which the nytimes.com source wouldn't show without membership)