1977 Dutch train hostage crisis

| 1977 Dutch train hijacking | |

|---|---|

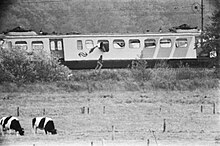

Hijacker running past the hijacked train with a South Moluccan flag | |

| Location | De Punt, Netherlands |

| Coordinates | 53°7′N 6°36′E / 53.117°N 6.600°E |

| Date | 23 May – 11 June 1977 (20 days) |

| Target | Train |

Attack type | Hostage-taking |

| Weapons | Guns, handguns |

| Deaths | 8 (including 6 perpetrators) |

| Injured | 6 |

| Perpetrators | Moluccan nationalists (9 perpetrators) |

| Motive | Establishment of the Republic of South Maluku |

On 23 May 1977, a train was hijacked near the village of De Punt, Netherlands. At around 9 am, nine armed Moluccan nationalists pulled the emergency brake and took over 50 people hostage. The hijacking lasted 20 days and ended with a raid by Dutch counter-terrorist special forces, during which two hostages and six hijackers were killed.

The same day as the train hijacking, four other Moluccans took over 100 hostages at a primary school in Bovensmilde, around 20 km (12 mi) away.

Background

Thousands of Moluccans fought in the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army after the Dutch government promised that they would eventually get their own independent state, the Republic of South Maluku.[1] However, following the Indonesian National Revolution, the unit was demobilized and Moluccan soldiers opted to settle in the Netherlands,[2] motivated by fears of reprisal attacks by Indonesians.[3] Many assumed that their stay would be temporary, and that with Dutch pressure, a Moluccan nation which they could return to would be established. However, by the 1970s, some had grown disillusioned, feeling that the Dutch government had reneged on its promises, leading to politically motivated violence.[4][5]

In 1975, ten Moluccans were arrested for conspiring to break into Soestdijk Palace and kidnap Queen Juliana. Later that year, 14 Moluccans simultaneously hijacked a train and held 41 people hostage at the Indonesian consulate at The Hague, leading to a 12-day hostage crisis which ended in three deaths.[6]

Planning

According to Willem S., the self-proclaimed leader of the hijacking, "I came up with the idea of taking action at the beginning of January this year... after Wijster and Amsterdam, the whole world had not understood what we South Moluccans want."[7] Initial targets included the town hall of Smilde and the headquarters of Nederlandse Omroep Stichting.[8]

Three hijackers cased the train route from Assen to Groningen and drew sketches of the train cars. According to one of the hijackers, "everything was arranged down to the smallest detail, including lists of items to take with you." They met up with the group responsible for the concurrent 1977 Dutch school hostage crisis on 21 May.[8]

Hijacking

At around 9 am on 23 May,[9] one of the hijackers (later identified as Matheus T.[8]) pulled the emergency brake, bringing the train to a stop near De Punt and allowing the others to board.[10] Around 40 people, including the crew, were allowed to leave.[11][12] The 54 passengers remaining on the train were forced to help cover all the windows with newspapers.[13] Warning shots were fired in order to frighten them into compliance.[8] At the same time, four Moluccans took six teachers and 105 students hostage at a nearby primary school.[11][12]

Members of the Bijzondere Bijstands Eenheid, Netherlands' special forces unit, quickly surrounded the train while a crisis team was set up in the Ministry of Justice headquarters.[10] In the initial confusion, Indonesian sailors waiting at Vlaardingen Oost metro station were mistakenly assumed to be part of the plot and detained.[14][15] Election campaigns for the soon-to-come 1977 Dutch general election were canceled by all major parties, so the Den Uyl cabinet could focus its attention on the incident.[10]

Contact between law enforcement and the hijackers was established on 24 May.[13] Among their demands was Dutch assistance in achieving Moluccan independence,[11] the release of 21 prisoners involved in previous attacks,[12] and a way to communicate with those at the school.[13] A deadline was set for 25 May at 2 pm, after which both groups threatened to set off explosives and kill all their hostages.[16] The Dutch government only fulfilled the third demand, providing them with a bugged phone line.[13]

The hijackers failed to carry out their threats once the deadline had passed, instead announcing another demand: fueled aircraft at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport, with which they could fly to a country of their choice.[17][18] The next day, three blindfolded passengers were briefly brought out with nooses around their necks in what a spokesman described as "perhaps a demonstration of power".[19] Authorities, however, stood firm and decided to cut the line between the train and the school.[13]

Negotiations

On 31 May, the hijackers requested that negotiators with whom they could talk to face-to-face be sent to the train.[20] After much deliberation, the crisis team selected Hassan Tan and Josina Soumokil (widow of Moluccan guerrilla Chris Soumokil), both well-respected members of the Dutch Moluccan community, to meet them.[21][22] The following day, as a sign of good faith, two pregnant women were let go on 5 June,[23][24][25] including Annie Brouwer-Korf, the future mayor of Utrecht.[12] Another person was let go due to heart problems on 8 June.[26][27]

On 9 June, during a second meeting with the hijackers,[28][29] Soumokil is suspected to have, without the knowledge or permission of the authorities, notified them that the People's Republic of Benin was willing to receive them.[30][31] By 10 June, they had become stubborn, again threatening to kill all the hostages if their demands weren't met.[13]

Rescue

On 11 June 1977 at 4:54 am, special forces started firing upon the train, shooting approximately 15,000 bullets in all.[4] In order to confuse the hijackers and divert their attention, six Lockheed F-104G Starfighter jet fighter aircraft flew over the area at low altitude, while a team of demolition experts set off explosives.[11] The train was then stormed, and most hostages freed. Six of the nine train hijackers, as well as two hostages, were killed in the assault.[11][12][13]

Aftermath

Three hijackers survived and, alongside their collaborators at the school, were given six- to nine-year prison sentences.[32][33][34] An accomplice was given a one-year sentence.[35] Riots occurred two weeks before the announcement of the verdict, resulting in two schools and a Red Cross centre being set on fire.[36] In 2007, a memorial service was held for the killed hijackers, which around 600 people attended.[37]

According to official sources, six of the hijackers were killed by bullets shot at the train from a distance. On 1 June 2013, reports emerged that an investigation by journalist Jan Beckers and one of the former hijackers, Junus Ririmasse, had concluded that three, and possibly four, of the hijackers had still been alive when the train was stormed, and had been executed by marines.[38] In November 2014, media reported that Justice Minister van Agt allegedly ordered military commanders to leave no hijackers alive.[39] An in-depth investigation, published the same month, concluded that no executions had taken place, but that unarmed hijackers had been killed by Marines.[40] In 2018, a Dutch court ruled that the Dutch government did not have to pay compensation to relatives of two of the hijackers killed by Marines. The ruling was upheld on appeal on 1 June 2021.[41]

In popular culture

In 2009, De Punt (television film), a Dutch- and Ambonese Malay-language television film was made about this hostage crisis, directed by Hanro Smitsman.[citation needed]

See also

- 1975 Indonesian consulate hostage crisis

- 1978 Dutch province hall hostage crisis

- Attempt at kidnapping Juliana of the Netherlands

- List of hostage crises

- Terrorism in the European Union

References

- ^ Buitelaar, Marjo; Zock, Hetty, eds. (2013). Religious Voices in Self-Narratives: Making Sense of Life in Times of Transition. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 194. ISBN 978-16-145-1170-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kahin, George McTurnan (1952). Nationalism and Revolution in Indonesia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 452.

- ^ Verschuur, Paul (8 October 1989). "40 Years Later, Moluccans Await Repatriation". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 28 October 2023. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ a b Paardekooper, Maurice (28 June 2018). Treinkaping De Punt 1977 - 2017: 40 jaar Molukse onvrede over de beëindiging van de gijzeling bij De Punt (MA thesis) (in Dutch). Leiden University. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ Smeets, Henk; Steijlen, Fridus (2006). In Nederland gebleven: de geschiedenis van Molukkers 1951-2006 [Stayed in the Netherlands: the History of Moluccans 1951-2006] (in Dutch). Amsterdam: Bert Bakker. ISBN 978-9035130982.

- ^ Rule, Sheila (9 June 1989). "Vught Journal; Remember the Moluccans? Is This a Last Stand?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ "Zuidmolukker Willem S.: "Ik leidde de acties"" [South Moluccan Willem S.: "I led the actions"]. Limburgs Dagblad (in Dutch). 7 September 1977. p. 3. Retrieved 31 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ a b c d "In gemeentehuis Smilde of NOS-Studio; kapers waren eerst uit op andere acties" [In Smilde town hall or NOS Studio; hijackers were initially after other actions]. Leeuwarder Courant (in Dutch). 7 September 1977. p. 3. Retrieved 31 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "By Extremists in Netherlands; Train Hijacked, School Occupied". Nashua Telegraph. Associated Press. 23 May 1977. p. 40. Retrieved 31 July 2024 – via Google Newspapers.

- ^ a b c "Treinkaping" [Train Hijacking]. Nieuwe Winterswijksche Courant (in Dutch). 23 May 1977. p. 2. Retrieved 31 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ a b c d e van Lent, Niek (29 November 2017). "Wat gebeurde er tijdens de Molukse treinkaping bij De Punt?" [What happened during the Moluccan train hijacking at De Punt?]. NPO Kennis (in Dutch). Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Hoe Nederland wekenlang zijn adem inhield bij treinkaping De Punt" [How the Netherlands held its breath for weeks at the De Punt train hijacking]. NOS (in Dutch). 29 May 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Royal Dutch Marines". Special Forces: Untold Stories. Season 1. Episode 2. 12 April 2002. TLC. Retrieved 31 July 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Indonesische zeelui zorgen in Vlaardingen voor paniek" [Indonesian sailors cause panic in Vlaardingen]. De Telegraaf (in Dutch). 24 May 1977. p. 1. Retrieved 31 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Kapings-syndroom" [Hijacking syndrome]. Amigoe (in Dutch). 24 May 1977. p. 1. Retrieved 31 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ ""Minister wilde Molukse treinkapers dood"" ["Minister wanted Moluccan train hijackers dead"]. De Morgen (in Dutch). 15 October 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ "Den Uyl wijst eisen kapers af; verwarring over bemiddelen" [Den Uyl rejects hijackers' demands; confusion about mediation]. De Volkskrant (in Dutch). 25 May 1977. p. 1. Retrieved 31 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Kapers, waarheen?" [Hijackers, where to?]. Algemeen Dagblad (in Dutch). 31 May 1977. p. 1. Retrieved 1 August 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Sfeer in Glimmen zeer gespannen tijdens 'demonstraties' kapers; mensen buiten trein" [Atmosphere in Glimmen very tense during 'demonstrations' of hijackers; people outside train]. Het Parool (in Dutch). 26 May 1977. p. 23. Retrieved 1 August 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Doorbraak in kaping; bemiddelen" [Breakthrough in hijacking; mediation]. Algemeen Dagblad (in Dutch). 1 June 1977. p. 1. Retrieved 1 August 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Bemiddelaars mevrouw Soumokil en dokter Tan gaan aan het werk; gesprek met kapers komt nu op gang" [Mediators Ms. Soumokil and Dr. Tan get to work; talks with hijackers now underway]. Leeuwarder Courant (in Dutch). 4 July 1977. p. 1. Retrieved 1 August 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Twee bemiddelaars; contact met kapers" [Two mediators; contact with hijackers]. Reformatorisch Dagblad (in Dutch). 4 July 1977. p. 1. Retrieved 1 August 2024 – via Digibron.

- ^ Hoffman, Paul (7 June 1977). "Dutch Seek to Improve Status of South Moluccans". The New York Times. p. 3. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ "Vrijgelaten vrouwen in voortreffelijke conditie; kans op zeer lange gijzeling" [Freed women in excellent condition; risk of very long hostage-taking]. Trouw (in Dutch). 6 June 1977. p. 1. Retrieved 2 August 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Kapers laten tweetal gaan zonder voorwaarden; vrijgelaten vrouwen allebei gezond" [Hijackers release pair without conditions; released women both healthy]. De Volkskrant (in Dutch). 6 July 1977. p. 1. Retrieved 1 August 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "After 17 Days on Train, Terrorists Free 3rd Hostage". The Victoria Advocate. Associated Press. 9 July 1977. p. 10A. Retrieved 2 August 2024 – via Google Newspapers.

- ^ "Man met hartklachten vanmorgen vrijgelaten; morgenmiddag tweede gesprek met treinkapers" [Man with heart problems released this morning; second interview with train hijackers tomorrow afternoon]. Leeuwarder Courant (in Dutch). 8 July 1977. p. 1. Retrieved 1 August 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Toch twee contactpersonen bij kapers in trein" [Still two contacts for hijackers on train]. NRC Handelsblad (in Dutch). 9 July 1977. p. 1. Retrieved 2 August 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Twee Zuidmolukkers bemiddelaars vanmiddag weer naar de trein" [Two South Moluccan mediators back on the train today]. Nederlands Dagblad (in Dutch). 9 July 1977. p. 1. Retrieved 2 August 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Zuidmoluske vrouw weigert verhoor; gevonden brief in kaaptrein leidt tot actie" [South Moluccan woman refuses interrogation; letter found on hijacked train leads to action]. De Volkskrant (in Dutch). 24 December 1977. p. 7. Retrieved 2 August 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Zuidmoluske: geen verhoor rechercheurs" [South Moluccan: no interrogation by detectives]. Trouw (in Dutch). 24 December 1977. p. 3. Retrieved 2 August 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Molukse kapers: 6 tot 9 jaar" [Moluccan hijackers: 6 to 9 years]. Het Vrije Volk (in Dutch). 22 September 1977. p. 1. Retrieved 31 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Zes tot negen jaar voor treinkapers en schoolbezetters; straf milder dan eis" [Six to nine years for train hijackers and school occupiers; punishment milder than demand]. Algemeen Dagblad (in Dutch). 23 September 1977. p. 6. Retrieved 31 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ Sloothaak, Jan (23 September 1977). "Zes tot negen jaar voor treinkaping; rechtbank weigert collectieve straf" [Six to nine years for train hijacking; court rejects collective punishment]. Trouw (in Dutch). p. 3. Retrieved 31 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ ""Gijzeling onaanvaardbaar middel": kapers en bezetters krijgen 6 tot 9 jaar" ["Unacceptable means of hostage-taking": hijackers and occupiers get 6 to 9 years]. De Volkskrant (in Dutch). 23 September 1977. p. 9. Retrieved 31 July 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Hostage Drama Sentences Set". Spokane Daily Chronicle. United Press International. 22 September 1977. Retrieved 31 July 2024 – via Google Newspapers.

- ^ "Herdenking voor kapers van trein bij De Punt (1977)" [Commemoration for train hijackers at De Punt (1977)]. NRC Handelsblad (in Dutch). 12 June 2007. Archived from the original on 16 July 2007. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ "'Treinkapers De Punt geliquideerd'" ['De Punt train hijackers liquidated']. Dagblad van het Noorden (in Dutch). 1 June 2013. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ "Train hijackers ordered executed by Justice minister". NL Times. 16 October 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ "Unarmed hijackers killed in train hijacking". NL Times. 20 November 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ "Dutch state does not have to pay damages for shooting Moluccan train hostage takers". Dutch News. June 2021. Archived from the original on 2 August 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

External links

![]() Media related to Dutch train hostage crisis 1977 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dutch train hostage crisis 1977 at Wikimedia Commons

- Article from 1977 in Time magazine

- Article in BBC "on this day"

- (in Dutch) Dutch Polygoon newsreel images from 1977

- (in Dutch) Dutch Polygoon newsreel images of the military action from 1977

- (in Dutch) Images from the armoured car unit involved in the action

- (in Dutch) Images in the Dutch National Archive

- South Moluccan Suicide Commando in MIPT Terrorism Knowledge Base