Antimony telluride

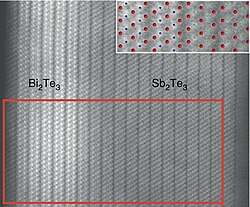

Electron micrograph of a seamless Bi2Te3/Sb2Te3 heterojunction and its atomic model (blue: Bi, green: Sb, red: Te)[1]

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

antimony telluride, antimony(III) telluride, antimony telluride, diantimony tritelluride

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.014.074 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Sb2Te3 | |

| Molar mass | 626.32 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | grey solid |

| Density | 6.50 g cm−3[2][3] |

| Melting point | 620 °C (1,148 °F; 893 K)[2] |

| Band gap | 0.21 eV[4] |

| Thermal conductivity | 1.65 W/(m·K) (308 K)[5] |

| Structure | |

| Rhombohedral, hR15 | |

| R3m, No. 166[6] | |

a = 0.4262 nm, c = 3.0435 nm

| |

Formula units (Z)

|

3 |

| Hazards | |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 0.5 mg/m3 (as Sb)[7] |

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 0.5 mg/m3 (as Sb)[7] |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Sb2O3 Sb2S3 Sb2Se3 |

Other cations

|

As2Te3 Bi2Te3 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Antimony telluride is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula Sb2Te3. As is true of other pnictogen chalcogenide layered materials, it is a grey crystalline solid with layered structure. Layers consist of two atomic sheets of antimony and three atomic sheets of tellurium and are held together by weak van der Waals forces. Sb2Te3 is a narrow-gap semiconductor with a band gap 0.21 eV; it is also a topological insulator, and thus exhibits thickness-dependent physical properties.[1]

Crystalline structure

Sb2Te3 has a rhombohedral crystalline structure.[8] The crystalline material comprises atoms covalently bonded to form 5 atom thick sheets (in order: Te-Sb-Te-Sb-Te), with sheets held together by van der Waals attraction. Due to its layered structure and weak inter-layer forces, bulk antimony telluride may be mechanically exfoliated to isolate single sheets.

Synthesis

Although antimony telluride is a naturally occurring compound, select stoichiometric compounds may be formed by the reaction of antimony with tellurium at 500–900 °C.[3]

- 2 Sb(l) + 3 Te(l) → Sb2Te3(l)

Applications

Like other binary chalcogenides of antimony and bismuth, Sb2Te3 has been investigated for its semiconductor properties. It can be transformed into both n-type and p-type semiconductors by doping with an appropriate dopant.[3]

Doping Sb2Te3 with iron introduces multiple Fermi pockets, in contrast to the single frequency detected for pure Sb2Te3, and results in reduced carrier density and mobility.[9]

Sb2Te3 forms the pseudobinary intermetallic system germanium-antimony-tellurium with germanium telluride, GeTe.[10]

Like bismuth telluride, Bi2Te3, antimony telluride has a large thermoelectric effect and is therefore used in solid state refrigerators.[3]

References

- ^ a b Eschbach, Markus; Młyńczak, Ewa; Kellner, Jens; Kampmeier, Jörn; Lanius, Martin; Neumann, Elmar; Weyrich, Christian; Gehlmann, Mathias; Gospodarič, Pika; Döring, Sven; Mussler, Gregor; Demarina, Nataliya; Luysberg, Martina; Bihlmayer, Gustav; Schäpers, Thomas; Plucinski, Lukasz; Blügel, Stefan; Morgenstern, Markus; Schneider, Claus M.; Grützmacher, Detlev (2015). "Realization of a vertical topological p–n junction in epitaxial Sb2Te3/Bi2Te3 heterostructures". Nature Communications. 6: 8816. arXiv:1510.02713. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.8816E. doi:10.1038/ncomms9816. PMC 4660041. PMID 26572278.

- ^ a b Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 4.48. ISBN 1-4398-5511-0.

- ^ a b c d Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 581–582. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Lefebvre, I.; Lannoo, M.; Allan, G.; Ibanez, A.; Fourcade, J.; Jumas, J. C.; Beaurepaire, E. (1987). "Electronic Properties of Antimony Chalcogenides". Physical Review Letters. 59 (21): 2471–2474. Bibcode:1987PhRvL..59.2471L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.2471. PMID 10035559.

- ^ Yáñez-Limón, J. M.; González-Hernández, J.; Alvarado-Gil, J. J.; Delgadillo, I.; Vargas, H. (1995). "Thermal and electrical properties of the Ge:Sb:Te system by photoacoustic and Hall measurements". Physical Review B. 52 (23): 16321–16324. Bibcode:1995PhRvB..5216321Y. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.52.16321. PMID 9981020.

- ^ Kim, Won-Sa (1997). "Solid state phase equilibria in the Pt–Sb–Te system". Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 252 (1–2): 166–171. doi:10.1016/S0925-8388(96)02709-0.

- ^ a b NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0036". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Anderson, T. L.; Krause, H. B. (1974). "Refinement of the Sb2Te3 and Sb2Te2se structures and their relationship to nonstoichiometric Sb2Te3–ySey compounds". Acta Crystallographica Section B. 30: 1307–1310. doi:10.1107/S0567740874004729.

- ^ Zhao, Weiyao; Cortie, David; Chen, Lei; Li, Zhi; Yue, Zengji; Wang, Xiaolin (2019). "Quantum oscillations in iron-doped single crystals of the topological insulator Sb2Te3". Physical Review B. 99 (16): 165133. arXiv:1811.09445. Bibcode:2019PhRvB..99p5133Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.99.165133. S2CID 119401198.

- ^ Wełnic, Wojciech; Wuttig, Matthias (2008). "Reversible switching in phase-change materials". Materials Today. 11 (6): 20–27. doi:10.1016/S1369-7021(08)70118-4.