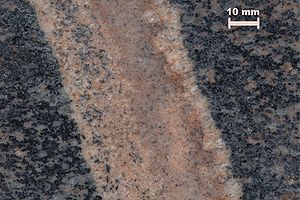

Aplite

Aplite (fine-grained center) | |

| Composition | |

|---|---|

| Quartz, feldspar |

Aplite (/ˈæplaɪt/) is an intrusive igneous rock that has a granitic composition. Aplites are fine-grained to aphanitic (without grains visible to the naked eye) and may consist of only quartz and feldspar or the term may refer to any leucocratic (pale-coloured) minor intrusion of that grain size.[1] They are associated with the later stages of many larger intermediate to felsic intrusions.

Occurrence

Aplites have a global distribution and have been described from most areas where there are significant granitic intrusions. They occur in the form of intrusive sheets, both within the associated granitic bodies and in the surrounding country rock.[2] Trace element analysis shows that there are no volcanic equivalents to aplites.[3]

Some aplites form in close association with pegmatites, which are otherwise uncommon in granites.[2] These aplite-pegmatite sheet complexes may show fine-scale banding with alternations of aplite and pegmatite.[4]

Syenite-aplites consist mainly of alkali feldspar; the diorite-aplites of plagioclase; there are nepheline-bearing aplites, including those containing the elaeolite variety of nepheline. In all cases, they bear the same relation to the parent masses.[5]

Formation

Aplites are intruded at a late stage in the history of the associated intrusion when crystallisation is at an advanced stage. In this state, the parent intrusion is mechanically coherent enough to support tensile stresses, leading to fractures. These fractures may then be filled by the remaining uncrystallised parts of the original magma (the residual fluids) to form the aplites.[2] There may be repeated phases of intrusion, solidification, fracturing and aplite dyke intrusion. This has been observed in the Half Dome granodiorite in Yosemite National Park, California, with multiple stages of aplite intrusion recognised, with the earlier aplite sheets becoming deformed by later intrusions into the main granodiorite body, but recognisable from their consistent chemistry.[3]

References

- ^ Le Maitre R.W.; Streckeisen A.; Zanettin B.; Le Bas M.J.; Bonin B.; Bateman P. (2005). Igneous Rocks: A Classification and Glossary of Terms: Recommendations of the International Union of Geological Sciences Subcommission on the Systematics of Igneous Rocks (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 9781139439398.

- ^ a b c Cobbing, J. (2000). The Geology and Mapping of Granite Batholiths. Springer-Verlag. p. 33. ISBN 3-540-67684-8.

- ^ a b Glazner, A.F.; Bartley, J.M.; Coleman, D.S.; Lindgren, K. (2020). "Aplite diking and infiltration: a differentiation mechanism restricted to plutonic rocks". Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 175 (4): 37. Bibcode:2020CoMP..175...37G. doi:10.1007/s00410-020-01677-1.

- ^ Breiter, K.; Ďurišová, J.; Hrstka, T.; Korbelová, Z.; Vašinová Galiová, M.; Müller, A.; Simons, B.; Shail, R.K.; Williamson, B.J.; Davies, J.A. (2018). "The transition from granite to banded aplite-pegmatite sheet complexes: An example from Megiliggar Rocks, Tregonning topaz granite, Cornwall". Lithos. 302–303: 370–388. Bibcode:2018Litho.302..370B. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2018.01.010. hdl:10871/31263.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Flett, John Smith (1911). "Aplite". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 168.