Ballet Russe de Monte-Carlo

| Ballet Russe de Monte-Carlo | |

|---|---|

| General information | |

| Name | Ballet Russe de Monte-Carlo |

| Year founded | 1937 |

| Closed | 1968 |

| Founders | Léonide Massine and René Blum |

| Principal venue | various |

| Senior staff | |

| Company manager | Sol Hurok |

| Artistic staff | |

| Artistic Director | Serge Denham (c. 1943–1968) |

| Ballet Master | Frederic Franklin (1944–1952) |

| Resident Choreographers | Léonide Massine (1937–1943) |

| Other | |

| Associated schools | School of American Ballet |

| Formation |

|

The company Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo (with a plural name) was formed in 1932 after the death of Sergei Diaghilev and the demise of Ballets Russes. Its director was Wassily de Basil (usually referred to as Colonel W. de Basil), and its artistic director was René Blum. They fell out in 1936 and the company split. The part which de Basil retained went through two name changes before becoming the Original Ballet Russe. Blum founded Les Ballets de Monte Carlo, which changed its name to Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo (note the singular) when Léonide Massine became artistic director in 1938. It operated under this name until it disbanded some 20 years later.[1]

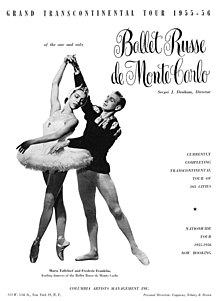

The Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo featured such dancers as Ruthanna Boris, Frederic Franklin, Alexandra Danilova, Maria Tallchief, Nicholas Magallanes,[2] Lois Bewley,[3] Tamara Toumanova, George Zoritch, Alicia Alonso, Elissa Minet, Yvonne Joyce Craig, Nina Novak, Raven Wilkinson, Meredith Baylis, Cyd Charisse, Marc Platt, Nathalie Krassovska, Irina Baronova, Leon Danielian, and Anna Adrianova. The company's resident choreographer was Massine; it also featured the choreography of Michel Fokine, Bronislava Nijinska, Frederick Ashton, George Balanchine, Agnes de Mille, Ruth Page and Valerie Bettis. Their costumes in the first season were made by Karinska,[4] and were designed by Christian Bérard, André Derain, and Joan Miró.[4]

The Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo toured chiefly in the United States and Canada after World War II began. The company introduced audiences to ballet in cities and towns across the country, in many places where people had never seen classical dance. The company's principal dancers performed with other companies, and founded dance schools and companies of their own across the United States and Europe. They taught the Russian ballet traditions to generations of Americans and Europeans.

History

Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo initially began because Léonide Massine, the choreographer of Colonel Wassily de Basil's Ballets Russes, desired to be more than just Colonel Wassily de Basil's right-hand man. De Basil was the artistic director of his Ballet Russes, and Massine desired that position, so he broke off to start his own company.[5]

Blum and de Basil fell out in 1934, and their Ballets Russes partnership dissolved.[6] After working desperately to keep ballet alive in Monte Carlo, in 1937 Blum and former Ballets Russes choreographer Léonide Massine acquired financing from Julius Fleischmann Jr.'s World Art, Inc. to create a new ballet company.[7]

At the start of Blum and Massine's company, Massine ran into trouble with Col. de Basil: the ballets which Massine choreographed while under contract with Col. de Basil were owned by his company. Massine sued Col. de Basil in London to regain the intellectual property rights to his own works. He also sued to claim the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo name.[8] The jury decided that Col. de Basil owned Massine's ballets created between 1932 and 1937, but not those created before 1932.[9] It also ruled that both successor companies could use the name Ballet Russe — but only Massine & Blum's company could be called Ballet Russe de Monte-Carlo. Col. de Basil finally settled on the Original Ballet Russe.[8]

The new Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo gave its first performance in 1938. Costumes were designed by British dancers Frederic Franklin and Jo Savino were also among those who joined the new company. Franklin danced with the company from 1938 to 1952, assuming the role of ballet master in 1944. With the company, Franklin and Alexandra Danilova created one of the legendary ballet partnerships of the twentieth century.

Sol Hurok, manager of de Basil's company since 1934, ended up managing Blum's company as well. He hoped to reunite the two ballet companies, but he was unsuccessful.

The Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and the Original Ballet Russe often performed near each other. In 1938, both the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and the Original Ballet Russe performed in London within blocks of each other.[8] Hurok continued to have the companies perform near each other. After London, Hurok booked both of the companies to perform seasons in New York, for a total of fifteen weeks, making it the longest ballet season of New York. Along with management, the two companies also shared dancers.

Co-founder René Blum was arrested on December 12, 1941, in his Paris home, among the first Jews to be arrested in Paris by the French police after France was defeated and occupied by the German Nazis during World War II. He was held in the Beaune-la-Rolande camp, then in the Drancy deportation camp. On September 23, 1942, he was shipped to the Auschwitz concentration camp,[10][11] where he was later killed by the Nazis.[6]

With Blum gone, Serge Denham, one of the co-founders of World Art, took over as company director.[12]

Massine left the company in 1943.

Based in New York from 1944 to 1948, the company's regular home was New York City Center.

In 1968, the company went bankrupt. Before then, many of its dancers had moved on to other careers; a number started their own studios and many taught ballet in larger studios, especially in New York and other major cities.

Works

- 1938

- Serge Lifar's Giselle (after Petipa, Coralli, Perrot), London

- 5 April premiere — Léonide Massine's Gaîté Parisienne, set to music by Jacques Offenbach, Théâtre de Monte-Carlo, Monte-Carlo, Monaco[13][14]

- 12 October premiere — Léonide Massine's Gaîté Parisienne, set to music by Jacques Offenbach, Metropolitan Opera House, New York[15]

- 1939

- Frederick Ashton's Devil's Holiday (Le Diable s'amuse)[16]

- Léonide Massine's La Boutique fantasque, set to the music of Ottorino Respighi

- Léonide Massine's Le Beau Danube

- 17 November premiere — Serge Lifar's Giselle (after Petipa, Coralli, Perrot), Metropolitan Opera House, New York City[17]

- 17 November — Léonide Massine's Gaîté Parisienne, Metropolitan Opera House, New York[17]

- 17 November — Michel Fokine's Scheherazade, Metropolitan Opera House, New York[17]

- 18 November premiere — Blue Bird, Metropolitan Opera House, New York[17]

- 18 November premiere — Marc Platoff's Ghost Town, set to music by Richard Rodgers,[18] Metropolitan Opera House, New York[17]

- 18 November — Michel Fokine's Les Sylphides and Petrushka, Metropolitan Opera House, New York[17]

- 18 November — Vaslav Nijinsky's Les Aprés-midi d'un Faune, Metropolitan Opera House, New York[17]

- 1940

- Alexandra Fedorova's (after Petipa)[19] The Nutcracker [abridged], set to music by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, New York City[20]

- 1941

- Léonide Massine's Labyrinth, New York

- Léonide Massine's Saratoga, New York

- Alexandra Fedorova's The Magic Swan (after Petipa), Metropolitan Opera House, New York

- 1942

- Alexandra Balachova's La Fille mal gardée

- 16 October premiere — Agnes de Mille's Rodeo, set to music by Aaron Copland, Metropolitan Opera House, New York

- 1943

- 9 October — Igor Schwezoff's The Red Poppy, Public Music Hall, Cleveland, Ohio[21]

- 1944

- George Balanchine's Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, set to the music of Jean-Baptiste Lully, New York City Center

- George Balanchine's Danses concertantes

- George Balanchine's Song of Norway, set to the music of Edvard Grieg, New York City

- 1945

- George Balanchine's Pas de Deux (Grand Adagio)

- Coppélia, set to the music of Léo Delibes

- 9 September — George Balanchine's Concerto Barocco, set to Johann Sebastian Bach's Concerto in D minor for Two Violins, New York City Center[22]

- 9 September — Vaslav Nijinsky's L'Après-midi d'un faune, New York City Center[22]

- 17 September premiere — Tod Bolender's Comedia Balletica, set to Igor Stravinsky's Pulcinella, New York City Center[22]

- 1946

- George Balanchine's La Sonnambula and The Night Shadow

- Balanchine and Alexandra Danilova's Raymonda, set to the music of Alexander Glazunov

- 1947

- Valerie Bettis' Virginia Sampler[23]

Legacy

Many of the company's principal dancers and corps de ballet founded dance schools and companies of their own across the United States and Europe, teaching the Russian ballet traditions to generations of Americans and Europeans.

Choreographers and principal dancers

- George Balanchine — founded the School of American Ballet (SAB) and New York City Ballet, for which he created works for 40 years.

- Alexandra Danilova — taught for 30 years at SAB.

- Leon Danielian — served as the director of SAB from 1967 to 1980.[24]

- Nicholas Magallanes – charter member of the New York City Ballet who performed roles created for him by Balanchine with the troupe from 1946 to 1976.[25]

- Maria Tallchief — danced with the New York City Ballet for years and was featured in choreography Balanchine created for her.

- Roya Curie — protégé of David Lichine and premier dancer with the Ballet Russe de Monte-Carlo International, she established a school in upstate New York in 1950.

- Frederic Franklin —became director of the National Ballet of Washington, D.C. Advised Dance Theatre of Harlem, as well as performing into his nineties.

- Jo Savino — formed the St. Paul Ballet in Minnesota.

- Robert Lindgren and Sonja Tyven (who danced in the Ballet Russe under the name Sonja Taanila) — opened the Lindgren-Tyven School of Ballet in Phoenix, Arizona (1959–1965). Lindgren also served as the founding dean of the influential dance school at the North Carolina School of the Arts, where Tyven taught ballet (1965–1987). Lindgren left NCSA when Lincoln Kirstein invited him to be his successor as director and president of the School of American Ballet, City Ballet’s affiliate school in New York (1987–1991).[26][27]

- George Verdak — taught for 25 years at Butler University and founded the Indianapolis Ballet Theatre.

Corps de ballet

- Marian and Illaria Ladre — in the late 1940s, they set up the Ballet Academy in Seattle, where they taught students who went on to dance and teach in their turn. Students of theirs who had professional dance careers included James De Bolt of the Joffrey Ballet, Cyd Charisse, Marc Platt, Harold Lang, and Ann Reinking. In 1994 Illaria Ladre was among the first American dancers, choreographers and writers honored by receiving the newly established Vaslav Nijinsky Medal, sponsored by the Polish Artists Agency in Warsaw, for work carrying on the tradition of Nijinsky.[28]

- Lubov Roudenko — Former soloist for the Ballets Russes in the 1930s, she left in the 1940s and, as Luba Marks, became a successful Coty Award winning fashion designer.[29]

- Elissa Minet — danced for one season with the Ballets Russes in 1937 before joining the ballet company at the Metropolitan Opera.[30]

In popular culture

A feature documentary about the company, featuring interviews with many of the dancers, was released in 2005, with the title Ballets Russes.

References

Notes

- ^ Koegler, Horst, Concise Oxford Dictionary of Ballet (1st English edition, 1977).

- ^ [1] Nicholas Magallanes Obituary – performed with Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo (1943–1946) on NYTimes.com

- ^ Weber, Bruce (November 29, 2012). "Lois Bewley, Multifaceted Ballerina, Dies at 78". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Barbara Karinska: Costume Couturier". Dance Teacher. November 9, 2008. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ Cohen, Selma Jeanne (2005). "Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo". The international Encyclopedia of Dance. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517369-7.

- ^ a b Homans, Jennifer. "René Blum: Life of a Dance Master," New York Times (July 8, 2011).

- ^ "Blum Ballet Sold to Company Here," New York Times (Nov. 20, 1937).

- ^ a b c Andros, Gus Dick (February 1997). "Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo". Andros on Ballet. Michael Minn. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ^ australiadancing[usurped] through the Internet Archive

- ^ Gilbert, Martin (2002). The Routledge Atlas of the Holocaust. Psychology Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-415-28145-4.

- ^ The Trial of Adolf Eichmann, Session 32 (Part 5 of 5) Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Georges Wellers testimony at the trial of Eichmann.

- ^ "The Company’s Metamorphosis," Russian Ballet History: Diaghilev's Ballet Russes, 1909–1929. Accessed March 25, 2015.

- ^ Jack Anderson, The One and Only: The Ballet Russe de Monte-Carlo (New York: Dance Horizons, 1981), p. 281.

- ^ Frederic Franklin, interviewed by John Mueller, Cincinnati, Ohio, October 2004; bonus material on Gaîté Parisienne, a film (1954) by Victor Jessen on DVD (Pleasantville, N.Y.: Video Artists International, 2006).

- ^ Balanchine and Mason, 101 Stories of the Great Ballets (1989), p. 183.

- ^ "Sir Frederick Ashton – Great Choreographer and founder-figure of British ballet" TheTimes 20 August 1988

- ^ a b c d e f g J. M. "'GISELLE' PERFORMED BY THE BALLET RUSSE: Mia Slavenska Dances Title Role at the Metropolitan," New York Times (Nov. 18, 1939).

- ^ Kisselgoff, Anna. "DANCE REVIEW; Rodgers As Ideal Dance Partner," New York Times (Oct. 23, 2002).

- ^ "Nutcracker History". Balletmet.org. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- ^ "Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo records, 1935–1968 (MS Thr 463) Harvard University library". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ "The Red Poppy: The Ballet Russe Collection," Archived March 3, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Butler University Department of Dance. Accessed Feb. 14. 2015.

- ^ a b c Martin, John. "THE DANCE: BALLET RUSSE: Monte Carlo Company to Present New Works in City Center Season," New York Times (August 26, 1945).

- ^ Amberg, George (2007). Ballet in America – The Emergence of an American Art. Read Books. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-4067-5380-6.

- ^ Anderson, Jack (March 12, 1997). "Leon Danielian, 75, Ballet Star Known for His Wide Repertory". The New York Times. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ The New York Times – Nicholas Magallanes Obituary on nytimes.com

- ^ KISSELGOFF, ANNA (May 15, 2013). "Robert Lindgren, 89, Ballet Dancer and College Dean, Is Dead". The New York Times. Retrieved May 17, 2013.

- ^ Whitaker, Lauren. "ROBERT LINDGREN, FOUNDING DEAN OF UNCSA SCHOOL OF DANCE, HAS DIED Winston-Salem resident was known throughout the world of dance". UNCSA. Retrieved May 17, 2013.

- ^ Awards to Americans in Honor of Nijinsky, New York Times, 26 November 1994, Accessed 15 November 2007

- ^ Sheppard, Eugenia (September 12, 1966). "Ballerina is Heroine of Medium Price Coat". The Daily Times-News, Burlington. Retrieved March 20, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "December 2011/January 2012 O.Henry Magazine by O.Henry magazine - Issuu".

Sources

- "Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo". Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1994–2010. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- "Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo". The Oxford Dictionary of Dance. Oxford University Press. 2004 [2000]. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- Ballets Russes, 2005 documentary

Further reading

- Garcia-Marquez, Vicente (1990). The Ballets Russes: Colonel de Basil's Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo 1932-152. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-52875-1.

- Sorley Walker, Kathrine (1982). De Basil's Ballets Russes. New York: Atheneum. ISBN 0-689-11365-X.

- Anderson, Jack (1981). The One and Only: The Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Dance Horizons. ISBN 0-87127-127-3.

External links

- Guide to the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo Press Clipping Scrapbooks. Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California.

- Guide to Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo records at Houghton Library, Harvard University

- Ballet Foundation collection of Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and Ballet Theatre photographs, 1920s-1980s, held by the Dance Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

| Archives at | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| How to use archival material |