Baroque garden

The Baroque garden was a style of garden based upon symmetry and the principle of imposing order on nature. The style originated in the late-16th century in Italy, in the gardens of the Vatican and the Villa Borghese gardens in Rome and in the gardens of the Villa d'Este in Tivoli, and then spread to France, where it became known as the jardin à la française or French formal garden. The grandest example is found in the Gardens of Versailles designed during the 17th century by the landscape architect André Le Nôtre for Louis XIV. In the 18th century, in imitation of Versailles, very ornate Baroque gardens were built in other parts of Europe, including Germany, Austria, Spain, and in Saint Petersburg, Russia. In the mid-18th century the style was replaced by the less geometric and more natural English landscape garden.

Characteristics

Baroque gardens were intended to illustrate the mastery of man over nature. They were often designed to be seen from above and from a little distance, usually from the salons or terraces of a château. They were laid out like rooms in a house, in geometric patterns, divided by gravel alleys or lanes, with the meeting points of the lanes often marked by fountains or statues. Flower beds were designed like tapestries, with bands of shrubbery and flowers forming the designs. Larger bushes and trees were sculpted into conical or dome-like shapes, and trees were grouped in bosquets, or orderly clusters. Water was usually present in the form of long rectangular ponds, aligned with the terraces of the house, or circular ponds with fountains. The gardens usually included one more small pavilion, where visitors could take shelter from the sun or rain.

Over time, the style evolved, and became more natural. Grottoes and "secret gardens" enclosed by trees appeared, to illustrate the literary ideals of Arcadia and other popular stories of the time; these were usually placed in the outer corners of the garden, to give suitable places for quiet reading or conversation.[1]

Origins in Italy

The ideas that inspired the Baroque garden, like those of Baroque architecture, first appeared in Italy in the late Renaissance. In the late 15th century, the architect, artist and writer Leon Battista Alberti proposed that the house and garden were both sanctuaries from the confusion of the outside world and that they both should be designed with architectural forms, geometric rooms, and corridors. In a very popular allegorical story, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (The Song of Poliphile) (1499), one of the first printed novels, the Dominican priest and author Francesco Colonna described a garden composed of carefully designed ornamental flowerbeds and rows of trees shaped in geometric forms.[2]

The Cortile del Belvedere or courtyard of the Belvedere at the Vatican in Rome was one of the first gardens in Europe which adopted these geometric principles, and was a model for many later Baroque gardens. It was begun in 1506, constructed for Pope Julius II, in connected his residence on a nearby hillside with the Vatican. The garden was three hundred meters long, filled with orderly flower beds and gardens geometrically divided by alleys and hedges, with fountains at the intersections of the paths. It was finished in 1565 by Pirro Ligorio. The original garden was drastically modified by the later addition of the Vatican Library.

The same architect who completed the Cortile del Belvedere, Pirro Ligorio, was commissioned in the same year to design an even more ambitious garden, Villa d'Este, for Cardinal Ippolito II d'Este (1509–1572). This garden was designed on a steep hillside, which could be viewed from the Villa above. The garden was composed of five terraces, elaborately planted in geometric forms and connected with ramps and stairways. Like many Baroque gardens, it was best viewed from above and from a distance, to get the full effect.[3]

This architectural form for gardens continued to dominate in Italy until the construction of Villa Borghese gardens in Rome by Cardinal Scipione Borghese in 1605. In this very large garden, the regular and geometric alleys, flowerbeds and groves of aligned trees were joined by other parts of the garden in asymmetrical forms, and by a number of "secret gardens", small sanctuaries of trees and flowers planted with flowers and fruit trees, and surrounded by rows of oak trees, laurel and cypress trees, and populated with birds and animals. This garden marked the beginning of the transition to the more natural landscape garden, based on the romantic vision of an imaginary Arcadia.[4]

All of these gardens underwent extensive redesign in the 18th century, turning them into more natural-looking landscape gardens. Except in a few preserved paths and flower beds, it is difficult now to imagine them in their original state.

-

The gardens of the Cortile del Belvedere are visible to the left of this 1652 engraving of the Vatican

-

Gardens of the Villa d'Este, engraving by Etienne Duparac (1573)

-

A vestige of the original Baroque garden at the Villa Borghese

The Jardin à la française

At the end of the 15th century, Charles VIII of France invited Italian architects and garden designers to France to create an Italian garden for his Château d'Amboise. In the 16th century, the development of the Baroque garden in France was accelerated by Henry IV of France and his Florentine wife, Marie de' Medici. Their first major project in the style was the garden of the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, near Paris. The new garden, on the bluff above the Seine, featured an extensive belvedere with ramps and stairways, scattered with an assortment of pavilions, grottoes, and theatres. Following the assassination of the King, his widow built a palace and a garden of her own, now called the Jardin du Luxembourg. She planted groves of full-grown trees and laid out parterres, alleys and fountains on the model of the gardens of her native Florence.[5]

The French Baroque garden reached its summit under Louis XIV, due to his garden designer, André Le Nôtre. Le Nôtre's first large-scale project was for Vaux-le-Vicomte, the château of the King's Superintendent of Finances, Nicolas Fouquet, built between 1656 and 1661. The central feature of this garden was a main axis descending from the château, composed of a series of terraces decorated with parterres of low hedges in ornamental designs. Large basins with jeux d'eau were placed along the central axis, and the garden was set between rows of trimmed trees on the left and right, to lead the eye on the long perspective to the last fountain and grotto below. The garden was meant to be seen from the château, which overlooked it like the box of a theater.[6]

The young Louis XIV had Fouquet imprisoned for his extravagance, but greatly admired the garden he created. He commissioned Le Nôtre to design a similar, but vastly larger, garden, for his own projected Palace of Versailles.

The most famous Baroque gardens were the Gardens of Versailles created by Le Nôtre between 1662 and 1666. It was built around the original small square park of ninety-three hectares before the château started for Louis XIII by Jacques Boyceau in 1638. In 1662 following the model of Vaux-le-Vicomte, Le Nôtre made the park ten times larger, centered on a grand canal which reached to the horizon. The new park was divided into an elaborate grid of flowerbeds, paths, and alleys, decorated with fountains and sculptures. A third enlargement expanded the park by another six thousand five hundred hectares, including forests for hunting and several nearby villages, surrounded by a wall forty-three kilometres long with twenty-two gates.[7]

The centrepiece of the garden was the Fountain of Apollo, the symbol of Louis XIV, the sun king himself, surrounded by a network of paths, basins, colonnades, theaters, and monuments. The King himself designed the route that visitors should follow, with twenty-five different mythological scenes, stations, and panoramas. The garden became an outdoor theatre for pageants, promenades, theatre performances, and fireworks shows. Its greatest deficiency was insufficient water for all of the fountains; only a few fountains could work at the same time; they were turned on only when the King was approaching them.[8]

Between 1676 and 1686, Louis XIV built a smaller version of the Versailles gardens at the Château de Marly, located in a more tranquil valley, where he could escape from the crowds of Versailles. After his death in 1715, portions of the Gardens of Versailles were gradually modified to the new style of an English landscape garden, with trees untrimmed and planted in more natural groves, winding paths, and replicas of Greek temples and even a picturesque model village for the amusement of Marie Antoinette. The gardens of Versailles had many royal visitors, including Peter the Great of Russia, and many of its features were imitated in other European palace gardens.[9]

-

Garden of Vaux-le-Vicomte seen from the château (1656–1661)

-

View of the garden façade of Palace of Versailles in 1680s

-

Plan of the Tuileries Garden (about 1671)

-

Gardens of the Château de Marly (1724)

Germany

The Baroque garden style was first introduced to Germany in 1614 by Frederick V of the Palatinate, who imported a French landscape architect, Salomon de Caus, and began building a garden called the Hortus Palatinus at his castle in Heidelberg. The hilltop location, overlooking the Rhine, limited the size and presented difficult terrain, but de Caus succeeded in building a series of parterres with concentric circles of greenery, a circular fountain, and a bosquet of laurel trees, ingeniously linked by stairways and ramps.[10]

The style soon appeared in at the castles of other German princes, including Herrenhausen in Hanover, built at the end of the 17th century. Its designer, Martin Charbonnier, was French, and he included the classic Versailles elements, including a central axis aligned with the castle, a circular pond at the far end of the axis, bouquets of trees, and "secret gardens", small gardens enclosed by trees, places for reading or quiet conversation, at the edges of the garden. He also borrowed some features of Dutch gardens, which he had visited in his research, including a canal surrounding the garden and wedge-shaped parterres surrounded by low hedges.[11]

Another notable Baroque garden in Germany is the Schlosspark, Brühl (1728), designed by Dominic Girard, who was a pupil of Le Nôtre at Versailles. Like Versailles, it features a central axis flanked by ornamental parterres and circular basins with fountains, all flanked by alleys and geometrically trimmed rows of the trees.

Other notable Baroque gardens in Germany include the Großer Garten in Dresden, Bergpark Wilhelmshöhe near Kassel, the garden of Weikersheim Castle (1707–1725), and the gardens of Nymphenburg Palace (1715–1720), which rivaled the Gardens of Versailles in size. The Baroque age in German gardens came to an end with the construction of the garden of Schwetzingen Palace, made in 1753–58 for the Elector Palatine Charles Theodore, by architect Nicolas de Pigage and gardener Johann Ludwig Petri. This garden was filled with artificial Roman ruins, a Chinese bridge, a mosque and other picturesque landmarks; it marked the debut of the romantic English landscape garden in Germany.[12]

-

The Hortus Palatinus in Heidelberg, overlooking the River Neckar and the Rhine Valley (begun 1614)

-

Herrenhausen in Hannover (end of 17th century)

-

Parterres of Schlosspark, Brühl by Dominique Girard (1728)

Austria and the Netherlands

The pupils of Le Nôtre were in demand across Europe, recreating the canals and parterres of French gardens for other European monarchs. One of the most prolific and successful designers was Dominique Girard, who designed the elegant curling patterns of the parterres of the Belvedere Palace in Vienna for Prince Eugene of Savoy. This garden was largely influenced by Le Nôtre, but also by the more modern ideas of Antoine-Joseph Dezallier d'Argenvilles, whose book Treatise on the practice and theory of gardening (1709), became the most influential manual of landscape design in the early 18th century.[13]

Begun in 1717, the garden connected the two palaces of the Prince. The upper palace and garden was used for grand ceremonies, while the lower garden, by his residence, was arranged with groves of trees and crisscrossed by paths. A large water basin on the upper terrace was connected by stairs and cascades, filled with statues of nymphs and goddesses to the lower garden. The parterres were destroyed and replaced with grass in the eighteenth century, but have recently been restored to their original appearance.[14]

A portion of the Netherlands, the United Provinces, had won its independence from the Spanish Netherlands, and in 1684–86 its ruler William III, the future king of England, constructed the Het Loo Palace with a magnificent Baroque garden. The garden was designed by Claude Desgots, who was the nephew of Le Nôtre; he earlier had reworked the design of the Jardin du Luxembourg and designed the Tuileries Gardens in Paris. The upper garden of Het Loo was primarily inspired by Versailles, with paths radiating from a central alley, while the lower garden, in front of the palace, showed a Dutch influence, divided into independent sections, each different, and divided by alleys lined with the characteristic hedges and trees of the Dutch countryside.[15]

-

Baroque garden at Schloss Hof

-

Restored parterres of the Belvedere Palace today

-

Het Loo Palace in the Netherlands

-

Het Loo Palace in the Netherlands

Spain and Naples

Philip V of Spain, the grandson of Louis XIV, who had spent his childhood at Versailles, was responsible for introducing the Baroque garden to Spain. At the beginning of the 18th century, he created a garden modelled after Versailles at the Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso, not far from Segovia. The uneven landscape, a thousand meters in altitude, made it difficult to have extensive parterres, but it provided an abundance of water.[16] The garden designer was René Carlier, who had worked under Robert de Cotte, one of the leading French royal architects.[17] He used the natural slope of the site in the palace grounds design, for enhancing axial visual perspectives, and to provide sufficient head for water to shoot out/up from the twenty-six sculptural fountains in the formal gardens and the later landscape park.

Philip's successor, Charles III of Spain, also created a notable Baroque garden in the Kingdom of Naples, which he ruled. It was located at Caserta, not far from Naples. As at Granja, the garden was surrounded by hills, while the palace was surrounded by canals, fountains, and geometric parterres decorated with low hedges in Baroque designs.[18]

-

Cascade and alleys at the Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso

-

Fountain sculpture in the gardens of the Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso

-

Cascades in the royal park of the Palace of Caserta

Sweden

The French garden designer André Mollet came to Sweden in the late 1640s and his stay lasted five years, during which he introduced to Sweden the French parterres en broderie patterned like Baroque textiles. He modernized the existing gardens linked to the Stockholm Palace and laid out a new garden in the outskirts of Stockholm on the site of a former hop-garden, the Humlegården. The introduction of a Baroque garden style in Sweden dates to this decade, with the encouragement of progressive Francophile architects like Nicodemus Tessin the Elder and Jean de la Vallée, with whom Mollet had worked in Holland, together with the eager commissions from Swedish nobles that Mollet received. The results are documented in Erik Dahlbergh's topographical Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna. Though Mollet left Sweden in 1653, his son Jean Mollet remained in Sweden for the rest of his life, and Médard Gue, one of André Mollet's original French assistants, assumed an independent role in Swedish gardening. Nicodemus Tessin the Elder laid out the gardens at Ekolsund Castle in the new Baroque style in the 1660s, mainly based on the André Le Nôtre's work at Vaux le Vicomte.

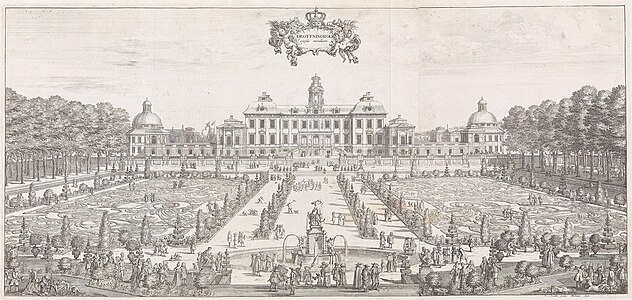

Nicodemus Tessin the Elder's son, Nicodemus Tessin the Younger, also became an architect and during the 1670s he spent time in Italy, France and England. During his visit to France in 1677–1678 he spent a great deal of time with Le Nôtre, who had a lasting influence of Tessin's garden designs. He again visited France in the 1680s. The gardens at Drottningholm Palace where laid out by him in the Baroque style.

-

Plan for the gardens at Ekolsund, by Tessin the Elder (1660s)

-

Gardens at Ekolsund in the 1690s

-

The gardens at Drottningholm Palace in 1692

-

The Baroque garden at Drottningholm Palace in 2011

-

The fountain of Hercules at Drottningholm Palace

Russia

Peter the Great visited the Palace of Versailles and the Palace of Fontainebleau in 1717 during his European tour, and upon his return to Russia began constructing a garden at the Peterhof Palace, begun in 1714, in the Versailles style. He brought the French architect Jean-Baptiste Alexandre Le Blond to St. Petersburg to design gardens for his new capital city and for his new palace. It was completed in 1728.[19]

Peterhof was located on the side of the steep slope overlooking the Gulf of Finland. The new plans called for a formal garden on the upper terrace, and for a grand cascade pouring down the hillside from the palace to a canal, with fountains, leading out to the Gulf. The grand cascade was modeled after that of the Château de Marly, the smaller palace and retreat of Louis XIV near Versailles. The Gardens were laid out in bosquets and alleys of trees in symmetrical patterns, similar to Versailles.

A less-known Baroque garden in St. Petersburg is the park of Oranienbaum (1710–27), that was given by Peter to one of his most prominent nobles, Alexander Danilovich Menshikov.

The Russian Baroque gardens were much modified in the later 18th century to the more natural English landscape garden style; the trees and flower beds were not trimmed, and more natural flowerbeds and winding paths replaced the original parterres. In recent years, some of the parterres have been restored to their original Baroque appearance.

-

The upper gardens and parterres of Peterhof, now grown up and more natural than their original Baroque appearance

-

Gardens of the Grand Menshikov Palace in Oranienbaum (1710–1727)

-

Grand Cascade and fountains of Peterhof Palace, facing the Gulf of Finland (1714–28)

Decline of the Baroque garden

Baroque gardens were extremely expensive to build and to maintain; they required large numbers of gardeners and continual trimming and upkeep, as well as intricate systems of irrigation to provide water. At times a large portion of the French army was devoted to digging channels and constructing systems to bring water to the gardens of Versailles.

Descriptions of English gardens were first brought to France by Jean-Bernard, abbé Le Blanc, who published accounts of his voyage in 1745 and 1751. A treatise on the English garden, Observations on Modern Gardening, written by Thomas Whately and published in London in 1770, was translated into French in 1771. After the end of the Seven Years' War in 1763, French noblemen were able to voyage to England and see the gardens for themselves, and the style began to be adapted in French gardens. The new style also had the advantage of requiring fewer gardeners, and was easier to maintain, than the French garden.[20]

One of the first English gardens on the continent was at Ermenonville, in France, built by marquis René Louis de Girardin from 1763 to 1776 and based on the ideals of Jean Jacques Rousseau, who was buried within the park. Rousseau and the garden's founder had visited Stowe a few years earlier. Other early examples were the Désert de Retz, Yvelines (1774–1782); the Gardens of the Château de Bagatelle, in the Bois de Boulogne, west of Paris (1777–1784); The Folie Saint James, in Neuilly-sur-Seine, (1777–1780); and the Château de Méréville, in the Essonne department, (1784–1786). Even at Versailles, the home of the most classical of all French gardens, a small English landscape park with a Roman temple was built by the Petit Trianon and a mock village, the Hameau de la Reine, Versailles (1783–1789), was created for Marie Antoinette.

The new style also spread to Germany. The central English Grounds of Wörlitz, in the Principality of Anhalt, was laid out between 1769 and 1773 by Leopold III, based on the models of Claremont, Stourhead, and Stowe landscape gardens. Another notable example was The Englischer Garten in Munich, Germany, created in 1789 by Sir Benjamin Thompson (1753–1814). These marked the transition and soon the end of the baroque garden in Europe.

Notes and citations

- ^ Kluckert, "Les Jardins Baroques", in L'Art Baroque – Architecture- Sculpture- Peinture (2015), p. 152

- ^ Kluckert, "Les Jardins Baroques", in L'Art Baroque – Architecture- Sculpture- Peinture (2015), p. 152

- ^ Kluckert (2015) p. 152

- ^ Kluckert (2015) p. 152

- ^ Kluckert, "Les Jardins Baroques", in L'Art Baroque – Architecture- Sculpture- Peinture (2015), p. 153

- ^ Kluckert, "Les Jardins Baroques", in L'Art Baroque – Architecture- Sculpture- Peinture (2015), p. 154–155

- ^ Kluckert (2015) p. 154

- ^ Kluckert (2015) pp. 154–155

- ^ Kluckert (2015) pp. 154–155

- ^ Kluckert (2015) pp. 158–159

- ^ Kluckert (2015) pp. 158–159

- ^ Ingrid Dennerlein: Die französische Gartenkunst des Régence und des Rokoko, Worms 198x In German

- ^ Kluckert (2015) p. 160

- ^ Kluckert (2015) p. 160

- ^ Kluckert (2015) p. 160

- ^ Patrimonio Nacional: Gardens of the Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso Archived 2016-01-27 at the Wayback Machine, "History" tab.

- ^ Carlier died in 1722, having laid out the main structural features, Esteban Boutelou continued in his place. Jeanne Digard, Les jardins de la Granja et la sculpture décorative (Paris) 1934.

- ^ Kluckert (2015) p. 161

- ^ "Second Northern War | Europe [1700–1721]". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- ^ Allain and Christiany, pp. 316–318.

Bibliography

- Allain, Yves-Marie and Christiany, Janine L'art des jardins en Europe, Citadelles and Mazenod, Paris, 2006

- Attlee, Helena. Italian Gardens – A Cultural History, Francis Lincoln Limited Publishers, 2006

- Lucia Impelluso, Jardins, potagers et labyrinthes, Hazan, Paris, 2007.

- Claude Wenzler, Architecture du jardin, Editions Ouest-France, 2003

- Kluckert, Ehrenfried, Section on Baroque Gardens in L'Art Baroque – Architecture – Sculpture – Peinture (French translation from German), H.F. Ulmann, Cologne, 2015. (ISBN 978-3-8480-0856-8)

- Philippe Prevot, Histoire des jardins, Editions Sud Ouest, 2006

- Impelluso,Lucia. Jardins, potagers et labyrinthes, Editions Hazan, Paris, 2007

- Medvedkova, Olga, Jean-Baptiste Alexandre Le Blond, architecte 1679–1719 – De Paris à Saint-Pétersbourg, Paris, Alain Baudry & Cie, 2007, ISBN 978-2-9528617-0-0