Big Horn Basin

The Bighorn Basin is a plateau region and intermontane basin, approximately 100 miles (160 km) wide, in north-central Wyoming in the United States. It is bounded by the Absaroka Range on the west, the Pryor Mountains on the north, the Bighorn Mountains on the east, and the Owl Creek Mountains and Bridger Mountains on the south. It is drained to the north by tributaries of the Bighorn River, which enters the basin from the south, through a gap between the Owl Creek and Bridger Mountains, as the Wind River, and becomes the Bighorn as it enters the basin. The region is semi-arid,[1] receiving only 6–10 in (15–25 cm) of rain annually.

The largest cities in the basin include the Wyoming towns of Cody, Thermopolis, Worland, and Powell. Sugar beets, pinto beans, sunflowers, barley, oats, corn and alfalfa hay are grown on irrigated farms in the region.

History

The basin was explored by John Colter in 1807. Just west of Cody, he discovered geothermal features that were later popularly called "Colter's Hell". The region was later transversed by the Bridger Trail, which was blazed in 1864 by Jim Bridger to connect the Oregon Trail to the south with Montana. The route was an important alternative to the Bozeman Trail, which had crossed the Powder River Country, but had been closed to white settlers following Red Cloud's War. Around the turn of the 20th century the Bighorn Basin was settled by ranchers such as William "Buffalo Bill" Cody who founded the town of Cody and owned a great deal of land surrounding the Shoshone River. The Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad extended a branch line to Cody in 1901 and ultimately built through the entire basin. In 1904, Cody helped to form the Shoshone project, the nation's first federal water development project to help irrigate the western portion of the basin. The project culminated in the construction of the Buffalo Bill Dam and reservoir. The wealth in the region also attracted outlaws. Butch Cassidy lived near Meeteetse for a while and was arrested at the insistence of local cattle baron Otto Franc and sent to the Wyoming State Penitentiary for horse theft. Following his release, he formed the Wild Bunch gang which operated from the Hole-in-the-Wall area southeast of the Bighorn Basin.

In 1942 one of the nation's ten Japanese American internment camps was located in Park County in the western part of the basin. The camp was named Heart Mountain Relocation Center, after nearby Heart Mountain. The camp operated until 1945, and at its peak detained over 10,000 internees.

Geology

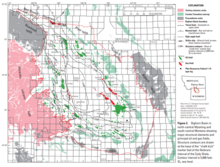

The Bighorn Basin forms a geologic structural basin filled with more than 20,000 feet (6,100 m) of sedimentary rocks from Cambrian to Miocene in age. Since the early 20th century the basin has been a significant source of petroleum, and has produced more than 1,400,000,000 barrels (220,000,000 m3) of oil. The principal reservoir of oil is the Pennsylvanian Tensleep Formation; Other important petroleum horizons are the Mississippian Madison Limestone, Permian Phosphoria Formation and the Cretaceous Frontier Sandstone.[2]

Some uranium has been mined in the northern part of the basin, along the Bighorn Mountains.

The eastern section of the basin is famously rich in fossils, with formations such as the Cretaceous period Cloverly Formation yielding numerous dinosaur fossils.

The alluvial strata of the Willwood and Fort Union Formations of the Bighorn Basin contain a well-documented record of the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM).[3] Analysis of paleosols here shows that the Bighorn Basin became more arid during the PETM, with wet/dry cycles superimposed over this general increase in aridity.[4] These changes in environment are coupled with changes in paleoecology.[5][6]

Communities

Notable Features

See also

- Uranium mining in Wyoming

- Wind River Basin

- Wyoming Basin shrub steppe

- Bighorn Basin Dinosaur Project

References

- ^ Gray S.T. (2004). "Tree-Ring-Based Reconstruction of Precipitation in the Bighorn Basin, Wyoming, since 1260 A.D." Journal of Climate. 17 (19): 3855–3865. Bibcode:2004JCli...17.3855G. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2004)017<3855:TROPIT>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ John P. Weldon (1972) The Big Horn Basin in Geologic Atlas of the Rocky Mountain Region, Denver: Rocky Mountain Association of Geologists, p.270-272.

- ^ Clyde, William C.; Hamzi, Walid; Finarelli, John A.; Wing, Scott L.; Schankler, David; Chew, Amy (2007). "Basin-wide magnetostratigraphic framework for the Bighorn Basin, Wyoming". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 119 (7–8): 848. Bibcode:2007GSAB..119..848C. doi:10.1130/B26104.1.

- ^ Kraus, Mary J.; Riggins, Susan (2007). "Transient drying during the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM): Analysis of paleosols in the bighorn basin, Wyoming". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 245 (3–4): 444. Bibcode:2007PPP...245..444K. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.09.011.

- ^ Gingerich, P.D. (2003). "Mammalian responses to climate change at the Paleocene-Eocene boundary: Polecat Bench record in the northern Bighorn Basin, Wyoming". In Wing, S.L.; Gingerich, P.D.; Schmitz, B.; Thomas, E. (eds.). Causes and consequences of globally warm climates in the early Paleogene. pp. 463–478. ISBN 978-0-8137-2369-3.

- ^ Currano, E. D.; Wilf, P.; Wing, S. L.; Labandeira, C. C.; Lovelock, E. C.; Royer, D. L. (2008). "Sharply increased insect herbivory during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (6): 1960–4. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.1960C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0708646105. hdl:10088/5942. PMC 2538865. PMID 18268338.