Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park

| Black Canyon of the Gunnison | |

|---|---|

Gunnison River at the base of Black Canyon of the Gunnison | |

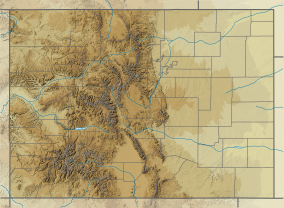

| Location | Montrose County, Colorado, United States |

| Nearest city | Montrose |

| Coordinates | 38°34′45″N 107°43′39″W / 38.5791°N 107.7276°W |

| Area | 30,750 acres (124.4 km2)[1] |

| Established | October 21, 1999 |

| Visitors | 357,069 (in 2023)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | nps |

Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park is a national park of the United States located in western Colorado and managed by the National Park Service. The Black Canyon of the Gunnison was established as a national monument on March 2, 1933. It was redesignated a national park on October 21, 1999, and incorporated 4,000 acres owned by the Bureau of Land Management. The Gunnison Gorge National Conservation Area was created at the same time. There are two primary entrances to the park: the south rim entrance is located 15 miles (24 km) east of Montrose, while the north rim entrance is 11 miles (18 km) south of Crawford and is closed in the winter. The park contains 12 miles (19 km) of the 48-mile-long (77 km) Gunnison River. The national park itself contains the deepest and most dramatic section of the canyon, but the canyon continues upstream into Curecanti National Recreation Area and downstream into Gunnison Gorge National Conservation Area. The canyon's name owes itself to the fact that parts of the gorge only receive 33 minutes of sunlight a day, according to Images of America: The Black Canyon of the Gunnison. In the book, author Duane Vandenbusche states, "Several canyons of the American West are longer and some are deeper, but none combines the depth, sheerness, narrowness, darkness, and dread of the Black Canyon."[3]

Geology

The Gunnison River drops an average of 34 feet per mile (6.4 m/km) through the entire canyon, making it the 5th steepest mountain descent in North America. By comparison, the Colorado River drops an average of 7.5 feet per mile (1.42 m/km) through the Grand Canyon. The greatest descent of the Gunnison River occurs within the park at Chasm View dropping 240 feet per mile (45 m/km).[4] The Black Canyon is so named because its steepness makes it difficult for sunlight to penetrate into its depths. As a result, the canyon is often shrouded in shadow, causing the rocky walls to appear black. At its narrowest point the canyon is only 40 ft (12 m) wide at the river.[4][5]

The extreme steepness and depth of the Black Canyon formed as the result of several geologic processes acting together. The Gunnison River is primarily responsible for carving the canyon, though several other geologic events had to occur in order to form the canyon as it is seen today.[6]

Precambrian

The Precambrian gneiss and schist that make up the majority of the steep walls of the Black Canyon formed 1.7 billion years ago during a metamorphic period brought on by the collision of ancient volcanic island arcs with the southern end of what is present-day Wyoming. The lighter-colored pegmatite dikes that can be seen crosscutting the basement rocks formed later during this same period.[7]

Cretaceous - Tertiary

The entire area underwent uplift during the Laramide orogeny between 70 and 40 million years ago which was also part of the Gunnison Uplift. This raised the Precambrian gneiss and schist that makes up the canyon walls. During the Tertiary from 26 to 35 million years ago large episodes of volcanism occurred in the area immediately surrounding the present day Black Canyon. The West Elk Mountains, La Sal Mountains, Henry Mountains, and Abajo Mountains all contributed to burying the area in several thousand feet of volcanic ash and debris.[8]

The modern Gunnison River set its course 15 million years ago as the run-off from the nearby La Sal and West Elk Mountains and the Sawatch Range began carving through the relatively soft volcanic deposits.[8]

Quaternary

With the Gunnison River's course set, a broad uplift in the area 2 to 3 million years ago caused the river to cut through the softer volcanic deposits. Eventually the river reached the Precambrian rocks of the Gunnison Uplift. Since the river was unable to change its course, it began scouring through the extremely hard metamorphic rocks of the Gunnison Uplift. The river's flow was much larger than currently, with much higher levels of turbidity. As a result, the river dug down through the Precambrian gneiss and schist at the rate of 1 inch (25 mm) every 100 years. The extreme hardness of the metamorphic rock along with the relative quickness with which the river carved through them created the steep walls that can be seen today.[8]

A number of feeder canyons running into the Black Canyon slope in the wrong direction for water to flow into the canyon. It is believed that less-entrenched streams in the region shifted to a more north-flowing drainage pattern in response to a change in the tilt of the surrounding terrain. The west-flowing Gunnison, however, was essentially trapped in the hard Precambrian rock of the Black Canyon and could not change its course.[9]

History

The Ute had known the canyon to exist for a long time before the first Europeans saw it. They referred to the river as "much rocks, big water", and are known to have avoided the canyon out of superstition.[3] By the time the United States declared independence in 1776, two Spanish expeditions had passed by the canyons. In the 1800s, the numerous fur trappers searching for beaver pelts would have known of the canyon's existence but they left no written record. The first official account of the Black Canyon was provided by Captain John Williams Gunnison in 1853, who was leading an expedition to survey a route from Saint Louis and San Francisco. He described the country to be "the roughest, most hilly and most cut up" he had ever seen, and skirted the canyon south towards present-day Montrose. Following his death at the hands of the Ute later that year, the river that Captain Gunnison had called the Grand was renamed in his honor.[10]

The Denver & Rio Grande

In 1881, William Jackson Palmer's Denver and Rio Grande Railroad had reached Gunnison from Denver. The line was built to provide a link to the burgeoning gold and silver mines of the San Juan mountains. The rugged terrain precluded using 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1.435 m) standard rail; Palmer decided to go with the narrower 3 ft (0.91 m) gauge. It took over a year for Irish and Italian laborers to carve out a 15-mile (24 km) roadbed from Sapinero to Cimarron, costing a staggering $165,000 per mile. The last mile is said to have cost more than the entire Royal Gorge project.[11]

On August 13, 1882, the first passenger train passed through the Black Canyon. The editor of the Gunnison Review-Press rode in one of the observation cars; he remarked that the canyon was

undoubtedly the largest and most rugged canyon in the world traversed by the iron horse. We had often heard of the scenery of this canyon, but no one can have the faintest conception of its grandeur and magnificence until they have made a trip through it. It is a narrow gorge with walls of granite rising in some places to a height of thousands of feet .... Throughout its entire length there is probably not a quarter of a mile of straight track on it. It is a serpentine road in every respect and the curves are frequent and sharp. In hundreds of places the walls of granite are perpendicular and in many places the road bed is blasted out in the side of the walls of rock which overhang the track.

He went on to proclaim, "Another such a feat of railroad engineering probably can not be found in the world, and there is probably no section of Colorado or of the whole country where such a varied and interesting lot of scenery can be found."[12]

In the hopes of running the railroad through the rest of the Black Canyon, Palmer sent his top engineer Bryan Bryant on an inner canyon exploration. Bryant set off with a 12-man crew in December 1882 expecting to complete the survey in 20 days; he returned in 68. "Eight of the twelve-man crew left after a few days, terrified of the task in front of them. What the rest of the men saw was spectacular and had never been seen by another human." Bryant reported that the Black Canyon was impenetrable, and that it was impossible to build anything in its depths.[13]

Heeding Bryant's advice, Palmer decided to route the railroad south of the canyon and in March 1883, it completed its connection to Salt Lake City and for a brief period the canyon was on the main line of a transcontinental railroad system. While the railroad and early visitors used the canyon as a path to Utah and mines to the southwest, later visitors came to see the canyon as an opportunity for recreation and personal enjoyment.[14]

Rudyard Kipling described his 1889 ride through the canyon in the following words:

We entered a gorge, remote from the sun, where the rocks were two thousand feet sheer, and where a rock splintered river roared and howled ten feet below a track which seemed to have been built on the simple principle of dropping miscellaneous dirt into the river and pinning a few rails a-top. There was a glory and a wonder and a mystery about the mad ride ....[15]

By 1890, an alternate route through Glenwood Springs had been completed and the route through the Black Canyon, being more difficult to operate, lost importance for through trains. However, local rail traffic continued over the "Black Canyon Line" until the route was finally abandoned in the early 1950s.[16][17] Today, various elements of the railroad have been preserved in the Cimarron area including a steel bridge in Cimarron Canyon.[18]

The Gunnison Tunnel

In 1901, the U.S. Geological Survey sent Abraham Lincoln Fellows and William Torrence into the canyon to look for a site to build a diversion tunnel bringing water to the Uncompahgre Valley, which was suffering from water shortages due to an influx of settlers into the area.[19] Torrence, a Montrose native and an expert mountaineer, joined four other men in a failed expedition to explore the canyon in September 1900 using two wooden boats. His experience proved invaluable on the second attempt in August 1901. Torrence and Fellows opted to bring a small specially made multi-chambered rubber raft with a lifeline all the way around it instead of the wooden boats that had doomed the previous journey. The two men entered the canyon on August 12 equipped with "hunting knives, two silk lifeline ropes, and rubber bags to encase their instruments." Torrence and Fellows each had backpacks weighing 35 pounds and the rubber raft turned out to be a great way to float their gear on the narrow river. After 10 days of climbing over rock falls, descending waterfalls, and swimming over 70 sections of the river, they emerged from their 30 mile run with a first recorded descent as well as a suitable tunnel site.[20][21][22][23][24]

Construction on the tunnel began 4 years later, and was fraught with difficulties right from the onset.

Working conditions at the tunnel were difficult due to the high levels of carbon dioxide, excessive temperatures, humidity, water, mud, shale, sand, and a fractured fault zone .... It took the tunneling crew almost one year to bore through 2000 feet of water-filled rock. The tunnel was driven through granite, quartzite, gneiss, and shale as well as layers of sandstone, coal, and limestone. Work on the Gunnison Tunnel was first done manually and by candlelight. One miner would hold the drill and rotate it while the second miner would use a sledgehammer to drive the drill into the rock. This work required strong, hard-working men. In spite of good pay and fringe benefits, most disliked the dangerous underground conditions and stayed an average of only 2 weeks.[25]

26 men were killed during the 4 year undertaking. The tunnel was finally completed in 1909, stretching a distance of 5.8 miles and costing nearly 3 million dollars. At the time, the Gunnison Tunnel held the honor of being the world's longest irrigation tunnel. On September 23, President William Howard Taft dedicated the tunnel in Montrose.[25] The East Portal of the Gunnison Tunnel is accessible via East Portal Road which is on the South Rim of the canyon. Although the tunnel itself is not visible, the diversion dam can be seen from the campground.[26]

Creation of the park

The Black Canyon of the Gunnison was established as a national monument on March 2, 1933. It was redesignated a national park on October 21, 1999,[27] and incorporated 4,000 acres owned by the Bureau of Land Management.[28] The Gunnison Gorge National Conservation Area was created at the same time.

During 1933-35, the Civilian Conservation Corps built the North Rim Road to design by the National Park Service. This includes five miles of roadway and five overlooks; it is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places as a historic district.[29]

About half of the park, 15,599 acres (63.13 km2), was designated a wilderness area in 1976.[30]

The 2,500-acre Sanburg Ranch was added to the park in 2017.[28]

Biology

The Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park contains a wide variety of flora and fauna. Some common plants native to the park include aspen, Ponderosa pine, sagebrush, desert mahogany (Cercocarpus ledifolius), Utah juniper, gambel oak (scrub oak) and single-leaf ash.[31] The Black Canyon gilia (Aliciella penstemonoides) is a species of wildflower native to the park.[32] Wildlife in this park include the pronghorn, black bear, coyote, muskrat, six species of lizard, cougar, raccoon, beaver, elk, river otter, bobcat, and mule deer. In addition, the canyon is the home of a number of resident birds including the American dipper, two species of eagle, eight species of hawk, six species of owl, and Steller's jay as well as migratory birds such as the mountain bluebird, peregrine falcon, magpie, white-throated swift and canyon wren.[33]

Climate

According to the Köppen climate classification system, Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park has a warm-summer humid continental climate (Dfb).

| Climate data for Black Canyon of the Gunnison, Colorado, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 2003–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 55 (13) |

60 (16) |

69 (21) |

80 (27) |

86 (30) |

93 (34) |

97 (36) |

93 (34) |

90 (32) |

80 (27) |

68 (20) |

56 (13) |

97 (36) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 48.7 (9.3) |

53.6 (12.0) |

62.5 (16.9) |

72.6 (22.6) |

79.5 (26.4) |

86.8 (30.4) |

90.9 (32.7) |

88.1 (31.2) |

84.8 (29.3) |

75.1 (23.9) |

63.8 (17.7) |

50.5 (10.3) |

91.4 (33.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 36.8 (2.7) |

39.7 (4.3) |

48.5 (9.2) |

56.1 (13.4) |

66.4 (19.1) |

76.3 (24.6) |

82.1 (27.8) |

80.8 (27.1) |

72.4 (22.4) |

59.9 (15.5) |

46.8 (8.2) |

35.7 (2.1) |

58.5 (14.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 24.8 (−4.0) |

27.8 (−2.3) |

35.7 (2.1) |

42.7 (5.9) |

52.3 (11.3) |

61.3 (16.3) |

67.3 (19.6) |

66.3 (19.1) |

58.4 (14.7) |

46.3 (7.9) |

34.9 (1.6) |

24.4 (−4.2) |

45.2 (7.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 12.9 (−10.6) |

15.9 (−8.9) |

22.9 (−5.1) |

29.3 (−1.5) |

38.3 (3.5) |

46.3 (7.9) |

52.5 (11.4) |

51.9 (11.1) |

44.3 (6.8) |

32.8 (0.4) |

23.1 (−4.9) |

13.1 (−10.5) |

31.9 (−0.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −6.5 (−21.4) |

−4.0 (−20.0) |

3.1 (−16.1) |

11.3 (−11.5) |

22.2 (−5.4) |

32.2 (0.1) |

42.5 (5.8) |

41.9 (5.5) |

28.7 (−1.8) |

12.1 (−11.1) |

2.5 (−16.4) |

−4.9 (−20.5) |

−11.3 (−24.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −22 (−30) |

−24 (−31) |

−10 (−23) |

0 (−18) |

13 (−11) |

25 (−4) |

34 (1) |

32 (0) |

16 (−9) |

−3 (−19) |

−16 (−27) |

−13 (−25) |

−24 (−31) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.73 (44) |

1.74 (44) |

1.99 (51) |

1.84 (47) |

1.59 (40) |

0.73 (19) |

1.65 (42) |

1.69 (43) |

2.08 (53) |

1.90 (48) |

1.49 (38) |

1.52 (39) |

19.95 (507) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 20.2 (51) |

22.2 (56) |

19.0 (48) |

14.2 (36) |

6.6 (17) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.0 (2.5) |

4.8 (12) |

12.0 (30) |

20.3 (52) |

120.7 (305.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.3 | 9.6 | 8.4 | 8.0 | 9.2 | 4.8 | 12.6 | 10.5 | 9.3 | 8.1 | 6.3 | 9.7 | 105.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 9.8 | 9.8 | 7.4 | 5.9 | 2.8 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 2.3 | 6.2 | 10.1 | 54.8 |

| Source: NOAA (mean maxima and minima, precip, snowfall/snow days 2006–2020)[34][35] | |||||||||||||

Attractions

An annual average of about 190,000 tourists visited the park in the period from 2007 to 2016.[2] The main attraction of the park is the scenic drive along US Highway 50 and Colorado Highway 92, as well as the south rim. The east end of the park, where it meets Blue Mesa Reservoir at Blue Mesa Point, is the area most developed for camping. It includes tent camping and RV camping with full hookups (private site), as well as canyon tours, hiking, fishing and boat tours. Nearby is the Curecanti National Recreation Area which includes a visitor center, marina facilities and, among 10 campgrounds within the NRA, the Lake Fork Campground. The west end of the park has river access by automobile, as well as guided tours of the canyon. A short hike at Blue Mesa Point Information Center heads down to Pine Creek and the Morrow Point boat tours, boating, fishing and hiking. At the south rim there is one campground for tent and RV camping, one loop of which has electrical hookups, and several hiking and nature trails. The north rim is also accessible by automobile and has a small, primitive campground. Automobiles can access the river via the East Portal Road at the south rim; this road has a 16% grade and is prohibited to vehicles over 22 feet (7 m) in length.

The river can also be accessed by steep, unmaintained trails called "routes" or "draws" on the north and south rim. These routes require about two hours to hike down and two to four hours to hike back up, depending on which route is taken. All inner canyon descents are strenuous and require Class 3 climbing and basic route finding skills. Steep talus, impassable ledges, and lack of cover are some of the challenges hikers are faced with. Poison ivy also grows abundantly in the draws and on the canyon floor. Long sleeves and hiking boots are strongly recommended. The flow rate of the Gunnison River should also be considered for those planning on camping in the canyon, as high river levels can wash out the camp sites. The National Park Service warns the following: "Routes are difficult to follow, and only individuals in excellent physical condition should attempt these hikes .... Hikers are expected to find their own way and to be prepared for self-rescue."[36] A free back country permit is required for all inner canyon use except at the west end.

The Gunnison River is designated as a Gold Medal Water from 200 yards downstream of Crystal Reservoir Dam to the North Fork. This includes the 12 miles within the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park. Only artificial flies and lures are permitted, and all rainbow trout are catch and release. Additionally, fishing is prohibited within 200 yards downstream of Crystal Dam.[37]

The Black Canyon is a center for rock climbing in a style known as traditional climbing. Most of the climbs are difficult and attempted only by advanced climbers.[38]

Rafting opportunities exist in the region, but the run through the park itself is a difficult technical run for only the best kayakers. There are several impassable stretches of water requiring long, sometimes dangerous portages. The remaining rapids are class III - V, and are only for expert river runners.[39] Downstream, in the Gunnison Gorge National Conservation Area, the river is somewhat easier to navigate, though still very remote and only for experienced runners, with rapids that are Class III - IV.[40][41]

In popular culture

The canyon inspired a 1954 symphonic composition by Frank William Erickson, Black Canyon of the Gunnison.[42] Author Ursula K. Le Guin based the site of the eponymous city in her 1967 novel City of Illusions on the Black Canyon of Gunnison National Park.[43] In 2017, The Infamous Stringdusters released a song about the trip undertaken by Fellows and Torrence, "1901: A Canyon Odyssey".[44][45]

See also

- List of birds of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park

- List of national parks of the United States

References

- ^ "Listing of acreage – December 31, 2011" (XLSX). Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-06. (National Park Service Acreage Reports)

- ^ a b "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2019-03-06.

- ^ a b Vandenbusche, Duane (2009). Images of America - The Black Canyon of the Gunnison. Arcadia Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-7385-6919-2.

- ^ a b "Black Canyon Dimensions". National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ^ "Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park- Things To Know Before You Go". National Park Service. 2006-09-05. Retrieved 2006-10-27.

- ^ "Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park- The Geologic Story". National Park Service. 2006-07-25. Retrieved 2006-10-27.

- ^ Tweto, O (1980). Colorado Geology. Rocky Mountain Association of Geologists. pp. 37–46.

- ^ a b c Trista Thornberry-Ehrlich (2005). "Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park & Curecanti National Recreation Area: Geologic Resource Evaluation Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-11-03. Retrieved 2006-10-27.

- ^ "Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park : From Past to Present". National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ^ "Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park : 1853 - Gunnison Expedition". National Park Service. Retrieved 2014-07-28.

- ^ "Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park : Narrow Gauge Railroad Through the Black Canyon". National Park Service. Retrieved 2014-06-24.

- ^ "Black Canon - The First Passenger Train Through Sunday, August 13, 1882". Gunnison Review-Press. August 14, 1882. p. 1.

- ^ Vandenbusche, Duane (2009). Images of America - The Black Canyon of the Gunnison. Arcadia Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7385-6919-2.

- ^ "BCOTGNP : History & Culture : Animals". National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ^ Kipling, Rudyard (1900). From Sea to Sea, and Other Sketches. Macmillan and Co. ISBN 978-1596058248. Retrieved 2014-07-29.

- ^ Athearn, Robert (1977). The Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-0920-7.

- ^ "DRGW.Net | Black Canyon / Cerro Summit Main Line". www.drgw.net. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- ^ "Historical Sites and Tours | Visit Montrose, CO". www.visitmontrose.com. Archived from the original on 2018-05-14. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- ^ Frank, Jerritt (2003-01-01). "Visions of the landscape : People, place and the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River". University of Montana Scholarworks - Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers. University of Montana: 75–77.

- ^ Vandenbusche, Duane (2009). Images of America - The Black Canyon of the Gunnison. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 35–54. ISBN 978-0-7385-6919-2.

- ^ "Information About Colorado," The Colorado Springs Weekly Gazette, September 5, 1901

- ^ "Through Black Canyon," The Boston Globe, January 20, 1901

- ^ Warner, Mark T., Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monument, Colorado Magazine, May, 1934

- ^ The Incredible Journey, My Magazine, Folder 25, Box 3, Abraham Lincoln Fellows Papers, Yale Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

- ^ a b Clark, David (1994). Uncompahgre Project. Bureau of Reclamation. pp. 6–9.

- ^ "Gunnison Tunnel - Bureau of Reclamation Historic Dams and Water Projects - Managing Water in the West". National Park Service. Archived from the original on March 3, 2015. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- ^ "Cornell University Law School - US Code Collection". US Congress. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ^ a b "National park's 25th anniversary is a milestone for Colorado conservation, compromise". The Denver Post. 2024-10-21. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ Janene Caywood (2005). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: North Rim Road, Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park / North Rim Road Historic District/ 5MN.3522". National Park Service. and accompanying photos

- ^ "Black Canyon of the Gunnison Wilderness". Wilderness Connect. Retrieved 2022-02-02.

- ^ "Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park : Plants". National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ^ Beatty, B.L., W.F. Jennings, and R.C. Rawlinson (2004, February 9). Gilia penstemonoides M.E. Jones (Black Canyon gilia): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region.

- ^ "Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park : Animals". National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ^ "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ "Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park : Hiking the Inner Canyon". National Park Service. Retrieved 2014-07-29.

- ^ Bulger, Amy (2014). "Colorado Parks & Wildlife - 2014 Colorado Fishing". Colorado Parks and Wildlife. p. 21.

- ^ "Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park : Rock Climbing". National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ^ "Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park : Kayaking". National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- ^ "Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park : Rafting". National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- ^ "Gunnison Gorge National Conservation Area". Bureau of Land Management - Colorado. Archived from the original on March 25, 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- ^ Frank Erickson Black Canyon of the Gunnison De Pauw University Band

- ^ Spivack, Charlotte (1984). Ursula K. Le Guin. Boston, MA: Twayne Publishers. p. 21.

- ^ 1901: A Canyon Odyssey - YouTube

- ^ "The Infamous Stringdusters – 1901: A Canyon Odyssey".

External links

- Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park – National Park Service

- Black Canyon of the Gunnison – symphonic poem by Frank Erickson (1923–1996) which has been performed on the rim of the canyon

- 1901: A Canyon Odyssey – song by The Infamous Stringdusters