Bombay Explosion (1944)

Smoke billowing out of the harbour | |

| Date | 14 April 1944 |

|---|---|

| Time | 16:15 IST (10:45 UTC) |

| Location | Victoria Dock, Bombay, British India |

| Coordinates | 18°57′10″N 72°50′42″E / 18.95278°N 72.84500°E |

| Cause | Ship fire |

| Casualties | |

| 800+ dead | |

| 3,000 injured | |

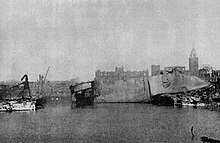

The Bombay explosion (or Bombay docks explosion) occurred on 14 April 1944, in the Victoria Dock of Bombay, British India (now Mumbai, India) when the British freighter SS Fort Stikine caught fire and was destroyed in two giant blasts, scattering debris, sinking surrounding ships and setting fire to the area, killing around 800 to 1,300 people.[1] Some 80,000 people were made homeless[2][3][4] and 71 firemen lost their lives in the aftermath.[5] The ship was carrying a mixed cargo of cotton bales, timber, oil, gold, and ammunition including around 1,400 tons of explosives with an additional 240 tons of torpedoes and weapons.

Vessel, the voyage and cargo

The SS Fort Stikine was a 7,142 gross register ton freighter built in 1942 in Prince Rupert, British Columbia, under a lend-lease agreement; the name Stikine was derived from the Stikine River in British Columbia.

Sailing from Birkenhead on 24 February, via Gibraltar, Port Said and Karachi, she arrived at Bombay on 12 April 1944. Her cargo included 1,395 tons of explosives including 238 tons of sensitive "A" explosives, torpedoes, mines, shells, and munitions. She also carried Supermarine Spitfire fighter aircraft, raw cotton bales, barrels of oil, timber, scrap iron and approximately £890,000 of gold bullion in bars in 31 crates.[6] The 8,700 bales of cotton and lubricating oil were loaded at Karachi and the ship's captain, Alexander James Naismith, recorded his protest about such a "mixture" of cargo.[6] The transportation of cotton through the sea route was inevitable for the merchants, as transporting cotton by rail from Punjab and Sindh to Bombay was banned at that time.[7][why?] Naismith, who lost his life in the explosion, described the cargo as "just about everything that will either burn or blow up."[6]

Incident

In the mid-afternoon around 14:00, the crew were alerted to a fire onboard burning somewhere in the No. 2 hold. The crew, dockside fire teams and fireboats were unable to extinguish the conflagration, despite pumping over 900 tons of water into the ship, and nor were they able to find the source due to the dense smoke. The water was boiling all over the ship, due to heat generated by the fire.[8]

At 15:50 the order to abandon ship was given, and sixteen minutes later there was a great explosion, cutting the ship in two and breaking windows over 12 km (7.5 mi) away. This and a later second explosion were powerful enough to be recorded by seismographs at the Colaba Observatory in the city. Sensors recorded that the earth trembled at Shimla,[9] a city over 1,700 km away. The shower of burning material set fire to neighbourhoods in the area. Around 2 km2 (0.77 sq mi) were set ablaze in an 800 m (870 yd) arc around the ship. Eleven neighbouring vessels had been sunk or were sinking, and the emergency personnel at the site suffered heavy losses. Attempts to fight the fire were dealt a further blow when the second explosion from the ship swept the area at 16:34. Burning cotton bales fell from the sky on docked ships, the dock yard, and neighbourhoods outside the harbour. The sound of explosions was heard as far as 80 km (50 mi) away.[10] Some of the most developed and economically important parts of Bombay were wiped out by the blast and resulting fire.[10]

News

The details of the explosions and losses were first reported to the outside world by the Japanese-controlled Radio Saigon, which gave a detailed report of the incident on 15 April 1944.[11] British-Indian wartime censorship permitted news reporters to send the reports only in the second week of May 1944.[11] Time magazine published the story as late as 22 May 1944 and still it was news to the outside world.[11] A movie depicting the explosions and aftermath, made by Indian cinematographer Sudhish Ghatak, was confiscated by military officers,[6] although parts of it were shown to the public as a newsreel at a later date.[6]

Loss

The total number of lives lost in the explosion is estimated at more than 800, while some estimates put the figure at around 1,300.[12] More than 500 civilians lost their lives, many of them residing in adjoining slum areas, but as it was wartime, information about the full extent of the damage was partially censored.[6] The results of the explosion are summarised as follows:

- Two hundred and thirty-one people killed were attached to various dock services including fire brigade and dock employees.[8]

- Of the above figure, 66 were firemen[13]

- More than 500 civilians were killed[8]

- Some estimates put total deaths at up to 1,300[12]

- More than 2,500 were injured, including civilians[8]

- Thirteen ships were lost[8] and some other ships heavily or partially damaged

- Of the above, three Royal Indian Navy ships were lost[14]

- Thirty-one wooden crates, each containing four gold bars, each gold bar weighing 800 Troy ounces or almost 25 kg.[8] (almost all since recovered)

- More than 50,000 tonnes of shipping destroyed and another 50,000 tonnes of shipping damaged[8]

- Loss of more than 50,000 tonnes of food grains, including rice, which gave rise to black marketing of food grains afterwards.[6]

Suburban relief activities

D. N. Wandrekar, a senior journalist at The Bombay Chronicle newspaper, stated in a report dated 20 April 1944 that Mumbaikars (transl. Residents of Mumbai) are always known for their good heart which is why around five days after the incident massive relief activities were shifted to the suburbs owing to the neutralisation of South Mumbai from the damages caused. Soon after the calamity people from the affected areas began pouring into the suburbs. About six thousand persons from the Mandvi area, mostly middle class, went to Ghatkopar. The workers and others from Ghatkopar got the three schools opened for their accommodation and private households also provided accommodation to these unfortunate families.[citation needed]

There was a rush of labourers from the dock areas who wanted to get out of Bombay on foot by the Agra Road. Ghatkopar workers opened a kitchen for them at the Hindu Sabha Hall. The kitchen served food for about a thousand persons twice daily. The Ghatkopar kitchen was still running when Vile Parle's Irla residents started running a second centre for about 500 persons, where food and lodging were provided for the refugees. A third kitchen was opened at Khotwadi and Narli Agripada in Santacruz where about 300 people were being served. In Khar, arrangements had been made to give rations to about a hundred persons who had found accommodation in Kherwadiand Old Khar village. Khar Danda, a fishing village, had made arrangements for about a hundred people's accommodation and food. Many families on Salsette Island, also known as Mumbai suburb, opened their doors to the needy.[citation needed]

Salvage

As part of the salvage operation, sub-lieutenant Ken Jackson, RNVR was seconded to the Indian government to establish the pumping operation. He and chief petty officer Charles Brazier arrived in Bombay on 7 May 1944. Over a period of three months, many ships were salvaged. The de-watering operation took three months to complete, after which Jackson and Brazier returned to their base in Colombo. Jackson remained in the Far East for another two years, conducting further salvage work. For their efforts with the pumping operation, both men were rewarded: Brazier was awarded the MBE, and Jackson received an accelerated promotion. An Australian minesweeper, HMAS Gawler, landed working parties on 21 June 1944, to assist in the restoration of the port.[14]

Aftermath

It took three days to bring the fire under control, and later, 8,000 men toiled for seven months to remove around 500,000 tons of debris and bring the docks back into action.

The inquiry into the explosion identified the cotton bales as probably being the seat of the fire. It was critical of several errors:

- Storing the cotton below the munitions

- Not displaying the red flag (B flag) required to indicate a "dangerous cargo on board"

- Delaying unloading the explosives

- Not using steam injectors to contain the fire

- A delay in alerting the local fire brigade[15]

Many families lost all their belongings and were left with just the clothes on their backs. Thousands became destitute. It was estimated that about 6,000 firms were affected, and 50,000 people lost their jobs.[6] The government took full responsibility for the disaster, and monetary compensation was paid to citizens who made a claim for loss or damage to property.

During periodic dredging operations to maintain the depth of the docking bays, many intact gold bars have been found, some as late as February 2011, and returned to the government. A live shell weighing 45 kg (100 lb) was also found in October 2011.[16] The Mumbai Fire Brigade's headquarters at Byculla has a memorial to the fire fighters who died. National Fire Safety Week is observed across India[17] from 14 to 21 April, in memory of the 66 firemen who died in this explosion.[13]

Ships lost or severely damaged

Apart from Fort Stikine, the following vessels were sunk or severely damaged.

| Ship | Flag or operator | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Baroda | Baroda was a 3,172 GRT cargo liner owned by the British India Steam Navigation Company.[18] The vessel was burnt out.[19] | |

| HMHS Chantilly | Chantilly was a 10,017 GRT hospital ship that was formerly a French passenger ship. She was repaired and was returned to her French owners after the war.[20] | |

| HMIS El Hind | El Hind was a 5,319 GRT passenger ship used by The Scindia Steam Navigation Company Ltd. for the conveyance of pilgrims. She had been requisitioned by the Royal Indian Navy as a Landing Ship Infantry (Large). She caught fire and sank.[21][22] | |

| Empire Indus | Empire Indus was a 5,155 GRT cargo ship. She was severely damaged by the explosion but was repaired, returning to service in November 1945.[23] | |

| Fort Crevier | Fort Crevier was a 7,142 GRT Fort ship. She was burnt out and declared a constructive total loss. The vessel was used as a hulk until 1948, when she was scrapped.[19][24] | |

| Generaal van der Heyden | Generaal van der Heyden was a 1,213 GRT cargo ship of the Koninklijke Paketvaart-Maatschappij. She caught fire and sank, with the loss of 15 of her crew.[25] | |

| Generaal van Sweiten | Generaal van Sweiten was a 1,300 GRT cargo ship of the Koninklijke Paketvaart-Maatschappij. She caught fire and sank, with the loss of 2 crew.[25] | |

| Graciosa | Graciosa was a 1,173 GRT cargo ship owned by Skibs A/S Fjeld and operated under the management of Hans Kiær & Co. She was severely damaged and was sold for scrap in July 1944.[26] | |

| Iran | Iran was a 5,677 GRT Standard World War I cargo ship operated by the Iran Steamship Company under the management of Wallem & Co. Ltd. She was severely damaged and was scrapped.[27] | |

| Jalapadma | Jalapadma was a 3,857 GRT cargo ship of the Scindia Steam Navigation Company. She was pushed on shore and later scrapped.[28] | |

| Kingyuan | Kingyuan was a 2,653 GRT cargo ship of the China Navigation Company. She caught fire and sank.[29] | |

| HMS LCP 323 | The landing craft was sunk.[30] | |

| HMS LCP 866 | The landing craft was sunk.[30] | |

| Norse Trader | Norse Trader was a 3,507 GRT cargo ship owned by Wallem & Co., Hong Kong. While there were no casualties, the ship was a total loss and was broken up.[31] | |

| Rod El Farag | Rod El Farag was a 6,292 GRT cargo liner of the Sociète Misr de Navigation Maritime. She was gutted by fire.[32] Declared a total loss, she was sunk for use as a jetty.[33] | |

| Tinombo | Tinombo was a 872 GRT coaster owned by the Koninklijke Packetvaart Maatschappij. She was heavily damaged, and sank with the loss of 8 crew.[29] |

See also

- Explosion of the RFA Bedenham

- Halifax Explosion

- List of accidents and incidents involving transport or storage of ammunition

- List of the largest artificial non-nuclear explosions

References

Citations

- ^ "Explosion on cargo ship rocks Bombay, India – Apr 14, 1944". History.com. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ "Has India's contribution to WW2 been ignored?". BBC News. 16 June 2015. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ Bombay Explosion Archived 14 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine A Corporal's War: World War II Adventures of a Royal Engineer, p. 233

- ^ The Day It Rained Gold Bricks and a Horse Ran Headless Archived 14 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine Bombay, Meri Jaan: Writings on Mumbai Page 138

- ^ "That's how Mumbai's fire brigade Rolls". Mumbai Mirror. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Times News Network (11 April 2004). "When Bombay docks rocked". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Ennis, John. p. 25

- ^ Ennis, John. p. 84

- ^ a b "War Explodes into Bombay". Life. 22 May 1944. pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b c "India: Fire in Bombay". Time magazine. 22 May 1944. Archived from the original on 14 December 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Explosion on Corgo ship rocks Bombay, India". History.com. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Tributes paid to firemen". The Hindu. 15 April 2011. Archived from the original on 20 April 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ a b "On this day: 1944". Naval Historical Society of Australia. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ The Times, Tuesday, 12 September 1944; pg. 3; Issue 49956; col E

- ^ Tiwary, Deeptiman (24 October 2011). "Live, 45-kg shell dredged from WW-II ship's ruins". Mumbai Mirror. Archived from the original on 30 December 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ^ "Fire Safety Week". National Safety Council (India). 17 February 2014. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ "SS Baroda". Clydeships. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Convoy PB.74". Convoyweb. Archived from the original on 4 September 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ "HMHS Chantilly (1941)". Maritime Quest. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ "SS El Hind". Clydeships. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ "Landing Ship Infantry HMIS El Hind". Uboat. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ Mitchell, W. H.; Sawyer, L. A. (1995). The Empire Ships. London, New York, Hamburg, Hong Kong: Lloyd's of London Press Ltd. p. not cited. ISBN 1-85044-275-4.

- ^ "Fort Ships A – J". Mariners. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij 1888–1967". The Ships List. Archived from the original on 22 July 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ "D/S Graciosa". Warsailors. Archived from the original on 2 September 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ "Waikawa". Tynebuilt. Archived from the original on 31 May 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ "Scindia Steam Navigation Co". The Ships List. Archived from the original on 22 July 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Ships Lost in the WWII Bombay Explosion". Merchantships. Archived from the original on 4 September 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ a b Rohwer, Jürgen; Gerhard Hümmelchen. "Seekrieg 1944, April". Württembergische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart (in German). Archived from the original on 29 October 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ "Norwegian Merchant Fleet 1939–1945 . Ships starting with N – Nors". Warsailors. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ "SS Chindwin". Clydeships. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ Jordan, Roger (1999). The world's merchant fleets, 1939. London: Chatham publishing. p. 452. ISBN 1-86176-023-X.

General and cited references

- Ennis, John (1959). The Great Bombay Explosion. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce. LCCN 59-12241. OCLC 1262947 – via the Internet Archive. The Great Bombay Explosion at Google Books.