Cambridge, Mass.

Cambridge | |

|---|---|

| Motto(s): | |

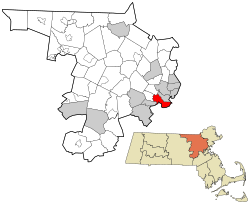

Location of Cambridge in Middlesex County, Massachusetts | |

| Coordinates: 42°22′25″N 71°06′38″W / 42.37361°N 71.11056°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Middlesex |

| Region | New England |

| Settled | 1630 |

| Incorporated | 1636 |

| City | 1846 |

| Named for | University of Cambridge |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Mayor | E. Denise Simmons[2] |

| • Vice mayor | Marc C. McGovern |

| • City manager | Yi-An Huang |

| Area | |

• Total | 7.10 sq mi (18.40 km2) |

| • Land | 6.40 sq mi (16.57 km2) |

| • Water | 0.71 sq mi (1.83 km2) |

| Elevation | 40 ft (12 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 118,403 |

| • Density | 18,512.04/sq mi (7,147.01/km2) |

| • Demonym | Cantabrigian |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Code | 02138-02142 |

| Area code | 617 / 857 |

| FIPS code | 25-11000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0617365 |

| Website | cambridgema |

Cambridge (/ˈkeɪmbrɪdʒ/[4] KAYM-brij) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. It is a suburb in the Greater Boston metropolitan area, located directly across the Charles River from Boston. The city's population as of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the most populous city in the county, the fourth-largest in Massachusetts behind Boston, Worcester, and Springfield, and ninth-most populous in New England.[5] The city was named in honor of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England, which was an important center of the Puritan theology that was embraced by the town's founders.[6]: 18

Harvard University, an Ivy League university founded in Cambridge in 1636, is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States. Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Lesley University, and Hult International Business School also are based in Cambridge.[7] Radcliffe College, a women's liberal arts college, was based in Cambridge from its 1879 founding until its assimilation into Harvard in 1999.

Kendall Square, near MIT in the eastern part of Cambridge, has been called "the most innovative square mile on the planet" due to the high concentration of startup companies that have emerged there since 2010.[8]

Founded in December 1630 during the colonial era, Cambridge was one among the first cities established in the Thirteen Colonies, and it went on to play a historic role during the American Revolution.

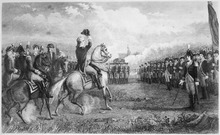

In May 1775, approximately 16,000 American patriots assembled in Cambridge Common to begin organizing a military retaliation against British troops following the Battles of Lexington and Concord. On July 2, 1775, two weeks after the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia formally established the Continental Army and appointed George Washington commander of it, Washington arrived at Cambridge Common to take command of the Patriot soldiers camped there. Many of these soldiers played a role in supporting Washington's successful Siege of Boston, which trapped garrisoned British troops from moving by land, forcing the British to ultimately abandon Boston. Cambridge Common is thus celebrated as the birthplace of the Continental Army.[9][10]

History

Pre-colonization

The Massachusett inhabited the area that is now called Cambridge for thousands of years prior to European colonization of the Americas, most recently under the name Anmoughcawgen, which means 'fishing weir' or 'beaver dam' in Natick.[11] At the time of European contact, the area was inhabited by Naumkeag or Pawtucket to the north and Massachusett to the south, and may have been inhabited by other groups such as the Totant, not well described in later European narratives.[12] The contact period introduced a number of European infectious diseases which would decimate native populations in virgin soil epidemics, leaving the area uncontested upon the arrival of large groups of English settlers in 1630.

17th century and colonialism

In December 1630, the site of present-day Cambridge was chosen for settlement because it was safely upriver from Boston Harbor, making it easily defensible from attacks by enemy ships. The city was founded by Thomas Dudley, his daughter Anne Bradstreet, and his son-in-law Simon Bradstreet. The first houses were built in the spring of 1631. The settlement was initially referred to as "the newe towne".[13][14] Official Massachusetts records show the name rendered as Newe Towne by 1632, and as Newtowne by 1638.[14][15]

Located at the first convenient Charles River crossing west of Boston, Newtowne was one of several towns, including Boston, Dorchester, Watertown, and Weymouth, founded by the 700 original Puritan colonists of the Massachusetts Bay Colony under Governor John Winthrop. Its first preacher was Thomas Hooker, who led many of its original inhabitants west in 1636 to found Hartford and the Connecticut Colony; before leaving, they sold their plots to more recent immigrants from England.[13] The original village site is now within Harvard Square. The marketplace where farmers sold crops from surrounding towns at the edge of a salt marsh (since filled) remains within a small park at the corner of John F. Kennedy and Winthrop Streets.

In 1636, Newe College, later renamed Harvard College after benefactor John Harvard, was founded as North America's first institution of higher learning. Its initial purpose was training ministers. According to Cotton Mather, Newtowne was chosen for the site of the college by the Great and General Court, then the legislature of Massachusetts Bay Colony, primarily for its proximity to the popular and highly respected Puritan preacher Thomas Shepard. In May 1638,[16] the settlement's name was changed to Cambridge in honor of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England.[13][17]

In 1639, the Massachusetts General Court purchased the land that became present-day Cambridge from the Naumkeag Squaw Sachem of Mistick.[18][19]

The town comprised a much larger area than the present city,[13] with various outlying parts becoming independent towns over the years: Cambridge Village (later Newtown and now Newton) in 1688,[20] Cambridge Farms (now Lexington) in 1712[13] or 1713,[21] and Little or South Cambridge (now Brighton)[a] and Menotomy or West Cambridge (now Arlington) in 1807.[13][22][b] In the late 19th century, various schemes for annexing Cambridge to Boston were pursued and rejected.[23]

Newtowne's ministers, Hooker and Shepard, the college's first president, the college's major benefactor, and the first schoolmaster Nathaniel Eaton were all Cambridge alumni, as was the colony's governor John Winthrop. In 1629, Winthrop had led the signing of the founding document of the city of Boston, which was known as the Cambridge Agreement, after the university.[24] In 1650, Governor Thomas Dudley signed the charter creating the corporation that still governs Harvard College.[25]

Cambridge grew slowly as an agricultural village eight miles (13 km) by road from Boston, the colony's capital. By the American Revolution, most residents lived near the Common and Harvard College, with most of the town comprising farms and estates. Most inhabitants were descendants of the original Puritan colonists, but there was also a small elite of Anglican "worthies" who were not involved in village life, made their livings from estates, investments, and trade, and lived in mansions along "the Road to Watertown", present-day Brattle Street, which is still known as Tory Row.

18th century and Revolutionary War

The Virginian George Washington, coming from Philadelphia, took command of the force of Patriot soldiers camped on Cambridge Common on July 3, 1775, which is now considered the birthplace of the Continental Army.[13][c]

On January 24, 1776, Henry Knox arrived with an artillery train captured from Fort Ticonderoga, which allowed Washington to force the British Army to evacuate Boston. Most of the Loyalist estates in Cambridge were confiscated after the Revolutionary War.

19th century and industrialization

Between 1790 and 1840, Cambridge grew rapidly with the construction of West Boston Bridge in 1792 connecting Cambridge directly to Boston, making it no longer necessary to travel eight miles (13 km) through the Boston Neck, Roxbury, and Brookline to cross the Charles River. A second bridge, the Canal Bridge, opened in 1809 alongside the new Middlesex Canal. The new bridges and roads made what were formerly estates and marshland into prime industrial and residential districts.

In the mid-19th century, Cambridge was the center of a literary revolution. It was home to some of the famous Fireside poets, named because their poems would often be read aloud by families in front of their evening fires. The Fireside poets, including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, and Oliver Wendell Holmes, were highly popular and influential in this era.

Soon after, turnpikes were built: the Cambridge and Concord Turnpike (today's Broadway and Concord Ave.), the Middlesex Turnpike (Hampshire St. and Massachusetts Ave. northwest of Porter Square), and what are today's Cambridge, Main, and Harvard Streets connected various areas of Cambridge to the bridges. In addition, the town was connected to the Boston & Maine Railroad,[26] leading to the development of Porter Square as well as the creation of neighboring Somerville from the formerly rural parts of Charlestown.

Cambridge was incorporated as a city in 1846.[13] The city's commercial center began to shift from Harvard Square to Central Square, which became the city's downtown around that time.

Between 1850 and 1900, Cambridge took on much of its present character, featuring streetcar suburban development along the turnpikes and working class and industrial neighborhoods focused on East Cambridge, comfortable middle-class housing on the old Cambridgeport, and Mid-Cambridge estates and upper-class enclaves near Harvard University and on the minor hills. The arrival of the railroad in North Cambridge and Northwest Cambridge led to three changes: the development of massive brickyards and brickworks between Massachusetts Avenue, Concord Avenue, and Alewife Brook; the ice-cutting industry launched by Frederic Tudor on Fresh Pond; and the carving up of the last estates into residential subdivisions to house the thousands of immigrants who arrived to work in the new industries.

For much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the city's largest employer was the New England Glass Company, founded in 1818. By the middle of the 19th century, it was the world's largest and most modern glassworks. In 1888, Edward Drummond Libbey moved all production to Toledo, Ohio, where it continues today under the name Owens-Illinois. The company's flint glassware with heavy lead content is prized by antique glass collectors, and the Toledo Museum of Art has a large collection. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Sandwich Glass Museum on Cape Cod also house several pieces.

In 1895, Edwin Ginn, founder of Ginn and Company, built the Athenaeum Press Building for his publishing textbook empire.

20th century

By 1920, Cambridge was one of New England's main industrial cities, with nearly 120,000 residents. Among the largest businesses in Cambridge during the period of industrialization was Carter's Ink Company, whose neon sign long adorned the Charles River and which was for many years the world's largest ink manufacturer. Next door was the Athenaeum Press. Confectionery and snack manufacturers in the Cambridgeport-Area 4-Kendall corridor included Kennedy Biscuit Factory, later part of Nabisco and originator of the Fig Newton,[27] Necco, Squirrel Brands,[28] George Close Company (1861–1930s),[29] Page & Shaw, Daggett Chocolate (1892–1960s, recipes bought by Necco),[30] Fox Cross Company (1920–1980, originator of the Charleston Chew, and now part of Tootsie Roll Industries),[31] Kendall Confectionery Company, and James O. Welch (1927–1963, originator of Junior Mints, Sugar Daddies, Sugar Mamas, and Sugar Babies, now part of Tootsie Roll Industries).[32] Main Street was nicknamed "Confectioner's Row".[33]

Only the Cambridge Brands subsidiary of Tootsie Roll Industries remains in town, still manufacturing Junior Mints in the old Welch factory on Main Street.[32] The Blake and Knowles Steam Pump Company (1886), the Kendall Boiler and Tank Company (1880, now in Chelmsford, Massachusetts), and the New England Glass Company (1818–1878) were among the industrial manufacturers in what are now Kendall Square and East Cambridge.

In 1935, the Cambridge Housing Authority and the Public Works Administration demolished an integrated low-income tenement neighborhood with African Americans and European immigrants. In its place, it built the whites-only "Newtowne Court" public housing development and the adjoining, blacks-only "Washington Elms" project in 1940; the city required segregation in its other public housing projects as well.[34][35][36]

As industry in New England began to decline during the Great Depression and after World War II, Cambridge lost much of its industrial base. It also began to become an intellectual, rather than an industrial, center. Harvard University, which had always been important as both a landowner and an institution, began to play a more dominant role in the city's life and culture. When Radcliffe College was established in 1879, the town became a mecca for some of the nation's most academically talented female students. MIT's move from Boston to Cambridge in 1916 reinforced Cambridge's status as an intellectual center of the United States.

After the 1950s, the city's population began to decline slowly as families tended to be replaced by single people and young couples. In Cambridge Highlands, the technology company Bolt, Beranek, & Newman produced the first network router in 1969 and hosted the invention of computer-to-computer email in 1971. The 1980s brought a wave of high technology startups. Those selling advanced minicomputers were overtaken by the microcomputer.[citation needed][37] Cambridge-based VisiCorp made the first spreadsheet software for personal computers, VisiCalc, and helped propel the Apple II to consumer success. It was overtaken and purchased by Cambridge-based Lotus Development, maker of Lotus 1-2-3 (which was, in turn, replaced in by Microsoft Excel).

The city continues to be home to many startups. Kendall Square was a software hub through the dot-com boom and today hosts offices of such technology companies as Google, Microsoft, and Amazon. The Square also now houses the headquarters of Akamai.[38]

In 1976, Harvard's plans to start experiments with recombinant DNA led to a three-month moratorium and a citizen review panel. In the end, Cambridge decided to allow such experiments but passed safety regulations in 1977. This led to regulatory certainty and acceptance when Biogen opened a lab in 1982, in contrast to the hostility that caused the Genetic Institute, a Harvard spinoff, to abandon Somerville and Boston for Cambridge.[39] The biotech and pharmaceutical industries have since thrived in Cambridge, which now includes headquarters for Biogen and Genzyme; laboratories for Novartis, Teva, Takeda, Alnylam, Ironwood, Catabasis, Moderna Therapeutics, Editas Medicine; support companies such as Cytel; and many smaller companies.

Rent control

During the era of rent control in Massachusetts, at least 20 percent of all rent controlled apartments in Cambridge housed the rich.[40] The vast majority housed middle- and high-income earners.[40] In an independent study conducted of 2/3 of the rent controlled apartments in Cambridge in 1988, 246 were households headed by doctors, 298 by lawyers, 265 by architects, 259 by professors, and 220 by engineers. There were 2,650 with students, including 1,503 with graduate students.[40]

Those who lived in rent controlled apartments included

- Ruth Abrams, a Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.[40]

- Kenneth Reeves, the mayor of Cambridge at the time rent control was repealed in Massachusetts, was living in the same rent controlled apartment he lived in as a Harvard student in 1973.[40]

- Frederik, Crown Prince of Denmark[41][40]

The end of rent control in 1994 had numerous effects on the city. Within four years of repealing the law, Cambridge, where "the city's form of rent control was unusually strict," saw new housing and construction increase by 50%, and the tax revenue from construction permits tripled.[41] Property values in Cambridge increased by about $7.8 billion in the decade following the repeal.[42] Roughly a quarter of this increase, $1.8 billion ($3 billion in 2024 dollars), was due to the repeal of rent control.[42]

Close to 40% of all Cambridge properties were under rent control when it was repealed.[42] Their property values appreciated faster than non-rent controlled properties, as did the properties around them.[43] By the end of the 20th century, Cambridge had one of the most costly housing markets in the Northeastern United States.[44]

21st century

Cambridge's mix of amenities and proximity to Boston kept housing prices relatively stable despite the bursting of the United States housing bubble in 2008 and 2009.[45] Cambridge has been a sanctuary city since 1985 and reaffirmed its status as such in 2006.[46]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Cambridge has a total area of 7.1 square miles (18 km2), 6.4 square miles (17 km2) of which is land and 0.7 square miles (1.8 km2) (9.82%) of which is water.

Adjacent municipalities

Cambridge is located in eastern Massachusetts, bordered by:

- the city of Boston to the south and east (across the Charles River)

- the city of Somerville to the north

- the town of Arlington to the northwest

- the town of Belmont and

- the city of Watertown to the west

The border between Cambridge and the neighboring city of Somerville passes through densely populated neighborhoods, which are connected by the MBTA Red Line. Some of the main squares, Inman, Porter, and to a lesser extent, Harvard and Lechmere, are very close to the city line, as are Somerville's Union and Davis Squares.

Through the City of Cambridge's exclusive municipal water system, the city further controls two exclave areas, one being Payson Park Reservoir and Gatehouse, a 2009 listed American Water Landmark located roughly one mile west of Fresh Pond and surrounded by the town of Belmont. The second area is the larger Hobbs Brook and Stony Brook watersheds, which share borders with neighboring towns and cities including Lexington, Lincoln, Waltham and Weston.

Neighborhoods

Squares

Cambridge has been called the "City of Squares",[47] as most of its commercial districts are major street intersections known as squares. Each square acts as a neighborhood center.

Kendall Square, formed by the junction of Broadway, Main Street, and Third Street, has been called "the most innovative square mile on the planet", owing to its high concentration of entrepreneurial start-ups and quality of innovation which have emerged in the vicinity of the square since 2010.[8][48] Technology Square is an office and laboratory building cluster in this neighborhood. Just over the Longfellow Bridge from Boston, at the eastern end of the MIT campus, it is served by the Kendall/MIT station on the MBTA Red Line subway. Most of Cambridge's large office towers are located in the Square. Kendall Square houses some of the biggest technological companies of the world, including Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, and Apple. A biotech industry has developed in this area. The Cambridge Innovation Center, a large co-working space, is in Kendall Square at 1 Broadway. The Cambridge Center office complex is in Kendall Square, and not at the actual center of Cambridge. The "One Kendall Square" complex is nearby, but not actually in Kendall Square.

Central Square is formed by the junction of Massachusetts Avenue, Prospect Street, and Western Avenue.[49]: 1 Containing a variety of ethnic restaurants, it was economically depressed as recently as the late 1990s; it underwent gentrification in recent years (in conjunction with the development of the nearby University Park at MIT), and continues to grow more costly.[50] It is served by the Central Station stop on the MBTA Red Line subway.[49]: 1–2 Lafayette Square, formed by the junction of Massachusetts Avenue, Columbia Street, Sidney Street, and Main Street, is considered part of the Central Square area. Cambridgeport is south of Central Square, and bordered by MIT, the Charles River, Massachusetts Avenue, and River Street.[51]

Harvard Square is formed by the junction of Massachusetts Avenue, Brattle Street, Dunster Street, and JFK Street.[52] This is the primary site of Harvard University and a major Cambridge shopping area.[52] It is served by a Red Line station.[53] Harvard Square was originally the Red Line's northwestern terminus and a major transfer point to streetcars that also operated in a short tunnel—which is still a major bus terminal, although the area under the Square was reconfigured dramatically in the 1980s when the Red Line was extended.[54] A short distance away from the square lies the Cambridge Common, while the neighborhood north of Harvard and east of Massachusetts Avenue is known as Baldwin, in honor of the first Black principal of Cambridge public schools, Maria L. Baldwin. It was renamed "Baldwin" in 2021, and so some know the area better by its former name, Agassiz, after the famed scientist Louis Agassiz.[55][56][57]

Porter Square is about a mile north on Massachusetts Avenue from Harvard Square, at the junction of Massachusetts and Somerville Avenues.[58] It includes part of the city of Somerville[59] and is served by the Porter Square Station, a complex housing a Red Line stop and a Fitchburg Line commuter rail stop.[60] Lesley University's University Hall and Porter campus are in Porter Square.[59]

Inman Square is at the junction of Cambridge and Hampshire streets in mid-Cambridge.[61] It is home to restaurants, bars, music venues, and boutiques.[61] Victorian streetlights, benches, and bus stops were added to the streets in the 2000s, and a new city park was installed.[citation needed]

Lechmere Square is at the junction of Cambridge and First streets, adjacent to the CambridgeSide Galleria shopping mall. It is served by Lechmere station on the MBTA Green Line.[62]

Other neighborhoods

The City of Cambridge officially recognizes 13 neighborhoods, which are as follows:

- East Cambridge (Area 1) is bordered on the north by Somerville, on the east by the Charles River, on the south by Broadway and Main Street, and on the west by the Grand Junction Railroad tracks. It includes the NorthPoint development.

- MIT Campus (Area 2) is bordered on the north by Broadway, on the south and east by the Charles River, and on the west by the Grand Junction Railroad tracks.

- Wellington-Harrington (Area 3) is bordered on the north by Somerville, on the south and west by Hampshire Street, and on the east by the Grand Junction Railroad tracks.

- The Port, formerly known as Area 4, is bordered on the north by Hampshire Street, on the south by Massachusetts Avenue, on the west by Prospect Street, and on the east by the Grand Junction Railroad tracks. Residents of Area 4 often simply call their neighborhood "The Port" and the area of Cambridgeport and Riverside "The Coast". In October 2015, the Cambridge City Council officially renamed Area 4 "The Port", formalizing the longtime nickname, largely on the initiative of neighborhood native and then-Vice Mayor Dennis Benzan. The port is usually the busier part of the city.[63]

- Cambridgeport (Area 5) is bordered on the north by Massachusetts Avenue, on the south by the Charles River, on the west by River Street, and on the east by the Grand Junction Railroad tracks.

- Mid-Cambridge (Area 6) is bordered on the north by Kirkland and Hampshire Streets and Somerville, on the south by Massachusetts Avenue, on the west by Peabody Street, and on the east by Prospect Street.

- Riverside (Area 7), an area sometimes called "The Coast", is bordered on the north by Massachusetts Avenue, on the south by the Charles River, on the west by JFK Street, and on the east by River Street.

- Baldwin (Area 8) is bordered on the north by Somerville, on the south and east by Kirkland Street, and on the west by Massachusetts Avenue.

- Neighborhood Nine or Radcliffe (formerly called Peabody, until the recent relocation of a neighborhood school by that name) is bordered on the north by railroad tracks, on the south by Concord Avenue, on the west by railroad tracks, and on the east by Massachusetts Avenue.

- The Avon Hill sub-neighborhood consists of the higher elevations within the area bounded by Upland Road, Raymond Street, Linnaean Street and Massachusetts Avenue.

- Brattle area/West Cambridge (Area 10) is bordered on the north by Concord Avenue and Garden Street, on the south by the Charles River and Watertown, on the west by Fresh Pond and the Collins Branch Library, and on the east by JFK Street. It includes the sub-neighborhoods of Brattle Street (formerly known as Tory Row) and Huron Village.

- North Cambridge (Area 11) is bordered on the north by Arlington and Somerville, on the south by railroad tracks, on the west by Belmont, and on the east by Somerville.

- Cambridge Highlands (Area 12) is bordered on the north and east by railroad tracks, on the south by Fresh Pond, and on the west by Belmont.

- Strawberry Hill (Area 13) is bordered on the north by Fresh Pond, on the south by Watertown, on the west by Belmont, and on the east by the Watertown-Cambridge Greenway (formerly railroad tracks).

Gallery

- Areas of Cambridge

Climate

In the Köppen-Geiger classification, Cambridge has a hot-summer humid continental climate (Dfa) with hot summers and cold winters, that can appear in the southern end of New England's interior. Abundant rain falls on the city (and in the winter often as snow); it has no dry season. The average January temperature is 26.6 °F (−3 °C), making Cambridge part of Group D, independent of the isotherm. There are four well-defined seasons.[64]

| Climate data for Cambridge, 1991–2020 simulated normals (16 ft elevation) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 37.0 (2.8) |

39.2 (4.0) |

45.9 (7.7) |

57.6 (14.2) |

67.5 (19.7) |

76.6 (24.8) |

82.6 (28.1) |

81.3 (27.4) |

74.1 (23.4) |

62.8 (17.1) |

52.3 (11.3) |

42.4 (5.8) |

59.9 (15.5) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 28.8 (−1.8) |

30.6 (−0.8) |

37.4 (3.0) |

48.2 (9.0) |

58.1 (14.5) |

67.5 (19.7) |

73.4 (23.0) |

72.1 (22.3) |

64.9 (18.3) |

53.6 (12.0) |

43.7 (6.5) |

34.5 (1.4) |

51.1 (10.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 20.5 (−6.4) |

21.9 (−5.6) |

28.9 (−1.7) |

39.0 (3.9) |

48.7 (9.3) |

58.3 (14.6) |

64.2 (17.9) |

63.0 (17.2) |

55.8 (13.2) |

44.4 (6.9) |

35.1 (1.7) |

26.8 (−2.9) |

42.2 (5.7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.72 (94) |

3.74 (95) |

4.52 (115) |

4.37 (111) |

3.66 (93) |

4.38 (111) |

3.46 (88) |

3.72 (94) |

3.92 (100) |

4.78 (121) |

4.05 (103) |

4.97 (126) |

49.29 (1,251) |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 18.5 (−7.5) |

19.2 (−7.1) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

34.2 (1.2) |

45.7 (7.6) |

56.3 (13.5) |

62.4 (16.9) |

61.7 (16.5) |

55.8 (13.2) |

44.4 (6.9) |

33.6 (0.9) |

25.0 (−3.9) |

40.1 (4.5) |

| Source 1: PRISM Climate Group[65] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NCEI(Precipitation)[66] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1764 | 1,582 | — |

| 1790 | 2,115 | +33.7% |

| 1800 | 2,453 | +16.0% |

| 1810 | 2,323 | −5.3% |

| 1820 | 3,295 | +41.8% |

| 1830 | 6,072 | +84.3% |

| 1840 | 8,409 | +38.5% |

| 1850 | 15,215 | +80.9% |

| 1860 | 26,060 | +71.3% |

| 1870 | 39,634 | +52.1% |

| 1880 | 52,669 | +32.9% |

| 1890 | 70,028 | +33.0% |

| 1900 | 91,886 | +31.2% |

| 1910 | 104,839 | +14.1% |

| 1920 | 109,694 | +4.6% |

| 1930 | 113,643 | +3.6% |

| 1940 | 110,879 | −2.4% |

| 1950 | 120,740 | +8.9% |

| 1960 | 107,716 | −10.8% |

| 1970 | 100,361 | −6.8% |

| 1980 | 95,322 | −5.0% |

| 1990 | 95,802 | +0.5% |

| 2000 | 101,355 | +5.8% |

| 2010 | 105,162 | +3.8% |

| 2020 | 118,403 | +12.6% |

| 2023 | 118,214 | −0.2% |

Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79] Source: U.S. Decennial Census[80] | ||

| Historical racial composition | 2020[81] | 2010[82] | 1990[83] | 1970[83] | 1950[83] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 61.7% | 66.6% | 75.3% | 91.1% | 95.3% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 57.5% | 62.1% | 71.6% | 89.7%[84] | n/a |

| Black or African American | 10.6% | 11.7% | 13.5% | 6.8% | 4.3% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 8.8% | 7.6% | 6.8% | 1.9%[84] | n/a |

| Asian | 18.3% | 15.1% | 8.4% | 1.5% | 0.3% |

| Two or more races | 7.1% | 4.3% | n/a | n/a | n/a |

2020 census

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[85] | Pop 2010[86] | Pop 2020[87] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 65,425 | 65,259 | 65,553 | 64.55% | 62.06% | 55.36% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 11,627 | 11,589 | 12,016 | 11.47% | 11.02% | 10.15% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 213 | 159 | 154 | 0.21% | 0.15% | 0.13% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 11,984 | 15,818 | 22,628 | 11.82% | 15.04% | 19.11% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 71 | 31 | 49 | 0.07% | 0.03% | 0.04% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 713 | 575 | 993 | 0.70% | 0.55% | 0.84% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 3,867 | 3,757 | 6,272 | 3.82% | 3.57% | 5.30% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 7,455 | 7,974 | 10,738 | 7.36% | 7.58% | 9.07% |

| Total | 101,355 | 105,162 | 118,403 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the census[88] of 2010, there were 105,162 people, 44,032 households, and 17,420 families residing in the city. The population density was 16,354.9 inhabitants per square mile (6,314.7/km2). There were 47,291 housing units at an average density of 7,354.7 per square mile (2,839.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 66.60% White, 11.70% Black or African American, 0.20% Native American, 15.10% Asian (3.7% Chinese, 1.4% Asian Indian, 1.2% Korean, 1.0% Japanese[89]), 0.01% Pacific Islander, 2.10% from other races, and 4.30% from two or more races. 7.60% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race (1.6% Puerto Rican, 1.4% Mexican, 0.6% Dominican, 0.5% Colombian & Salvadoran, 0.4% Spaniard). Non-Hispanic Whites were 62.1% of the population in 2010,[82] down from 89.7% in 1970.[83] An individual resident of Cambridge is known as a Cantabrigian.

In 2010, there were 44,032 households, out of which 16.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 28.9% were married couples living together, 8.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 60.4% were non-families. 40.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.00 and the average family size was 2.76.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 13.3% of the population under the age of 18, 21.2% from 18 to 24, 38.6% from 25 to 44, 17.8% from 45 to 64, and 9.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 30.5 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $47,979, and the median income for a family was $59,423 (these figures had risen to $58,457 and $79,533 respectively as of a 2007 estimate[update][90]). Males had a median income of $43,825 versus $38,489 for females. The per capita income for the city was $31,156. About 8.7% of families and 12.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 15.1% of those under age 18 and 12.9% of those age 65 or over.

Cambridge has been ranked as one of the most liberal cities in America.[91] Locals living in and near the city jokingly refer to it as "The People's Republic of Cambridge".[92] For 2016, the residential property tax rate in Cambridge was $6.99 per $1,000.[93] Cambridge enjoys the highest possible bond credit rating, AAA, with all three Wall Street rating agencies.[94]

In 2000, 11.0% of city residents were of Irish ancestry; 7.2% were of English, 6.9% Italian, 5.5% West Indian and 5.3% German ancestry. 69.4% spoke only English at home, while 6.9% spoke Spanish, 3.2% Chinese or Mandarin, 3.0% Portuguese, 2.9% French Creole, 2.3% French, 1.5% Korean, and 1.0% Italian.

Income

Data is from the 2009–2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.[95]

| Rank | ZIP Code (ZCTA) | Per capita income |

Median household income |

Median family income |

Population | Number of households |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 02142 | $67,525 | $100,114 | $150,774 | 2,838 | 1,385 |

| 2 | 02138 | $52,592 | $75,446 | $120,564 | 35,554 | 13,868 |

| 3 | 02140 | $50,856 | $75,446 | $120,564 | 18,164 | 8,460 |

| Cambridge | $47,448 | $72,529 | $93,460 | 105,737 | 44,345 | |

| Middlesex County | $42,861 | $82,090 | $104,032 | 1,522,533 | 581,120 | |

| 4 | 02139 | $42,235 | $71,745 | $93,220 | 36,015 | 14,474 |

| 5 | 02141 | $39,241 | $64,326 | $76,276 | 13,126 | 6,182 |

| Massachusetts | $35,763 | $66,866 | $84,900 | 6,605,058 | 2,530,147 | |

| United States | $28,155 | $53,046 | $64,719 | 311,536,594 | 115,610,216 |

Economy

Manufacturing was an important part of Cambridge's economy in the late 19th and early 20th century, but educational institutions are its biggest employers today. Harvard and MIT together employ about 20,000.[96][97] As a cradle of technological innovation, Cambridge was home to technology firms Analog Devices, Akamai, Bolt, Beranek, and Newman (BBN Technologies) (now part of Raytheon), General Radio (later GenRad), Lotus Development Corporation (now part of IBM), Polaroid, Symbolics, and Thinking Machines.

In 1996, Polaroid, Arthur D. Little, and Lotus were Cambridge's top employers, with over 1,000 employees, but they faded out a few years later. Health care and biotechnology firms such as Genzyme, Biogen Idec, bluebird bio, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, Pfizer and Novartis[98] have significant presences in the city. Though headquartered in Switzerland, Novartis continues to expand its operations in Cambridge.

Other major biotech and pharmaceutical firms expanding their presence in Cambridge include GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Shire, and Pfizer.[99] Most of Cambridge's biotech firms are in Kendall Square and East Cambridge, which decades ago were the city's center of manufacturing. Some others are in University Park at MIT, a new development in another former manufacturing area.[100][101]

None of the high technology firms that once dominated the economy was among the 25 largest employers in 2005, but by 2008 Akamai and ITA Software were.[96] Google,[102] IBM Research, Microsoft Research, and Philips Research[103] maintain offices in Cambridge. In late January 2012—less than a year after acquiring Billerica-based analytic database management company, Vertica—Hewlett-Packard announced it would also be opening its first offices in Cambridge.[104] Also around that time, e-commerce giants Staples[105] and Amazon.com[106] said they would be opening research and innovation centers in Kendall Square. And LabCentral provides a shared laboratory facility for approximately 25 emerging biotech companies.[107][108][unreliable source?]

The proximity of Cambridge's universities has also made the city a center for nonprofit groups and think tanks, including the National Bureau of Economic Research, the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cultural Survival, and Science Club for Girls.[citation needed]

In September 2011, Cambridge launched its Entrepreneur Walk of Fame initiative, recognizing people who have made contributions to innovation in global business.[109]

In 2021, Cambridge was one of approximately 27 US cities to receive a AAA rating from each of the three major US credit rating agencies, Moody's Investors Service, Standard & Poor's and Fitch Ratings. 2021 marked the 22nd consecutive year that Cambridge had retained this distinction.[110]

Top employers

As of 2019[update], the city's ten largest employers are:[97]

| # | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Harvard University | 12,565 |

| 2 | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | 9,311 |

| 3 | City of Cambridge | 3,256 |

| 4 | Takeda Pharmaceuticals | 3,484 |

| 5 | Biogen | 2,421 |

| 6 | Novartis Inst. For Biomedical Research | 2,267 |

| 6 | Cambridge Innovation Center | 2,267 |

| 8 | Cambridge Health Alliance | 1,806 |

| 9 | Mt. Auburn Hospital | 1,789 |

| 10 | Sanofi Genzyme | 1,782 |

Arts and culture

Museums

- Harvard Art Museum, including the Busch-Reisinger Museum, a collection of Germanic art, the Fogg Art Museum, a comprehensive collection of Western art, and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, a collection of Middle East and Asian art

- Harvard Museum of Natural History, including the Glass Flowers collection

- List Visual Arts Center, MIT

- MIT Museum

- Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard

- Semitic Museum, Harvard

Public art

Cambridge has a large and varied collection of permanent public art, on both city property, managed by the Cambridge Arts Council,[111] Community Art Center,[112] and the Harvard[113] and MIT[114] campuses. Temporary public artworks are displayed as part of the annual Cambridge River Festival on the banks of the Charles River during winter celebrations in Harvard and Central Squares and at Harvard University campus sites. Experimental forms of public artistic and cultural expression include the Central Square World's Fair, the annual Somerville-based Honk! Festival,[115] and If This House Could Talk,[116] a neighborhood art and history event.

Street musicians and other performers entertain tourists and locals in Harvard Square during the warmer months. The performances are coordinated through a public process that has been developed collaboratively by the performers,[117] city administrators, private organizations and business groups.[118] The Cambridge public library contains four Works Progress Administration murals completed in 1935 by Elizabeth Tracy Montminy: Religion, Fine Arts, History of Books and Paper, and The Development of the Printing Press.[119]

Architecture

Despite intensive urbanization during the late 19th century and the 20th century, Cambridge has several historic buildings, including some from the 17th century. The city also has abundant contemporary architecture, largely built by Harvard and MIT.

Notable historic buildings in the city include:

- The Asa Gray House (1810)

- Austin Hall, Harvard University (1882–1884)

- Cambridge City Hall (1888–1889)

- Cambridge Public Library (1888)

- Christ Church, Cambridge (1761)

- Cooper-Frost-Austin House (1689–1817)

- Elmwood House (1767), residence of the president of Harvard University

- First Church of Christ, Scientist (1924–1930)

- The First Parish in Cambridge (1833)

- Harvard-Epworth United Methodist Church (1891–1893)

- Harvard Lampoon Building (1909)

- The Hooper-Lee-Nichols House (1685–1850)

- Longfellow House–Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site (1759), former home of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and headquarters of George Washington

- The Memorial Church of Harvard University (1932)

- Memorial Hall, Harvard University (1870–1877)

- Middlesex County Courthouse (1814–1848)

- Urban Rowhouse (1875)

- O'Reilly Spite House (1908), built to spite a neighbor who would not sell his adjacent land[120]

Contemporary architecture:

- Arthur M. Sackler Museum at Harvard University, one of the few buildings in the U.S. by Pritzker Prize winner James Stirling

- Baker House dormitory at MIT by Finnish architect Alvar Aalto, one of only two Aalto buildings in the U.S.

- Harvard Graduate Center/Harkness Commons by The Architects Collaborative with Walter Gropius

- Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard, the only Le Corbusier building in North America

- Design Research Building by Benjamin Thompson and Associates

- Harvard Science Center, Holyoke Center, and Peabody Terrace by Catalan architect and Harvard Graduate School of Design Dean Josep Lluís Sert

- Kresge Auditorium, MIT, by Eero Saarinen

- Harvard Art Museums, renovation and major expansion of Fogg Museum building, completed in 2014 by Renzo Piano

- MIT Chapel by Eero Saarinen

- MIT Media Lab, two buildings by I. M. Pei and Fumihiko Maki

- Simmons Hall at MIT by Steven Holl

- Stata Center, home to the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, the Department of Linguistics, and the Department of Philosophy by Frank Gehry

Music

The city has an active music scene, from classical performances to the latest popular bands. Beyond its colleges and universities, Cambridge has many music venues, including The Middle East, Club Passim, The Plough and Stars, The Lizard Lounge and the Nameless Coffeehouse.

Parks and recreation

Consisting largely of densely built residential space, Cambridge lacks significant tracts of public parkland. Easily accessible open space on the university campuses, including Harvard Yard, Radcliffe Yard, and MIT's Great Lawn, as well as the considerable open space of Mount Auburn Cemetery and Fresh Pond Reservation, partly compensates for this. At Cambridge's western edge, the cemetery is known as a garden cemetery because of its landscaping (the oldest planned landscape in the country) and arboretum. Although known as a Cambridge landmark, much of the cemetery lies within Watertown.[121] It is also an Important Bird Area (IBA) in the Greater Boston area. Fresh Pond Reservation is the largest open green space in Cambridge with 162 acres (656,000 m2) of land around a 155-acre (627,000 m2) kettle hole lake. This land includes a 2.25-mile walking trail around the reservoir and a public nine-hole golf course.[122]

Public parkland includes the esplanade along the Charles River, which mirrors its Boston counterpart, Cambridge Common, Danehy Park, and Alewife Brook Reservation.

Government

Federal and state representation

| Voter registration and party enrollment as of February 24, 2024[update][123] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 36,319 | 48.67% | |||

| Republican | 1,616 | 2.17% | |||

| Unaffiliated | 36,183 | 48.49% | |||

| Libertarian | 131 | 0.18% | |||

| Total | 74,616 | 100% | |||

Cambridge is split between Massachusetts's 5th and 7th U.S. congressional districts. The 5th district seat is held by Democrat Katherine Clark, who replaced now-Senator Ed Markey in a 2013 special election; the 7th is represented by Democrat Ayanna Pressley, elected in 2018. The state's senior United States senator is Democrat Elizabeth Warren, elected in 2012, who lives in Cambridge. The governor of Massachusetts is Democrat Maura Healey, elected in 2022.

Cambridge is represented in six districts in the Massachusetts House of Representatives: the 24th Middlesex (which includes parts of Belmont and Arlington), the 25th and 26th Middlesex (the latter of which includes a portion of Somerville), the 29th Middlesex (which includes a small part of Watertown), and the Eighth and Ninth Suffolk (both including parts of the City of Boston).[124] The city is represented in the Massachusetts Senate as a part of the 2nd Middlesex, Middlesex and Suffolk, and 1st Suffolk and Middlesex districts.[125]

Politics

From 1860 to 1880, Republicans Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, and James Garfield each won Cambridge, Grant doing so by margins of over 20 points in both of his campaigns. Following that, from 1884 to 1892, Grover Cleveland won Cambridge in all three of his presidential campaigns, by less than ten points each time.

Then from 1896 to 1924, Cambridge became something of a swing city with a slight Republican lean. Republican candidates carried the city in five of the eight presidential elections during that time, with five of the elections resulting in either a plurality or a margin of victory of fewer than ten points.

In modern times, however, Cambridge has been a stronghold of the Democratic Party. In the last 23 presidential elections, dating back to the nomination of Al Smith in the 1928 presidential election, Democratic presidential candidates have won Cambridge with every Democratic nominee since Massachusetts native John F. Kennedy in 1960 receiving at least 70% of the vote, except for Jimmy Carter in 1976 and 1980. Since 1928, the only Republican nominee to come within ten points of carrying Cambridge is Dwight Eisenhower in his 1956 reelection bid.

| Year | Democratic | Republican |

|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 87.2% 43,690 | 8.3% 4,159 |

| 2020 | 91.7% 50,233 | 6.4% 3,519 |

| 2016 | 87.9% 46,563 | 6.3% 3,323 |

| 2012 | 86.0% 43,515 | 10.8% 5,476 |

| 2008 | 87.8% 40,876 | 10.1% 4,697 |

| 2004 | 84.8% 35,886 | 12.6% 5,338 |

| 2000 | 72.1% 28,846 | 12.9% 5,166 |

| 1996 | 78.9% 30,043 | 13.1% 4,990 |

| 1992 | 74.7% 30,737 | 14.2% 5,847 |

| 1988 | 77.0% 32,027 | 21.1% 8,770 |

| 1984 | 76.2% 32,582 | 23.4% 10,007 |

| 1980 | 60.8% 24,337 | 19.9% 7,952 |

| 1976[127] | 68.7% 29,052 | 24.6% 10,424 |

| 1972[128] | 74.0% 30,486 | 25.4% 10,464 |

| 1968[129] | 76.8% 29,386 | 17.9% 6,840 |

| 1964[130] | 83.6% 36,009 | 13.4% 5,764 |

| 1960[131] | 70.3% 34,029 | 28.3% 13,691 |

| 1956[132] | 49.7% 25,240 | 48.3% 24,538 |

| 1952[133] | 56.2% 31,668 | 41.8% 23,526 |

| 1948[134] | 62.6% 33,501 | 32.1% 17,149 |

| 1944[135] | 58.4% 27,629 | 36.2% 17,149 |

| 1940[136] | 58.8% 30,412 | 38.6% 19,967 |

| 1936[137] | 55.9% 25,917 | 33.4% 15,495 |

| 1932[138] | 60.9% 24,585 | 35.0% 14,121 |

| 1928[139] | 60.9% 25,794 | 37.0% 15,662 |

| 1924[140] | 37.2% 11,321 | 49.5% 15,048 |

| 1920[141] | 38.6% 10,808 | 58.2% 16,289 |

| 1916[142] | 55.6% 7,999 | 42.8% 6,149 |

| 1912[143] | 48.7% 6,665 | 24.5% 3,360 |

| 1908[144] | 43.5% 5,562 | 51.6% 6,595 |

| 1904[145] | 48.7% 6,769 | 48.3% 6,706 |

| 1900[146] | 46.2% 5,249 | 50.3% 5,717 |

| 1896[147] | 25.6% 2,868 | 64.8% 7,247 |

| 1892[148] | 53.6% 5,996 | 44.2% 4,945 |

| 1888[149] | 51.4% 4,832 | 46.1% 4,330 |

| 1884[150] | 47.8% 4,040 | 40.6% 3,430 |

| 1880[151] | 43.5% 3,293 | 55.9% 4,227 |

| 1876[152] | 49.1% 3,531 | 50.9% 3,654 |

| 1872[153] | 34.8% 1,753 | 65.2% 3,289 |

| 1868[154] | 39.2% 1,982 | 60.8% 3,079 |

| 1864[155] | 38.0% 1,693 | 62.0% 2,760 |

| 1860[156] | 24.6% 888 | 50.0% 1,805 |

City government

Cambridge has a city government led by a mayor and a nine-member city council. There is also a six-member school committee that functions alongside the superintendent of public schools. The councilors and school committee members are elected every two years using proportional representation.[157]

The mayor is elected by the city councilors from among themselves and serves as the chair of city council meetings. The mayor also sits on the school committee. The mayor is not the city's chief executive. Rather, the city manager, who is appointed by the city council, serves in that capacity.

Under the city's Plan E form of government, the city council does not have the power to appoint or remove city officials who are under the direction of the city manager. The city council and its members are also forbidden from giving orders to any subordinate of the city manager.[158]

Yi-An Huang is the City Manager as of September 6, 2022, succeeding Owen O'Riordan (now the Deputy City Manager) who briefly served as the Acting City Manager after Louis DePasquale resigned on July 5, 2022, after six years in office.[159]

| District | Councillor | In office since |

|---|---|---|

| At-large | Burhan Azeem | Jan. 2022 |

| At-large | Marc C. McGovern** | Jan. 2014 |

| At-large | Patty Nolan | Jan. 2020 |

| At-large | Joan Pickett | Jan. 2024 |

| At-large | Sumbul Siddiqui** | Jan. 2018 |

| At-large | E. Denise Simmons* | Jan. 2002 |

| At-large | Jivan Sobrinho-Wheeler | Jan. 2024 |

| At-large | Paul Toner | Jan. 2022 |

| At-large | Ayesha Wilson | Jan. 2024 |

* = current mayor

** = former mayor

On March 8, 2021, Cambridge City Council voted to recognize polyamorous domestic partnerships, becoming the second city in the United States following neighboring Somerville, which had done so in 2020.[160]

County government

Cambridge was a county seat of Middlesex County, along with Lowell, until the abolition of executive county government. Though the county government was abolished in 1997, the county still exists as a geographical and political region. The employees of Middlesex County courts, jails, registries, and other county agencies now work directly for the state. The county's registrars of Deeds and Probate remain in Cambridge, but the Superior Court and District Attorney have had their operations transferred to Woburn. Third District Court has shifted operations to Medford, and the county Sheriff's office awaits near-term relocation.[161]

Education

Higher education

Cambridge is perhaps best known as an academic and intellectual center. Its colleges and universities include:

- Cambridge School of Culinary Arts

- Harvard University

- Hult International Business School

- Lesley University

- Longy School of Music of Bard College

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology

At least 258 of the world's total 962 Nobel Prize winners have at some point in their careers been affiliated with universities in Cambridge.

Cambridge College is named for Cambridge and was based in Cambridge until 2017, when it consolidated to a new headquarters in neighboring Boston.

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences, one of the nation's oldest learned societies founded in 1780, is based in Cambridge.

Primary and secondary public education

The city's schools constitute the Cambridge Public School District. Schools include:

- Amigos School

- Baldwin School (formerly the Agassiz School)

- Cambridgeport School

- Fletcher-Maynard Academy

- Graham and Parks Alternative School

- Haggerty School

- Kennedy-Longfellow School

- King Open School

- Martin Luther King Jr. School

- Morse School (a Core Knowledge school)

- Peabody School

- Tobin School (a Montessori school)

Five upper schools offer grades 6–8 in some of the same buildings as the elementary schools:[162]

- Amigos School

- Cambridge Street Upper School

- Putnam Avenue Upper School

- Rindge Avenue Upper School

- Vassal Lane Upper School

Cambridge has three district public high school programs, including Cambridge Rindge and Latin School (CRLS).[163]

Other public charter schools include Benjamin Banneker Charter School, which serves grades K–6;[164] Community Charter School of Cambridge[165] in Kendall Square, which serves grades 7–12; and Prospect Hill Academy, a charter school whose upper school is in Central Square though it is not a part of the Cambridge Public School District.

Primary and secondary private education

Cambridge also has several private schools, including:

- Boston Archdiocesan Choir School

- Buckingham Browne & Nichols School

- Cambridge Montessori school

- Cambridge Friends School

- Fayerweather Street School[166]

- International School of Boston (formerly École Bilingue)

- Matignon High School

- Shady Hill School

- St. Peter School

Media

As part of the Metro Boston area, the city's primary network-affiliated television stations are WBTS-CD (NBC), WBZ-TV (CBS), WCVB-TV (ABC), and WFXT (Fox). There are several additional local stations that are accessible over the air without the need of cable, etc. access. The city also is served by WGBH-TV and WGBX-TV, which are PBS member stations, with WGBH being the flagship station of the statewide WGBH Educational Foundation network. Several TV services provide different portions of Cambridge with cable, DSL, fiber and satellite TV broadcasts and Internet including AT&T U-verse/DIRECTV,[167] Comcast/Xfinity,[168] and DISH Network..

Newspapers

Cambridge is served by a single online newspaper, Cambridge Day. The last physical newspaper in the city, Cambridge Chronicle, ceased publication in 2022 and today only cross-posts regional stories from other Gannett properties.

Radio

Cambridge is home to the following radio stations, including both commercially licensed and student-run stations:

| Callsign | Frequency | City/town | Licensee | Format |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHRB | 95.3 FM | Cambridge (Harvard) | Harvard Radio Broadcasting Co., Inc. | Musical variety |

| WJIB | 740 AM/101.3 FM | Cambridge | Bob Bittner Broadcasting | Adult standards/Pop |

| WMBR | 88.1 FM | Cambridge (MIT) | Technology Broadcasting Corporation | College radio |

Television and broadband

Cambridge Community Television (CCTV) has served the city since its inception in 1988. CCTV operates Cambridge's public access television facility and three television channels, 8, 9, and 96, on the XFinity cable system (Comcast). The city has invited tenders from other cable providers, but Comcast remains its only fixed television and broadband utility,[169] though services from American satellite TV providers are available. In October 2014, Cambridge City Manager Richard Rossi appointed a citizen Broadband Task Force to "examine options to increase competition, reduce pricing, and improve speed, reliability and customer service for both residents and businesses."[170]

Infrastructure

Utilities

- Cable television service is provided by XFINITY (Comcast Communications).[171]

- Parts of Cambridge are served by a district heating systems loop for industrial organizations that also cover Boston.

- Electric service and natural gas are both provided by Eversource Energy.[171]

- Landline telecommunications service are provided by Harvard University,[172] Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT),[173] and Verizon Communications. All phones in Cambridge are inter-connected to central office locations in the metropolitan area.

- The city maintains its own Public, educational, and government access (PEG) known as Cambridge Community Television (CCTV).

Water department

Cambridge obtains water from Hobbs Brook (in Lincoln and Waltham) and Stony Brook (Waltham and Weston), as well as an emergency connection to the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority.[174] The city owns over 1,200 acres (486 ha) of land in other towns that includes these reservoirs and portions of their watershed.[175] Water from these reservoirs flows by gravity through an aqueduct to Fresh Pond in Cambridge. It is then treated in an adjacent plant and pumped uphill to an elevation of 176 feet (54 m) above sea level at the Payson Park Reservoir (Belmont). The water is then redistributed downhill via gravity to individual users in the city.[176] A new water treatment plant opened in 2001.[177]

In October 2016, the city announced that, owing to drought conditions, they would begin buying water from the MWRA.[178] On January 3, 2017, Cambridge announced that "As a result of continued rainfall each month since October 2016, we have been able to significantly reduce the need to use MWRA water. We have not purchased any MWRA water since December 12, 2016 and if 'average' rainfall continues this could continue for several months."[179]

- Sewer service is available in Cambridge. The city is inter-connected with the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA)'s sewage network with sewage treatment plant in the Boston Harbor.

Transportation

Road

Cambridge is served by several major roads, including Route 2, Route 16, and the Route 28. The Massachusetts Turnpike does not pass through Cambridge but is accessible by an exit in nearby Allston. Both U.S. Route 1 and Interstate 93 provide additional access at the eastern end of Cambridge via Leverett Circle in Boston. Route 2A runs the length of the city, chiefly along Massachusetts Avenue. The Charles River forms the southern border of Cambridge and is crossed by 11 bridges connecting Cambridge to Boston, eight of which are open to motorized road traffic, including the Longfellow Bridge and the Harvard Bridge.

Cambridge has an irregular street network because many of the roads date from the colonial era. Contrary to popular belief, the road system did not evolve from longstanding cow-paths. Roads connected various village settlements with each other and nearby towns and were shaped by geographic features, most notably streams, hills, and swampy areas.[180] Today, the major "squares" are typically connected by long, mostly straight roads, such as Massachusetts Avenue between Harvard Square and Central Square or Hampshire Street between Kendall Square and Inman Square.

On October 25, 2022, Cambridge City Council voted 8–1 to eliminate parking minimums from the city code, citing declining car ownership, with the aim of promoting housing construction.[181][182]

Mass transit

Cambridge is served by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, including Porter station on the regional Commuter Rail, Lechmere station on the Green Line, and Alewife, Porter, Harvard, Central, and Kendall Square/MIT stations on the Red Line. Alewife station, the terminus of the Red Line, has a large multi-story parking garage.[183]

The Harvard bus tunnel under Harvard Square connects to the Red Line underground. This tunnel was originally opened for streetcars in 1912 and served trackless trolleys, trolleybuses, and buses as the routes were converted; four lines of the MBTA trolleybus system continued to use it until their conversion to diesel in 2022.[184] The tunnel was partially reconfigured when the Red Line was extended to Alewife in the early 1980s.

Both Union Square station in Somerville on the Green Line and Community College station in Charlestown on the Orange Line are located just outside of Cambridge.

Besides the state-owned transit agency, the city is also served by the Charles River Transportation Management Agency (CRTMA) shuttles which are supported by some of the largest companies operating in the city, in addition to the municipal government itself.[185]

Cycling

Cambridge has several bike paths, including one along the Charles River,[186] and the Linear Park connecting the Minuteman Bikeway at Alewife with the Somerville Community Path. A connection to Watertown opened in 2022. Bike parking is common and there are bike lanes on many streets, although concerns have been expressed regarding the suitability of many of the lanes. On several central MIT streets, bike lanes transfer onto the sidewalk. Cambridge bans cycling on certain sections of sidewalk where pedestrian traffic is heavy.[187]

Bicycling Magazine in 2006 rated Boston as one of the worst cities in the nation for bicycling,[188] but it has given Cambridge honorable mention as one of the best[189] and was called "Boston's great hope" by the magazine. Boston has since then followed the example of Cambridge and made considerable efforts to improve bicycling safety and convenience.[190]

Walking

Walking is a popular activity in Cambridge. In 2000, among U.S. cities with more than 100,000 residents, Cambridge had the highest percentage of commuters who walked to work.[191] Cambridge's major historic squares have changed into modern walking neighborhoods, including traffic calming features based on the needs of pedestrians rather than of motorists.[192]

Intercity

The Boston intercity bus and train stations at South Station in Boston, and Logan International Airport in East Boston, both of which are accessible by subway. The Fitchburg Line rail service from Porter Square connects to some western suburbs. Since October 2010, there has also been intercity bus service between Alewife Station (Cambridge) and New York City.[193]

Police department

In addition to the Cambridge Police Department, the city is patrolled by the Fifth (Brighton) Barracks of Troop H of the Massachusetts State Police.[194] Owing, however, to proximity, the city also practices functional cooperation with the Fourth (Boston) Barracks of Troop H, as well.[195] The campuses of Harvard and MIT are patrolled by the Harvard University Police Department and MIT Police Department, respectively.

Fire department

The city of Cambridge is protected by the Cambridge Fire Department. Established in 1832, the CFD operates eight engine companies, four ladder companies, one rescue company, and three paramedic squad companies from eight fire stations located throughout the city. The Acting Chief is Thomas F. Cahill Jr.[196]

Emergency medical services (EMS)

The city of Cambridge receives emergency medical services from PRO EMS, a privately contracted ambulance service.[197]

Public library services

Further educational services are provided at the Cambridge Public Library. The large modern main building was built in 2009, and connects to the restored 1888 Richardson Romanesque building. It was founded as the private Cambridge Athenaeum in 1849 and was acquired by the city in 1858, and became the Dana Library. The 1888 building was a donation of Frederick H. Rindge.

Sister cities and twin towns

Cambridge's sister cities with active relationships are:[198]

Cambridge has ten additional inactive sister city relationships:[198]

Dublin, Ireland (1983)

Dublin, Ireland (1983) Ischia, Italy (1984)

Ischia, Italy (1984) Catania, Italy (1987)

Catania, Italy (1987) Kraków, Poland (1989)

Kraków, Poland (1989) Florence, Italy (1992)

Florence, Italy (1992) Santo Domingo Oeste, Dominican Republic (2003)

Santo Domingo Oeste, Dominican Republic (2003) Southwark, England (2004)

Southwark, England (2004) Yuseong (Daejeon), Korea (2005)

Yuseong (Daejeon), Korea (2005) Haidian (Beijing), China (2005)

Haidian (Beijing), China (2005) Cienfuegos, Cuba (2005)

Cienfuegos, Cuba (2005)

Notes

References

Citations

- ^ Cambridge Historical Commission. "Frequently Asked Questions". City of Cambridge. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ^ Levy, Marc (January 1, 2024). "Simmons and McGovern return as mayoral team after Cambridge inaugural is disrupted by protest". Cambridge Day.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ "Cambridge". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States". USDOC. Population, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- ^ Degler, Carl Neumann (1984). Out of Our Pasts: The Forces That Shaped Modern America. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-131985-3. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- ^ "World Reputation Rankings". Times Higher Education. April 21, 2016. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2016.[title missing]

- ^ a b "Kendall Square Initiative". MIT. Archived from the original on January 17, 2017. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ "July 3, 1775: George Washington takes command of Continental Army" Archived February 20, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, History.com

- ^ "Cambridge", George Washington's Mount Vernon website

- ^ "You live in Anmoughcawgen". History Cambridge. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ Smith, John (1837). A description of New England; or, The observations, and discoveries of Captain Iohn Smith (admirall of that country) in the north of America, in the year of our Lord 1614; with the successe of sixe ships, that went the next yeare 1615; and the accidents befell him among the French men of warre: with the proofe of the present benefit this countrey affoords; whither this present yeare, 1616, eight voluntary ships are gone to make further tryall. Washington: P. Force. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h EB (1878).

- ^ a b Abbott, Rev. Edward (1880). "Cambridge". In Drake, Samuel Adams (ed.). History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts. Vol. 1. Boston: Estes and Lauriat. pp. 305–16. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ^ Report on the Custody and Condition of the Public Records of Parishes. Boston: Massachusetts Secretary of the Commonwealth. 1889. p. 298. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved December 24, 2008.

- ^ (1) Arthur Gilman, ed. (1896). The Cambridge of Eighteen Hundred and Ninety-six. Cambridge: Committee on the Memorial Volume. p. 8.

(2) Harvard News Office (May 2, 2002). "This month in Harvard history". Harvard Gazette. Archived from the original on January 18, 2012. Retrieved April 28, 2012.. (This source gives May 12, 1638, as the date of the name change; others say May 2, 1638, or late 1637.) - ^ Historic Guide to Cambridge (Second ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Hannah Winthrop Chapter, D.A.R. 1907. pp. 20–21.

On October 15, 1637, the Great and General Court passed a vote that: "The college is ordered to bee at Newetowne." In this same year the name of Newetowne was changed to Cambridge, ("It is ordered that Newetowne shall henceforward be called Cambridge") in honor of the university in Cambridge, England, where many of the early settlers were educated.

- ^ "Brief History of Cambridge, Massachusetts". Town of Cambridge. 2021. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015.

- ^ "Medford Historical Society Papers, Volume 24., The Indians of the Mystic valley and the litigation over their land". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on December 10, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ Ritter, Priscilla R.; Thelma Fleishman (1982). Newton, Massachusetts 1679–1779: A Biographical Directory. New England Historic Genealogical Society.

- ^ "History", Lexington Chamber of Commerce, 2007, archived from the original on March 10, 2007

- ^ William P., Marchione (2011). "A Short History of Allston-Brighton". Brighton-Allston Historical Society. Brighton Board of Trade. Archived from the original on February 20, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ (1) "Annexation And Its Fruits". The New York Times. January 15, 1874. p. 4. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

(2) "Boston's Annexation Schemes.; Proposal To Absorb Cambridge And Other Near-By Towns". The New York Times. March 26, 1892. p. 11. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved August 21, 2010. - ^ "Descendants of the Great Migration". The Winthrop Society. Archived from the original on June 22, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ (1) "Harvard Charter of 1650". Harvard University Archives. Archived from the original on July 2, 2013. Retrieved September 7, 2013.

(2) "Chapter V: The University at Cambridge, and encouragement of literature, etc.". Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The General Court of Massachusetts. September 1, 1779. Archived from the original on July 7, 2010. Retrieved December 13, 2009. - ^ EB (1911), p. 96.

- ^ "Kennedy, F. A., Steam Bakery – Cambridge, Massachusetts – U.S. National Register of Historic Places". waymarking.com. Archived from the original on July 30, 2018. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ "Candy Land: The History of Candy Making in Cambridge, Massachusetts – Squirrel Brand Nuts". cambridgehistory.org. Archived from the original on April 30, 2014.

- ^ "Candy Land: The History of Candy Making in Cambridge, Massachusetts – George Close Company". cambridgehistory.org. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ "Candy Land: The History of Candy Making in Cambridge, Massachusetts – Daggett Chocolate". cambridgehistory.org. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ "Candy Land: The History of Candy Making in Cambridge, Massachusetts – Fox Cross Co". cambridgehistory.org. Archived from the original on October 27, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ a b "Candy Land: The History of Candy Making in Cambridge, Massachusetts – James O. Welch". cambridgehistory.org. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ "Unwrapping the lost history of Confectioner's Row". November 22, 2022. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ Rothstein, Richard (2017). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation. p. 26. ISBN 978-1631494536.

- ^ "Cambridge Housing Authority - Newtowne Court". Cambridge Housing Authority. Archived from the original on July 23, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ "Cambridge Housing Authority – Washington Elms". Cambridge Housing Authority. Archived from the original on July 23, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Featherly, Kevin (July 15, 2024). "ARPANET: United States defense program". Britannica. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ "Locations – Akamai". Akamai.com. Archived from the original on May 20, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ "How Cambridge became the life sciences capital". www.betaboston.com. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f "Renters who needed to move couldn't qualify". Mass Landlords, Inc. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ a b Havemann, Judith (September 19, 1998). "Mass. City Gets New Lease on Life". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Towns lost tax revenue". Mass Landlords, Inc. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ Autor, David H.; Palmer, Christopher J.; Pathak, Parag A. (June 2014). "Housing Market Spillovers: Evidence from the End of Rent Control in Cambridge, Massachusetts". Journal of Political Economy. 122 (3): 661–717. doi:10.1086/675536. hdl:1721.1/104081. JSTOR 10.1086/675536.

- ^ Glaeser, E. L. (April 1, 2005). "Reinventing Boston: 1630–2003". Journal of Economic Geography. 5 (2): 119–153. doi:10.1093/jnlecg/lbh058. ISSN 1468-2702.

- ^ McLean, Danielle. "Housing prices soar after years of stability in Cambridge". Cambridge Chronicle & Tab. Archived from the original on March 3, 2017. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ (1) "City Council Policy Order Resolution O-16". City of Cambridge. May 8, 2006. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

(2) Mason, Melanie; Mishak, Michael J.; Powers, Ashley (April 21, 2013). "In immigrant-rich Cambridge, arrest baffles locals". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2013. - ^ (1) No Writer Attributed (September 18, 1969). ""Cambridge: A City of Squares" Harvard Crimson, September 18, 1969". Thecrimson.com. Archived from the original on March 10, 2012. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

(2) "Cambridge Journal: Massachusetts City No Longer in Boston's Shadow". Travelwritersmagazine.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved April 28, 2012. - ^ Lelund Cheung. "When a neighborhood is crowned the most innovative square mile in the world, how do you keep it that way?". Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC. Archived from the original on December 2, 2016. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Murthy, Rekha (October 2004). "Central Square, Cambridge: Rising Fortunes at a Regional Crossroads" (PDF). rmurthy.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2006.

- ^ "Getting to Know Your Neighborhood: Central Square". Boston University. April 6, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Cambridgeport - Neighborhood 5 - CDD - City of Cambridge, Massachusetts". www.cambridgema.gov. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Harvard Square Things To Do and Information Guide". Old Town Trolley Tours. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ Crocket, Douglas S.; Hirshson, Paul (March 3, 1985). "T dedicates new Harvard station". The Boston Globe. p. 43. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ "Cambridge Transportation". Harvard Square. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ "The areas, neighborhoods and squares of Cambridge". Cambridge Day. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ "Cambridge Neighborhood Planning - CDD - City of Cambridge, Massachusetts". www.cambridgema.gov. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ "Baldwin - Neighborhood 8 - CDD - City of Cambridge, Massachusetts". www.cambridgema.gov. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ "Porter Square/North Massachusetts Avenue - CDD - City of Cambridge, Massachusetts". www.cambridgema.gov. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Citation Needed", Retcon Game, University Press of Mississippi, April 3, 2017, doi:10.14325/mississippi/9781496811325.003.0047, ISBN 978-1-4968-1132-5, retrieved October 10, 2023

- ^ "Porter | Stations | MBTA". www.mbta.com. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Getting to Know Your Neighborhood: Inman Square". Boston University. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ "Lechmere | Stations | MBTA". www.mbta.com. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ Handy, Natalie. "Area Four in Cambridge renamed 'The Port'". Wicked Local. Archived from the original on March 21, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ "Climate Cambridge: Temperature, Climograph, Climate table for Cambridge – Climate-Data.org". en.climate-data.org. Archived from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- ^ "PRISM Climate Group at Oregon State University". Northwest Alliance for Computational Science & Engineering (NACSE), based at Oregon State University. Archived from the original on August 25, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020: CAMBRIDGE 0.9 NNW, MA". National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- ^ "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21–7 through 21–09, Massachusetts Table 4. Population of Urban Places of 10,000 or more from Earliest Census to 1920. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ United States Census Bureau (1909). A Century of Population Growth. p. 158.

- ^ "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2022". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States". Census.gov. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Cambridge city, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ a b "Cambridge (city), Massachusetts". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 27, 2014. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Massachusetts – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved May 4, 2012.

- ^ a b From 15% sample