Canadian pound

1 penny (2 sous) bank token (1837) | |

| Unit | |

|---|---|

| Plural | pounds |

| Symbol | £ |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 1⁄20 | shilling |

| 1⁄240 | penny |

| 1⁄480 | sou |

| Plural | |

| shilling | shillings |

| penny | pence |

| sou | sous |

| Symbol | |

| shilling | s or /– |

| penny | d |

| Demographics | |

| Date of introduction | 1841 |

| Date of withdrawal | 1858 |

| Replaced by | Canadian dollar |

| User(s) | Province of Canada |

| Valuation | |

| Value | £1 = $4 |

| This infobox shows the latest status before this currency was rendered obsolete. | |

The pound (symbol £) was the currency of the Canadas until 1858. It was subdivided into 20 shillings (s), each of 12 pence (d). In Lower Canada, the sou was used, equivalent to a halfpenny. Although the £sd accounting system had its origins in sterling, the Canadian pound was never at par with sterling's pound.

History

In North America, the scarcity of British coins led to the widespread use of Spanish dollars. These Spanish dollars were accommodated into a £sd account system, by setting a valuation for these coins in terms of a pound unit. At one stage, two such units were in widespread use in the British North American colonies. The Halifax rating dominated, and it set the Spanish dollar equal to 5/–. As this was 6d more than its value in silver, the Halifax pound was consequently lower in value than the sterling pound. The York rating of one Spanish dollar being to eight shillings was officially used in Upper Canada until it was outlawed in 1796, but continued to be used unofficially well into the early 19th century.

In 1825, an Imperial Order-in-Council was made for the purposes of causing sterling coinage to circulate in the British colonies. The idea was that this order-in-council would make the sterling coins legal tender at the exchange rate of 4s.4d. per Spanish dollar. This rate was in fact unrealistic and it had the adverse effect of actually driving out what little sterling-specie coinage was already circulating. Remedial legislation was introduced in 1838 but it was not applied to the British North American colonies due to recent uprisings in Upper and Lower Canada.

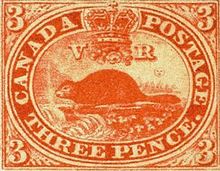

In 1841, the Province of Canada adopted a new system based on the Halifax rating. The new currency was equal to 4 U.S. dollars (92.88 grains gold), making one pound sterling equal to £1 4s 4d Canadian. Conversely the new Canadian pound was worth approximately 16s 5+1⁄4d sterling. The earliest Canadian postage stamps were denominated in this Halifax unit.

The 1850s was a decade of wrangling over whether to adopt an £sd monetary system or a decimal monetary system based on the US dollar. Local traders, for reasons of practicality in relation to the increasing trade with the neighbouring United States, had an overwhelming desire to assimilate the Canadian currency with the American unit, but the imperial authorities in London still preferred the idea of sterling to be the sole currency throughout the British Empire. In 1851, the Canadian parliament passed an act for the purposes of introducing an £sd unit in conjunction with decimal fractional coinage. The idea was that the decimal coins would correspond to exact amounts in relation to the US dollar fractional coinage. The authorities in London refused to give consent to the act on technical grounds, hoping that an £sd currency would be chosen instead. A currency with three new decimal units was proposed as a compromise to the Canadian legislature: 10 "minims" would be worth 1 "mark", 10 "marks" worth 1 shilling, and 10 shillings worth 1 "royal". A "mark" thus would have been worth 11⁄5d, and a "royal" would have been worth 2 crowns or half a pound.

This contrived mix of decimal and Sterling currency was abandoned and an 1853 act of the Legislative Assembly introduced the gold standard into Canada, with pounds, shilling, pence, dollars and cents all legal for keeping government accounts. This gold standard re-affirmed the value of British gold sovereigns set in 1841 at £1.4s.4d in local currency, and the American gold eagle at $10 in local dollars. In effect this created a Canadian dollar at par with the United States dollar, and Canadian pound at US$4.86+2⁄3. No coinage was provided for under the 1853 act but gold eagles and sterling gold and silver coinage were made legal tender. All other silver coins were demonetized.

In 1857 the Currency Act was amended, abolishing accounts in pounds and the use of sterling coinage as legal tender. Instead decimal 1¢, 5¢, 10¢, and 20¢ coins were introduced in 1858 at par with the US dollar, and postage stamps were issued with decimal denominations for the first time in 1859. British gold sovereigns and other gold coins continued to be legal tender.

New Brunswick followed Canada in adopting a decimal system pegged to the US dollar in November 1860. Nova Scotia also decimalized and adopted a dollar in 1860, but the Nova Scotians set their dollar's value to $5 per gold sovereign rather than $4.86+2⁄3.

Newfoundland introduced the gold standard in conjunction with decimal coinage in 1865, but unlike in the Provinces of Canada and New Brunswick they decided to adopt a unit based on the Spanish dollar rather than on the US dollar, at $4.80 per gold sovereign. This conveniently made the value of 2 Newfoundland cents equal to one penny, and in effect made the Newfoundland dollar valued at a slight premium ($1 = 4s.2d.) over the Canadian ($1 = 4s 1.3d) and Nova Scotian ($1 = 4/–) dollars. Newfoundland was the only part of the British Empire to introduce its own gold standard coin: a Newfoundland gold two dollar coin was minted intermittently until Newfoundland adopted the Canadian monetary system in 1895, following the Newfoundland banking crash.

In 1867 the Provinces of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia united in a federation called the Dominion of Canada and their three currencies were merged into the Canadian dollar.

In 1871 Prince Edward Island went decimal with a dollar pegged to the US and Canadian dollars, and introduced coins for 1 cent. However, the currency of Prince Edward Island was absorbed into the Canadian system shortly afterwards when Prince Edward island joined Canada in 1873.

Coins

Both Upper Canada (Canada West, modern southern Ontario) and Lower Canada (Canada East, modern southern Quebec) issued copper tokens. Between 1835 and 1852, the Bank of Montreal, La Banque du Peuple, the City Bank and the Quebec Bank issued 1- and 2-sou (1⁄2d and 1d) tokens for use in Lower Canada. The Bank of Upper Canada issued 1⁄2d and 1d tokens between 1850 and 1857.

Banknotes

On notes issued by the chartered banks, denominations were given in both dollars and pounds/shillings, with £1 = $4 and $1 = 5/– = 120 sous = 6 French livres. Many banks issued notes, starting with the Bank of Montreal in 1817. See Canadian chartered bank notes for more details. Denominations included 5/–, 10/–, 15/–, £1, £1+1⁄4, £2+1⁄2, £5, £12+1⁄2 and £25. In addition, small value, "scrip" notes were issued in 1837, by the Quebec Bank, in denominations of 6d (12 sous), $1⁄4 (30 sous, 1s.3d.) and $1⁄2 (60 sous, 2s.6d.), and by Arman's Bank, in denominations of 5d, 10d and 15d (10, 20 and 30 sous).

See also

- Bank of Canada

- Sterling area

- List of countries by leading trade partners

- Lists of Commonwealth of Nations countries by GDP

- List of countries by leading trade partners

- Canadian banknote issuers

References

- Krause, Chester L.; Clifford Mishler (1978). Standard Catalog of World Coins: 1979 Edition. Colin R. Bruce II (senior editor) (5th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873410203.

- Pick, Albert (1990). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: Specialized Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (6th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-149-8.