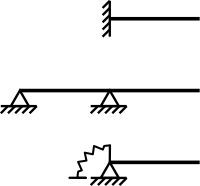

Cantilever

A cantilever is a rigid structural element that extends horizontally and is unsupported at one end. Typically it extends from a flat vertical surface such as a wall, to which it must be firmly attached. Like other structural elements, a cantilever can be formed as a beam, plate, truss, or slab.

When subjected to a structural load at its far, unsupported end, the cantilever carries the load to the support where it applies a shear stress and a bending moment.[1]

Cantilever construction allows overhanging structures without additional support.

In bridges, towers, and buildings

Cantilevers are widely found in construction, notably in cantilever bridges and balconies (see corbel). In cantilever bridges, the cantilevers are usually built as pairs, with each cantilever used to support one end of a central section. The Forth Bridge in Scotland is an example of a cantilever truss bridge. A cantilever in a traditionally timber framed building is called a jetty or forebay. In the southern United States, a historic barn type is the cantilever barn of log construction.

Temporary cantilevers are often used in construction. The partially constructed structure creates a cantilever, but the completed structure does not act as a cantilever. This is very helpful when temporary supports, or falsework, cannot be used to support the structure while it is being built (e.g., over a busy roadway or river, or in a deep valley). Therefore, some truss arch bridges (see Navajo Bridge) are built from each side as cantilevers until the spans reach each other and are then jacked apart to stress them in compression before finally joining. Nearly all cable-stayed bridges are built using cantilevers as this is one of their chief advantages. Many box girder bridges are built segmentally, or in short pieces. This type of construction lends itself well to balanced cantilever construction where the bridge is built in both directions from a single support.

These structures rely heavily on torque and rotational equilibrium for their stability.

In an architectural application, Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater used cantilevers to project large balconies. The East Stand at Elland Road Stadium in Leeds was, when completed, the largest cantilever stand in the world[2] holding 17,000 spectators. The roof built over the stands at Old Trafford uses a cantilever so that no supports will block views of the field. The old (now demolished) Miami Stadium had a similar roof over the spectator area. The largest cantilevered roof in Europe is located at St James' Park in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, the home stadium of Newcastle United F.C.[3][4]

Less obvious examples of cantilevers are free-standing (vertical) radio towers without guy-wires, and chimneys, which resist being blown over by the wind through cantilever action at their base.

-

The Forth Bridge, a cantilever truss bridge

-

This concrete bridge temporarily functions as a set of two balanced cantilevers during construction – with further cantilevers jutting out to support formwork.

-

Howrah Bridge in India, a cantilever bridge

-

A cantilevered balcony of the Fallingwater house, by Frank Lloyd Wright

-

A cantilevered railroad deck and fence on the Canton Viaduct

-

A cantilever barn in rural Tennessee

-

Cantilever barn at Cades Cove

-

A double jettied building in Cambridge, England

-

Cantilever occurring in the game "Jenga"

-

This radiograph of a "bridge" dental restoration features a cantilevered crown to the left.

-

Ronan Point: Structural failure of part of floors cantilevered from a central shaft.

-

Fiat Tagliero, a Futurist-style service station in Asmara, Eritrea, has a mirrored cantilevered roof.

Aircraft

The cantilever is commonly used in the wings of fixed-wing aircraft. Early aircraft had light structures which were braced with wires and struts. However, these introduced aerodynamic drag which limited performance. While it is heavier, the cantilever avoids this issue and allows the plane to fly faster.

Hugo Junkers pioneered the cantilever wing in 1915. Only a dozen years after the Wright Brothers' initial flights, Junkers endeavored to eliminate virtually all major external bracing members in order to decrease airframe drag in flight. The result of this endeavor was the Junkers J 1 pioneering all-metal monoplane of late 1915, designed from the start with all-metal cantilever wing panels. About a year after the initial success of the Junkers J 1, Reinhold Platz of Fokker also achieved success with a cantilever-winged sesquiplane built instead with wooden materials, the Fokker V.1.

In the cantilever wing, one or more strong beams, called spars, run along the span of the wing. The end fixed rigidly to the central fuselage is known as the root and the far end as the tip. In flight, the wings generate lift and the spars carry this load through to the fuselage.

To resist horizontal shear stress from either drag or engine thrust, the wing must also form a stiff cantilever in the horizontal plane. A single-spar design will usually be fitted with a second smaller drag-spar nearer the trailing edge, braced to the main spar via additional internal members or a stressed skin. The wing must also resist twisting forces, achieved by cross-bracing or otherwise stiffening the main structure.

Cantilever wings require much stronger and heavier spars than would otherwise be needed in a wire-braced design. However, as the speed of the aircraft increases, the drag of the bracing increases sharply, while the wing structure must be strengthened, typically by increasing the strength of the spars and the thickness of the skinning. At speeds of around 200 miles per hour (320 km/h) the drag of the bracing becomes excessive and the wing strong enough to be made a cantilever without excess weight penalty. Increases in engine power through the late 1920s and early 1930s raised speeds through this zone and by the late 1930s cantilever wings had almost wholly superseded braced ones.[5] Other changes such as enclosed cockpits, retractable undercarriage, landing flaps and stressed-skin construction furthered the design revolution, with the pivotal moment widely acknowledged to be the MacRobertson England-Australia air race of 1934, which was won by a de Havilland DH.88 Comet.[6]

Currently, cantilever wings are almost universal with bracing only being used for some slower aircraft where a lighter weight is prioritized over speed, such as in the ultralight class.

Cantilever in microelectromechanical systems

Cantilevered beams are the most ubiquitous structures in the field of microelectromechanical systems (MEMS). An early example of a MEMS cantilever is the Resonistor,[7][8] an electromechanical monolithic resonator. MEMS cantilevers are commonly fabricated from silicon (Si), silicon nitride (Si3N4), or polymers. The fabrication process typically involves undercutting the cantilever structure to release it, often with an anisotropic wet or dry etching technique. Without cantilever transducers, atomic force microscopy would not be possible. A large number of research groups are attempting to develop cantilever arrays as biosensors for medical diagnostic applications. MEMS cantilevers are also finding application as radio frequency filters and resonators. The MEMS cantilevers are commonly made as unimorphs or bimorphs.

Two equations are key to understanding the behavior of MEMS cantilevers. The first is Stoney's formula, which relates cantilever end deflection δ to applied stress σ:

where is Poisson's ratio, is Young's modulus, is the beam length and is the cantilever thickness. Very sensitive optical and capacitive methods have been developed to measure changes in the static deflection of cantilever beams used in dc-coupled sensors.

The second is the formula relating the cantilever spring constant to the cantilever dimensions and material constants:

where is force and is the cantilever width. The spring constant is related to the cantilever resonance frequency by the usual harmonic oscillator formula . A change in the force applied to a cantilever can shift the resonance frequency. The frequency shift can be measured with exquisite accuracy using heterodyne techniques and is the basis of ac-coupled cantilever sensors.

The principal advantage of MEMS cantilevers is their cheapness and ease of fabrication in large arrays. The challenge for their practical application lies in the square and cubic dependences of cantilever performance specifications on dimensions. These superlinear dependences mean that cantilevers are quite sensitive to variation in process parameters, particularly the thickness as this is generally difficult to accurately measure.[9] However, it has been shown that microcantilever thicknesses can be precisely measured and that this variation can be quantified.[10] Controlling residual stress can also be difficult.

Chemical sensor applications

A chemical sensor can be obtained by coating a recognition receptor layer over the upper side of a microcantilever beam.[12] A typical application is the immunosensor based on an antibody layer that interacts selectively with a particular immunogen and reports about its content in a specimen. In the static mode of operation, the sensor response is represented by the beam bending with respect to a reference microcantilever. Alternatively, microcantilever sensors can be operated in the dynamic mode. In this case, the beam vibrates at its resonance frequency and a variation in this parameter indicates the concentration of the analyte. Recently, microcantilevers have been fabricated that are porous, allowing for a much larger surface area for analyte to bind to, increasing sensitivity by raising the ratio of the analyte mass to the device mass.[13] Surface stress on microcantilever, due to receptor-target binding, which produces cantilever deflection can be analyzed using optical methods like laser interferometry. Zhao et al., also showed that by changing the attachment protocol of the receptor on the microcantilever surface, the sensitivity can be further improved when the surface stress generated on the microcantilever is taken as the sensor signal.[14]

See also

References

- ^ Hool, George A.; Johnson, Nathan Clarke (1920). "Elements of Structural Theory - Definitions". Handbook of Building Construction (Google Books). Vol. 1 (1st ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 2. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

A cantilever beam is a beam having one end rigidly fixed and the other end free.

- ^ "GMI Construction wins £5.5M Design and Build Contract for Leeds United Football Club's Elland Road East Stand". Construction News. 6 February 1992. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ IStructE The Structural Engineer Volume 77/No 21, 2 November 1999. James's Park a redevelopment challenge

- ^ highbeam.com; The Architects' Journal. Existing stadiums: St James' Park, Newcastle. 1 July 2005

- ^ Stevens, James Hay; The Shape of the Aeroplane, Hutchinson, 1953. pp.78 ff.

- ^ Davy, M.J.B.; Aeronautics – Heavier-Than-Air Aircraft, Part I, Historical Survey, Revised edition, Science Museum/HMSO, December 1949. p.57.

- ^ ELECTROMECHANICAL MONOLITHIC RESONATOR, US Pat.3417249 - Filed April 29, 1966

- ^ R.J. Wilfinger, P. H. Bardell and D. S. Chhabra: The resonistor a frequency selective device utilizing the mechanical resonance of a silicon substrate, IBM J. 12, 113–118 (1968)

- ^ P. M. Kosaka, J. Tamayo, J. J. Ruiz, S. Puertas, E. Polo, V. Grazu, J. M. de la Fuente and M. Calleja: Tackling reproducibility in microcantilever biosensors: a statistical approach for sensitive and specific end-point detection of immunoreactions, Analyst 138, 863–872 (2013)

- ^ A. R. Salmon, M. J. Capener, J. J. Baumberg and S. R. Elliott: Rapid microcantilever-thickness determination by optical interferometry, Measurement Science and Technology 25, 015202 (2014)

- ^ Patrick C. Fletcher; Y. Xu; P. Gopinath; J. Williams; B. W. Alphenaar; R. D. Bradshaw; Robert S. Keynton (2008). Piezoresistive Geometry for Maximizing Microcantilever Array Sensitivity. IEEE Sensors.

- ^ Bănică, Florinel-Gabriel (2012). Chemical Sensors and Biosensors:Fundamentals and Applications. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. p. 576. ISBN 978-1-118-35423-0.

- ^ Noyce, Steven G.; Vanfleet, Richard R.; Craighead, Harold G.; Davis, Robert C. (1999-02-22). "High surface-area carbon microcantilevers". Nanoscale Advances. 1 (3): 1148–1154. doi:10.1039/C8NA00101D. PMC 9418787. PMID 36133213.

- ^ Zhao, Yue; Gosai, Agnivo; Shrotriya, Pranav (1 December 2019). "Effect of Receptor Attachment on Sensitivity of Label Free Microcantilever Based Biosensor Using Malachite Green Aptamer". Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 300. doi:10.1016/j.snb.2019.126963.

Sources

- Inglis, Simon: Football Grounds of Britain. CollinsWillow, 1996. page 206.

- Madou, Marc J (2002). Fundamentals of Microfabrication. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-8493-0826-7.

- Roth, Leland M (1993). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements History and Meaning. Oxford, UK: Westview Press. pp. 23–4. ISBN 0-06-430158-3.

- Sarid, Dror (1994). Scanning Force Microscopy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509204-X.

External links

Media related to Cantilever beams at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cantilever beams at Wikimedia Commons