Chinese Lunar Calendar

| Chinese calendar | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 農曆 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 农历 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of science and technology in China |

|---|

|

There are various types and subtypes of the Chinese calendar and horology, which over a millennium plus history has produced many variations. The topic of the Chinese calendar includes various traditional types of the Chinese calendar, of which particularly prominent are, identifying years, months, and days according to astronomical phenomena and calculations, with generally an especial effort to correlate the solar and lunar cycles experienced on earth—but which are known to mathematically require some degree of approximation. Typical features of early calendars include the use of the sexagenary cycle-based ganzhi system's repeating cycles of Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches. The logic of the various permutations of the Chinese calendar has been based in considerations such as the technical from mathematics and astronomy, the philosophical considerations, and the political, and the resulting disparities between different calendars is significant and notable. Various similar calendar systems are also known from various regions or ethnic groups of Central Asia, South Asia, and other areas. Indeed, the Chinese calendar has influenced and been influenced by most parts of the world these days. One particularly popular feature is the Chinese zodiac. The Chinese calendar and horology includes multifaceted methods of computing years, eras, months, days and hours (with modern horology even splitting the seconds).

Epochs are one of the important features of calendar systems. An epoch is a particular point in time at which a calendar system may use as its initial time reference, allowing for the consecutive numbering of years from a chosen starting year, date, or time: this is known as an epoch, in the Chinese calendar system, examples include the inauguration of Huangdi or the birth of Confucius. Also, many dynasties had their own dating systems, which could include regnal eras based on the inauguration of a dynasty, the enthronement of a particular monarch, or eras arbitrarily designated due to political or other considerations, such as a desire for a change the luck. Era names are useful for determining dates on artifacts such as ceramics, which were often traditionally dated by an era name during the production process.

Variations of the lunisolar calendar are a particularly prominent feature of the Chinese calendar system. The topic of the Chinese calendar includes various traditional types of the Chinese calendar, of which particularly prominent are, identifying years, months, and days according to astronomical phenomena and calculations, with generally an especial effort to correlate the solar and lunar cycles experienced on earth—but which are known to mathematically require some degree of approximation. One of the major features of some traditional calendrical systems in China (and elsewhere) was the idea of the sexagenary cycle. The Chinese lunisolar calendar has had several significant variations over the course of time and history, and despite the name also considers various other astronomical phenomena besides the cycles of the sun and the moon, such as the planets and the constellations (or mansions) of asterisms along the ecliptic. Many Chinese holidays ancient and modern have been determined by a lunisolar calendar or considerations of the lunisolar calendar, now generally combined with more modern calendar considerations.

Solar and agricultural calendars have a long history in China. Purely lunar calendar systems were known in China, however they tended to be of limited utility, and were not widely accepted by farmers who for agricultural purposes needed to focus on predictability of seasons for planting and harvesting purposes and to thereby produce a useful agricultural calendar. For farming purposes and keeping track of the seasons Chinese solar calendars were particularly useful. The publication of multipurpose and agricultural almanacs has been a longstanding tradition in China.

The horology of the Chinese calendar also includes variations of the modern Chinese calendar, influenced by the Gregorian calendar. Variations include methodologies of the People's Republic of China and Taiwan.

Epochs

An epoch is a point in time chosen as the origin of a particular calendar era, thus serving as a reference point from which subsequent time or dates are measured. The use of epochs in Chinese calendar system allow for a chronological starting point from whence to begin point continuously numbering subsequent dates. Various epochs have been used. Similarly, nomenclature similar to that of the Christian era has occasionally been used:[1]

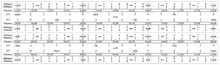

| Era | Chinese name | Start | Year 1 | 2024 CE is year... |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yellow Emperor (Huángdì) year | 黄帝紀年 | Yellow Emperor (YE) began reigning | 2697 BCE or 2698 BCE | 4721 or 4722 |

| Yáo year | 唐堯紀年 | Emperor Yao began reigning | 2156 BCE | 4180 |

| Gònghé year | 共和紀年 | Gonghe Regency began | 841 BCE | 2865 |

| Confucius year | 孔子紀年 | Confucius's birth year | 551 BCE | 2575 |

| Unity year | 統一紀年 | Qin Shi Huang began reigning | 221 BCE | 2245 |

No reference date is universally accepted. The most popular is the Gregorian calendar (公曆; 公历; gōnglì; 'common calendar').

During the 17th century, the Jesuits tried to determine the epochal year of the Han calendar. In his Sinicae historiae decas prima (published in Munich in 1658), Martino Martini (1614–1661) dated the Yellow Emperor's ascension at 2697 BCE and began the Chinese calendar with the reign of Fuxi (which, according to Martini, began in 2952 BCE). Philippe Couplet's 1686 Chronological table of Chinese monarchs (Tabula chronologica monarchiae sinicae) gave the same date for the Yellow Emperor. The Jesuits' dates provoked interest in Europe, where they were used for comparison with Biblical chronology.[citation needed] Modern Chinese chronology has generally accepted Martini's dates, except that it usually places the reign of the Yellow Emperor at 2698 BCE and omits his predecessors Fuxi and Shennong as "too legendary to include".[This quote needs a citation]

Publications began using the estimated birth date of the Yellow Emperor as the first year of the Han calendar in 1903, with newspapers and magazines proposing different dates. Jiangsu province counted 1905 as the year 4396 (using a year 1 of 2491 BCE, and implying that 2024 CE is 4515), and the newspaper Ming Pao (明報) reckoned 1905 as 4603 (using a year 1 of 2698 BCE, and implying that 2024 CE is 4722).[citation needed] Liu Shipei (劉師培, 1884–1919) created the Yellow Emperor Calendar (黃帝紀元, 黃帝曆 or 軒轅紀年), with year 1 as the birth of the emperor (which he determined as 2711 BCE, implying that 2024 CE is 4735).[2] There is no evidence that this calendar was used before the 20th century.[3] Liu calculated that the 1900 international expedition sent by the Eight-Nation Alliance to suppress the Boxer Rebellion entered Beijing in the 4611th year of the Yellow Emperor.

Taoists later adopted Yellow Emperor Calendar and named it Tao Calendar (道曆).

On 2 January 1912, Sun Yat-sen announced changes to the official calendar and era. 1 January was 14 Shíyīyuè 4609 Huángdì year, assuming a year 1 of 2698 BCE, making 2024 CE year 4722. Many overseas Chinese communities like San Francisco's Chinatown adopted the change.[4]

The modern Chinese standard calendar uses the epoch of the Gregorian calendar, which is on January 1st of the year 1 CE.

Calendar types

Lunisolar

Lunisolar calendars involve correlations of the cycles of the sun (solar) and the moon (lunar).

Solar and agricultural

A solar calendar keeps track of the seasons as the earth and the sun move in the solar system relatively to each other. A purely solar calendar may be useful in planning times for agricultural activities such as planting and harvesting. Solar calendars tend to use astronomically observable points of reference such as equinoxes and solstices, events which may be approximately predicted using fundamental methods of observation and basic mathematical analysis.

Modern Chinese calendar and horology

The topic of the Chinese calendar also includes variations of the modern Chinese calendar, influenced by the Gregorian calendar. Variations include methodologies of the People's Republic of China and Taiwan.

Modern calendars

In China, the modern calendar is defined by the Chinese national standard GB/T 33661–2017,[5][6] "Calculation and Promulgation of the Chinese Calendar", issued by the Standardization Administration of China on May 12, 2017.

Influence of Gregorian calendar

Although modern-day China uses the Gregorian calendar, the traditional Chinese calendar governs holidays, such as the Chinese New Year and Lantern Festival, in both China and overseas Chinese communities. It also provides the traditional Chinese nomenclature of dates within a year which people use to select auspicious days for weddings, funerals, moving or starting a business.[7] The evening state-run news program Xinwen Lianbo in the People's Republic of China continues to announce the months and dates in both the Gregorian and the traditional lunisolar calendar.

History

The Chinese calendar system has a long history, which has traditionally been associated with specific dynastic periods. Various individual calendar types have been developed with different names. In terms of historical development, some of the calendar variations are associated with with dynastic changes along a spectrum beginning with a prehistorical/mythological time to and through well attested historical dynastic periods. Many individuals have been associated with the development of the Chinese calendar, including researchers into underlying astronomy; and, furthermore, the development of instruments of observation are historically important. Influences from India, Islam, and Jesuits also became significant.

Chinese astronomy

The Chinese calendar has been a development involving much observation and calculation of the apparent movements of the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars, as observed from Earth.

Chinese astronomers

Many Chinese astronomers have contributed to the development of the Chinese calendar. Many were of the scholarly or shi class (Chinese: 士; pinyin: shì), including writers of history, such as Sima Qian.

Notable Chinese astronomers who have contributed to the development of the calendar include Gan De, Shi Shen, and Zu Chongzhi

Technology

Technological developments useful to the calendar system include naming, numbering and mapping of the sky, and the development of analog computational devices such as the armilla.

Chinese calendar names

There are various Chinese terms for calendar variations including:

Nongli Calendar (traditional Chinese: 農曆; simplified Chinese: 农历; pinyin: nónglì; lit. 'agricultural calendar')

Jiuli Calendar (traditional Chinese: 舊曆; simplified Chinese: 旧历; pinyin: jiùlì; Jyutping: Gau6 Lik6; lit.'former calendar')

Laoli Calendar (traditional Chinese: 老曆; simplified Chinese: 老历; pinyin: lǎolì; lit. 'old calendar')

Zhongli Calendar (traditional Chinese: 中曆; simplified Chinese: 中历; pinyin: zhōnglì; Jyutping: zung1 lik6; lit. 'Chinese calendar')

Huali Calendar (traditional Chinese: 華曆; simplified Chinese: 华历; pinyin: huálì; Jyutping: waa4 lik6; lit. 'Chinese calendar')

Solar calendars

The traditional Chinese calendar was developed between 771 and 476 BCE, during the Spring and Autumn period of the Eastern Zhou dynasty. Solar calendars were used before the Zhou dynasty period, along with the basic sexagenary system.

Five-elements calendar

One version of the solar calendar is the five-elements calendar (五行曆; 五行历), which derives from the Wu Xing. A 365-day year was divided into five phases of 73 days, with each phase corresponding to a Day 1 Wu Xing element. A phase began with a governing-element day (行御), followed by six 12-day weeks. Each phase consisted of two three-week months, making each year ten months long. Years began on a jiǎzǐ (甲子) day (and a 72-day wood phase), followed by a bǐngzǐ day (丙子) and a 72-day fire phase; a wùzǐ (戊子) day and a 72-day earth phase; a gēngzǐ (庚子) day and a 72-day metal phase, and a rénzǐ day (壬子) followed by a water phase.[8] Other days were tracked using the Yellow River Map (He Tu).

Four-quarters calendar

Another version is a four-quarters calendar (四時八節曆; 四时八节历; 'four sections', 'eight seasons calendar', or 四分曆; 四分历). The weeks were ten days long, with one month consisting of three weeks. A year had 12 months, with a ten-day week intercalated in summer as needed to keep up with the tropical year. The 10 Heavenly Stems and 12 Earthly Branches were used to mark days.[9]

Balanced calendar

A third version is the balanced calendar (調曆; 调历). A year was 365.25 days, and a month was 29.5 days. After every 16th month, a half-month was intercalated. According to oracle bone records, the Shang dynasty calendar (c. 1600 – c. 1046 BCE) was a balanced calendar with 12 to 14 months in a year; the month after the winter solstice was Zhēngyuè.[10]

Lunisolar calendar reforms by dynasty

Six ancient calendars

Modern historical knowledge and records are limited for the earlier calendars. These calendars are known as the six ancient calendars (古六曆; 古六历), or quarter-remainder calendars, (四分曆; 四分历; sìfēnlì), since all calculate a year as 365+1⁄4 days long. Months begin on the day of the new moon, and a year has 12 or 13 months. Intercalary months (a 13th month) are added to the end of the year. The Qiang and Dai calendars are modern versions of the Zhuanxu calendar, used by mountain peoples.

Zhou dynasty

The first lunisolar calendar was the Zhou calendar (周曆; 周历), introduced under the Zhou dynasty (1046 BC – 256 BCE). This calendar sets the beginning of the year at the day of the new moon before the winter solstice.

Competing Warring states calendars

Several competing lunisolar calendars were also introduced as Zhou devolved into the Warring States, especially by states fighting Zhou control during the Warring States period (perhaps 475-221 BCE). The state of Lu issued its own Lu calendar(魯曆; 鲁历). Jin issued the Xia calendar (夏曆; 夏历)[11] with a year beginning on the day of the new moon nearest the March equinox. Qin issued the Zhuanxu calendar (顓頊曆; 颛顼历), with a year beginning on the day of the new moon nearest the winter solstice. Song's Yin calendar (殷曆; 殷历) began its year on the day of the new moon after the winter solstice.

Qin and early Han dynasties

After Qin Shi Huang unified China under the Qin dynasty in 221 BCE, the Qin calendar (秦曆; 秦历) was introduced. It followed most of the rules governing the Zhuanxu calendar, but the month order was that of the Xia calendar; the year began with month 10 and ended with month 9, analogous to a Gregorian calendar beginning in October and ending in September. The intercalary month, known as the second Jiǔyuè (後九月; 后九月; 'later Jiǔyuè'), was placed at the end of the year. The Qin calendar was used going into the Han dynasty.

Han dynasty Tàichū calendar

Emperor Wu of Han r. 141 – 87 BCE introduced reforms in the seventh of the eleven named eras of his reign, Tàichū (Chinese: 太初; pinyin: Tàichū; lit. 'Grand Beginning'), 104 BC – 101 BCE. His Tàichū Calendar (太初曆; 太初历; 'grand beginning calendar') defined a solar year as 365+385⁄1539 days, and the lunar month had 29+43⁄81 days. Since the 19 years cycle used for the 7 additional months was taken as an exact one, and not as an approximation.

This calendar introduced the 24 solar terms, dividing the year into 24 equal parts. Solar terms were paired, with the 12 combined periods known as climate terms. The first solar term of the period was known as a pre-climate (节气), and the second was a mid-climate (中气). Months were named for the mid-climate to which they were closest, and a month without a mid-climate was an intercalary month.[citation needed]

The Taichu calendar established a framework for traditional calendars, with later calendars adding to the basic formula.

Northern and Southern Dynasties Dàmíng calendar

The Dàmíng Calendar (大明曆; 大明历; 'brightest calendar'), created in the Northern and Southern Dynasties by Zu Chongzhi (429–500 AD), introduced the equinoxes.

Tang dynasty Wùyín Yuán calendar

The use of syzygy to determine the lunar month was first described in the Tang dynasty Wùyín Yuán Calendar (戊寅元曆; 戊寅元历; 'earth tiger epoch calendar').

Yuan dynasty Shòushí calendar

The Yuan dynasty Shòushí calendar (授時曆; 授时历; 'season granting calendar') used spherical trigonometry to find the length of the tropical year.[12][13][14] The calendar had a 365.2425-day year, identical to the Gregorian calendar.[15]

Although the Chinese calendar lost its place as the country's official calendar at the beginning of the 20th century,[16] its use has continued. The Republic of China Calendar published by the Beiyang government of the Republic of China still listed the dates of the Chinese calendar in addition to the Gregorian calendar. In 1929, the Nationalist government tried to ban the traditional Chinese calendar. The Kuómín Calendar published by the government no longer listed the dates of the Chinese calendar. However, Chinese people were used to the traditional calendar and many traditional customs were based on the Chinese calendar. The ban failed and was lifted in 1934.[17] The latest Chinese calendar was "New Edition of Wànniánlì, revised edition", edited by Beijing Purple Mountain Observatory, People's Republic of China.[18]

Shíxiàn calendar

From 1645 to 1913 the Shíxiàn or Chongzhen was developed. During the late Ming dynasty, the Chinese Emperor appointed Xu Guangqi in 1629 to be the leader of the ShiXian calendar reform. Assisted by Jesuits, he translated Western astronomical works and introduced new concepts, such as those of Nicolaus Copernicus, Johannes Kepler, Galileo Galilei, and Tycho Brahe; however, the new calendar was not released before the end of the dynasty. In the early Qing dynasty, Johann Adam Schall von Bell submitted the calendar which was edited by the lead of Xu Guangqi to the Shunzhi Emperor.[19] The Qing government issued it as the Shíxiàn (seasonal) calendar. In this calendar, the solar terms are 15° each along the ecliptic and it can be used as a solar calendar. However, the length of the climate term near the perihelion is less than 30 days and there may be two mid-climate terms. The Shíxiàn calendar changed the mid-climate-term rule to "decide the month in sequence, except the intercalary month."[20] The present traditional calendar follows the Shíxiàn calendar, except:

- The baseline is Chinese Standard Time, rather than Beijing local time.

- (Modern) astronomical data, rather than mathematical calculations, is used.

Proposals

To optimize the Chinese calendar, astronomers have proposed a number of changes. Gao Pingzi (高平子; 1888–1970), a Chinese astronomer who co-founded the Purple Mountain Observatory, proposed that month numbers be calculated before the new moon and solar terms to be rounded to the day. Since the intercalary month is determined by the first month without a mid-climate and the mid-climate time varies by time zone, countries that adopted the calendar but calculate with their own time could vary from the time in China.[21]

Horology

Horologic definitions

Days begin and end at midnight, and months begin on the day of the new moon. Years start on the second (or third) new moon after the winter solstice. Solar terms govern the beginning, middle, and end of each month. A sexagenary cycle, comprising the heavenly stems (Chinese: 干; pinyin: gān) and the earthly branches (Chinese: 支; pinyin: zhī), is used as identification alongside each year and month, including intercalary months or leap months. Months are also annotated as either long (Chinese: 大; lit. 'big' for months with 30 days) or short (Chinese: 小; lit. 'small' for months with 29 days).

Elements

The traditional Chinese calendar's elements are:

- Day (日; rì), from one midnight to the next

- Month (月; yuè), the time from one new moon to the next. These synodic months are about 29+17⁄32 days long.

- Date (日期; rìqī), when a day occurs in the month. Days are numbered in sequence from 1 to 29 (or 30).

- Year (年; nián), time of one revolution of Earth around the Sun. It is measured from the first day of spring (lunisolar year) or the winter solstice (solar year). A year is about 365+31⁄128 days.

- Zodiac, 1⁄12 year, or 30° on the ecliptic. A zodiac is about 30+7⁄16 days.

- Solar term (節氣; jiéqì), 1⁄24 year, or 15° on the ecliptic. A solar term is about 15+7⁄32 days.

- Calendar month (日曆月; rìlì yuè), when a month occurs within a year. Some months may be repeated.

- Calendar year (日曆月年; rìlì nián), when it is agreed that one year ends and another begins. The year usually begins on the new moon closest to Lichun, the first day of spring.[4] This is typically the second and sometimes third new moon after the winter solstice. A calendar year is 353–355 or 383–385 days long.

The Chinese calendar is lunisolar, similar to the Hindu, Hebrew and ancient Babylonian calendars.

Planets

The movements of the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn (known as the seven luminaries) are the references for calendar calculations.

- The distance between Mercury and the sun is less than 30° (the sun's height at chénshí:辰時, 8:00 to 10:00 am), so Mercury was sometimes called the "chen star" (辰星); it is more commonly known as the "water star" (水星).

- Venus appears at dawn and dusk and is known as the "bright star" (啟明星; 启明星) or "long star" (長庚星; 长庚星).

- Mars looks like fire and occurs irregularly, and is known as the "fire star" (熒惑星; 荧惑星 or 火星). Mars is the punisher in Chinese mythology. When Mars is near Antares (心宿二), it is a bad omen and can forecast an emperor's death or a chancellor's removal (荧惑守心).

- Jupiter's revolution period is 11.86 years, so Jupiter is called the "age star" (歲星; 岁星); 30° of Jupiter's revolution is about a year on earth.

- Saturn's revolution period is about 28 years. Known as the "guard star" (鎮星), Saturn guards one of the 28 Mansions every year.

Big Dipper

The Big Dipper is the celestial compass, and its handle's direction indicates or some said determines the season and month.

3 Enclosures and 28 Mansions

The stars are divided into Three Enclosures and 28 Mansions according to their location in the sky relative to Ursa Minor, at the center. Each mansion is named with a character describing the shape of its principal asterism. The Three Enclosures are Purple Forbidden, (紫微), Supreme Palace (太微), and Heavenly Market. (天市) The eastern mansions are 角, 亢, 氐, 房, 心, 尾, 箕. Southern mansions are 井, 鬼, 柳, 星, 張, 翼, 轸. Western mansions are 奎, 婁, 胃, 昴, 畢, 參, 觜. Northern mansions are 斗, 牛, 女, 虛, 危, 室, 壁. The moon moves through about one lunar mansion per day, so the 28 mansions were also used to count days. In the Tang dynasty, Yuan Tiangang (袁天罡) matched the 28 mansions, seven luminaries and yearly animal signs to yield combinations such as "horn-wood-flood dragon" (角木蛟).

List of lunar mansions

The names and determinative stars of the mansions are:[22][23]

| Four Symbols (四象) |

Mansion (宿) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Name

(Pinyin) |

Translation | Determinative star | |

| Azure Dragon of the East (東方青龍 - Dōngfāng Qīnglóng) Spring  |

1 | 角 (Jiǎo) | Horn | α Vir |

| 2 | 亢 (Kàng) | Neck | κ Vir | |

| 3 | 氐 (Dī) | Root | α Lib | |

| 4 | 房 (Fáng) | Room | π Sco | |

| 5 | 心 (Xīn) | Heart | α Sco | |

| 6 | 尾 (Wěi) | Tail | μ¹ Sco | |

| 7 | 箕 (Jī) | Winnowing Basket | γ Sgr | |

| Black Tortoise of the North (北方玄武 - Běifāng Xuánwǔ) Winter  |

8 | 斗 (Dǒu) | (Southern) Dipper | φ Sgr |

| 9 | 牛 (Niú) | Ox | β Cap | |

| 10 | 女 (Nǚ) | Girl | ε Aqr | |

| 11 | 虛 (Xū) | Emptiness | β Aqr | |

| 12 | 危 (Wēi) | Rooftop | α Aqr | |

| 13 | 室 (Shì) | Encampment | α Peg | |

| 14 | 壁 (Bì) | Wall | γ Peg | |

| White Tiger of the West (西方白虎 - Xīfāng Báihǔ) Fall  |

15 | 奎 (Kuí) | Legs | η And |

| 16 | 婁 (Lóu) | Bond | β Ari | |

| 17 | 胃 (Wèi) | Stomach | 35 Ari | |

| 18 | 昴 (Mǎo) | Hairy Head | 17 Tau | |

| 19 | 畢 (Bì) | Net | ε Tau | |

| 20 | 觜 (Zī) | Turtle Beak | λ Ori | |

| 21 | 参 (Shēn) | Three Stars | ζ Ori | |

| Vermilion Bird of the South (南方朱雀 - Nánfāng Zhūquè) Summer  |

22 | 井 (Jǐng) | Well | μ Gem |

| 23 | 鬼 (Guǐ) | Ghost | θ Cnc | |

| 24 | 柳 (Liǔ) | Willow | δ Hya | |

| 25 | 星 (Xīng) | Star | α Hya | |

| 26 | 張 (Zhāng) | Extended Net | υ¹ Hya | |

| 27 | 翼 (Yì) | Wings | α Crt | |

| 28 | 軫 (Zhěn) | Chariot | γ Crv | |

Descriptive mathematics

Several coding systems are used to avoid ambiguity. The Heavenly Stems is a decimal system. The Earthly Branches, a duodecimal system, mark dual hours (時; 时; shí or 時辰; 时辰; shíchen) and climatic terms. The 12 characters progress from the first day with the same branch as the month (first Yín day (寅日) of Zhēngyuè; first Mǎo day (卯日) of Èryuè), and count the days of the month.

The stem-branches is a sexagesimal system. The Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches make up 60 stem-branches. The stem branches mark days and years. The five Wu Xing elements are assigned to each stem, branch, or stem branch.

| Heavenly Stem |

Meaning | |

|---|---|---|

| Original meaning | Modern | |

| 甲 | turtle shell | first (book I, person A etc.), methyl group, helmet, armor, words related to beetles, crustaceans, fingernails, toenails |

| 乙 | fishguts | second (book II, person B etc.), ethyl group, twist |

| 丙 | fishtail[24] | third, bright, fire, fishtail (rare) |

| 丁 | nail | fourth, male adult, robust, T-shaped, to strike, a surname |

| 戊 | halberd | (not used) |

| 己 | threads on a loom[25] | self |

| 庚 | evening star | age (of person) |

| 辛 | to offend superiors[26] | bitter, piquant, toilsome |

| 壬 | burden[27] | to shoulder, to trust with office |

| 癸 | grass for libation[28] | (not used) |

Twelve branches

| Earthly Branch |

Chinese | Direction | Season | Lunar Month | Double Hour | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandarin Zhuyin |

Mandarin Pinyin | |||||||

| 1 | 子 | ㄗˇ | zǐ | 鼠 Rat |

0° (north) | winter | Month 11 | 11pm to 1am (midnight) |

| 2 | 丑 | ㄔㄡˇ | chǒu | 牛 Cow |

30° | Month 12 | 1am to 3am | |

| 3 | 寅 | ㄧㄣˊ | yín | 虎 Tiger |

60° | spring | Month 1 | 3am to 5am |

| 4 | 卯 | ㄇㄠˇ | mǎo | 兎 Rabbit |

90° (east) | Month 2 | 5am to 7am | |

| 5 | 辰 | ㄔㄣˊ | chén | 竜 (龍) Dragon |

120° | Month 3 | 7am to 9 am | |

| 6 | 巳 | ㄙˋ | sì | 蛇 Snake |

150° | summer | Month 4 | 9am to 11am |

| 7 | 午 | ㄨˇ | wǔ | 馬 Horse |

180° (south) | Month 5 | 11am to 1pm (noon) | |

| 8 | 未 | ㄨㄟˋ | wèi | 羊 Sheep |

210° | Month 6 | 1pm to 3pm | |

| 9 | 申 | ㄕㄣ | shēn | 猿 Monkey |

240° | autumn | Month 7 | 3pm to 5pm |

| 10 | 酉 | ㄧㄡˇ | yǒu | 鶏 (鳥) Chicken |

270° (west) | Month 8 | 5pm to 7pm | |

| 11 | 戌 | ㄒㄩ | xū | 犬 Dog |

300° | Month 9 | 7pm to 9pm | |

| 12 | 亥 | ㄏㄞˋ | hài | 猪 Wild boar |

330° | winter | Month 10 | 9pm to 11pm |

Day

China has used the Western hour-minute-second system to divide the day since the Qing dynasty.[29] Several era-dependent systems had been in use; systems using multiples of twelve and ten were popular, since they could be easily counted and aligned with the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches.

Week

As early as the Bronze Age Xia dynasty, days were grouped into nine- or ten-day weeks known as xún (旬).[30] Months consisted of three xún. The first 10 days were the early xún (上旬), the middle 10 the mid xún (中旬), and the last nine (or 10) days were the late xún (下旬). Japan adopted this pattern, with 10-day-weeks known as jun (旬). In Korea, they were known as sun (순,旬).

The structure of xún led to public holidays every five or ten days. Officials of the Han dynasty were legally required to rest every five days (twice a xún, or 5–6 times a month). The name of these breaks became huan (澣; 浣, "wash").

Grouping days into sets of ten is still used today in referring to specific natural events. "Three Fu" (三伏), a 29–30-day period which is the hottest of the year, reflects its three-xún length.[31] After the winter solstice, nine sets of nine days were counted to calculate the end of winter.[32]

The seven-day week was adopted from the Hellenistic system by the 4th century AD[citation needed], although its method of transmission into China is unclear. It was again transmitted to China in the 8th century by Manichaeans via Kangju (a Central Asian kingdom near Samarkand),[33][a][b] and is the most-used system in modern China.

Month

Months are defined by the time between new moons, which averages approximately 29+17⁄32 days. There is no specified length of any particular Chinese month, so the first month could have 29 days (short month, 小月) in some years and 30 days (long month, 大月) in other years.

A 12-month-year using this system has 354 days, which would drift significantly from the tropical year. To fix this, traditional Chinese years have a 13-month year approximately once every three years. The 13-month version has the same long and short months alternating, but adds a 30-day leap month (閏月; rùnyuè). Years with 12 months are called common years, and 13-month years are known as long years.

Although most of the above rules were used until the Tang dynasty, different eras used different systems to keep lunar and solar years aligned. The synodic month of the Taichu calendar was 29+43⁄81 days long. The 7th-century, Tang-dynasty Wùyín Yuán Calendar was the first to determine month length by synodic month instead of the cycling method. Since then, month lengths have primarily been determined by observation and prediction.

The days of the month are always written with two characters and numbered beginning with 1. Days one to 10 are written with the day's numeral, preceded by the character Chū (初); Chūyī (初一) is the first day of the month, and Chūshí (初十) the 10th. Days 11 to 20 are written as regular Chinese numerals; Shíwǔ (十五) is the 15th day of the month, and Èrshí (二十) the 20th. Days 21 to 29 are written with the character Niàn (廿) before the characters one through nine; Niànsān (廿三), for example, is the 23rd day of the month. Day 30 (when applicable) is written as the numeral Sānshí (三十).

History books use days of the month numbered with the 60 stem-branches:

天聖元年…二月…丁巳,奉安太祖、太宗御容于南京鴻慶宮.

Tiānshèng 1st year…Èryuè…Dīngsì, the emperor's funeral was at his temple, and the imperial portrait was installed in Nanjing's Hongqing Palace.

Because astronomical observation determines month length, dates on the calendar correspond to moon phases. The first day of each month is the new moon. On the seventh or eighth day of each month, the first-quarter moon is visible in the afternoon and early evening. On the 15th or 16th day of each month, the full moon is visible all night. On the 22nd or 23rd day of each month, the last-quarter moon is visible late at night and in the morning.

Since the beginning of the month is determined by when the new moon occurs, other countries using this calendar use their own time standards to calculate it; this results in deviations. The first new moon in 1968 was at 16:29 UTC on 29 January. Since North Vietnam used UTC+07:00 to calculate their Vietnamese calendar and South Vietnam used UTC+08:00 (Beijing time) to calculate theirs, North Vietnam began the Tết holiday at 29 January at 23:29 while South Vietnam began it on 30 January at 00:15. The time difference allowed asynchronous attacks in the Tet Offensive.[4]

Names of months

Lunar months were originally named according to natural phenomena. Current naming conventions use numbers as the month names. Every month is also associated with one of the twelve Earthly Branches.

| Month number | Starts on Gregorian date | Phenological name | Earthly Branch name | Modern name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | between 21 January – 20 February * | 陬月; zōuyuè; 'corner month'. square of Pegasus month | 寅月; yínyuè; 'tiger month' | 正月; zhēngyuè; 'first month' |

| 2 | between 20 February – 21 March * | 杏月; xìngyuè; 'apricot month' | 卯月; mǎoyuè; 'rabbit month' | 二月; èryuè; 'second month' |

| 3 | between 21 March – 20 April * | 桃月; táoyuè; 'peach month' | 辰月; chényuè; 'dragon month' | 三月; sānyuè; 'third month' |

| 4 | between 20 April – 21 May * | 梅月; méiyuè; 'plum month' | 巳月; sìyuè; 'snake month' | 四月; sìyuè; 'fourth month' |

| 5 | between 21 May – 21 June * | 榴月; liúyuè; 'pomegranate month' | 午月; wǔyuè; 'horse month' | 五月; wǔyuè; 'fifth month' |

| 6 | between 21 June – 23 July * | 荷月; héyuè; 'lotus month' | 未月; wèiyuè; 'goat month' | 六月; liùyuè; 'sixth month' |

| 7 | between 23 July – 23 August * | 蘭月; 兰月; lányuè; 'orchid month' | 申月; shēnyuè; 'monkey month' | 七月; qīyuè; 'seventh month' |

| 8 | between 23 August – 23 September * | 桂月; guìyuè; 'osmanthus month' | 酉月; yǒuyuè; 'rooster month' | 八月; bāyuè; 'eighth month' |

| 9 | between 23 September – 23 October * | 菊月; júyuè; 'chrysanthemum month' | 戌月; xūyuè; 'dog month' | 九月; jiǔyuè; 'ninth month' |

| 10 | between 23 October – 22 November * | 露月; lùyuè; 'dew month' | 亥月; hàiyuè; 'pig month' | 十月; shíyuè; 'tenth month' |

| 11 | between 22 November – 22 December * | 冬月; dōngyuè; 'winter month'; 葭月; jiāyuè; 'reed month' | 子月; zǐyuè; 'rat month' | 冬月; dōngyuè; 'eleventh month' |

| 12 | between 22 December – 21 January * | 冰月; bīngyuè; 'ice month' | 丑月; chǒuyuè; 'ox month' | 臘月; 腊月; làyuè; 'end-of-year month' |

- Gregorian dates are approximate and should be used with caution. Many years have intercalary months.

Chinese lunar date conventions

Though the numbered month names are often used for the corresponding month number in the Gregorian calendar, it is important to realize that the numbered month names are not interchangeable with the Gregorian months when talking about lunar dates.

- Incorrect: The Dragon Boat Festival falls on 5 May in the Lunar Calendar, whereas the Double Ninth Festival, Lantern Festival, and Qixi Festival fall on 9 September, 15 January, and 7 July in the Lunar Calendar, respectively.

- Correct: The Dragon Boat Festival falls on Wǔyuè 5th (or, 5th day of the fifth month) in the Lunar Calendar, whereas the Double Ninth Festival, Lantern Festival and Qixi Festival fall on Jiǔyuè 9th (or, 9th day of the ninth month), Zhēngyuè 15th (or, 15th day of the first month) and Qīyuè 7th (or, 7th day of the seventh month) in the Lunar Calendar, respectively.

- Alternate Chinese Zodiac correction: The Dragon Boat Festival falls on Horse Month 5th in the Lunar Calendar, whereas the Double Ninth Festival, Lantern Festival and Qixi Festival fall on Dog Month 9th, Tiger Month 15th and Monkey Month 7th in the Lunar Calendar, respectively.

One may identify the heavenly stem and earthly branch corresponding to a particular day in the month, and those corresponding to its month, and those to its year, to determine the Four Pillars of Destiny associated with it, for which the Tung Shing, also referred to as the Chinese Almanac of the year, or the Huangli, and containing the essential information concerning Chinese astrology, is the most convenient publication to consult. Days rotate through a sexagenary cycle marked by coordination between heavenly stems and earthly branches, hence the referral to the Four Pillars of Destiny as, "Bazi", or "Birth Time Eight Characters", with each pillar consisting of a character for its corresponding heavenly stem, and another for its earthly branch. Since Huangli days are sexagenaric, their order is quite independent of their numeric order in each month, and of their numeric order within a week (referred to as True Animals in relation to the Chinese zodiac). Therefore, it does require painstaking calculation for one to arrive at the Four Pillars of Destiny of a particular given date, which rarely outpaces the convenience of simply consulting the Huangli by looking up its Gregorian date.

Solar term

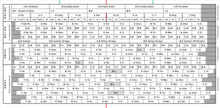

The solar year (歲; 岁; Suì), the time between winter solstices, is divided into 24 solar terms known as jié qì (節氣). Each term is a 15° portion of the ecliptic. These solar terms mark both Western and Chinese seasons, as well as equinoxes, solstices, and other Chinese events. The even solar terms (marked with "Z", for Chinese: 中氣, Zhongqi) are considered the major terms, while the odd solar terms (marked with "J", for Chinese: 節氣, Jieqi) are deemed minor.[34] The solar terms qīng míng (清明) on 5 April and dōng zhì (冬至) on 22 December are both celebrated events in China.[34]

| Number | Name | Chinese marker | Event | Approximate Date | Corresponding Astrological Sign |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J1 | Lì chūn | 立春 | Beginning of spring | 5 February | |

| Z1 | Yǔ shuǐ | 雨水 | Rain water | 19 February | Pisces |

| J2 | Jīng zhé | 驚蟄;惊蛰 | Waking of insects | 6 March | |

| Z2 | Chūn fēn | 春分 | Spring divide | 21 March | Aries |

| J3 | Qīng míng | 清明 | Pure brightness | 5 April | |

| Z3 | Gǔ yǔ | 穀雨;谷雨 | Grain rain | 20 April | Taurus |

| J4 | Lì xià | 立夏 | Beginning of summer | 6 May | |

| Z4 | Xiǎo mǎn | 小滿;小满 | Grain full | 21 May | Gemini |

| J5 | Máng zhòng | 芒種;芒种 | Grain in ear | 6 June | |

| Z5 | Xià zhì | 夏至 | Summer extremity | 22 June | Cancer |

| J6 | Xiǎo shǔ | 小暑 | Slight heat | 7 July | |

| Z6 | Dà shǔ | 大暑 | Great heat | 23 July | Leo |

| J7 | Lì qiū | 立秋 | Beginning of autumn | 8 August | |

| Z7 | Chǔ shǔ | 處暑;处署 | Limit of heat | 23 August | Virgo |

| J8 | Bái lù | 白露 | White dew | 8 September | |

| Z8 | Qiū fēn | 秋分 | Autumn divide | 23 September | Libra |

| J9 | Hán lù | 寒露 | Cold dew | 8 October | |

| Z9 | Shuāng jiàng | 霜降 | Descent of frost | 24 October | Scorpio |

| J10 | Lì dōng | 立冬 | Beginning of winter | 8 November | |

| Z10 | Xiǎo xuě | 小雪 | Slight snow | 22 November | Sagittarius |

| J11 | Dà xuě | 大雪 | Great snow | 7 December | |

| Z11 | Dōng zhì | 冬至 | Winter extremity | 22 December | Capricorn |

| J12 | Xiǎo hán | 小寒 | Slight cold | 6 January | |

| Z12 | Dà hán | 大寒 | Great cold | 20 January | Aquarius |

Solar year

The calendar solar year, known as the suì, (歲; 岁) begins on the December solstice and proceeds through the 24 solar terms.[34] Since the speed of the Sun's apparent motion in the elliptical is variable, the time between major solar terms is not fixed. This variation in time between major solar terms results in different solar year lengths. There are generally 11 or 12 complete months, plus two incomplete months around the winter solstice, in a solar year. The complete months are numbered from 0 to 10, and the incomplete months are considered the 11th month. If there are 12 complete months in the solar year, it is known as a leap solar year, or leap suì[34].

Due to the inconsistencies in the length of the solar year, different versions of the traditional calendar might have different average solar year lengths. For example, one solar year of the 1st century BCE Tàichū calendar is 365+385⁄1539 (365.25016) days. A solar year of the 13th-century Shòushí calendar is 365+97⁄400 (365.2425) days, identical to the Gregorian calendar. The additional .00766 day from the Tàichū calendar leads to a one-day shift every 130.5 years.

Pairs of solar terms are climate terms, or solar months. The first solar term is "pre-climate" (節氣; 节气; Jiéqì), and the second is "mid-climate" (中氣; 中气; Zhōngqì).

If there are 12 complete months within a solar year,[35] the first month without a mid-climate is the leap, or intercalary, month. In other words, the first month that does not include a major solar term is the leap month.[34] Leap months are numbered with rùn 閏, the character for "intercalary", plus the name of the month they follow. In 2017, the intercalary month after month six was called Rùn Liùyuè, or "intercalary sixth month" (閏六月) and written as 6i or 6+. The next intercalary month (in 2020, after month four) will be called Rùn Sìyuè (閏四月) and written 4i or 4+.

Lunisolar year

The lunisolar year begins with the first spring month, Zhēngyuè (正月; 'capital month'), and ends with the last winter month, Làyuè (臘月; 腊月; 'sacrificial month'). All other months are named for their number in the month order. See below on the timing of the Chinese New Year.

Years were traditionally numbered by the reign in ancient China, but this was abolished after founding the People's Republic of China in 1949. For example, the year from 12 February 2021 to 31 January 2022 was a Xīnchǒu year (辛丑年) of 12 months or 354 days.

The Tang dynasty used the Earthly Branches to mark the months from December 761 to May 762.[36] Over this period, the year began with the winter solstice.

Age reckoning

In China, a person's official age is based on the Gregorian calendar. For traditional use, age is based on the Chinese Sui calendar. A child is considered one year old a hundred days after birth (9 months gestation plus 3 months). After each Chinese New Year, one year is added to their traditional age. Their age therefore is the number of Chinese years which have passed. Due to the potential for confusion, the age of infants is often given in months instead of years.

After the Gregorian calendar was introduced in China, the Chinese traditional-age was referred to as the "nominal age" (虛歲; 虚岁; xūsuì; 'incomplete age') and the Gregorian age was known as the "real age" (實歲; 实岁; shísùi; 'whole age').

Year-numbering systems

Eras

Ancient China numbered years from an emperor's ascension to the throne or his declaration of a new era name. The first recorded reign title was Jiànyuán (建元), from 140 BCE; the last reign title was Xuāntǒng (宣統; 宣统), from 1908 CE. The era system was abolished in 1912, after which the current or Republican era was used.

Stem-branches

The 60 stem-branches have been used to mark the date since the Shang dynasty (1600–1046 BC). Astrologers knew that the orbital period of Jupiter is about 12×361 = 4332 days, which they divided period into 12 years (歲; 岁; suì) of 361 days each. The stem-branches system solved the era system's problem of unequal reign lengths.

Chinese New Year

The date of the Chinese New Year accords with the patterns of the lunisolar calendar and hence is variable from year to year.

The invariant between years is that the winter solstice, Dongzhi is required to be in the eleventh month of the year.[37]: 313 This means that Chinese New Year will be on the second new moon after the previous winter solstice, unless there is a leap month 11 or 12 in the previous year.[4]: 31–32 [37]: 313–316

This rule is accurate, however there are two other mostly (but not completely) accurate rules that are commonly stated:[4]: 31–32 [34]

- The new year is on the new moon closest to Lichun (typically 4 February).

- The new year is on the first new moon after Dahan (typically 20 January)

It has been found that Chinese New Year moves back by either 10, 11, or 12 days in most years. If it falls on or before 31 January, then it moves forward in the next year by either 18, 19, or 20 days.[34]

Phenology

Phenology is the study of periodic events in biological life cycles and how these are influenced by seasonal and interannual variations in climate, as well as habitat factors (such as elevation).[38] The plum-rains season (梅雨), the rainy season in late spring and early summer, begins on the first bǐng day after Mangzhong (芒種) and ends on the first wèi day after Xiaoshu (小暑). The Three Fu (三伏; sānfú) are three periods of hot weather, counted from the first gēng day after the summer solstice. The first fu (初伏; chūfú) is 10 days long. The mid-fu (中伏; zhōngfú) is 10 or 20 days long. The last fu (末伏; mòfú) is 10 days from the first gēng day after the beginning of autumn.[31] The Shujiu cold days (數九; shǔjǐu; 'counting to nine') are the 81 days after the winter solstice (divided into nine sets of nine days), and are considered the coldest days of the year. Each nine-day unit is known by its order in the set, followed by "nine" (九).[39] In traditional Chinese culture, "nine" represents the infinity, which is also the number of "Yang". People believe that the nine times accumulation of "Yang" gradually reduces the "Yin", and finally the weather becomes warm.[40]

Common holidays based on the Chinese (lunisolar) calendar

Various traditional and religious holidays shared by communities throughout the world use the Chinese (Lunisolar) calendar:

Holidays with the same day and same month

The Chinese New Year (known as the Spring Festival/春節 in China) is on the first day of the first month and was traditionally called the Yuan Dan (元旦) or Zheng Ri (正日). In Vietnam it is known as Tết Nguyên Đán (節元旦), and in Korea it is known as 설날. Traditionally it was the most important holiday of the year. It is an official holiday in China, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, Vietnam, Korea, the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, and Mauritius. It is also a public holiday in Thailand's Narathiwat, Pattani, Yala and Satun provinces, and is an official public school holiday in New York City.

The Double Third Festival is on the third day of the third month and in Korea is known as 삼짇날 (samjinnal).

The Dragon Boat Festival, or the Duanwu Festival (端午節), is on the fifth day of the fifth month and is an official holiday in China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. It is also celebrated in Vietnam where it is known as Tết Đoan Ngọ (節端午) and in Korea where it is known as 단오 (端午) (Dano) or 수릿날 (戌衣日/水瀨日) (surinal) (both Hanja are used as they are homonyms).

The Qixi Festival (七夕節) is celebrated in the evening of the seventh day of the seventh month. It is also celebrated in Vietnam where it is known as Thất tịch (七夕) and in Korea where is known as 칠석 (七夕) (chilseok).

The Double Ninth Festival (重陽節) is celebrated on the ninth day of the ninth month. It is also celebrated in Vietnam where it is known as Tết Trùng Cửu (節重九) and in Korea where it is known as 중양절 (jungyangjeol).

Full moon holidays (holidays on the fifteenth day)

The Lantern Festival is celebrated on the fifteenth day of the first month and was traditionally called the Yuan Xiao (元宵) or Shang Yuan Festival (上元節). In Vietnam, it is known as Tết Thượng Nguyên (節上元) and in Korea, it is known as 대보름 (大보름) Daeboreum (or the Great Full Month).

The Zhong Yuan Festival is celebrated on the fifteenth day of the seventh month. In Vietnam, it is celebrated as Tết Trung Nguyên (中元節) or Lễ Vu Lan (禮盂蘭) and in Korea it is known as 백중 (百中/百種) Baekjong or 망혼일 (亡魂日) Manghongil (Deceased Spirit Day) or 중원 (中元) Jungwon.

The Mid-Autumn Festival is celebrated on the fifteenth day of the eighth month. In Vietnam, it is celebrated as Tết Trung Thu (節中秋) and in Korea it is known as 추석 (秋夕) Chuseok.

The Xia Yuan Festival is celebrated on the fifteenth day of the tenth month. In Vietnam, it is celebrated as Tết Hạ Nguyên (節下元).

Celebrations of the twelfth month

The Laba Festival is on the eighth day of the twelfth month. It is the enlightenment day of Sakyamuni Buddha and is celebrated in Korea as 성도재일 (seongdojaeil) and in Vietnam is known as Lễ Vía Phật Thích Ca Thành Đạo.

The Kitchen God Festival is celebrated on the twenty-third day of the twelfth month in northern regions of China and on the twenty-fourth day of the twelfth month in southern regions of China.

Chinese New Year's Eve is also known as the Chuxi Festival and is celebrated on the evening of the last day of the lunar calendar. It is celebrated wherever the lunar calendar is observed.

Celebrations of solar-term holidays

The Qingming Festival (清明节) is celebrated on the fifteenth day after the Spring Equinox. It is celebrated in Vietnam as Tết Thanh Minh (節清明).

The Dongzhi Festival (冬至) or the Winter Solstice is celebrated as Lễ hội Đông Chí (禮會冬至) in Vietnam and as 동지 (冬至) in Korea.

Religious holidays based on the lunar calendar

East Asian Mahayana, Daoist, and some Cao Dai holidays and/or vegetarian observances are based on the Lunar Calendar.[41][42][43]

Celebrations in Japan

Many of the above holidays of the lunar calendar are also celebrated in Japan, but since the Meiji era on the similarly numbered dates of the Gregorian calendar.

Double celebrations due to intercalary months

In the case when there is a corresponding intercalary month, the holidays may be celebrated twice. For example, in the hypothetical situation in which there is an additional intercalary seventh month, the Zhong Yuan Festival will be celebrated in the seventh month followed by another celebration in the intercalary seventh month.

Similar calendars

Like Chinese characters, variants of the Chinese calendar have been used in different parts of the Sinosphere throughout history.

Outlying areas of China

Calendars of ethnic groups in mountains and plateaus of southwestern China and grasslands of northern China are based on their phenology and algorithms of traditional calendars of different periods, particularly the Tang and pre-Qin dynasties.[44]

Non-Chinese areas

Korea, Vietnam, and the Ryukyu Islands adopted the Chinese calendar. In the respective regions, the Chinese calendar has been adapted into the Korean, Vietnamese, and Ryukyuan calendars, with the main difference from the Chinese calendar being the use of different meridians due to geography, leading to some astronomical events — and calendar events based on them — falling on different dates. The traditional Japanese calendar was also derived from the Chinese calendar (based on a Japanese meridian), but Japan abolished its official use in 1873 after Meiji Restoration reforms. Calendars in Mongolia[45] and Tibet[citation needed] have absorbed elements of the traditional Chinese calendar but are not direct descendants of it.

See also

- Chinese astrology

- Chinese astronomy

- Chinese calendar correspondence table

- Chinese culture

- Chinese zodiac

- Chinese numerals

- East Asian age reckoning

- Guo Shoujing, an astronomer tasked with calendar reform during the 13th century

- Horology

- List of festivals in China

- List of festivals in Asia

- Public holidays in China

- Traditional Chinese timekeeping

- Chinese era name

- Metonic cycle of 19 years is used to reckon leap years with intercalary months in the Hebrew and Babylonian calendars

Notes

- ^ The 4th-century date, according to the Cihai encyclopedia,[year needed] is due to a reference to Fan Ning (範寧; 范宁), an astrologer of the Jin dynasty.[full citation needed]

- ^ The renewed adoption from Manichaeans by the 8th century (Tang dynasty) is documented by the writings of the Chinese Buddhist monk Yi Jing and the Ceylonese Buddhist monk Bu Kong.[full citation needed]

References

- ^ Liu, Rong (2004). "[Subsidiary Relations in the Pre-Qin Period](春秋依附关系探讨)". 辽宁大学学报:哲社版 Journal of Liaoning University: Philosophy and Social Science Edition. 32 (6): 43–50. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ "The Origin of the Yellow Emperor Era Chronology" (PDF). 1 August 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ Cohen (2012), p. 1, 4.

- ^ a b c d e Aslaksen, Helmer (17 July 2010). "Mathematics of the Chinese calendar" (PDF). math.nus.edu.sg/aslaksen. Department of Maths, National University of Singapore. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2005.

- ^ "Alteplase/ramipril". Reactions Weekly. 1662 (1): 31. July 2017. doi:10.1007/s40278-017-33661-y. ISSN 0114-9954. S2CID 264005041.

- ^ "国家标准 | GB/T 33661-2017". Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ Xiao, Fang; Zhang, Juwen; Long, Bill (2017). "The Predicament, Revitalization, and Future of Traditional Chinese Festivals". Western Folklore. 76 (2): 181–196. JSTOR 44790971.

- ^ [Chapter 41: Five Elements]. [Guanzi] (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- ^ [Chapter 40: Four Sections]. [Guanzi] (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- ^ 中国农历发展简史 [A brief history of the development of Chinese Lunar calendar]. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Petersen, Jens Østergård (1992). "The Taiping Jing and the AD 102 Clepsydra Reform". Acta Orientalia. 53: 122–158. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986) [1954]. Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Vol. 3. pp. 109–110. Bibcode:1959scc3.book.....N.

- ^ Ho, Peng Yoke (2000). Li, Qi, and Shu: An Introduction to Science and Civilization in China. Mineola: Dover Publications. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-486-41445-4.

- ^ Restivo, Sal (1992). Mathematics in Society and History: Sociological Inquiries. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4020-0039-3.

- ^ Asiapac Editorial, ed. (2004). Origins of Chinese Science and Technology. Translated by Yang Liping; Y.N. Han. Singapore: Asiapac Books. p. 132. ISBN 978-981-229-376-3.

- ^ Sun Yat-sen (1982) [Telegram originally sent 1 January 1912]. 临时大总统改历改元通电 [Provisional President's open telegram on calendar change and era change]. 孙中山全集 [The Complete Works of Sun Yat-sen] (PDF). Vol. v. 2. Beijing: 中华书局. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ "Rules for the Chinese Calendar". ytliu0.github.io. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ CAS, Purple Mountain Observatory (1986). New Edition of Wànniánlì, revised edition. Popular Science Press.

- ^ Stone, Richard (2 November 2007). "Scientists Fete China's Supreme Polymath". Science. 318 (5851): 733. doi:10.1126/science.318.5851.733. PMID 17975042. S2CID 162156995.

- ^ "本世纪仅有4次!闰二月为何少见?-新华网". www.news.cn. Archived from the original on 2 May 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ Martzloff, Jean-Claude (1 September 2016). Astronomy and Calendars – The Other Chinese Mathematics: 104 BC - AD 1644. Springer. ISBN 978-3-662-49718-0. Archived from the original on 8 October 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ "The Chinese Sky". International Dunhuang Project. Archived from the original on 4 November 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ Sun, Xiaochun (1997). Helaine Selin (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 517. ISBN 0-7923-4066-3. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ Wenlin Dictionary: Picture of a fish tail.

- ^ Wenlin Dictionary: 己 may have depicted thread on a loom; an ancient meaning was 'unravel threads', which was later written 紀 jì. 己 was borrowed both for the word jǐ 'self', and for the name of the sixth Heavenly Stem (天干).

- ^ Wenlin Dictionary: "The seal has 𢆉 'knock against, offend' below, and 亠 above; the scholastic commentators say: to offend (亠 = ) 上 the superiors"

- ^ Wenlin Dictionary: 壬 rén depicts "a 丨 carrying pole supported 一 in the middle part and having one object attached at each end, as always done in China" —Karlgren (1923). (See 扁担 biǎndan). Now the character 任 rèn has the meaning of carrying a burden, and the original character 壬 is used only for the ninth of the ten heavenly stems (天干).

- ^ Wenlin Dictionary: 癶 "stretch out the legs" + 天; The nicely disposed grass, on which the Ancients poured the libations offered to the Manes

- ^ Sôma, Mitsuru; Kawabata, Kin-aki; Tanikawa, Kiyotaka (25 October 2004). "Units of Time in Ancient China and Japan". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan. 56 (5): 887–904. doi:10.1093/pasj/56.5.887.

- ^ 海上 (2005). Zhongguo ren de sui shi wen hua 中國人的歲時文化 [Timekeeping of the Chinese culture] (in Chinese). 岳麓書社. pp. 195. ISBN 978-7-80665-620-4.

- ^ a b 陳浩新. 「冷在三九,熱在三伏」 [Cold is in the Three Nines, heat is in the Three Fu]. Educational Resources – Hong Kong Observatory (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ "数九从哪一天开始到哪一天结束 数九寒冬中的数九从什么时候开始". 万年历. Archived from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ "Days of the week in Japanese". CJVLang. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Aslaksen, Helmer. "When is Chinese New Year?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2009. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ In the modern calendar where the solar terms are defined using astronomical calculation, it is possible to have only 11 complete months but with a month without a mid-climate, as in year 2033.

- ^ [Volume 6]. [New Book of Tang] (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

上元…。二年……,九月壬寅,大赦,去「乾元大圣光天文武孝感」号,去「上元」号,称元年,以十一月为岁首,月以斗所建辰为名。…。

元年建子月癸巳[2],…。己亥[9],…。丙午[16],…。己酉[29],…。庚戌[30],…。[初一壬午大雪,十七冬至]

建丑月辛亥[1],…。己未[9],…。乙亥[25],…。[初一辛亥,初三小寒,十八大寒]

宝应元年建寅月甲申[4],…。乙酉[5],…。丙戌[3],…。甲辰[24],…。戊申[28],…。[初一辛巳,初三立春,十八雨水]

建卯月辛亥[1],…。壬子[2],…。癸丑[3],…。乙丑[15],…。戊辰[18],…。庚午[20],…。壬申[22],…。[初一辛亥,初四惊蛰,十九春分]

建辰月壬午[3],…。甲午[5],…。戊申[19],…。[初一庚辰,初五清明,二十谷雨]

建巳月庚戌[1],…。壬子[3],…。甲寅[5],…。乙丑[16],…。大赦,改元年为宝应元年,复以正月为岁首,建巳月为四月。丙寅,…。[初一庚戌,初五甲寅立夏]。 - ^ a b Reingold, Edward M; Dershowitz, Nachum (2018). Calendrical Calculations (Ultimate ed.). Cambridge University press. ISBN 978-1-107-05762-3.

- ^ "Phenology". Merriam-Webster. 2020.

- ^ 孙蕾. "都说数九寒冬,可你知道"数九"怎么"数"?-新华网". m.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ "五九六九沿河看柳……"数九"知识你知道多少?-新华网". www.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 1 May 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ "2020 Buddhist Calendar". Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ "Mahayana Buddhist Vegetarian Observances". Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ 道教節日有哪些? [What are Some of the Holidays of Daoism?] (in Traditional Chinese). Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ 朱, 文鑫 (1934). 曆法通志 (in Chinese) (初版 ed.). Shanghai: 商務印書館. Archived from the original on 2 May 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ Kennedy, E. S. (1964). "The Chinese-Uighur Calendar as Described in the Islamic Sources". Isis. 55 (4): 435–443. doi:10.1086/349900. JSTOR 228314. S2CID 144085088.

Further reading

- Cohen, Alvin P. (2012). "Brief Note: The Origin of the Yellow Emperor Era Chronology". Asia Major. 25 (2): 1–13. JSTOR 43486143.

- Kai-Lung, Ho (2006). "The Political Power and the Mongolian Translation of the Chinese Calendar During the Yuan Dynasty". Central Asiatic Journal. 50 (1): 57–69. JSTOR 41928409.

External links

- Calendars

- Chinese months

- Gregorian-Lunar calendar years (1901–2100)

- Chinese calendar and holidays

- Chinese calendar with Auspicious Events

- Chinese Calendar Online

- Calendar conversion

- 2000-year Chinese-Western calendar converter From 1 CE to 2100 CE. Useful for historical studies. To use, put the western year 年 month 月day 日in the bottom row and click on 執行.

- Western-Chinese calendar converter

- Rules