Conquest of Majorca

| Conquest of Sa Pobla | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Reconquista | |||||||

Assault on Madina Mayurqa | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Catalan-Aragonese army 500 knights 15,000 peones Almogavars 25 ships 12 Galleys Catalan Navy 18 Taridas (a ship of burden) 100 vessels |

1,000 knights 18,000 Infantry[1] | ||||||

| History of Spain |

|---|

18th century map of Iberia |

| Timeline |

The conquest of the island of Majorca on behalf of the Roman Catholic kingdoms was carried out by King James I of Aragon between 1229 and 1231. The pact to carry out the invasion, concluded between James I and the ecclesiastical and secular leaders, was ratified in Tarragona on 28 August 1229. It was open and promised conditions of parity for all who wished to participate.[2]

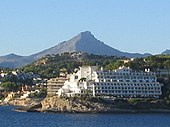

James I reached an agreement regarding the arrival of the Catholic troops with a local chief in the Port de Pollença, but the strong mistral winds forced the king to divert to the southern part of the island. He landed at midnight on 10 September 1229, on the coast where there is now the tourist resort of Santa Ponsa, the population centre of the Calviá municipality.[3] Although the city of Madina Mayurqa (now Palma de Mallorca) fell within the first year of the conquest, the Muslim resistance in the mountains lasted for three years.

After the conquest, James I divided the land among the nobles who accompanied him on the campaign, per the Llibre del Repartiment (Book of Distribution).[4] Later, he also conquered Ibiza, whose campaign ended in 1235, while Menorca had already surrendered to him in 1231.[5] While he occupied the island, James I created the Kingdom of Majorca, which became independent of the Crown of Aragon by the provisions of his will,[6] until its subsequent conquest by the Aragonese Pedro IV during the reign of James II of Majorca.

The first repopulation of Majorca consisted primarily of Catalan settlers, but a second wave, which took place towards the middle of the 13th century, also saw the arrival of Italians, Occitans, Aragonese, and Navarrese, due to a legal statute granting the settlers possession of the property seized during the conquest. Some Mudejar and Jewish residents remained in the area, with the Jewish residents receiving official status protecting their rights and granting them fiscal autonomy.[7]

Background

Majorca's geographical location was conducive to trade. The island had become a meeting point for traders from various Mediterranean coastal areas, including Perpignan, Maghreb, Genoa, Granada, Valencia and Catalonia. Eventually, a conglomerate was formed by Jewish, Roman Catholic, and Muslim merchants who transported and sold a variety of goods.[8]

Majorca was located in the boundary zone between Catholic and Muslim areas, at a nautical intersection close to Spain, southern France, Italy and North Africa.[9] The island served primarily as a trade interchange and transit point, and as a result the island's economy was inextricably linked with international trade traffic.[9] It developed an active market, monitored by the Consulate of the Sea.

In 707, the eldest son of Musa ibn Nusair, governor of the Umayyad caliphate in North Africa, landed on Majorca and plundered the island. In 903, the island was conquered by Issam al-Khawlani, ruler of the same caliphate, who took advantage of the destabilisation of the island population caused by a series of raids launched out of Normandy.[10][11] After this conquest, the city of Palma, then still partially under control by the Roman Empire, became part of the Emirate of Córdoba in al-Andalus. The last governor rebuilt it and named it Madina Mayurqa.[12][13] From then on, Majorca experienced substantial growth which led to the Muslim-controlled Balearic islands becoming a haven for Saracens pirates, besides serving as a base for the Berbers who used to attack Catholic ships in the western Mediterranean, hindering trade among Pisa, Genoa, Barcelona and Marseille.[14] The local economy was supported by a combination of stolen goods from raids on Catholic territories, naval trade, and taxes levied on Majorcan farmers.

Conquest of the island by Ramon Berenguer III

In 1114, the Count of Barcelona, Ramon Berenguer, gathered a group of nobles from Pisa and other Provençal and Italian cities, including the Viscount of Narbonne and the Count of Montpellier. This group of nobles launched a retaliatory expedition against the island to combat the pirate raids being organized on Majorca.[15][16] The objective of this mission was to wrest Majorca from Muslim control, establish a Roman Catholic government, and thereby prevent any further attacks on Catholic mercantile shipping by Muslim pirates.[15][16]

After an eight-month siege, Berenguer had to return home because an Almoravid offensive was threatening Barcelona. He left the Genoese in charge, but they ultimately gave up on the siege and fled with the captured spoils.[17][18][19] Although the siege failed, it laid the foundation for future Catalan naval power and strengthened strategic alliances among Catholic kingdoms around the Mediterranean.[20]

In Pisa there are still some remains that were moved from Mayurqa. There is also an account of the expedition in a Pisan document called Liber maiolichinus, in which Ramon Berenguer III is referred to by the appellate "Dux Catalensis" or "Catalanensis" and "catalanicus heros", while his subjects are called "Christicolas Catalanensis". This is considered the oldest documented reference to Catalonia that has been identified within the domains of the Count of Barcelona.[21]

The siege of Majorca prompted the Almoravid Emir to send a relative of his to take over the local government and rebuild the province. The new wāli led to a dynasty, the Banû Gâniya,[22] which, from its capital at Madina Mayurqa, tried to reconquer the Almoravid empire.[23] King Alfonso II, using Sicilian ships, organised a new expedition and again attempted to conquer the island, but was unsuccessful.[24]

Almoravid and Almohad Empire

After the Count of Barcelona withdrew his troops, Majorca returned to uncontested Muslim control under the Almoravid family, Banû Gâniya. As a result of the Almohad reunification, he created a new independent state in the Balearic Islands.[19] Trade between the various Mediterranean enclaves continued despite ongoing attacks on commercial shipping by Muslim forces. In 1148, Muhammad ben Gâniya signed a treaty of non-aggression in Genoa and Pisa, which was revalidated in 1177 and in subsequent years.[19] The wāli was one of the sons of the Almoravid sultan, Ali ibn Yusuf, which meant that his kingdom had dynastic legitimacy. He proclaimed its independence in 1146.[25][26]

When Gâniya acceded to the Majorcan seat, there were temples, inns, and sanitary conveniences that had been built by the previous wāli, al-Khawlani. There were social meeting places and amenities as well as three enclosures and some 48 mosques spread across the island.[27] There were also hydraulic and wind mills which were used to grind flour and extract groundwater.[28] Majorcan production was based on irrigated and rainfed products – oil, salt, mules and firewood, all of which were particularly useful to the military regime of the time.[27]

During this period, the Majorcans developed irrigation agriculture and constructed water sources, ditches, and channels. The land was divided into farmsteads and operated by family clans in collectives. Management and administrative functions were concentrated in Medina Mayurqa. Cultural and artistic life thrived, and the city soon became a trade centre between the East and West.[10]

Although the Almoravids preached a more orthodox compliance to Islam in Barbary, Majorca was influenced by Andalusian culture, which meant their religious precepts were less strict. Pressure from King Alfonso I and the emerging Almohad power led to a crisis in the Almoravid administration and, after the fall of Marrakech in 1147, it eventually succumbed to this new empire.[29]

In 1203, an Almohad fleet that was leaving Denia fought a fierce battle against Gâniya,[30] the last Almoravid stronghold of the Andalus period, incorporating Majorca into their domain. It was then ruled by different wālis who were appointed from Marrakech, until when Abu Yahya was appointed as its governor in 1208.[23] He created a semi-independent principality with only a formal submission to the Almohad emir.

Status of the Crown of Aragon

Having pacified their territories and having normalized economic recovery following the drought that began in 1212, the Crown of Aragon began to develop an expansionary policy.[31] Also in 1212, the Muslims were defeated at the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, an event that resulted in subsequent Almohad decline and allowed the Aragonese kingdom to reassert its power.[32] A northward expansion was halted at the Battle of Muret, where the father of James I, Peter II of Aragon, was killed in combat. The kingdom then turned southward, seeing the benefits of having greater control of the Mediterranean.[33][34] By then, James I was only five years old and, after a series of events, he was interned in the Templar castle of Monzón, in the province of Huesca, under the tutelage of Simon de Montfort,[35] where he received an education in a religious and military environment.[36]

Preparations

James I's motivation to conquer Valencia and the Balearic Islands was driven by a combination of economic and strategic factors. Valencia was a rich land that could be used to provide new territory for the population of the Kingdom of Aragon, and Catalonia offered new fiefdoms for the nobility. The king of Castile, Ferdinand III, had tried to take parts of Valencia that were, in principle, reserved for the king of Aragon. Meanwhile, a conquest of the Balearic Islands enabled Catalan and Provence merchants to eliminate competition from Majorcan merchants and also dismantle the Barbary pirates who used Majorca as a safe haven.[37] The taking of the Balearic Islands represented not only a retaliatory strike for the damage caused to the merchants, but also the beginning of a planned expansion to obtain a trade monopoly with Syria and Alexandria, thereby enhancing trade with Italy and the rest of the Mediterranean. It was after the success achieved in Majorca that James I decided that he was ready to conquer the kingdom of Valencia, which capitulated after the Battle of Puig in 1237.[38]

Catalan Courts Assembly

The Catalan Courts, an advisory council that met in December 1228 in Barcelona, discussed the desirability of carrying out a military campaign against the Balearic Islands or Valencia. The three estates took part in this assembly, in which the king guaranteed the Bishop of Barcelona the concessions from the churches on the islands.[40]

During this period, there was a group of families of the upper bourgeoisie who formed the minority leadership of the city.[41] These families had acquired their power and wealth at the end of the previous century and were also the leaders of the city government. Their economic interests were connected to any future conquests of the monarch. In order to increase the profitability of their investments, they demanded more and more stringency towards their nobility or proprietary rights.

Father Grony, the representative of the city of Barcelona, offered the king assistance from the city for this expedition.[41] After that first assembly, there were others, until finally, the king had chosen the option of Majorca.

The attack on Majorcan lands was already supported by tradesmen and businessmen, so only the support of the nobles was pending; their support was essential in carrying out the expedition. According to James I, it was the expert Catalan navigator Pedro Martell who encouraged him to embark on that enterprise during a dinner banquet that the latter held in Tarragona in late 1228.[42][43]

Both the political and religious agenda of the enterprise were clearly defined in the discourses of the courts. James I opened his speech by uttering a verse in Latin, whose origin is not clear but which was often used in medieval times to seek divine inspiration for the rest of the sermon: "Illumina cor meum, Domine, et verba mea de Spiritu Sancto" (Enlighten my heart, O Lord, and my words by the Holy Spirit). James I suggested that the expedition would be a "good work".[44] The church and the influence of religion in the reign of James I is manifold, his life and work reflecting the importance of Raymond of Penyafort, the Dominicans and Peter Nolasco, and the founding of the order of Mercy.[45]

According to the philologist Rafael Alarcon Herrera, the spiritual values of the Templars played a key role in the conquest. In 1129 the order had already included the Balearics in its list of territories to conquer a year before their recognition in the Council of Troyes. Thus, during the dinner, they apparently alluded to the monarch that the invasion was "God's will", a fact which may have encouraged the young king, given the connection of that house[46] to his birth and education. In fact, much of the conquest was planned and executed by the Templars, proof of which is in the gift of the castle, the Jewish district, more than a third of the city and an exclusive port given to the order[47] after the conquest. Possibly, the Templars provided James I with the best troops of those that took part in the conquest.[48]

Financing and support from the nobility

It is possible that, though the purpose of the dinner was to determine the necessary investments for the venture, the attack on the island was already decided. At that meeting, the Catalan nobles declared their support and offered economic and military aid to the king, each pledging a number of knights and foot soldiers.[43] The collection of the bovaje tax, a tax on yokes of oxen paid to the king and used to fund military ventures, was also negotiated, as well as the signing of a peace treaty and a truce throughout the Catalonia region.[49][50] In return, they would receive a share of the conquered lands proportional to the support given to the conquest; the king promised to appoint arbitrators for the distribution of lands and loot.[51] The men who were appointed to lead the conquest were the Master of the Knights Templar, Bishop Berenguer de Palou of Barcelona, Bishop of Girona, Count Nuño Sánchez del Roussillon (who, after the king, was the most important figure in the venture),[52] Count Hugh IV of Ampurias,[53] Catalan knights Ramón Alamán and Ramón Berenguer de Ager, and the wealthy gentlemen of Aragon, Jimeno de Urrea and Pedro Cornel.

The king also requested a loan of 60,000 Aragonese pounds from the merchants, promising that it would be returned when the city of Majorca was taken, although it is unknown if they were given in gold or silver.[54] Concerning assistance that the citizens of his kingdom could contribute towards the campaign, he remarked that he could not give them anything in return, since he had nothing, but that on achieving victory he would turn over property covering the entire length of sea from the beaches of Barcelona up to the beaches of Majorca. Consequently, in modern times, when the boundaries of a Catalan beachfront property are discussed, the owner technically controls the section of the sea from the shore of their property all the way to the opposite stretch of shore on Majorca.[55]

Participants

In the first meeting of the court, the operation was presented only for subjects of the Crown, but when the venture began to be considered as a crusade and to fall within a papal bull, it was open to all who wished to participate. Thus, private groups and Jews began to join.[56] The Jews were called Xuetes and their importance was partly qualitative as they represented the industrial, commercial and scientific activity of the Crown.[57][58] From his perspective, James I considered this set preferable to Christians from the nobility, who could become political rivals, so he focused on persuading this group of citizens to move their homes to new conquered territories, which served as a cornerstone for his policies as they were subjects whose contribution to the economy and the colonisation of the island would be substantial.[59]

The king's sympathy for the Jewish collective came from an early age. From when he was recognised as king in 1214, he had a Jewish doctor named Açac Abenvenist at his disposal. Besides taking care of his health, this doctor was once commissioned to obtain a temporary truce with the Muslims.[60]

The nobles and bishops who contributed goods and troops to the formation of the army included some nobles from the royal family, such as Nuño Sánchez himself, Ramón Berenguer IV's grandson, who took 100 knights. There was also Count Hugh IV of Ampurias who contributed 60 along with his son Ponce Hugo.[61] Among the nobles there was also the most important magnate in Catalonia, Guillem Ramón de Montcada who brought 400 knights along with his nephew.[62] The members of the clergy also provided men, allocating 100 men to each company.[63] The Archbishop of Tarragona, Aspàreg de la Barca, and Ferrer de Pallarés, prelate of Tarragona (who later became bishop of Valencia), also took part, providing a galley and four knights, and became part of the king's War Council.[64]

It was not only the nobles and prelates who were committed to the venture, but also free men and cities, and Catalans were not the only ones who provided ships and financial support to the cause.[n. 1] Barcelona, which along with Tortosa and Tarragona had been the most affected by piracy, had a major role in the meetings of the Court, as demonstrated by the involvement of a significant number of its citizens. Berenguer Gerard and Pedro Grony were directly involved in the talks and Berenguer Durfort, a member of a powerful merchant family, was appointed the first mayor of the City of Majorca after the conquest.[65] The venture was presented as a crusade against the infidels, like that undertaken against Peñíscola following other courts held in Tortosa in 1225. King James took the cross in Lleida in April 1229.[n. 2]

Although the conquest was primarily initiated by the Catalans, there was collaboration with many other cities and towns in Provence – Montpellier, Marseilles, and Narbonne, or Italian cities such as Genoa.[66][67] The cities of Tortosa, Tarragona, and Barcelona, the most affected by the pillaging of pirates, were the ones who offered the most ships. Ramón de Plegamans, a wealthy businessman in the royal service, was in charge of preparing the fleet,[n. 3] but later did not participate in the campaign.

Although the lower class within the Aragonese cities declined to collaborate, in a meeting held in Lleida a few days after the Barcelona Courts, James I was able to get a number of Aragonese nobles to take part because of their vassalage links with the king. The Lleidans ultimately supported the venture, though at first it appeared that they would not participate, because like the Aragonese they were more interested in Valencia, a fact that James I subsequently took advantage of when preparing for the conquest of that Muslim kingdom.[51][68] Finally, among the knights who embarked on the expedition, about 200 came from Aragon, of which 150 were provided by Pedro Cornel and 30 by Pedro de Lizana,[n. 4] the king's chamberlain who was eventually appointed governor general of the island.[69] Some of the Aragonese nobles who got involved had been part of the monarch's advisory board.[70] Although they all followed the monarch in the conquest of Valencia, many of his mesnaderos settled on the island in order to receive benefits in the division of spoils, further promoting the repopulation of Aragon leading to extensive economic and social activity.[71]

Papal bull and final preparations

Preparations for the venture intensified. Holding the papal bull that Pope Urban II had granted to James I's grandfather, Peter I of Aragon, in 1095, Pope Gregory IX dispatched two documents on 13 February 1229, in which he reaffirmed his power to grant pardons in Aragon to those men who would organise themselves into military groups against the Muslims. He also reminded the coastal towns of Genoa, Pisa and Marseille that a trade veto had been imposed on military materials for the Majorcans.[19]: 17 [72]

In August 1229, the archbishop of Tarragona donated 600 cuarteras[n. 5] of barley, and one day later, the king reaffirmed the promises of granting land. He also instituted prosecutors and received oaths from several knights.[19]

The rejection of the Aragonese caused "the Conqueror" great annoyance but, upon arrival in Barcelona, he was pleased that a powerful navy had been prepared. In addition to about 100 small boats, there were 25 warships, 12 galleys and 18 táridas to transport horses and siege engines.[73][74]

Although the Catalan armed naval fleet had existed since the ninth century, even before the Castillian, it was James I who, during his reign, led it to demonstrate its true power.[75]

On the day of Our Lady of August, all the barons and knights of Catalonia, along with the king, travelled to Tarragona and Salou, carrying all their equipment – guns, sails, rigging, ships and táridas which were loaded with logs, flour, barley, meat, cheese, wine, water and 'biscuit', a type of bread that was re-toasted to harden and preserve it. Before leaving, the king, along with the nobles and his entourage, attended a Mass given by Berenguer de Palou in the Tarragona Cathedral where he also took communion, while the army took communion in a chapel that had been built at the port for that purpose.[76]

Most citizens of Tarragona came to witness the spectacle of the fleet's departure, gathering along the rocky cliffs rising above the sea. The ship on which Guillem de Montcada travelled was led by Nicholas Bonet and was ordered to be at the forefront, with captain Carroz to the rear, while the galleys were arranged in a circle surrounding the transport ships to safeguard them.[76] The last ship to set sail was a galley from Montpellier which had originally been intended for the king and his knights, but at the last moment, a multitude of volunteers appeared and had to be boarded on the ship.[76]

Armies

Christian army

A very rough estimate of the Christian army, composed of aristocratic armies, would give the figure of 1,500 knights and 15,000 footmen, divided among the following:

- Army of the House of Aragon, 150/200 knights.

- Army of Nuño Sánchez I of Roussillon and Cerdagne,[77] 100 knights.[35]

- Army of Guillem II de Bearn i Montcada,[77] 100 knights.[35]

- Army of Ramón Alemany de Cervelló í de Querol, 30 knights.

- Army of Hug V de Mataplana,[78] 50 knights.[35]

- Army of Berenguer de Palou II, 99 knights.

- Army of Guillem Aycard and Balduino Gemberto, 600 knights and several ships.[19]: 20

- Army of Hug IV of Empúries,[77] 50 knights.[35]

- Army of the bishop of Girona, Guillem de Montgrí,[79][80] 100 knights.

- Army of the Abbot of Sant Feliu de Guíxols, Bernat Descoll.

- Army of the provost of the archbishop of Tarragona, Espárago de la Barca [es],[81] 100 knights and 1,000 lancers.

- Army of the Knights Templar.

- Army of the Knights of Malta.

- Army of Guillem I de Cervelló, 100 knights.[35]

- Army of Ferrer de San Martín,[82] 100 knights.[35]

- Army of Ramón II de Montcada, 25/50 knights.[83]

- Army of Ramon Berenguer de Áger, 50 knights.[35][81]

- Army of Galçeran de Pinós, 50 knights.[35]

- Army of Bernat de Santa Eugènia,[77] 30 knights.

- Army of Guillem de Claramunt, 30 knights.[35]

- Army of Raimundo Alamán, 30 knights.[35]

- Army of Pedro Cornel, 150 soldiers.[35]

- Army of Gilabert de Cruilles, 30 knights.[35]

Muslim army

According to various accounts, the Muslim king of the island, Abu Yahya, had between 18,000 and 42,000 men, and between 2,000 and 5,000 horses.[84]

The weaponry of the Muslims did not differ much from those of the Christians – meshes, spears, mallets, arrows and leather shields resistant to swords. As evidenced from a display at the Museum of Catalan Art, one of the widely used Muslim weapons from the battlements was the Fustibalus, similar to a slingshot contraption, whose bands were tied to a wooden stick.[85][86] The Muslims also had catapults and low shot machines, called algarradas by James I, which were very light, rapid, and capable of destroying several enemy tents at once.[87]

Conquest

Journey and landing of the troops

The expedition left for Majorca from Salou, Cambrils and Tarragona on 5 September 1229, with a fleet of over 150 vessels, the majority of which were Catalan.[88] Various sources indicate an armed contingent of between 800 and 1,500 men and 15,000 soldiers.[88][89] The Muslim king of the island, Abu Yahya, had between 18,000 and 42,000 men and between 2,000 and 5,000 horses[84] (according to various reports) and received no military support, neither from the peninsula, nor from North Africa, by which they tried to hinder the Christian advance towards the capital as much as possible.

Some of the Christian ships were built at the expense of the Crown, but most of them were private contributions.[90] Because of his experience and knowledge of the Balearics, Peter Martell was appointed head of the fleet, while Guillem de Montcada, who previously had asked the king to allow him to take charge of the mission because of the risk that the enterprise entailed, served as lieutenant, all under the command of James I, who due to his enthusiasm did not allow impositions and rejected the petition.[90] The royal vessel, heading the fleet, was skippered by Nicholas Bonet, followed by the vessels of Bearne, Martell and Carroz in that order.[90]

The journey to the island was hampered by a severe storm that nearly caused the convoy to retreat. After three days, between Friday September 7 and part of Saturday, the entire Christian fleet arrived at Pantaleu island,[91] located on the coast of the present-day town of San Telmo, a hamlet belonging to the municipality of present-day Andrach. James I's forces were not bothered by the possible threat of early conflict with the Muslim fleet, but the storm was so harsh that in the midst of the tempest the king swore to Santa Maria that he would build a cathedral to venerate her if their lives were spared.[92] Local tradition has it that the first royal mass was held on this island and that a water trough where the king watered his horse was kept there, but in 1868 it was destroyed by revolutionaries who wanted to eliminate the vestiges of the former feudal system.[93]

While the Christians were preparing to begin the assault, Abu Yahya had to suppress a revolt that had been caused by his uncle, Abu Has Ibn Sayri, and as a reprimand was preparing to execute 50 of the rioters, but the governor pardoned them so they could help in the defence work. However, once pardoned they left Medina Mayurqa for their homes; some of them preferred to side with the Christians, as was the case of Ali of La Palomera or by Ben Abed, a Muslim who provided supplies to James I for three months.[84]

Battle of Portopí

The battle of Portopí was the main armed conflict in open terrain between the Christian troops of James I and the Muslim troops of Abu Yahya in the conquest. It took place on September 12 at various points on the Na Bourgeois mountains (formerly called Portopí highlands), about halfway between Santa Ponsa and the City of Majorca, an area known locally as the "Coll de sa Batalla".[94] Though the Christians were victorious, they suffered significant casualties, including Guillem II de Bearne and his nephew Ramón, whose relation to each other had previously given as brothers, so they were usually referred to as "the Montcada brothers".[95]

Before the start of the skirmish, the Muslim army had been deployed throughout the Portopí highlands, knowing that the Christians would have to cross these mountains on their way to Medina Mayurqa. On the other hand, hours before the confrontation and aware of the danger that threatened them, Guillem de Montcada and Nuño Sánchez debated who would lead the vanguard of troops; in the end it was Montcada. However, they penetrated the Muslim defense awkwardly, falling into an ambush that left them completely surrounded, until they were killed.[96] James I, who was unaware at the time of their deaths, followed the same route, advancing with the rest of the army, intending to join them and participate in the fray with them, until he came upon the enemy in the mountains. The Montcadas' bodies were found disfigured by multiple injuries and they were interred in rich caskets at the Santes Creus monastery in the present municipality of Aiguamúrcia, in the province of Tarragona.[97]

According to the chronicles of the historian Desclot Bernat, the Christian forces left much to be desired, as there were several times when the king had to insist that his men enter the battle, even admonishing them on two occasions when he exclaimed the phrase that later passed down into Majorcan folk history: "For shame knights, shame."[98][99] Finally, the military superiority of the Christians caused the Muslims to withdraw. When James I's knights requested a pause to pay tribute to the nobles who had died, the Muslims were left to flee to the medina where they took refuge. Desclot says in his article that only fourteen men were killed, probably relatives of the Montcadas, among them Hug Desfar and Hug de Mataplana, but only a few commoners died.[100]

At night, James I's army stopped to rest in the present town of Bendinat. The popular tradition has it that after dinner the king uttered the words in Catalan "bé hem dinat" ("We have eaten well") which could have given that location the name.[101] The news of the death of the Montcadas was given to James I by Berenguer de Palou and two days later, on September 14, they were sent to bury his remains amidst scenes of grief and sadness.

Siege of Medina Mayurqa and the pacification of the island

Grief over the loss of the Montcadas and the decision over the next location of the camp kept the king and his troops busy for the next eight days. From there, they moved and camped north of the city, between the wall and the area known today as "La Real". James I ordered two trebuchets, a catapult and a Turkish mangonel to be mounted, with which they subsequently began to bomb the city.[12] The actual site of the camp was strategically chosen based on its proximity to the canal that supplied water to the city, but also for its distance from the springs and Muslim mangonels. James I bore in mind what happened to his father in Muret and, sensing that the siege was to extend longer than anticipated, ordered the construction of a fence around the camp that would ensure the safety of his troops.[102]

While the Christian army camped outside the Medina, they received a visit from a wealthy and well-regarded Muslim named Ben Abed who appeared before the king and told him that he was in command of 800 Muslim villages in the mountains and wanted to offer all kinds of help and hostages, provided the king maintain peace with him. Along with advice on the practices of the besieged, this alliance represented powerful help to the Christians. As a first test of submission, Abed gave James I twenty horses laden with oats, and goats and chickens, while the king gave him one of his banners, so that his messengers could appear before the Christian hosts without being attacked.[76]

The response from the besieged was immediate and they answered with fourteen algarradas and two trebuchets. Faced with the unstoppable advance of the king's troops, the Moors tied several Christian prisoners completely naked on top of the walls to prevent it from being bombed. However, the prisoners instead screamed exhortations to their compatriots to continue firing.[103] James I, hearing the pleas in which they said that their death would bring them glory, commended them to God and redoubled the discharges. Despite the discharges going over their heads, this caused the Muslims to return the prisoners to their cell, seeing that their blackmail was unsuccessful.[103] In response to the Muslim ploy, James I catapulted the 400 heads of soldiers who had been captured in a skirmish (commanded by Lieutenant Vali, Fati Allah) while trying to reopen the water supply to Medina Mayurqa that the Christians had previously blocked.[104]

Knowing they were losing, the Muslims offered various negotiations to discuss the surrender of Abu Yahya. James I, in order to minimize losses, save lives and keep the city intact, was in favour of reaching an agreement, but the relatives of the Montcadas and the bishop of Barcelona demanded revenge and extermination.[105] Abu Yahya then withdrew from negotiations as the king was not accepting the conditions. The Wali assured that from then on every Saracen would be worth twice as much.[16] The king was left with no choice but to yield to the desires of his allies and continue with the campaign that culminated in the taking of Palma de Mallorca.

Taking of Medina Mayurqa

The strategy used to conduct a siege on a walled city usually involved encircling the city and waiting for its defenders to suffer from thirst and starvation. Due to the weather conditions on the island during that time of year and the low morale and energy of his troops, the king elected to break down the walls and assault the towers in order to end the venture as soon as possible. Among the various machines that were usually used at the time were wooden siege towers, woven wattles, battering rams, lath crossbows and trebuchets.[86]

After heavy fighting that lasted for months during the siege, the Christians began making inroads, knocking down walls and defence towers.[106] The siege was so difficult that when the Christians opened a gap on one of the walls, the Muslims erected another wall made of stone and lime to cover it.[107]

One of the main strategies of the Christian attack was to use mines to destabilize the walls, but the Muslims countered with countermines.[106] Finally, on 31 December 1229, James I managed to take Medina Mayurqa.[106][108] The initial moment occurred when a gang of six soldiers managed to place a banner on top of one of the towers of the city and began to signal to the rest of the army to follow, while shouting, "In, in, everything is ours!"[109] The soldier who went ahead of the rest of the troops, waving the banner of the Crown of Aragon on that tower and encouraging the other five to follow was Arnaldo Sorell, and was subsequently knighted by James I in return for his courage.[110] The rest of the Christian army entered the city shouting, "Santa Maria, Santa Maria," an act that was typical of medieval times.

Pedro Marsilio indicates that 50 men launched their horses against the Saracens in the name of God, while shouting aloud, "Help us Holy Mary, Mother of Our Lord," and again, "For shame, knights, shame," while their horses butted forward and stirred-up the Saracens who had remained in the city, while thousands of others fled through the back gates.[111]

James' triumphal entry occurred through the main gate of the city, called in Arabic "Bab al-Kofol" or "Bab al-Kahl", and locally "Porta de la Conquesta", the "Porta de Santa Margalida", the "Porta de Esvaïdor", or "Porta Graffiti".[112] A commemorative plate was retained from this gate after it was demolished in 1912, years after the wall itself had been destroyed.[112] In the Diocesan Museum of Majorca, there is a medieval picture with a fight scene in the altarpiece of San Jorge developed by the Flemish painter, Peter Nisart.[112]

It is said that, after taking the city, the Christians apprehended Abu Yahya and tortured him for a month and a half to make him confess where the pirates kept their treasure. They even cut the throat of his 16-year-old son in his presence, while his other son was converted to Christianity to save himself. Abu Yahya was tortured to death before he would reveal where the treasure was stored.[113] At the same time, they burned the city and slaughtered the people who had failed to escape through the north door and had been left behind in the houses, although a few converted to Christianity to save themselves.[114] The slaughter was so widespread that the resulting thousands of corpses could not be buried; as a result, the Christian troops were soon depleted by a plague epidemic due to the putrefaction of the bodies.[115]

According to the Chronicles of James I, though it appears to be literary information according to the epic atmosphere of the campaign, 20,000 Muslims were killed, while another 30,000 left the city without being noticed. On the other hand, in the Tramuntana Mountains and in the region of Artà, they had managed to shelter some 20,000 people including civilians and armed men, but were ultimately captured by the Christians.[116]

Dispute over the division of the spoils

As soon as they entered the city, the conquerors began to take over what they saw, and soon discord began to emerge among the troops.[117] To avoid conflict here, the king suggested first dealing with the Moors who had fled to the mountains, to avoid a possible counter-attack, but their desire to seize the goods of the vanquished prompted the Bishop of Barcelona and Nuño Sánchez to propose that a public auction be held.[117] The spoils collected during the early days were abundant, with each taking what they wished. When it was revealed that they had to pay, they revolted, which ended in them storming the house where the captain of Tarragona had been installed.[117] In response, James I ordered that they bring everything they had gotten to the castle where the Templars were settled. He then said to the people that the distribution would be fair, and that if they continued looting homes they would be hanged.[117] The sacking of the city lasted until 30 April 1230, a month before the master of the house of San Juan had arrived on the island with some of his knights. He requested that, in addition to land, they be given one building and some property.[118] James gave in to their demands and gave them the deracenal house, plus four galleys that the wali had captured from the island.[118] Another of the problems that James I faced was the abandonment of the city by the troops once the military targets were achieved. Thus he sent Pedro Cornel to Barcelona to recruit 150 knights to finish conquering the rest of the island.[119]

Muslim resistance

As a result of internal disputes among the conquerors over the distribution of the spoils, the Muslims who escaped were able to organise in the northern mountains of Majorca and last for two years, until mid-1232, when the complete conquest of the territory was accomplished. However, the majority of the Muslim population did not offer much resistance and remained disunited, facilitating the invasion.[120]

To combat pockets of resistance that had been organised in the mountains, several cavalcades were organised. The first one, led by James I, failed because the troops had little strength and were plagued with illness.[7] The second raid took place in March, against the Muslims who had been hiding in the Tramuntana Mountains. A group of rebels were found there and they surrendered on condition that they agreed not to receive assistance from other Moorish groups who were in the mountains.[7] While the Christians fulfilled the agreement, they took the opportunity to look for new arrivals. A detachment under the command of Pedro Maza found a cave where a large number of Muslims had hidden; the Muslims eventually surrendered.[7]

James I, having solved the major problems and eager to return home, decided to go back to Barcelona, naming Berenguer de Santa Eugenia as his lieutenant. Berenguer de Santa Eugenia later became governor of the island and was in charge of halting the Muslim resistance in the castles and mountains of Majorca.[121]

James I's return trip to Catalonia was carried out in the galley of the Occitan knight, Ramón Canet,[122] on 28 October 1230, arriving three days later in Barcelona to a reception with many festivities, as news of his victory had preceded him and his vassals wanted to extol him as the greatest monarch of the century.[121] However, shortly afterwards, it was rumoured that a large Muslim squadron was forming in Tunisia to fight back and wrest control of the island. Thus, he returned to Majorca and managed to take the castles where part of the Muslim resistance was found: the castles of Pollensa, Santueri in Felanich, and the Alaró in the town of the same name.[121] The last stronghold of the Saracen forces was in Pollensa, within what is known as the castle of the King, located on a hill 492 metres above sea level.[123] Once he had taken these fortresses and was convinced that no army would come from Africa to confront him, he again returned to Catalonia.[121]

During the period from 31 December 1229 to 30 October 1230, the towns located in the Pla, Migjorn, Llevant and the northeast of the island were taken. Finally, those who did not manage to flee to North Africa or to Menorca were reduced and turned into slaves, although a few managed to remain on their land.

The last pocket of resistance caused James I to again return to the island in May 1232, when about 2,000 Saracens, who had taken shelter in the mountains, refused to surrender or yield to anyone aside from James I himself.[121]

Muslim perspective

One of Majorca's leading historians and archaeologists, Guillermo Rosselló Bordoy, worked alongside philologist Nicolau Roser Nebot in the translation of the first known Muslim account of the conquest of Majorca, Kitab ta'rih Mayurqa, discovered by Professor Muhammad Ben Ma'mar.[124] The work, which was discovered in the late sixteenth century but was believed lost,[125] was found on a CD in a library in Tindouf when, under the auspices of a patron, they were performing worldwide cataloguing and digitisation work on Arab documents.[126] This contribution is the first time that details of the conquest became known from the point of view of the conquered.

Its author was Ibn Amira Al-Mahzumi, an Andalusian born in Alzira in 1184 who fled to Africa during the war and who is believed to have died in Tunisia between 1251 and 1259.[127] His account is considered to be of important historical and literary value, since it is the only document that recounts the vision of the campaign on the part of the conquered.[127] In its 26 pages it describes previously unknown details, such as the name of the landing site, Sanat Busa, which in Arabic means "place of reeds".[127]

Ma'mar Ben Muhammad, professor of the University of Oran, carried out the first transcription and annotation,[128] and subsequently Guillermo Rosselló Bordoy translated it into Catalan in 2009. Since its introduction, it rapidly became a small best seller in the Balearics.[129]

Among other information, it confirms the presence of 50 ships in the Christian fleet as well as its detour through the Tramuntana coast, as it was spotted from coastal watchtowers by scouts who informed Abu Yahya. The Muslim & Christian accounts of the treatment given to the Muslim governor of Majorca do not agree with each other; based on the Muslim account, it seems that he was assassinated with his family without fulfilling the promises made in the capitulation treaty as the Christian accounts maintain. The Muslim account concurs with other details such as the capture of the Christian ships in Ibiza as an excuse for the invasion, the landing site, the Battle of Portopí and 24,000 Muslim casualties.[130]

Distribution of land and property

At the time of the invasion, Majorca had 816 farms.[63] The distribution of land and property on the island was complete and was performed as previously agreed in Parliament and according to what was available in the Llibre del Repartiment.[131] King James I divided the island into eight sections, making one half the "medietas regis" and the other half the "medietas magnatis";[132] that is, half of the island passed into the hands of the king and the other half to the participating nobles or arbitrators of the distribution. Information exists only on the properties and lands composing the "medietas regis", which were what appeared in the Llibre del Repartiment, but it is believed that the "medietas magnatis" was similar.[n. 6] The groups that had the greatest participation in the enterprise were Barcelona and Marseille, the first with a total of 877 horses and the second with 636, followed by the house of the Templars which had 525.[133][134]

The nucleus of the island feudal system which James I installed consisted of jurisdictional units that were subject to the provision of a number of armed defenders called chivalry, although some of them, because of their relevance, seniority or importance to the successful bidding lord, came to be called baronies.[135] The knights had a number of privileges that made them figures honoured by the king, mainly due to the nobility of their lineage and their kindness.[136] Some of their rights and customs included that they did not sit down to eat with their armour bearer, but instead with some other honourable knights or gentlemen who deserved this privilege.[136] However, the legal system allowed the cavalries to be leased or sold to third parties, even though they were knights, a fact which in return gave them lesser civil and criminal jurisdiction, permission to collect certain manorial rights or establish a clergy.[135]

Medieta regis and magnatis

The medietas regis comprised about 2113 houses, about 320 urban workshops and 47,000 hectares divided into 817 estates.[137] In turn the monarch divided this part among the military orders that supported the conquest, mainly the Knights Templar, the infants, officers and the men in their charge and the free men and the cities and towns. Thus, the Order of the Knights Templars received 22,000 hectares, 393 houses, 54 shops and 525 horses. The men in the service of the monarch[n. 7] got 65,000 hectares. The cities[n. 8] received 50,000 hectares and the infant Alfonso, his first-born, got 14,500 hectares.

The medietas magnatum were partitioned among the four main participants, which in turn were to distribute the land among their men, freemen and religious communities. The four participants were Guillem Montcada, viscount of Bearn,[n. 9] Hug of Empúries, Nuño Sánchez and the Bishop of Barcelona.

Origin of the conquerors

The conquerors came from various locations and in different proportions, and so some of the current names of the towns are those of their masters, such as the village of Deya, named for the conqueror who was probably Nuño Sánchez's main knight since this class of settlers was given the villas and castles.[110] Similarly, other names were given, such as Estellenchs by the Estella and Santa Eugenia gentlemen, from Bernardo de Santa Eugenia.[110] Thus, according to the Llibre dels Repartiment, the conquered lands were divided among people from Catalonia (39.71%), Occitania (24.26%), Italy (16.19%), Aragon (7.35%), Navarra (5.88%), France (4.42%), Castille (1.47%) and Flanders (0.73%).[66] Due to the extermination or expulsion of most of the native population, there was not enough manpower to cultivate the fields, so the island's first franchise letters were issued in 1230 and offered privileges which attracted more settlers for the purpose of cultivation.[138] The new Majorcan population came mainly from Catalonia, more specifically from the northeast and east, from Ampurdán, although there did remain a small Moorish population. As a result, the language of Majorca is an eastern Catalan dialect (which was already used in the texts of the Royal Chancellery by the Crown of Aragon, whose scribes included Bernat Metge, one of the most important figures of Catalan literature)[138] derived in turn from Limousin and called Majorquin.[139]

Many typical Majorcan surnames, as they came into hereditary use throughout the various strata of the island in the thirteenth century, refer to the original lands of the first repopulators.[140] Some examples are Català (Catalan), Pisa (Pisa), Cerdà (from Cerdagne), Vallespir, Rossello (Roussillon), Corró (the population of Valle Franquesas), or Balaguer and Cervera (towns in the province of Lleida).

The toponymic picture of the island after 1232 was composed of various elements, such as anthroponyms, denominatives, phytonyms and geographic names, but the origin of many others are still unclear because of the permeability to all kinds of influences linked to the Balearic Islands from antiquity.[141]

It seems that, before the conquest, the Christian population on the island was low or even non-existent. A mosque, known today as the Sant Miquel church, had to be converted in order to hold the first mass after the taking of the city. This suggests that Christian worship and priesthood were non-existent before then.[142] Majorcan historians say that during the long period of Muslim captivity, religion and the Catholic faith were never completely extinguished, given that the Santa Eulàlia Cathedral, whose original construction predates the Saracen invasion, never served as a mosque, although it is unclear whether the troops of James I found any Mozarabic Christians.[143]

Menorca and Ibiza

After the island was captured and annexed to the Crown of Aragon, James I dismissed an attack on Menorca because of the casualties suffered during the conquest of Majorca and because the troops were needed for the conquest of Valencia. At this point, they conceived of a strategy that would allow them to still gain Menorca. Ramón de Serra, acting commander of the Knights Templar,[144] advised the king to send a committee to the neighbouring island to attempt to obtain a Muslim surrender. The king decided that the Master Templar, Bernardo de Santa Eugénia, and Knight Templar, Pedro Masa, would accompany him, each with their respective ships.[145] While the delegation started the discussions with the Muslim neighbours, in the place where the Castle of Capdepera now stands, James I ordered the building of large fires that could be clearly seen from Menorca as a way to make the Moors from the neighbouring island believe that there was a great army encamped there ready to invade. This act had its desired effect, causing the recapitulation of Menorca and the signing of the Treaty of Capdepera.[146] After the surrender, Menorca remained in Muslim hands, but after the signing of the treaty of vassalage and the payment of taxes on the Miquel Nunis tower in the current Capdepera, on 17 June 1231, it became a tributary to the king of Majorca.[147] The island was finally taken in 1287 by Alfonso III of Aragon.

The conquest of Ibiza was appointed by James I to the archbishop of Tarragona Guillem de Montgrí, his brother Bernardo de Santa Eugénia, Count of Roussillon, Nuño Sánchez, and the Count of Urgel, Pedro I.[148] The islands were taken on 8 August 1235 and incorporated into the Kingdom of Majorca. The repopulation was carried out by people from Ampurdán.

Consequences

At first, the new Christian city was divided into two parishes: Santa Eulalia and San Miguel, functioning as administrative, labor and spiritual centres. The latter parish is considered by Majorcan historians as the oldest temple in Palma because its construction was carried out on a Muslim mosque after the invasion, although with minor changes in the original structure to adapt it to Christian worship.[149]

Subsequently, Majorca was constituted as a territory of the Crown of Aragon, under the name "regnum Maioricarum et insulae adyacentes".[51] At first they began using the Catalan system known as usages, or usatges, as the laws of the island, and the regime called "Universitat de la Ciutat i Regne de Mallorca"[n. 10] was also established for the City of Majorca. Medina Mayurqa was renamed "Ciutat de Mallorca or Mallorques" ("Ciudad de Mallorca" in Catalan) because James I endowed it with a municipality covering the whole island.

Subsequently, the city experienced a period of economic prosperity due to its privileged geographical location, ideal for trade with North Africa, Italy and the rest of the Mediterranean.

On 29 September 1231, contravening the pact with the nobles, James I exchanged the kingdom of Majorca for lands in Urgel with his uncle, Prince Peter I of Portugal,[19]: 22 an agreement that was finalized on 9 May 1232, the prince being assigned 103 royal agricultural estates and serving as lord over the island.[19]: 25

The criminal justice system began to make use of new tactics that gradually became imposing. In the letter of repopulation, archaic provisions were added, self-governance arrangements were admitted, and the aggressors who had been injured by the use of the word "renegat" (renegade) or "cugut" (cuckold) received impunity.[150] It also allowed for the perpetrator and victim of a crime to agree to settle their differences via financial compensation.[150] From the moment these provisions were added, due to the repopulation letters, there were notaries public. One of the first to hold this office, which had identical characteristics to those in Catalonia, was Guillem Company; this appears in a 14 August 1231 document.[151] Both James I and the rest of the judicial lords established a notary that would document judicial and property acts within their jurisdiction, whose role came with financial compensation as perceived from the rates that corresponded to deeds authorized to the holder.[150]

Islam was oppressed after the conquest.[152][153] Although not all Muslims remained in captivity, mechanisms were not provided for their conversion to Christianity, nor were they allowed to express their religion publicly.[152] Those who collaborated with the invasion received special treatment and retained their status as free men and could pursue crafts or trade, and many others were sold into slavery.[152]

Soon, the beneficiaries were able to take advantage of the acquisitions. The Knights Templar were allowed to settle 30 Saracen families who participated in the olive harvest, and at the same time, through a pact with the Jews in which they guaranteed water supply, the latter were able to learn to draw navigational charts.[154]

Taxation as a public mechanism for detraction was still not formalized. The major source of income for the king was feudal in nature. Another source of revenue was payments from non-Christian communities by way of trade impositions.[155]

The mosque was used as a Christian church until about 1300 when construction began on the Santa Maria cathedral, known for being built closer to the sea than any other Gothic cathedral, and also for having one of the world's largest rose windows, popularly known as the Gothic eye.[n. 11]

The city's water supply system consisted of ditches entering through the main gate and flowing to the royal palace. It was feudalized and became privately owned by royal grant, its distribution carried out through concession fees imposed by each owner.[156]

After the population decline resulting from the Black Death, pastoral activities were enhanced and helped to provide low-cost supplies to the local textile industry and improved their ability to sell products to Italian cities. The city did not lose its function as a transit hub for commercial shipping activity in North Africa.[9]

Although the Romans had introduced the craft of growing grapes for winemaking, the Moorish population limited its consumption based on Qur'anic prohibitions. Its cultivation was reintroduced and assisted by the Aragonese Cortes by way of a planting licensing regime, which granted a period of relative prosperity.[157]

The process of land occupation was slow. For 15 years after the conquest there were plots where only a quarter of the available land was cultivated, while most of the people settled in the capital city and its surrounding areas.[158] In 1270, the indigenous Muslim population that had been conquered by the invaders was extinguished, expelled or replaced by continental settlers or slaves.[159]

After the death of James I, the kingdom, along with other possessions in southern France, was inherited by his son James II, who became the king of Majorca, independent of the Crown of Aragon until its subsequent return to the Crown. Some streets of Palma commemorate James I's name and this chapter of the island's history, including the Abu Yahya square. The "calle 31 de diciembre" (December 31 Street) crosses the square and refers to the date of the triumphant entry of the Christian troops into the city.

Legacy

Events

In 2009, a tour with 19 panels in four languages was opened; known as "the landing routes", it involves a walk around the outskirts of the town of Santa Ponsa along three different routes: the Christian route, the Muslim route and the battle route.[160]

On 9 September 2010, during the commemoration of the 781 years since the landing, Carlos Delgado Truyols, the mayor of the municipality of Calvia, reiterated his support for historical approaches: "The conquest of Majorca, from the political point of view was not a Catalan conquest, but it was of a plural nature and involved Christendom." He also reclaimed the Majorcan dialect of Catalan as the official language of Majorca.[161]

In 2010, the remains of a Berber woman of the era were found in the town of Arta. It is estimated that she had taken refuge in a cave with the keys to her home, along with more than two dozen people, who are believed to have been unaware that the island had been invaded three months earlier.[159]

The capture of the capital is annually commemorated during the "Festa de l'Estendart" on the 30 and 31 of December. This festival was declared "Bien de Interés Cultural". Since the thirteenth century, it has been considered one of the oldest civil festivals in Europe. During the event, which usually results in protests by nationalist groups, a proclamation is made and a floral offering made to the statue of James I located in the Plaza of Spain in Palma.[162] It is believed that the name of the festival refers to the soldier that placed the royal standard in the tower and told the rest of the Christian troops that they could storm the city.[163]

Literature

In the folk literature of Catalan-speaking territories there is a wide range of stories and legends featuring James I, such as one that is told of the king attending a banquet held at the residence of Pere Martell. In the middle of the banquet he is said to have ordered them to leave his food and drink and to not touch anything until his victorious return from the island.[164]

Among his troops, James I also had the presence of Almogavars, mercenaries who lived for battle and war and are usually sold to the highest bidder.

The attire of the Christian troops consisted of a hemispherical helmet reinforced by a ring from which a kind of protector for the nose could be hung. Their helmets were made of wrought iron plates that after a period of honing were often painted mainly to improve their durability, but also as a means of identifying the warriors wearing them.[165]

Art

Although in the late Middle Ages the predominant architectural style of the bourgeois class was Gothic, both James I and the monarchs who succeeded him on the throne of Majorca were devoted to developing policies and promoting commercial maritime trade.[166] The commercial character of this policy was developed by Catalans, Valencians and Majorcans, while the kingdom of Aragon was assimilated in part into the social and economic patterns of Castile, engaged in agriculture, livestock and the dominance of the nobility.[166] Within Majorca there began to emerge a massive development of civil Gothic architecture which became abundant in the area. The rich and powerful bourgeois built palaces, held auctions and county councils contrary to the pretensions of the Aragonese monarchs.[166]

During the Christian conquest, many Islamic architectural works were destroyed and only the baths located in the garden of the Palma mansion of Can Fontirroig survive.[167] Its construction date is estimated to be during the tenth century and some believe that it could have been attached to a Muslim palace.[dead link][168] It maintained its well-preserved arches and 12 columns decorated with capitals of an uneven design and a square hall-topped dome.[168]

In terms of paintings, there have been many works of art made throughout the history of the island. Between 1285 and 1290, the reception hall of the Royal Palace of Barcelona was painted with images of the conquest; three canvases on which the cavalry, labourers, spearmen and archers are depicted have been conserved. There are also fragments of other paintings in the Palacio Aguilar, representing the meeting of the courts of Barcelona in 1228.[169]

With the intent of decorating its halls, the cultural society, the Mallorcan Circle, convened a painting competition in 1897 regarding the events on the battlefield during the conquest. One of two winning entries, entitled Rendición del walí de Mallorca al rey Jaime I (Surrender of the wali of Majorca to King James I), done on a huge canvas by Richard Anckermann, reflected the triumphant entry into the city by James on horseback and dressed in a coat of mail. The other entry depicted the surrender of the Vali.[96]

Mysticism

In the Llibre dels Fets appear several mentions of Jaume I to the Divinity. For example, faced with the arrival to Majorca, says:

And see the virtue of God, which one is, that with that wind with which we were going to Majorca we could not take to Pollença as it had been undertaken, and what we thought that was contrary helped us, that those ships that were bad to luff they all went with that wind towards la Palomera, where we were, that no ship nor boat was lost, and nobody failed.

Already for 2012, appeared a sequence evoking the event that was related to an own mystical experience. In an open letter to the Bishop of Majorca,[170] it is said:

The sequence is in the list of contributions of "Sincronia Silenciosa [ca]", in the Catalan version of Wikipedia (Viquipèdia). On December 31 (the day of the Festa de l'Estendard) began to write in the discussion of the article of the Balearic capital, on its denomination, later the name of the article of the Cathedral was changed and the one of the Mancomunidades was created, fact that supposed a division of the island, something that appears in the Llibre dels Fets, although not in the same form. With that symbolically manifested, I noticed the action of an intelligence beyond... And I received more information...

See also

Notes

- ^ Montpellier, Narbona, Marsella and Génova also participated and subsequently obtained profits from the conquest.

- ^ Lomax

- ^ According to The Crònica de Bernat Desclot

- ^ José A. Sesma

- ^ A cuartera is a dry measure which equates to approximately fifteen pecks

- ^ Salrach

- ^ According to Salrach, some 300 men.

- ^ Barcelona, Tarragona, Marsella, Lleida, Girona, Besalú, Villafranca, Montblanc, Cervera, Lleida, Prades, Caldes, Piera, Tàrrega, Vilamajor and Argelès-sur-Mer.

- ^ Died during the Battle of Portopí.

- ^ Established in the Carta de Privilegis i Franqueses of 1249, following the format of similar letters from Tortosa, Lleida or Agramunt.

- ^ Most guidebooks on Palma present inaccurate information, in reference to the dimensions of the glass surface. There are some Gothic cathedrals in Europe with rose windows larger in diameter, although the glass area is less than that of Palma. Of the Strasbourg Cathedral with a diameter of 15 metres (see the book Merveilleuses cathédrales de France, (Magnificent cathedrals of France), ISBN 2-85961-122-3), and also those in Notre Dame de Paris, whose northern and southern rose windows, built in 1250 and 1260, respectively, and have a diameter of 12.90 metres, see Notre-Dame de Paris.

References

- ^ Vinas, Agnes i Robert: La conquesta de Mallorca (La caiguda de Mayûrqa segons Ibn'Amira al Mahzûmi) (The Conquest of Majorca)

- ^ Álvaro Santamaría. "Precisiones sobre la expansión marítima de la Corona de Aragon (Details of the maritime expansion of the Crown of Aragon)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 194. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ Consell de Mallorca (2010). "La conquista catalana (The Catalan Conquest)". Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ CCRTV. "LLIBRE DEL REPARTIMENT (segle XIII)" (in Catalan). Archived from the original on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ^ "La gran expansión cristiana del siglo XIII (The great Christian expansion of the thirteenth century)". August 2005. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ Álvaro Santamaría. "Creación de la Corona de Mallorca (Creation of the Crown of Majorca)" (in Spanish). p. 143. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ^ a b c d Vicente Ángel Álvarez Palenzuela (November 2002). Historia de España de la Edad Media (History of Spain in the Middle Ages) (in Spanish). Book Print Digital. p. 491. ISBN 9788434466685. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ Jorge Maíz Chacón (2006). "Los judiós mallorquines en el comercio y en las redes de intercambio valencianas y mediterráneas del medievo (Majorcan Jews in trade and Valencian and Mediterranean exchange networks of the Middle Ages)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 76. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ a b c Carlos López Rodríguez. "Algunas observaciones acerca del comercio valenciano en el siglo XV a la luz de la obra de David Abulafia. (Some observations on Valencian trade in the fifteenth century in light of the work by David Abulafia)" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archivo del reino de Valencia. pp. 362–363. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ a b Consell de Mallorca (2010). "Las dominaciones bizantina e islámica (The Byzantine and Islamic domination)" (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ^ "Mallorca y los Vándalos y Bizantinos (Majorca and the Vandals and Byzantines)" (in Spanish). Mallorca Incógnita. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ^ a b "La ciudad Medieval (The Medieval City)" (in Spanish). Mallorca Medieval. Archived from the original on 10 November 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ "Dominación árabe de Mallorca (Arab domination of Majorca)" (in Spanish). MCA travel. Archived from the original on 10 November 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ Henri Pirenne (1933). "Historia Económica Y Social De La Edad Media (Economic and Social History of the Middle Ages)" (in Spanish). p. 8. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ a b Legado andalusí; Hamid Triki (May 2003). Itinerario cultural de Almorávides y Almohades: Magreb y Península Ibérica (Cultural Itinerary of the Almoravids and Almohads: Maghreb and the Iberian Peninsula) (in Spanish). Junta de Andalucía. p. 438. ISBN 9788493061500. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ a b c Javier Lacosta (16 September 1999). "Mallorca 1229: la visión de los vencidos (Majorca 1229: vision of the vanquished)" (in Spanish). Junta islámica. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ "Mallorca Musulmana (Muslim Majorca)" (in Spanish). Mallorca incógnita. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ Miguel Ramis (2003). "El Islam I: Breve historia y Tipos de edifícios (The I Islam: Brief history and types of buildings)" (in Spanish). Artifex. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Antonio Ortega Villoslada (2008). El reino de Mallorca y el mundo Atlántico (The kingdom of Majorca and the Atlantic World) (in Spanish). Netbiblo. ISBN 9788497453264. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ "Ramón Berenguer III el Grande (Ramon Berenguer III the Great)" (in Spanish). Biografías y vidas. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Marcel Mañé. "Los nombres Cataluña y catalán (Catalonia and Catalan names)" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ Ana Isabel Carrasco Manchado, María del Pilar Rábade Obradó (2008). Pecar en la Edad Media (Sin in the Middle Ages) (in Spanish). Sílex. p. 86. ISBN 9788477372073. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ a b Jesús Pabón y Suarez de Urbina (1976). Boletín de la real academia de la historia. Tomo CLXXIII (Bulletin from the Royal Academy of History. Volume CLXXIII). Maestre. p. 46. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ María del Pilar Rábade Obradó, Eloísa Ramírez Vaquero (2005). La dinámica política (The political dynamic) (in Spanish). Ediciones Istmo. p. 403. ISBN 9788470904332. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ "La segunda cruzada (The second crusade)" (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^ "Muhammad ibn Ali ibn Ganiya" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^ a b "La Mallorca musulmana y la visión de los vencidos. (Muslim Majorca and the vision of the conquered)" (in Spanish). Amarre baleares. Archived from the original on 16 November 2010. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ "Molinos de Mallorca. (Mills of Majorca)" (in Spanish). MasMallorca.es. 21 October 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Javier Martos (5 September 2010). "El Morrón del Zagalete desde el cortijo de Benamorabe (Casares). (The Morrón of Zagalete from the Benamorabe Cortijo)" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ Enrique Martínez Ruíz; Emilio de Diego (2000). Del imperio almohade al nacimiento de Granada (1200–1265). (From the Almohad empire to the birth of Granada) (in Spanish). Ediciones AKAL. p. 100. ISBN 9788470903496. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ Mario Hernández Sánchez-Barba (1995). España, historia de una nación. (Spain, History of a nation) (in Spanish). Complutense. p. 72. ISBN 9788489365346. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ^ Miguel Bennasar Barceló (May 2005). "La conquista de las Baleares por Jaime I (The conquest of the Balearic Islands by James I)" (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad de Castellón. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ Jorge Maíz Chacón (2005). "Las expresiones de la violencia en la conquista de Mallorca. (Expressions of violence in the conquest of Majorca)" (in Spanish). U.N.E.D. – C.A. Illes Balears. p. 4. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ^ Joseph Pérez (June 2000). La corona de Aragón. (The Crown of Aragon) (in Spanish). Crítica. p. 77. ISBN 9788484320913. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m María del Pilar Rábade Obradó, Eloísa Ramírez Vaquero (2005). La dinámica política. (The political dynamic) (in Spanish). Ediciones Istmo. p. 400. ISBN 9788470904332. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ Julián Segarra Esbrí (2004). "La forja de una estrategia. (The forging of a strategy)". Lo Lleó del Maestrat. Archived from the original on 30 June 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ Rafel Montaner Valencia (29 November 2009). "Un país saqueado por piratas. (A country ravaged by pirates)" (in Spanish). Levante-emv. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ Orden Bonaria (6 October 2010). "Literatura y Sociedad en el Mundo Románico Hispánico (Literature and Society in the Hispanic Romanesque World)" (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ Guillermo Fatás y Guillermo Redondo (1995). "Blasón de Aragón" (in Spanish). Zaragoza, Diputación General de Aragón. pp. 101–102. Archived from the original on 2012-01-31.

- ^ Juan Torres Fontes. "La delimitación del sudeste peninsular" (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad de Murcia. p. 23. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ^ a b Prim Bertrán Roigé. "Oligarquías y familias en Cataluña (Oligarchies and families in Catalonia)" (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad de Barcelona. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ Llibre dels Feyts.

- ^ a b Gabriel Ensenyat. "La conquista de Madina Mayurqa (The conquest of Madina Mayurga)" (in Spanish). Diario de Mallorca. Archived from the original on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ^ Xavier Renedo. "Els discurs de les corts (The discourses of the Courts)" (PDF) (in Catalan). p. 1. Retrieved 25 December 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Francisco Murillo Ferrol (1983). Informe sociológico sobre el cambio social en España, 1975/1983, Volumen 2 (in Spanish). Euramérica. p. 651. ISBN 9788424003074. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ Rafael Alarcón Herrera (2004). La huella de los templarios (The footprint of the Templars) (in Spanish). Robinbook. p. 94. ISBN 9788479277222. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ Lo racó del temple. "El Temple en la Corona de Aragón (The Temple in the Crown of Aragon)" (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ J. García de la Torre. "Los templarios entre la realidad y el mito". Dto Ciencias Humanas. p. 2. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- ^ Salvador Claramunt. "La nobleza en Cataluña durante el reinado de Jaime I (The nobility in Catalonia during the reign of James I)" (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad de Barcelona. p. 7. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ Manuel Sánchez Martínez. "Negociación y fiscalidad en Cataluña a mediados del siglo XIV" (PDF) (in Spanish). Institución Milá y Fontanals. p. 2. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- ^ a b c José Hinojosa Montalvo. "Jaime I el Conquistador (Jaime I the Conqueror)" (in Spanish). Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ Guillem Rosselló Bordoy (9 December 2007). "La 'Mallorca musulmana' (Muslim Majorca)" (in Spanish). Diario de Palma. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ Martín Alvira Cabrer. "Guerra e ideología en la España del siglo XIII: la conquista de Mallorca según la crónica de Bernat Desclot (War and ideology in thirteenth century Spain: the conquest of Majorca according to the chronicles of Bernat Desclot)" (in Spanish). ucm. p. 40. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ Josep Salat (1818). Tratado de las monedas labradas en el Principado de Cataluña (in Spanish). Antonio Brusi. p. 85. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ "l'ajut de Barcelona (Aid from Barcelona)" (in Catalan). Archived from the original on 27 August 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ Álvaro Santamaría (1989). "Repoblación y sociedad en el reino de Mallorca (Repopulation and society in the Majorcan Kingdom)" (PDF) (in Spanish). Facultad de geografía e historia. p. 2. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ Aurelio Mena Hornero. "La invasión de los francos (The invasion of the Francos)" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Hans-Jörgen Döhla; Raquel Montero-Muñoz (2008). Lenguas en diálogo: el iberromance y su diversidad lingüística y literaria (Languages in dialogue: the iberoromance and its linguistic and literary diversity) (in Spanish). Iberoamericana. p. 477. ISBN 9788484893660. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ Yom Tov Assis. "Los judíos y la reconquista (The Jews and the reconquista)" (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad hebrea de Jerusalén. p. 334. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ Jaume Riera Sans. "Jaime I y los judíos de Cataluña (James I and the Jews from Catalonia)" (PDF). Archivo de la Corona de Aragón. p. 1. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Gabriel Ensenyat Pujols (2005). "Llibre del fets (Book of Facts)" (PDF) (in Catalan). Hora Nova. Retrieved 9 November 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ María Luz Rodrigo Esteban. "La sociedad en Aragón y Cataluña en el reinado de Jaime I (Aragonese and Catalan society during the reign of James I)" (PDF) (in Spanish). Institución Fernando el católico. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ a b "Proposta de la conquesta en el sopar de Pere Martell (Proposal for the conquest at the Peter Martell dinner)". Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ "Pallarés". Grupo Zeta. 1998. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ Ferran Soldevila; Jordi Bruguera (2007). Les quatre grans croniques: Llibre dels feits del rei En Jaume (The four great chronicles: Book of the Feito of King James) (in Catalan). Limpergraf. p. 164. ISBN 9788472839014. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ a b La forja dels Països Catalans

- ^ José Francisco López Bonet (June 2008). "Para una historia fiscal de la Mallorca cristiana (To a fiscal history of Christian Majorca)" (in Spanish). Universidad de las islas Baleares. p. 104. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ Luis Rubió García (1977). Reflexiones sobre la lengua catalana (Reflections on the Catalan language). Universidad de Murcia. p. 21. ISBN 9788460010555. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ Joaquim María Bover de Rosselló (1838). Memoria de los pobladores de Mallorca después de la última conquista por Don Jaime I, y noticia de las heredades asignadas a cada uno de ellos en el reparto general de la isla (Report on the inhabitants of Majorca after the final conquest by James I, and news of the estates assigned to each of them in the general division of the island). Gelabert. p. 76. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ Francisco Saulo Rodríguez Lajusticia (2008). "Aragoneses con propiedades en el reino de Valencia en época de Jaime I" (in Spanish). Universidad de Zaragoza. p. 681. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ María Barceló Crespí. "Aragoneses en Mallorca bajomedieval (Aragonese in Lower Middle Age Majorca)" (in Spanish). Universidad de las islas Baleares. p. 2. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- ^ "De la prehistoria hasta Jaime I (On prehistory up to James I)". Noltros.com. Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ José Cervera Pery. "Un Cervera en la conquista de Mallorca" (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ Real Academia de la Historia (1817). Memorias de la Real Academia de la Historia, Volume 5 (in Spanish). p. 115. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ Rialp (1981). Los Trastamara y la Unidad Española (in Spanish). Ediciones Rialp. p. 126. ISBN 9788432121005. Retrieved 10 October 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d Juan de Mariana; Víctor Gebhardt (1862). Historia general de España y de sus Indias (in Spanish). Librería del Plus Ultra, Barcelona. Retrieved 15 March 2011.