Coup of June 1907

The Coup of June 1907, sometimes known as Stolypin's Coup (Russian: Третьеиюньский переворот, romanized: Tretyeiyunskiy perevorot "Coup of June 3rd"), is the name commonly given to the dissolution of the Second State Duma of the Russian Empire, the arrest of some its members and a fundamental change in the Russian electoral law by Tsar Nicholas II on 16 June [O.S. 3 June] 1907. This act is considered by many historians to mark the end of the Russian Revolution of 1905, and was the subject of intense subsequent debate as to its legality. It also created a fundamental shift in the makeup of future Dumas in the Russian Empire: whereas previous laws had given peasants and other lower-class people a larger proportion of electors to the Duma, the new law transferred this to the propertied classes, in an effort to avoid election of the large number of liberal and revolutionary deputies who had dominated the First and Second Dumas. Although it largely succeeded in this objective, it ultimately failed to preserve the Imperial system, which ceased to exist during the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Background

During the 1905 Revolution, the autocratic regime of Nicholas II was persuaded to adopt a form of constitutionalism, in an effort to preserve itself and keep the nation from sliding into outright anarchism. Nicholas first issued what became known as the October Manifesto on 30 October [O.S. 17 October] 1905 promising basic civil rights and the creation of a parliament, without whose approval no laws were to be enacted in Russia.[1] A new Fundamental Law was issued on 06 May [O.S. 23 April] of the following year, in which the State Duma was established as the lower chamber of a bicameral parliament (the State Council of the Russian Empire forming the upper house). This Duma thus became the first genuine attempt at parliamentary government in Russia.[2] Whereas the Council of State was partly appointed by the Emperor and partly elected by various governmental, commercial and clerical organizations, the Duma was to be elected by Russians of various social classes through a complex system of indirect elections.[3] Initially, the electoral system was drawn up to give a sizable number of electors to the peasants, who were seen as loyal to the Tsarist regime.

While many revolutionaries rejected the Emperor's concessions, most Russians decided to give the new system a chance. However, public faith in the new order was shaken by a fresh Manifesto, issued on 05 March [O.S. 20 February] 1906 ahead of the new Fundamental Law, which severely limited the rights of the newly constituted Duma. Since the absolute power of the Emperor did not formally end until his promulgation of the Fundamental Law itself on 06 May [O.S. 23 April] 1906, the legality of this act could not be challenged by the new legislature. Furthermore, the newly promised civil liberties—freedom of press, assembly and expression, among others—had been greatly reduced during anti-revolutionary operations in that same year.

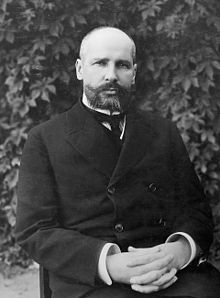

Nicholas II opened the First Duma on 10 May [O.S. 27 April] 1906 with a speech from the throne in the Winter Palace. While he and his ministers hoped to keep the Duma quiescent, the deputies refused to cooperate: they introduced bills for agrarian reform, which were strenuously opposed by the landlords, together with other radical legislative proposals far beyond anything the Tsarist regime was prepared to accept. He dissolved the First Duma on 21 July [O.S. 8 July] 1906 but since elections for the Second Duma returned even more radicals than before, the impasse between legislature and executive continued. About 20% of seats in the Second Duma were taken by Socialists: Mensheviks, Bolsheviks (both factions of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party), Popular Socialists and Socialist Revolutionaries, all of whom had boycotted the elections for the First Duma. Unable to build a working relationship with the new Duma, the Imperial government, under newly appointed Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin, set about finding an excuse to dissolve it.

The coup

The desired pretext came when the government became aware of ongoing revolutionary agitation among Tsarist soldiers; this agitation was often carried out by the members of the RSDLP. On June 2, the imperial government demanded that the Duma hand over 55 Social Democratic deputies, who had (like all the members of the Duma) been guaranteed parliamentary immunity by the Fundamental Law, unless stripped of it by the legislature itself. Impatient at the Duma's lack of cooperation, it chose to arrest them anyway on the night of June 3, without awaiting the decision of a Duma commission set up to investigate the government's accusations. On June 3 the Duma was formally dissolved by Imperial Manifesto followed by Imperial edict (ukase), with Prime Minister Stolypin playing an important role in this act.[4]

This action, which was perfectly legal according to the Fundamental Law (which gave the Tsar unlimited authority to dismiss the Duma at any time, for any reason that suited him),[5] was followed by a dubious political maneuver. On June 3 a new electoral law was published, entirely on the Tsar's authority and without the consent of the Legislature. According to the new scheme, the wealthier landlords obtained sixty percent of the electors for the Duma; peasants got twenty-two percent, while merchants got fifteen percent and the remaining three percent went to the urban proletariat.[6] Areas such as Central Asia were deprived of representation altogether, with the Tsar claiming that the new Duma must be "Russian in spirit", and that non-Russians must never be accorded a "decisive influence" over "purely Russian questions".[7]

Legal challenges

The legality of this act was immediately challenged: according to the October Manifesto, new laws could not be enacted without the approval of the Duma,[8] and neither Nicholas nor Stolypin had obtained the Duma's agreement prior to issuing this decree. The Fundamental Law did permit the Tsar to implement or change new laws without the Duma's consent, in intervals between sessions of the Duma (which is when the "coup" law was enacted), but these were supposed to be submitted to the new Duma within two months, and were subject to that Duma's power to suspend or repeal them.[9] Furthermore, no such edict could ever make any changes in the Fundamental Law itself, which required not just the emperor's initiative but also the Duma's approval.[10] Hence, the Tsar's new electoral statute had been enacted contrary to his own Fundamental Law. This raised the question of whether Russia was fundamentally a state ruled under an immutable organic statute (the Fundamental Law), or one still ruled by an all-powerful monarch.

The Tsar's government countered by insisting that since the Emperor had granted the Fundamental Law to begin with, he had the God-given right to unilaterally alter it (even though the Fundamental Law clearly said otherwise) in extraordinary instances, such as Nicholas claimed this to be. The manifesto of June 3, 1907 announcing this change specifically appealed to the Tsar's "historical authority" as the legal basis for these changes, which Nicholas asserted "cannot be enacted through the ordinary legislative route" since the Second Duma had been "pronounced unsatisfactory" by him.[11]

The Tsar clearly indicated that his own authority, which he claimed to have received from God himself, superseded the authority of any law, even the Fundamental Law itself, which he himself had granted.[12] This convinced many Russians that Nicholas had never embraced constitutionalism to begin with and that Russia ultimately remained an absolute autocracy hiding behind the facade of a constitution. Thus, the term "coup" came to be used to refer to the emperor's act even if it was not a coup d'état in the usual sense.

Legacy

Contrary to the expectations (and the hopes) of some deputies, the so-called "coup d'état" of June 1907 did not cause the resumption of the revolutionary movement. While SRs resumed the acts of individual terror, the number of such acts was relatively small. Since Russia remained relatively quiet, even in the face of the Tsar's contravening of the new Russian Constitution, June 3, 1907 is considered the date of the end of the first Russian revolution.

The Tsar's new electoral law ensured that all future Dumas would remain under the control of the higher classes of society, but this did not ultimately prevent the Duma from taking an important role in the Tsar's eventual overthrow in the February Revolution of 1917. Nicholas' heavy-handed actions in the "coup" crisis irreparably damaged his image (already battered from previous policies he had pursued). This, in turn, caused many of his subjects to eagerly embrace the next revolution when it finally came.

Notes

- ^ October Manifesto

- ^ "Duma." Encyclopædia Britannica from Encyclopædia Britannica 2007 Ultimate Reference Suite. (2009).

- ^ Fundamental Laws, Article 100. See also The Russian Revolution of 1917: Causes, section "A".

- ^ "Stolypin, Pyotr Arkadyevich." Encyclopædia Britannica from Encyclopædia Britannica 2007 Ultimate Reference Suite. (2009)

- ^ Fundamental Laws, Article 105.

- ^ The Russian Revolution of 1917: Causes, section A, subsection 3.

- ^ Imperial Manifesto of June 3, 1907.

- ^ Fundamental Laws, Article 86.

- ^ Fundamental Laws, Article 87.

- ^ Fundamental Laws, Articles 8, 87 and 107.

- ^ Imperial Manifesto of June 3, 1907.

- ^ Imperial Manifesto of June 3, 1907,