Cusco

Cusco | |

|---|---|

| Cusco or Cuzco Qosqo or Qusqu (Quechua) | |

| Nickname(s): La Ciudad Imperial (The Imperial City), El Ombligo del Mundo (The Navel of the World) | |

| Anthem: Himno del Cusco Qosqo yupaychana taki (English: "Anthem of Cusco") | |

Districts of Cusco | |

| Coordinates: 13°31′30″S 71°58′20″W / 13.52500°S 71.97222°W | |

| Country | Peru |

| Region | Cusco |

| Province | Cusco |

| Founded | March 23, 1534[1] |

| Founded by | Francisco Pizarro |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Víctor G. Boluarte Medina |

| Area | |

• Total | 385.1 km2 (148.7 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 3,399 m (11,152 ft) |

| Population (2017) | |

• Total | 428,450 |

• Estimate (2015)[2] | 427,218 |

| • Density | 1,100/km2 (2,900/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | cuzqueño/a, cusqueño/a |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic groups |

|

| GDP (PPP, constant 2015 values) | |

| • Year | 2023 |

| • Total | $4.2 billion[3] |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (PET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 |

| UBIGEO | 08000 |

| Area code | 84 |

| Official name | City of Cusco |

| Location | Latin America and the Caribbean |

| Criteria | Cultural: iii, iv |

| Reference | 273 |

| Inscription | 1983 (7th Session) |

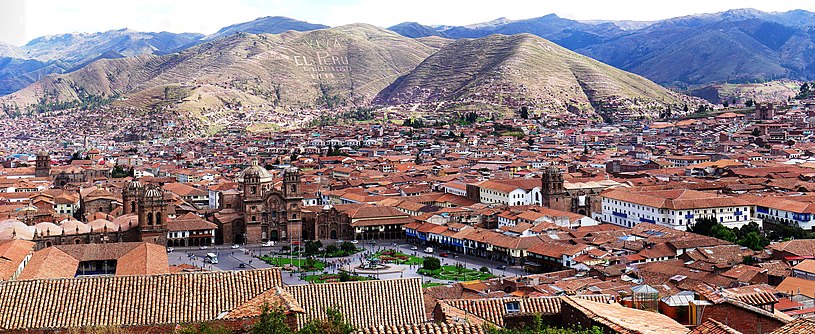

Cusco or Cuzco[d] (Latin American Spanish: [ˈkusko]; Quechua: Qosqo or Qusqu, both pronounced [ˈqosqɔ]) is a city in southeastern Peru, near the Sacred Valley of the Andes mountain range and the Huatanay river. It is the capital of the eponymous province and department. The city is the seventh most populous in Peru; in 2017, it had a population of 428,450. Its elevation is around 3,400 m (11,200 ft).

The city was the capital of the Inca Empire until the 16th-century Spanish conquest. In 1983, Cusco was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO with the title "City of Cusco". It has become a major tourist destination, hosting over 2 million visitors a year and providing passage to numerous Incan ruins, such as Machu Picchu, one of the Seven modern wonders of the world and others. The Constitution of Peru (1993) designates the city as the Historical Capital of Peru.[4]

Spelling and etymology

The indigenous name of this city is Qusqu. Although the name was used in Southern Quechua, its origin is found in the Aymara language. The word is derived from the phrase qusqu wanka ('rock of the owl'), related to the city's foundation myth of the Ayar siblings. According to this legend, Ayar Awqa (Ayar Auca) acquired wings and flew to the site of the future city; there he was transformed into a rock to mark the possession of the land by his ayllu ("lineage"):[5]

Then Ayar Oche stood up, displayed a pair of large wings, and said he should be the one to stay at Guanacaure as an idol in order to speak with their father the Sun. Then they went up on top of the hill. Now at the site where he was to remain as an idol, Ayar Oche raised up in flight toward the heavens so high that they could not see him. He returned and told Ayar Manco that from then on he was to be named Manco Capac. Ayar Oche came from where the Sun was and the Sun had ordered that Ayar Manco take that name and go to the town that they had seen. After this had been stated by the idol, Ayar Oche turned into a stone, just as he was, with his wings. Later Manco Capac went down with Ayar Auca to their settlement...he liked the place now occupied in this city Cuzco. Manco Capac and his companion, with the help of the four women, made a house. Having done this, Manco Capac and his companion, with the four women, planted some land with maize. It is said that they took the maize from the cave, which this lord Manco Capac named Pacaritambo, which means those of origin because...they came out of that cave.[6]: 15–16

The Spanish conquistadors (Spanish soldiers) adopted the local name, transcribing it according to Spanish phonetics as Cuzco or, less often, Cozco. Cuzco was the standard spelling on official documents and chronicles in colonial times,[7] though Cusco was also used. Cuzco, pronounced as in 16th-century Spanish, seems to have been a close approximation to the Cusco Quechua pronunciation of the name at the time.[8]

As both Spanish and Quechua pronunciation have evolved since then, the Spanish pronunciation of 'z' is no longer universally close to the Quechua pronunciation. In 1976, the city mayor signed an ordinance banning the traditional spelling and ordering the use of a new spelling, Cusco, in municipality publications. Nineteen years later, on 23 June 1990, the local authorities formalized a new spelling more closely related to Quechua, Qosqo, but later administrations have not followed suit.[9]

There is no international, official spelling of the city's name. In English-language publications both "s"[10][11] and "z"[12][13] can be found. The Oxford Dictionary of English and Merriam-Webster Dictionary prefer "Cuzco",[14][15] and in scholarly writings "Cuzco" is used more often than "Cusco".[16] The city's international airport code is CUZ, reflecting the earlier Spanish spelling.

Symbols

Flag

The official Flag of Cusco consists of seven horizontal stripes in the colors red, orange, yellow, green, sky blue, blue, and violet, representing the rainbow. This flag was introduced in 1973 by Raúl Montesinos Espejo in celebration of the 25th anniversary of his Tawantinsuyo Radio station. Its popularity led to its official adoption by the Municipality of Cusco in 1978. Since 2021, the flag has also included the golden "Sol de Echenique," a symbol associated with the city's historical identity.[17]

Coat of arms

The Coat of arms of Cusco was officially adopted in 1986 and is used by the city, province, and region of Cusco. The coat of arms incorporates elements from both Inca and Spanish heraldry. Historically, the city's arms included a golden castle on a red field with eight condors surrounding it. The modern design, officially adopted in 1986, features the Sol de Echenique, a golden sun emblem, as the central element, symbolizing the city's connection to its Inca heritage.[18]

Anthem

The Anthem of Cusco was composed by Roberto Ojeda Campana with lyrics by Luis Nieto Miranda in 1944. It was officially adopted as the city's anthem and has been sung at public events since then. In 1991, the anthem was translated into Quechua by Faustino Espinoza Navarro and Mario Mejía Waman. The anthem is performed in both Spanish and Quechua, reflecting the city's cultural diversity and historical significance. In 2019, the Municipality of Cusco declared the performance of the anthem in Quechua at civic events to be of public interest and historical importance.[19]

History

Historical affiliations

Kingdom of Cusco, 1197–1438

Inca Empire, 1438–1532

Kingdom of Spain – Habsburg (Governorate of New Castile and Viceroyalty of Peru), 1532–1700

Kingdom of Spain – Bourbon (Viceroyalty of Peru), 1700–1808

Kingdom of Spain – Bonaparte (Viceroyalty of Peru), 1808–1813

Kingdom of Spain – Bourbon (Viceroyalty of Peru), 1813–1821

Protectorate of Peru, 1821–1822

Peru, 1822–1836

Peru–Bolivian Confederation (Republic of South Peru), 1836–1839

Peru, 1839–present

Killke culture

The Killke people occupied the region from 900 to 1200 AD, prior to the arrival of the Inca in the 13th century. Carbon-14 dating of Saksaywaman, the walled complex outside Cusco, established that Killke constructed the fortress about 1100 AD. The Inca later expanded and occupied the complex in the 13th century. In March 2008, archeologists discovered the ruins of an ancient temple, roadway and aqueduct system at Saksaywaman.[20] The temple covers some 2,700 square feet (250 square meters) and contains 11 rooms thought to have held idols and mummies,[20] establishing its religious purpose. Together with the results of excavations in 2007, when another temple was found at the edge of the fortress, this indicates a longtime religious as well as military use of the facility.[21]

Inca period

Cusco was long an important center of indigenous people. It was the capital of the Inca Empire (13th century – 1532). Many believe that the city was planned as an effigy in the shape of a puma, a sacred animal.[22] How Cusco was specifically built, or how its large stones were quarried and transported to the site remain undetermined. Under the Inca, the city had two sectors: the hurin and hanan. Each was divided to encompass two of the four provinces, Chinchasuyu (NW), Antisuyu (NE), Kuntisuyu (SW) and Qullasuyu (SE). A road led from each quarter to the corresponding quarter of the empire.

Each local leader was required to build a house in the city and live part of the year in Cusco, restricted to the quarter that corresponded to the quarter in which he held territory. After the rule of Pachacuti, when an Inca died, his title went to one son and his property was given to a corporation controlled by his other relatives (split inheritance). Each title holder had to build a new house and add new lands to the empire in order to own land for his family to keep after his death.

According to Inca legend, the city was rebuilt by Sapa Inca Pachacuti, the man who transformed the Kingdom of Cusco from a sleepy city-state into the vast empire of Tawantinsuyu.[23]: 66–69 Archeological evidence, however, points to a slower, more organic growth of the city beginning before Pachacuti. The city was constructed according to a definite plan in which two rivers were channeled around the city. Archeologists have suggested that this city plan was replicated at other sites.

The city fell to the sphere of Huáscar during the Inca Civil War after the death of Huayna Capac in 1528. It was captured by the generals of Atahualpa in April 1532 in the Battle of Quipaipan. Nineteen months later, Spanish explorers invaded the city after kidnapping and murdering Atahualpa (see Battle of Cuzco), and gained control.

Spanish period

The first three Spaniards arrived in the city in May 1533, after the Battle of Cajamarca, collecting for Atahualpa's Ransom Room. On 15 November 1533 Francisco Pizarro officially arrived in Cusco. "The capital of the Incas ... astonished the Spaniards by the beauty of its edifices, the length and regularity of its streets." The great square was surrounded by several palaces, since "each sovereign built a new palace for himself." "The delicacy of the stone work excelled" that of the Spaniards'. The fortress had three parapets and was composed of "heavy masses of rock". "Through the heart of the capital ran a river ... faced with stone. ... The most sumptuous edifice in Cuzco ... was undoubtedly the great temple dedicated to the Sun ... studded with gold plates ... surrounded by convents and dormitories for the priests. ... The palaces were numerous and the troops lost no time in plundering them of their contents, as well as despoiling the religious edifices," including the royal mummies in the Coricancha.[24]: 186–187, 192–193, 216–219

Pizarro ceremoniously gave Manco Inca the Incan fringe as the new Peruvian leader.[24]: 221 Pizarro encouraged some of his men to stay and settle in the city, giving out repartimientos, or land grants to do so.[25]: 46 Alcaldes were established and regidores on 24 March 1534, which included the brothers Gonzalo Pizarro and Juan Pizarro. Pizarro left a garrison of 90 men and departed for Jauja with Manco Inca.[24]: 222, 227

Pizarro renamed it as the "very noble and great city of Cuzco". Buildings often constructed after the Spanish invasion have a mixture of Spanish influence and Inca indigenous architecture, including the Santa Clara and San Blas neighborhoods. The Spanish destroyed many Inca buildings, temples and palaces. They used the remaining walls as bases for the construction of a new city, and this stone masonry is still visible.

Father Vincente de Valverde became the Bishop of Cusco and built his cathedral facing the plaza. He supported construction of the Dominican Order monastery (Santo Domingo Convent) on the ruins of the Corichanca, House of the Sun, and a convent at the former site of the House of the Virgins of the Sun.[24]: 222

During the Siege of Cuzco of 1536 by Manco Inca Yupanqui, a leader of the Sapa Inca, he took control of the city from the Spanish. Although the siege lasted 10 months, it was ultimately unsuccessful. Manco's forces were able to reclaim the city for only a few days. He eventually retreated to Vilcabamba, the capital of the newly established small Neo-Inca State. There his state survived another 36 years but he was never able to return to Cuzco. Throughout the conflict and years of the Spanish colonization of the Americas, many Incas died of smallpox epidemics, as they had no acquired immunity to a disease by then endemic among Europeans.

Cusco was built on layers of cultures. The Tawantinsuyu (former Inca Empire) was built on Killke structures. The Spanish replaced indigenous temples with Catholic churches, and Inca palaces with mansions for the invaders.

Cusco was the center for the Spanish colonization and spread of Christianity in the Andean world. It became very prosperous thanks to agriculture, cattle raising and mining, as well as its trade with Spain. The Spanish colonists constructed many churches and convents, as well as a cathedral, university and archdiocese.

Present

A major earthquake on 21 May 1950 damaged more than one third of the city's structures. The Dominican Priory and Church of Santo Domingo, which were built on top of the impressive Qurikancha (Temple of the Sun), were among the affected colonial era buildings. Inca architecture withstood the earthquake. Many of the old Inca walls were at first thought to have been lost after the earthquake, but the granite retaining walls of the Qurikancha were exposed, as well as those of other ancient structures throughout the city. Restoration work at the Santo Domingo complex exposed the Inca masonry formerly obscured by the superstructure without compromising the integrity of the colonial heritage.[31] Many of the buildings damaged in 1950 had been impacted by an earthquake only nine years previously.[32]

In the 1990s, during the mayoral administration of Mayor Daniel Estrada Pérez, the city underwent a new process of beautification through the restoration of monuments and the construction of plazas, fountains and monuments. Likewise, thanks to the efforts of this authority, various recognitions were achieved, such as the declaration as "Historical Capital of Peru" contained in the text of the Political Constitution of Peru of 1993. It was also decided to change the coat of arms of Cusco, leaving aside the colonial coat of arms and adopting the "Sol de Echenique" as the new coat of arms. Additionally, the change of the official name of the city was proposed to adopt the Quechua word Qosqo, but this change was reversed a few years later. Currently, Cusco is the most important tourist destination in Peru. Under the administration of mayor Daniel Estrada Pérez, a staunch supporter of the Academia Mayor de la Lengua Quechua, between 1983 and 1995 the Quechua name Qosqo was officially adopted for the city. Tourism in the city was drastically affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru and the 2022–2023 Peruvian protests, with the latter event costing the area 10 million soles daily.[33]

Honors

- In 1933, the Congress of Americanists met in La Plata, Argentina, and declared the city as the Archeological Capital of the Americas.

- In 1978, the 7th Convention of Mayors of Great World Cities met in Milan, Italy, and declared Cusco a Cultural Heritage of the World.

- In 1983, UNESCO, in Paris, France, declared the city a World Heritage Site. The Peruvian government declared it the Tourism Capital of Peru and Cultural Heritage of the Nation.

- In 2001, in Cusco, the Latin American Congress of Aldermen and Councillors awarded Cusco the title of Historical Capital of Latinamerica.[34]

- In 2007 the Organización Capital Americana de la Cultura awarded Cusco the title of Cultural Capital of America.[34]

- In 2007, the New7Wonders Foundation designated Machu Picchu one of the New Seven Wonders of the World, following a worldwide poll.[35]

Geography

Location

Cusco extends throughout the Huatanay (or Watanay) river valley. Located on the eastern end of the Knot of Cusco[citation needed], its elevation is around 3,400 m (11,200 ft). To its north is the Vilcabamba mountain range with 4,000–6,000-meter-high (13,000–20,000-foot) mountains. The highest peak is Salcantay (6,271 meters or 20,574 feet) about 60 kilometers (37 miles) northwest of Cusco.[36]

Climate

Cusco has a subtropical highland climate (Köppen Cwb). It is generally dry and temperate, with two defined seasons. Winter occurs from April through September, with abundant sunshine and occasional nighttime freezes; July is the coldest month with an average of 9.7 °C (49.5 °F). Summer occurs from October through March, with warm temperatures and abundant rainfall; November is the warmest month, averaging 13.3 °C (55.9 °F). Although frost and hail are common, the last reported snowfall was in June 1911. Temperatures usually range from 0.2 to 20.9 °C (32.4 to 69.6 °F), but the all-time temperature range is between −8.9 and 30 °C (16.0 and 86.0 °F). Sunshine hours peak in July, the equivalent of January in the Northern Hemisphere. In contrast, February, the equivalent of August in the Northern Hemisphere, has the least sunshine.

In 2006, Cusco was found to be the spot on Earth with the highest average ultraviolet light level.[37]

| Climate data for Cusco (Alejandro Velasco Astete International Airport) (1991–1920, extremes 1931–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 27.8 (82.0) |

26.7 (80.1) |

25.3 (77.5) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.0 (80.6) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.2 (75.6) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.9 (78.6) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.6 (79.9) |

29.9 (85.8) |

29.9 (85.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 19.6 (67.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.3 (68.5) |

20.7 (69.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.9 (71.4) |

20.3 (68.5) |

20.6 (69.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 13.9 (57.0) |

13.7 (56.7) |

13.9 (57.0) |

13.3 (55.9) |

12.1 (53.8) |

11.2 (52.2) |

10.7 (51.3) |

11.9 (53.4) |

13.2 (55.8) |

14.2 (57.6) |

14.8 (58.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

12.5 (54.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 8.1 (46.6) |

7.9 (46.2) |

7.9 (46.2) |

6.3 (43.3) |

3.5 (38.3) |

1.8 (35.2) |

1.3 (34.3) |

2.6 (36.7) |

5.1 (41.2) |

6.9 (44.4) |

7.7 (45.9) |

8.0 (46.4) |

5.6 (42.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.5 (32.9) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 160.0 (6.30) |

132.9 (5.23) |

108.4 (4.27) |

44.4 (1.75) |

8.6 (0.34) |

2.4 (0.09) |

3.9 (0.15) |

8.0 (0.31) |

22.4 (0.88) |

47.3 (1.86) |

78.6 (3.09) |

120.1 (4.73) |

737 (29) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 19 | 15 | 13 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 13 | 16 | 105 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66 | 67 | 66 | 63 | 59 | 55 | 54 | 54 | 56 | 56 | 58 | 62 | 60 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 143 | 121 | 170 | 210 | 239 | 228 | 257 | 236 | 195 | 198 | 195 | 158 | 2,350 |

| Source 1: NOAA (precipitation 1961–1990),[38] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[39] Meteostat[40] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (precipitation days 1970–1990 and humidity 1954–1993)[41] Danish Meteorological Institute (sun 1931–1960)[42] | |||||||||||||

Government

Throughout its history, Cusco has had a marked political importance. During the Inca period, it was the main political center of the region from which the Inca Empire was ruled and where the political and religious elite lived. After its Spanish foundation, it lost prominence due to Francisco Pizarro's decision to establish the capital of the new territories in the city of Lima because it had close access to the sea and communication with the metropolis.[43] However, Cusco continued to be an important city within the viceregal political scheme to the point of being the first city in the entire Viceroyalty to have a bishop.[44] Its participation in the trade routes during the viceroyalty guaranteed its political importance[45] as it remained the capital of the corregimiento established in these territories and, later, of the Intendancy of Cusco and, towards the end of the viceroyalty, of the Royal Audience of Cusco.

During the republic, Cusco's political role languished due to its isolation from the capital, coastline, and trade routes of the 19th and 20th centuries.[46] However, it maintained its status as the main city in southern Peru, although subordinated to the importance that Arequipa was gaining, better connected with the rest of the country. Cusco has always remained the capital of the department of Cusco

Politically, according to the results of elections held in the second half of the 20th century, Cusco has been a stronghold of leftist parties in Peru. In the 1970s and 1980s, the socialist leader Daniel Estrada Pérez brought together this political tendency under the banner of the United Left alliance. Since his death, Cusco has been a major city for parties such as the Peruvian Nationalist Party and the Broad Front for Justice, Life and Liberty, as well as regional movements. Traditional Peruvian parties, such as the Peruvian Aprista Party and Acción Popular, have recorded eventual electoral victories, while those that represent a right-wing political position, such as the Popular Christian Party and Fujimorism itself, have had little presence among the elected authorities.

Demographics

The city had a population of about 348,935 people in 2007 and 428,450 people in 2017 according to INEI.

| City district | Area (km2) |

Population 2017 census (hab) |

Housing (2007) |

Density (hab/km2) |

Elevation (amsl) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuzco | 116.22 | 114,630* | 28,476 | 936.1 | 3,399 | |

| San Jerónimo | 103.34 | 57,075* | 8,942 | 279.2 | 3,244 | |

| San Sebastián | 89.44 | 112,536* | 18,109 | 955.6 | 3,244 | |

| Santiago | 69.72 | 94,756* | 21,168 | 950.6 | 3,400 | |

| Wanchaq | 6.38 | 58,541* | 14,690 | 8,546.1 | 3,366 | |

| Total | 385.1 | 437,538* | 91,385 | 929.76 | — | |

| *Census data conducted by INEI[48][49] | ||||||

Economy

Economic activity in Cuzco includes agriculture, especially maize and native tubers. The local industry is related to extractive activities and to food and beverage products, such as beer, carbonated waters, coffee, chocolates, among others. However, the relevant economic activity of its inhabitants is the reception of tourism, with increasingly better infrastructure and services. It is the second city in this country that has and maintains full employment.

Tourism

Tourism has been the backbone to the Cusco economy since the early 2000s, bringing in more than 1.2 million tourists per year.[50] In 2019, Cusco was the region that reached the highest number of tourists in Peru with more than 2.7 million tourists.[51] In 2002, the income Cusco received from tourism was US$837 million. In 2009, that number increased to US$2.47 billion. [citation needed] Most tourists visiting the city are there to tour the city and the Incan Ruins, especially the top destination, Machu Picchu, which is one of the New Seven Modern Wonders of the World.

In order to keep up with tourist demand, the city is constructing a new airport in Chinchero known as Chinchero International Airport. Its main purpose is for tourists to bypass lay overs through Lima and connect the city to Europe and North America. It will replace the old airport, Alejandro Velasco Astete International Airport.

Culture

Architecture

Due to its antiquity and significance, the center of the city preserves many buildings, squares and streets from pre-Columbian times as well as colonial constructions. That is why the city was declared in 1972 as "Cultural Heritage of the Nation" by Supreme Resolution No. 2900-72-ED.In 1983, during the VII session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, it was decided to declare this area as a World Heritage Site by establishing a central zone that constitutes the World Heritage Site proper and a buffer zone.

One of the characteristics that the Incas achieved with their urban plan in Cusco was the respect for the geographical matrix when building their fabric, since they responded with different design strategies to the rugged topography of the Andean area at 3399 meters above sea level

Language

The native language is Quechua, although the city's inhabitants mostly speak Spanish. The Quechua people are the last living descendants of the Inca Empire.

Museums

Cusco has the following important museums:[52]

- Museo de Arte Precolombino

- Casa Concha Museum (Machu Picchu Museum)

- Museo Inka

- Museo Histórico Regional de Cuzco

- Centro de Textiles Tradicionales del Cuzco or Center of the Traditional Textiles of Cusco in English

- Museum of Sacred, Magical and Medicinal Plants (Museo de plantas sagradas, mágicas y medicinales)[53]

- ChocoMuseo (The Cacao and Chocolate Museum)[54]

There are also some museums located at churches, like the Museum and Convent of San Francisco and the Museum of Qoricancha Temple

Religion

The most common religion in Cusco is Catholicism.

Cuisine

As capital to the Inca Empire, Cusco was an important agricultural region. It was a natural reserve for thousands of native Peruvian species, including around 3,000 varieties of potato cultivated by the people.[55] Fusion and neo-Andean restaurants developed in Cusco, in which the cuisine is prepared with modern techniques and incorporates a blend of traditional Andean and international ingredients.[56] Cuy (guinea pig), a native animal in Cusco, is a popular dish in the city.

The local gastronomy presents a diversified array of dishes resulting from the mestizaje and fusion of its pre-Inca, Inca, colonial, and modern traditions. It is a variation of Andean Peruvian cuisine, although it maintains some typical cultural traits of southern Peru. Although the list of typical dishes may vary among individuals, Tapia and García present a list of foods and beverages usually found in a Cusco picantería:[57]

Foods

- Costillar frito (fried ribs)

- Caldo de panza (tripe soup)

- Panza apanada (breaded tripe)

- Chuleta frita (fried chop)

- Tarwi

- Carne a la parrilla (grilled meat)

- Pecho dorado (golden chest)

- Malaya frita (fried flank steak)

- Churrasco al jugo (juicy steak)

- Estofado de canuto (stewed canuto)

- Ubre apanada (breaded udder)

- Caldo de malaya (flank steak soup)

- Suflé de rocoto (rocoto soufflé)

- Chicharrón (fried pork)

- Choclo con queso (corn with cheese)

- Cuy al horno (baked guinea pig)

- Solterito de kuchicara (kuchicara salad)

- Corazón a la brasa (grilled heart)

Other dishes include chairo, adobo, rocoto relleno, kapchi, lawas or creams made with corn or chuño, and Timpu, a dish originating from Cusco served during Carnival

Beverages

Chiri Uchu

Chiri Uchu is a typical dish of the locality not offered in picanterías, as it is consumed in June during the Cusco festivities of Inti Raymi and, primarily, during the Corpus Christi. It is considered one of the most authentic gastronomic expressions of Cusco as it blends both native flavors of the Andes and those brought by the Spanish conquistadors. It is a cold dish that includes various meats (cuy, boiled chicken, charqui, morcilla (blood sausage), salchicha (sausage)), potatoes, cheese, corn cake, fish roe, and lake algae.[58]

Music

A folkloric institution established in 1924. It is considered the most important folkloric institution in the city[59] and was recognized by the Peruvian government as the first folkloric institution in the country[59] and by the regional government as a Living Cultural Heritage of the Cusco region.[60]

Cusco Symphony Orchestra

It is a permanent artistic group of the Decentralized Directorate of Culture of the Cusco Regional Government, created by Directoral Resolution No. 021/INC-Cusco on March 10, 2009. It performs more than 50 concerts a year and uses the Cusco Municipal Theater.

Sport

Among other events, the Imperial City was a venue for the 2004 Copa América, hosting the third-place match between the Colombia and Uruguay national teams.

The most popular sport in the city is football (soccer), with three main clubs. Cienciano participates in the Liga 1 (First Division) and is the only Peruvian club to win an international tournament, winning the 2003 Copa Sudamericana and 2004 Recopa Sudamericana.

Another historic team is Deportivo Garcilaso, which was promoted to Liga 1 after winning the Copa Perú 2022.

Lastly, there is the Cusco Football Club, formerly known as Real Garcilaso, which played in the First Division from 2012 to 2021 after winning the Copa Perú in 2011. In 2022, it was promoted again to Liga 1 after winning the Second Division of Peru.

Cinema

The International Short Film Festival (FENACO) was an important international film festival in southern Peru, held every November since 2004 in the imperial city of Cusco.[61] Originally, it was a national event dedicated to the short film format (up to 30 minutes in length), with international showcases, hence its name FENACO (Festival Internacional de Cortometrajes), a name popularized in Peru and worldwide to recognize the festival. However, due to the reception and response from filmmakers, producers, and distributors from different countries, it evolved into an international festival, reaching 354 short films in competition from 37 countries in its sixth edition.[61]

Main sites

The indigenous Killke culture built the walled complex of Sacsayhuamán about 1100. The Killke built a major temple near Saksaywaman, as well as an aqueduct (Pukyus) and roadway connecting prehistoric structures. Sacsayhuamán was expanded by the Inca.

The Spanish explorer Pizarro sacked much of the Inca city in 1535. Remains of the palace of the Incas, Qurikancha (the Temple of the Sun), and the Temple of the Virgins of the Sun still stand. Inca buildings and foundations in some cases proved to be stronger during earthquakes than foundations built in present-day Peru. Among the most noteworthy Spanish colonial buildings of the city is the Cathedral of Santo Domingo.

The major nearby Inca sites are Pachacuti's presumed winter home, Machu Picchu, which can be reached on foot by the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu or by train; and the "fortress" at Ollantaytambo.

Less-visited ruins include: Incahuasi, the highest of all Inca sites at 3,980 m (13,060 ft);[62] Vilcabamba, the capital of the Inca after the Spanish capture of Cusco; the sculpture garden at Ñusta Hisp'ana (aka Chuqip'allta, Yuraq Rumi); Tipón, with working water channels in wide terraces; as well as Willkaraqay, Patallaqta, Chuqik'iraw, Moray, Vitcos and many others.

The surrounding area, located in the Watanay Valley, is strong in gold mining and agriculture, including corn, barley, quinoa, tea and coffee.

Cusco's main stadium Estadio Garcilaso de la Vega was one of seven stadiums used when Peru hosted South America's continental soccer championship, the Copa América, in 2004. The stadium is home to one of the country's most successful soccer clubs, Cienciano.

The city is served by Alejandro Velasco Astete International Airport.

Architectural heritage

Because of its antiquity and importance, the city center retains many buildings, plazas, streets and churches from colonial times, and even some pre-Columbian structures, which led to its declaration as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1983. Among the main sights of the city are:

Barrio de San Blas

This neighborhood houses artisans, workshops and craft shops. It is one of the most picturesque sites in the city. Its streets are steep and narrow with old houses built by the Spanish over important Inca foundations. It has an attractive square and the oldest parish church in Cusco, built in 1563, which has a carved wooden pulpit considered the epitome of Colonial era woodwork in Cusco.

The Quechua name of this neighborhood is Tuq'ukachi, which means the opening of the salt.

Hatun Rumiyuq

This street is the most visited by tourists. On the street Hatun Rumiyoq ("the one with the big stone") was the palace of Inca Roca, which was converted to the Archbishop's residence.

Along this street that runs from the Plaza de Armas to the Barrio de San Blas, one can see the Stone of Twelve Angles, which is viewed as a marvel of ancient stonework and has become emblematic of the city's history.

Basílica de la Merced

Its foundation dates from 1536. The first complex was destroyed by the earthquake of 1650. Its rebuilding was completed in 1675.

Its cloisters of Baroque Renaissance style, choir stalls, colonial paintings and wood carvings are highlights, now a popular museum.

Also on view is an elaborate monstrance made of gold and gemstones that weighs 22 kg (49 lb) and is 130 cm (51.18 in) in height.

Cathedral

The first cathedral built in Cusco is the Iglesia del Triunfo, built in 1539 on the foundations of the Palace of Viracocha Inca. Today, this church is an auxiliary chapel of the cathedral.

The main basilica cathedral of the city was built between 1560 and 1664. The main material used was stone, which was extracted from nearby quarries, although some blocks of red granite were taken from the fortress of Saksaywaman.

This great cathedral presents late-Gothic, Baroque and plateresque interiors and has one of the most outstanding examples of colonial goldwork. Its carved wooden altars are also important.

The city developed a distinctive style of painting known as the "Cuzco School" and the cathedral houses a major collection of local artists of the time. The cathedral is known for a Cusco School painting of the Last Supper depicting Jesus and the twelve apostles feasting on guinea pig, a traditional Andean delicacy.

The cathedral is the seat of the Archdiocese of Cuzco.

Plaza de Armas de Cusco

Known as the "Square of the warrior" in the Inca era, this plaza has been the scene of several important events, such as the proclamation by Francisco Pizarro in the conquest of Cuzco.

Similarly, the Plaza de Armas was the scene of the death of Túpac Amaru II, considered the indigenous leader of the resistance.

The Spanish built stone arcades around the plaza which endure to this day. The main cathedral and the Church of La Compañía both open directly onto the plaza.

The cast iron fountain in Plaza de Armas was manufactured by Janes, Beebe & Co.

Iglesia de la Compañía de Jesús

This church (Church of the Society of Jesus), whose construction was initiated by the Jesuits in 1576 on the foundations of the Amarucancha or the palace of the Inca ruler Wayna Qhapaq, is considered one of the best examples of colonial baroque style in the Americas.

Its façade is carved in stone and its main altar is made of carved wood covered with gold leaf. It was built over an underground chapel and has a valuable collection of colonial paintings of the Cusco School.

Qurikancha and Convent of Santo Domingo

The Qurikancha ("golden place") was the most important sanctuary dedicated to the Sun God (Inti) at the time of the Inca Empire. According to ancient chronicles written by Garcilaso de la Vega (chronicler), Qurikancha was said to have featured a large solid golden disc that was studded with precious stones and represented the Inca Sun God – Inti. Spanish chroniclers describe the Sacred Garden in front of the temple as a garden of golden plants with leaves of beaten gold, stems of silver, solid gold corn-cobs and 20 life-size llamas and their herders all in solid gold.[63]

The temple was destroyed by its Spanish invaders who, as they plundered, were determined to rid the city of its wealth, idolaters and shrines. Nowadays, only a curved outer wall and partial ruins of the inner temple remain at the site.

With this structure as a foundation, colonists built the Convent of Santo Domingo in the Renaissance style. The building, with one baroque tower, exceeds the height of many other buildings in this city.

Inside is a large collection of paintings from the Cuzco School.

Infrastructure

Transport

Air

Cusco's main international airport is Alejandro Velasco Astete International Airport, which provides service to 5 domestic destinations and 3 international ones. It is named in honor of Peruvian pilot Alejandro Velasco Astete who was the first person to fly across the Andes in 1925 when he made the first flight from Lima to Cusco. The airport is the second busiest in Peru after Lima's Jorge Chávez International Airport. It will soon be replaced by Chinchero International Airport. which will provide access to North American and Europe.

Rail

Cusco is connected by rail to the cities of Juliaca and Arequipa through the Southern Section of the Southern Railway, whose terminus in the city is the Wánchaq station. Additionally, from the San Pedro station, the South East Section of the Southern Railroad (former Cusco-Santa Ana-Quillabamba Railway) departs from the city, which is the route to the ancient Inca citadel of Machu Picchu. PeruRail is the largest Peruvian railway company and provides service to stations in Cusco.

Road

By road, it is connected to the cities of Puerto Maldonado, Arequipa, Abancay, Juliaca and Puno. The road that connects it with the city of Abancay is also the fastest to reach Lima after a journey of more than 20 hours crossing the departments of Apurímac, Ayacucho, Ica and Lima.

Healthcare

Cusco, as the administrative and economic center of the region, hosts numerous public and private health facilities. Public healthcare is provided by the Ministry of Health, including the Regional Hospital and Hospital Antonio Lorena. Additionally, EsSalud operates several institutions, such as Adolfo Guevara Velazco Hospital, Metropolitan Polyclinic, San Sebastián Polyclinic, Santiago Polyclinic, and La Recoleta Polyclinic.

Twin towns – sister cities

Athens, Greece

Athens, Greece Baguio, Philippines

Baguio, Philippines Bethlehem, Palestine

Bethlehem, Palestine Chartres, France

Chartres, France Copán Ruinas, Honduras

Copán Ruinas, Honduras Cuenca, Ecuador

Cuenca, Ecuador Havana, Cuba

Havana, Cuba Jersey City, United States

Jersey City, United States Jerusalem, Israel

Jerusalem, Israel Kaesong, North Korea

Kaesong, North Korea Kraków, Poland

Kraków, Poland Kyoto, Japan

Kyoto, Japan Mexico City, Mexico

Mexico City, Mexico Moscow, Russia

Moscow, Russia La Paz, Bolivia

La Paz, Bolivia Potosí, Bolivia

Potosí, Bolivia Puebla, Mexico[65]

Puebla, Mexico[65] Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Samarkand, Uzbekistan

Samarkand, Uzbekistan San Miguel de Allende, Mexico[66]

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico[66] Santa Barbara, United States

Santa Barbara, United States Takayama, Japan[67]

Takayama, Japan[67] Tempe, United States[68]

Tempe, United States[68] Xi'an, China

Xi'an, China

See also

- History of Cusco

- List of buildings and structures in Cusco

- Colonial Cusco Painting School

- Governorate of New Castile

- Inca religion in Cusco

- Inca road system

- Iperu, tourist information and assistance

- List of archaeoastronomical sites sorted by country

- PeruRail

- Peru's Challenge

- Pikillaqta

- Santurantikuy

- Tampukancha, Inca religious site

- Tourism in Peru

- Wanakawri

- Centro Qosqo de Arte Nativo

Notes

- ^ Based on the 2017 National Census, which included, for the first time, a question of ethnic self-identification that was addressed to people aged 12 and over considering elements such as their ancestry, their customs and their family origin to visualize and better understand the cultural reality of the country.

- ^ Includes Asháninka, Awajún, Shipibo-Konibo and Shawi.

- ^ Includes Nikkei, Tusan, among others.

- ^ Cusco has been the preferred spelling since 1976; see § Spelling and etymology.

References

- ^ La República (23 March 2020). "Cusco: 486 años de la fundación de la antigua capital Inca". larepublica.pe (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ Perú: Población estimada al 30 de junio y tasa de crecimiento de las ciudades capitales, por departamento, 2011 y 2015. Perú: Estimaciónes y proyecciones de población total por sexo de las principales ciudades, 2012–2015 (Report). Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. March 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ "TelluBase—Peru Fact Sheet (Tellusant Public Service Series)" (PDF). Tellusant. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ "Constitución del Perъ de 1993". Pdba.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo (2007). "Cuzco: La piedra donde se posó la lechuza. Historia de un nombre". Andina. 44. Lima: 143–174. ISSN 0259-9600.

- ^ Betanzos, J., 1996, Narrative of the Incas, Austin: University of Texas Press, ISBN 978-0292755598

- ^ Carrión Ordóñez, Enrique (1990). "Cuzco, con Z". Histórica. XVII. Lima: 267–270.

- ^ Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo (2006). "Cuzco: la piedra donde se posó la lechuza. Historia de un nombre" (PDF). Lexis. 1 (30): 151–52. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ Cuzco Eats: "In the epoch of Daniel Estrada Perez, one of the most influential mayors we have had in this city, the name was changed to Qosqo, reclaiming Quechua pronunciation and spelling. Years later, under other governments the name returned once again to Cusco." 22 Sept. 2014

- ^ "Cusco – Cusco and around Guide". roughguides.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ "The World Factbook". cia.gov. 19 July 2022.

- ^ "City of Cuzco – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. 21 August 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Cuzco Travel Information and Travel Guide – Peru". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of English, 2nd ed, revised, 2009, Oxford University Press, eBook edition, accessed 30 August 2017.

- ^ Merriam-Webster Online|[1], accessed 30 August 2017.

- ^ JSTOR (cuzco) AND la:(eng OR en) has 12,687 articles vs. only 4,168 articles for (cusco) AND la:(eng OR en); JSTOR accessed 20 April 2024.

- ^ "La Bandera del Tahuantisuyo" (PDF). Congreso de la República (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- ^ Angles Vargas, Víctor (1988). Historia del Cusco Colonial Tomo I. Lima: Industrial Gráfica S.A.

- ^ Mendoza, Zoila (2006). Crear y sentir lo nuestro: folclor, identidad regional y nacional en el Cusco, siglo XX (First ed.). Lima: Fondo Editorial de la PUCP. ISBN 9972-42-770-6.

- ^ a b Hearn, Kelly (31 March 2008). "Ancient Temple Discovered Among Inca Ruins". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ "News". Comcast.net<!. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "The history of Cusco". cusco.net<!. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- ^ de Gamboa, P. S., 2015, History of the Incas, Lexington, ISBN 9781463688653

- ^ a b c d Prescott, W. H. (2011). The History of the Conquest of Peru. Digireads.com Publishing, ISBN 9781420941142

- ^ Pizzaro, P. (1571). Relation of the Discovery and Conquest of the Kingdoms of Peru, Vol. 1–2. New York: Cortes Society, RareBooksClub.com, ISBN 9781235937859

- ^ "Il Cvscho, citta principale della provincia del Perv". Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library of the Yale University Library.

- ^ Ingrid Baumgärtner; Nirit Ben-Aryeh Debby; Katrin Kogman-Appel (March 2019). Maps and travel in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. Berlin, Boston: Library of Congress. ISBN 978-3-11-058877-4.

- ^ Karen Ordahl Kupperman (1995). America in European Consciousness, 1493–1750. Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, University of North Carolina Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-8078-4510-3.

- ^ "City of Cuzco". UNESCO World Heritage website.

- ^ Ephraim George Squier (1877). Peru; incidents of travel and exploration in the land of the Incas. Harper & Brothers. p. 431.

- ^ "Koricancha Temple and Santo Domingo Convent – Cusco, Peru". Sacred-destinations.com. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Erickson; et al. "The Cusco, Peru, Earthquake of May 21, 1950". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. Bssa.geoscienceworld.org. p. 97. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Vega, Ysela (6 February 2023). "Cusco sin 4.000 reservas hoteleras y pérdidas de S/10 millones al día". La Republica (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ a b GrupoRPP (22 February 2013). "Títulos honoríficos que ostentan la ciudad del Cusco y Machu Picchu". RPP (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ "Opera House snubbed as new Wonders unveiled". abc.net.au. 8 July 2007.

- ^ "Map of the Andes". zoom-maps.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ^ Liley, J. Ben and McKenzie, Richard L. (April 2006) "Where on Earth has the highest UV?" UV Radiation and its Effects: an update NIWA Science, Hamilton, NZ;

- ^ "Cusco Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ "Station Alejandro Velasco" (in French). Météo Climat. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ "Cuzco Climate : Temperature 1991-2020". Meteostat. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Cuzco, Prov. Cuzco / Peru" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ Cappelen, John; Jensen, Jens. "Peru – Cuzco" (PDF). Climate Data for Selected Stations (1931–1960) (in Danish). Danish Meteorological Institute. p. 209. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ "Fundación de Lima". Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ Angles Vargas, Víctor (1983). Historia del Cusco Colonial Tomo II Libro segundo. Lima: Industrialgrafica S.A.

- ^ "Informe Económico y Social Región Cusco" (PDF). Banco Central de Reserva del Perú. 22–23 May 2009. p. 21. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ Tamayo Herrera, José (1981). Historia social del Cuzco republicano. Lima: Editorial Universo S.A.

- ^ INEI (2018). Resultados Definitivos del departamento de Cusco - Censos Nacionales 2017: XII de Población, VII de Vivienda y III de Comunidades Indígenas. INEI. p. 40. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ "Perú: Perfil Sociodemográfico" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ Censo 2005 INEI Archived 23 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "PERU: New Cusco airport will help boost tourism". Oxford Analytica Daily Brief Service. 10 August 2010. ProQuest 741070699.

- ^ "Llegada de turistas aumentó 8,1% en el 2019".

- ^ Museums in Cusco theonlyperuguide.com

- ^ Museum of Sacred, Magical and Medicinal Plants, Cusco

- ^ Cacao and Chocolate Museum Archived 21 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Cusco

- ^ Leighton, Paula (7 July 2023). "Peru city bans GM to protect native potatoes". scidev.net. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ "Restaurantes". Sazón Perú. 20 November 2007. Archived from the original on 20 November 2007.

- ^ Tapia Peña, Saúl; García Huallpa, Juan Fabrizio (2011). Picanterías típicas para la promoción turística en el barrio de San Blas del Cusco (PDF) (Licentiate thesis). Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco.

- ^ Ramírez, Diana (9 April 2019). "Tradición ancestral: Chiri Uchu". Perú Gastronomía. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ a b Mendoza, Zoila (2006). Crear y sentir lo nuestro: folclor, identidad regional y nacional en el Cuzco, siglo XX (First ed.). Lima: Fondo Editorial de la PUCP. ISBN 9972-42-770-6.

- ^ "Centro Qosqo de Arte Nativo declared Living Cultural Heritage of the Cusco region". Andina. 10 August 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ^ a b National and International Short Film Festival Cusco Peru

- ^ "Photo map of the sites in Upper Puncuyoc – Inca Wasi, cave group, reflection pond and abandoned pegs". bylandwaterandair.com. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ "The Inca City of Cusco: A Fascinating Look at the Most Important City in the Inca Empire". totallylatinamerica.com. 5 July 2013. Archived from the original on 10 July 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "Ciudades Hermanas de Cusco". aatccusco.com (in Spanish). Asociación de Agencias de Turismo del Cusco. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ "Acuerdos interinstitucionales registrados por dependencias y municipios de Puebla". sre.gob.mx (in Spanish). Secretaría de relaciones exteriores. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ "Twinning between the cities of Cusco and San Miguel de Allende is a reality". San Miguel Times. 23 August 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Intercambio cultural entre las ciudades hermanas de Takayama y Cusco". Plataforma del Estado Peruano (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ "Our Sister Cities". tempesistercities.org. Tempe Sister Cities. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

Bibliography

- Chandler, Tertius; Fox, Gerald (1974). 3000 Years of Urban Growth. New York and London: Academic Press. ISBN 9780127851099.

External links

![]() Cusco travel guide from Wikivoyage

Cusco travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Cusco official website

- Old map of Cusco Archived 20 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Historic Cities site