Danish colonization of the Americas

| Part of a series on |

| European colonization of the Americas |

|---|

|

|

|

Denmark and the former real union of Denmark–Norway had a colonial empire from the 17th through to the 20th centuries, large portions of which were found in the Americas. Denmark and Norway in one form or another also maintained land claims in Greenland since the 13th century, the former up through the twenty-first century.

West Indies (1754–1917)

Explorers (mainly Norwegians), scientists, merchants (mainly Danish) and settlers from Denmark–Norway took possession of the Danish West Indies (present-day U.S. Virgin Islands) in the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

Denmark–Norway started colonies on St. Thomas in 1665 and St. John in 1683 (though control of the latter was disputed with Great Britain until 1718), and purchased St. Croix from France in 1733. During the 18th century, the Virgin Islands in the Caribbean Sea were divided into two territorial units, one British and the other Dano-Norwegian. The Dano-Norwegian islands were run by the Danish West India and Guinea Company until 1755, when the Dano-Norwegian king bought them out. Following the Battle of Leipzig in 1813, the Treaty of Kiel signed on 14 January 1814, Frederick VI ceded the Kingdom of Norway to the King of Sweden. Despite Norway then being under the Swedish crown some Norwegians kept coming due to family connections.

Sugar cane, produced by slave labor, drove the islands' economy during the 18th and early 19th centuries. A triangular trade existed with Danish manufacturers buying African slaves which in turn were traded for West Indian sugar meant for Denmark and Norway. Although the slave trade was abolished in 1803, slavery itself was not abolished until 1848, after several mass slave escapes to the free British islands and an ensuing slave protest. The Danish Virgin Islands were also used as a base for pirates. The British and Dutch settlers became the largest non-slave groups on the islands. Their languages predominated, so much so that the Danish government, in 1839, declared that slave children must attend school in the English language. The colony reached its largest population in the 1840–50s, after which an economic downturn increased emigration and the population dropped, a trend that continued until after the islands' purchase by the United States. The Danish West Indies had 34,000 inhabitants in 1880.

In 1868, Denmark voted to sell the colony to the United States but their offer was rebuffed. In 1902, Denmark rejected an American purchase offer. On 31 March 1917, the United States finally purchased the islands, which had been in economic decline since the abolition of slavery.

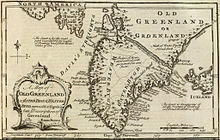

Greenland (1728/1814–present)

Greenland, which had been settled by the Norsemen in the 980s,[1] submitted to Norwegian rule in 1261.[2] Denmark and Sweden entered the Kalmar Union with Norway in 1397 under the Queen of Norway, and Norway's overseas territories including Greenland later became subject to the king in Copenhagen.[3] Scandinavian settlement in Greenland declined over the years and the last written record is a marriage recorded in 1408, although the Norwegian claims to the land remained. Following the establishment of an independent Sweden, Norway and Denmark were reorganized into a polity now known as Denmark–Norway in 1536/1537 and the nominal Norwegian sovereignty over Greenland was taken up by the new union. Despite the decline of European settlement and the loss of contact, Denmark–Norway continued to maintain its claim to lordship over Greenland.

Between the years 1605–1607, King Christian IV of Denmark–Norway commissioned three expeditions to Greenland. These expeditions were conducted in order to locate the lost Norse Eastern Settlement as well as to reassert Danish sovereignty over Greenland. The expeditions were largely unsuccessful, partly due to its leaders lacking experience with the arctic ice and difficult weather conditions. Additionally later expeditions were searching on the east coast of Greenland, which was almost inaccessible at the time due to southward-drifting ice. [4] In the 1660s, a polar bear was added to the royal coat of arms. Around this same time Dano-Norwegian ships, joined by ships from various other European countries, began journeying to Greenland to hunt bowhead whales, though no formal recolonization was attempted.

In 1721, the Norwegian Lutheran minister Hans Egede and his Bergen Greenland Company received a royal charter from King Frederick IV granting them broad authority over Greenland and commissioning them to seek out the old Norse colony and spread the Reformation among its inhabitants, who were presumed to still be Catholic or to have reverted to paganism. Egede led three boats to Baal's River (the modern Nuup Kangerlua) and established Hope Colony on Kangeq with his family and a few dozen colonists. Finding no Norse survivors, he started a mission among the Inuit and baptized the first child converts in 1724. Meanwhile, his settlers had been ravaged by scurvy and the Dutch attacked and burnt a whaling station erected on Nipisat. The Bergen company went bankrupt in 1727. King Frederick attempted to replace it with a royal colony by sending Major Claus Paarss and several dozen soldiers and convicts to erect a fortress for the colony in 1728 but this new settlement of Good Hope (Godthaab) failed due to mutiny[5] and scurvy and the retinue was recalled in 1730.[2]

Three Moravian missionaries led by Matthias Stach arrived in 1733 and began the first of a series of mission stations at Neu-Herrnhut (which later developed into the modern capital Nuuk), but a returning Inuit child brought smallpox from Denmark and a large proportion of the native population died over the next few years. The death of Egede's wife prompted his return to Denmark, with his son Paul left in charge of the settlement. The Danish merchant Jacob Severin was granted authority over the colony from 1734 to 1740, which was extended until 1749, assisted by royal patronage and Moravian sponsorship of some of Egede's missionary activities. He was succeeded by the General Trade Company (Det almindelige Handelskompagni). Both were granted armed ships and full monopolies over trade around their settlements, to prevent better-armed, lower-priced, and better-quality Dutch goods from bankrupting the enterprise.[2] The ranged nature of their monopolies spurred them to found new settlements: Christianshaab (1734), Jakobshavn (1741), Frederikshaab (1742), Claushavn (1752), Fiskenæsset (1754), Ritenbenck and Egedesminde and Sukkertoppen (1755), Holsteinsborg (1756), Umanak (1758), Upernavik (1771), Godhavn (1773), and Julianehaab (1774). The GTC folded in 1774 and was replaced by the Royal Greenland Trade Department (Kongelige Grønlandske Handel, KGH), which recognized that the island possessed neither fertile farmland nor easily accessible mineral wealth and that income would be dependent on the whaling and seal-hunting trade with the native Inuit. An early attempt to man a government-run Scandinavian whaling fleet was aborted and instead the KGH's Instruction of 1782 banned further attempts to urbanize the Inuit or alter their traditional way of life through improved employment opportunities or sales of luxury items.[2] One effect was that construction of new settlements was effectively suspended after Nennortalik (1797) for a century until the establishment of Amassalik on the eastern shore in 1894. The 1782 Instructions also established separate governing councils for North and South Greenland.

Danish intervention on France's behalf during the Napoleonic Wars ended with the severing of Denmark–Norway under the 1814 Treaty of Kiel, which granted mainland Norway to Sweden but retained the former Norwegian colonies under the Danish crown. Repeated inquiries into the Greenlandic trade and the end of absolutism in Denmark did not end the KGH's monopolies.[2] In 1857, the administrators did set up parsissaets, local councils conducted in Kalaallisut with minor control over spending decisions at each station. In 1912, Royal Greenland's independence was ended and its operations were folded into the Ministry of the Interior.

Arctic exploration placed claims of Danish sovereignty over the whole of Greenland in doubt: the principle of terra nullius seemed to leave huge tracts of the territory available to new entrants. Denmark responded by acquiring diplomatic agreements recognizing its sovereignty from the parties involved, beginning with the treaty selling the Danish Virgin Islands to the United States in 1917.[6] Norway – which had become independent of Sweden in 1905 – eventually protested and claimed Erik the Red's Land in eastern Greenland during 1931. The Permanent Court of International Justice ruled against Norway and supported the Danish sovereignty two years later.

The invasion of Denmark in early 1940 increased the power and importance of the governors greatly, but by 1941 the island had become an American protectorate. Following the war, the former corporate policy was discontinued: the North and South Greenland colonies were united and the RGTD's monopoly officially ended.[7] In 1953, Greenland's colonial status was ended and it was made an integral part of the Kingdom of Denmark with representation in the Folketing. In 1979, the Folketing granted the island home rule and, in 2009, all matters other than defense and foreign policy were transferred to the regional parliament.

See also

- History of Denmark

- History of Greenland

- History of Norway

- Virgin Islands National Park

- Danish people in Greenland

References

- ^ The Fate of Greenland's Vikings, by Dale Mackenzie Brown, Archaeological Institute of America, February 28, 2000

- ^ a b c d e Marquardt, Ole. "Change and Continuity in Denmark's Greenland Policy" in The Oldenburg Monarchy: An Underestimated Empire?. Verlag Ludwig (Kiel), 2006.

- ^ Boraas, Tracey (2002). Sweden. Capstone Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-7368-0939-2.

- ^ Gosch, C.C.A. Danish Arctic Expeditions, 1605 to 1620. Book I.—The Danish Expeditions to Greenland in 1605, 1606, and 1607; to which is added Captain James Hall's Voyage to Greenland in 1612 London: Hakluyt Society. 1897

- ^ Cranz, David & al. The History of Greenland: including an account of the mission carried on by the United Brethren in that country. Longman, 1820.

- ^ Cavell, Janice. "Historical Evidence and the Eastern Greenland Case Archived 2020-07-29 at the Wayback Machine". Arctic, Vol. 61, No. 4 (Dec. 2008), pp. 433–441.

- ^ Royal Greenland. "Our History Archived 2012-05-26 at the Wayback Machine". Accessed 30 Apr 2012.