Fly

| Fly Temporal range: Middle Triassic – Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Diptera from different families:

Housefly (Muscidae) (top left)

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Superorder: | Panorpida |

| (unranked): | Antliophora |

| Order: | Diptera Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Suborders | |

Flies are insects of the order Diptera, the name being derived from the Greek δι- di- "two", and πτερόν pteron "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwings having evolved into advanced mechanosensory organs known as halteres, which act as high-speed sensors of rotational movement and allow dipterans to perform advanced aerobatics. Diptera is a large order containing more than 150,000 species including horse-flies,[a] crane flies, hoverflies, mosquitoes and others.

Flies have a mobile head, with a pair of large compound eyes, and mouthparts designed for piercing and sucking (mosquitoes, black flies and robber flies), or for lapping and sucking in the other groups. Their wing arrangement gives them great manoeuvrability in flight, and claws and pads on their feet enable them to cling to smooth surfaces. Flies undergo complete metamorphosis; the eggs are often laid on the larval food-source and the larvae, which lack true limbs, develop in a protected environment, often inside their food source. Other species are ovoviviparous, opportunistically depositing hatched or hatching larvae instead of eggs on carrion, dung, decaying material, or open wounds of mammals. The pupa is a tough capsule from which the adult emerges when ready to do so; flies mostly have short lives as adults.

Diptera is one of the major insect orders and of considerable ecological and human importance. Flies are major pollinators, second only to the bees and their Hymenopteran relatives. Flies may have been among the evolutionarily earliest pollinators responsible for early plant pollination. Fruit flies are used as model organisms in research, but less benignly, mosquitoes are vectors for malaria, dengue, West Nile fever, yellow fever, encephalitis, and other infectious diseases; and houseflies, commensal with humans all over the world, spread foodborne illnesses. Flies can be annoyances especially in some parts of the world where they can occur in large numbers, buzzing and settling on the skin or eyes to bite or seek fluids. Larger flies such as tsetse flies and screwworms cause significant economic harm to cattle. Blowfly larvae, known as gentles, and other dipteran larvae, known more generally as maggots, are used as fishing bait, as food for carnivorous animals, and in medicine in debridement, to clean wounds.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

Relationships to other insects

Dipterans are holometabolans, insects that undergo radical metamorphosis. They belong to the Mecopterida, alongside the Mecoptera, Siphonaptera, Lepidoptera and Trichoptera.[3][4] The possession of a single pair of wings distinguishes most true flies from other insects with "fly" in their names. However, some true flies such as Hippoboscidae (louse flies) have become secondarily wingless.[5][6]

The cladogram represents the current consensus view.[7]

| Holometabola |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Relationships between subgroups and families

The first true dipterans known are from the Middle Triassic (around 240 million years ago), and they became widespread during the Middle and Late Triassic.[8] Modern flowering plants did not appear until the Cretaceous (around 140 million years ago), so the original dipterans must have had a different source of nutrition other than nectar. Based on the attraction of many modern fly groups to shiny droplets, it has been suggested that they may have fed on honeydew produced by sap-sucking bugs which were abundant at the time, and dipteran mouthparts are well-adapted to softening and lapping up the crusted residues.[9] The basal clades in the Diptera include the Deuterophlebiidae and the enigmatic Nymphomyiidae.[10] Three episodes of evolutionary radiation are thought to have occurred based on the fossil record. Many new species of lower Diptera developed in the Triassic, about 220 million years ago. Many lower Brachycera appeared in the Jurassic, some 180 million years ago. A third radiation took place among the Schizophora at the start of the Paleogene, 66 million years ago.[10]

The phylogenetic position of Diptera has been controversial. The monophyly of holometabolous insects has long been accepted, with the main orders being established as Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, Hymenoptera and Diptera, and it is the relationships between these groups which has caused difficulties. Diptera is widely thought to be a member of Mecopterida, along with Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), Trichoptera (caddisflies), Siphonaptera (fleas), Mecoptera (scorpionflies) and possibly Strepsiptera (twisted-wing flies). Diptera has been grouped with Siphonaptera and Mecoptera in the Antliophora, but this has not been confirmed by molecular studies.[11]

Diptera were traditionally broken down into two suborders, Nematocera and Brachycera, distinguished by the differences in antennae. The Nematocera are identified by their elongated bodies and many-segmented, often feathery antennae as represented by mosquitoes and crane flies. The Brachycera have rounder bodies and much shorter antennae.[12][13] Subsequent studies have identified the Nematocera as being non-monophyletic with modern phylogenies placing the Brachycera within grades of groups formerly placed in the Nematocera. The construction of a phylogenetic tree has been the subject of ongoing research. The following cladogram is based on the FLYTREE project.[14][15]

| Diptera |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Cal=Calyptratae

- Cyc=Cyclorrhapha

- Ere=Eremoneura

- Mus=Muscomorpha

- Sch=Schizophora

Diversity

Flies are often abundant and are found in almost all terrestrial habitats in the world apart from Antarctica. They include many familiar insects such as house flies, blow flies, mosquitoes, gnats, black flies, midges and fruit flies. More than 150,000 have been formally described and the actual species diversity is much greater, with the flies from many parts of the world yet to be studied intensively.[16][17] The suborder Nematocera include generally small, slender insects with long antennae such as mosquitoes, gnats, midges and crane-flies, while the Brachycera includes broader, more robust flies with short antennae. Many nematoceran larvae are aquatic.[18] There are estimated to be a total of about 19,000 species of Diptera in Europe, 22,000 in the Nearctic region, 20,000 in the Afrotropical region, 23,000 in the Oriental region and 19,000 in the Australasian region.[19] While most species have restricted distributions, a few like the housefly (Musca domestica) are cosmopolitan.[20] Gauromydas heros (Asiloidea), with a length of up to 7 cm (2.8 in), is generally considered to be the largest fly in the world,[21] while the smallest is Euryplatea nanaknihali, which at 0.4 mm (0.016 in) is smaller than a grain of salt.[22]

Brachycera are ecologically very diverse, with many being predatory at the larval stage and some being parasitic. Animals parasitised include molluscs, woodlice, millipedes, insects, mammals,[19] and amphibians.[23] Flies are the second largest group of pollinators after the Hymenoptera (bees, wasps and relatives). In wet and colder environments flies are significantly more important as pollinators. Compared to bees, they need less food as they do not need to provision their young. Many flowers that bear low nectar and those that have evolved trap pollination depend on flies.[24] It is thought that some of the earliest pollinators of plants may have been flies.[25]

The greatest diversity of gall forming insects are found among the flies, principally in the family Cecidomyiidae (gall midges).[26] Many flies (most importantly in the family Agromyzidae) lay their eggs in the mesophyll tissue of leaves with larvae feeding between the surfaces forming blisters and mines.[27] Some families are mycophagous or fungus feeding. These include the cave dwelling Mycetophilidae (fungus gnats) whose larvae are the only diptera with bioluminescence. The Sciaridae are also fungus feeders. Some plants are pollinated by fungus feeding flies that visit fungus infected male flowers.[28]

The larvae of Megaselia scalaris (Phoridae) are almost omnivorous and consume such substances as paint and shoe polish.[29] The Exorista mella (Walker) fly are considered generalists and parasitoids of a variety of hosts.[30] The larvae of the shore flies (Ephydridae) and some Chironomidae survive in extreme environments including glaciers (Diamesa sp., Chironomidae[31]), hot springs, geysers, saline pools, sulphur pools, septic tanks and even crude oil (Helaeomyia petrolei[31]).[19] Adult hoverflies (Syrphidae) are well known for their mimicry and the larvae adopt diverse lifestyles including being inquiline scavengers inside the nests of social insects.[32] Some brachycerans are agricultural pests, some bite animals and humans and suck their blood, and some transmit diseases.[19]

Anatomy and morphology

Flies are adapted for aerial movement and typically have short and streamlined bodies. The first tagma of the fly, the head, bears the eyes, the antennae, and the mouthparts (the labrum, labium, mandible, and maxilla make up the mouthparts). The second tagma, the thorax, bears the wings and contains the flight muscles on the second segment, which is greatly enlarged; the first and third segments have been reduced to collar-like structures, and the third segment bears the halteres, which help to balance the insect during flight. The third tagma is the abdomen consisting of 11 segments, some of which may be fused, and with the three hindmost segments modified for reproduction.[33][34] Some Dipterans are mimics and can only be distinguished from their models by very careful inspection. An example of this is Spilomyia longicornis, which is a fly but mimics a vespid wasp.

Flies have a mobile head with a pair of large compound eyes on the sides of the head, and in most species, three small ocelli on the top. The compound eyes may be close together or widely separated, and in some instances are divided into a dorsal region and a ventral region, perhaps to assist in swarming behaviour. The antennae are well-developed but variable, being thread-like, feathery or comb-like in the different families. The mouthparts are adapted for piercing and sucking, as in the black flies, mosquitoes and robber flies, and for lapping and sucking as in many other groups.[34] Female horse-flies use knife-like mandibles and maxillae to make a cross-shaped incision in the host's skin and then lap up the blood that flows. The gut includes large diverticulae, allowing the insect to store small quantities of liquid after a meal.[35]

For visual course control, flies' optic flow field is analyzed by a set of motion-sensitive neurons.[36] A subset of these neurons is thought to be involved in using the optic flow to estimate the parameters of self-motion, such as yaw, roll, and sideward translation.[37] Other neurons are thought to be involved in analyzing the content of the visual scene itself, such as separating figures from the ground using motion parallax.[38][39] The H1 neuron is responsible for detecting horizontal motion across the entire visual field of the fly, allowing the fly to generate and guide stabilizing motor corrections midflight with respect to yaw.[40] The ocelli are concerned in the detection of changes in light intensity, enabling the fly to react swiftly to the approach of an object.[41]

Like other insects, flies have chemoreceptors that detect smell and taste, and mechanoreceptors that respond to touch. The third segments of the antennae and the maxillary palps bear the main olfactory receptors, while the gustatory receptors are in the labium, pharynx, feet, wing margins and female genitalia,[42] enabling flies to taste their food by walking on it. The taste receptors in females at the tip of the abdomen receive information on the suitability of a site for ovipositing.[41] Flies that feed on blood have special sensory structures that can detect infrared emissions, and use them to home in on their hosts. Many blood-sucking flies can detect the raised concentration of carbon dioxide that occurs near large animals.[43] Some tachinid flies (Ormiinae) which are parasitoids of bush crickets, have sound receptors to help them locate their singing hosts.[44]

Diptera have one pair of fore wings on the mesothorax and a pair of halteres, or reduced hind wings, on the metathorax. A further adaptation for flight is the reduction in number of the neural ganglia, and concentration of nerve tissue in the thorax, a feature that is most extreme in the highly derived Muscomorpha infraorder.[35] Some flies such as the ectoparasitic Nycteribiidae and Streblidae are exceptional in having lost their wings and become flightless. The only other order of insects bearing a single pair of true, functional wings, in addition to any form of halteres, are the Strepsiptera. In contrast to the flies, the Strepsiptera bear their halteres on the mesothorax and their flight wings on the metathorax.[45] Each of the fly's six legs has a typical insect structure of coxa, trochanter, femur, tibia and tarsus, with the tarsus in most instances being subdivided into five tarsomeres.[34] At the tip of the limb is a pair of claws, and between these are cushion-like structures known as pulvilli which provide adhesion.[46]

The abdomen shows considerable variability among members of the order. It consists of eleven segments in primitive groups and ten segments in more derived groups, the tenth and eleventh segments having fused.[47] The last two or three segments are adapted for reproduction. Each segment is made up of a dorsal and a ventral sclerite, connected by an elastic membrane. In some females, the sclerites are rolled into a flexible, telescopic ovipositor.[34]

Flight

Flies are capable of great manoeuvrability during flight due to the presence of the halteres. These act as gyroscopic organs and are rapidly oscillated in time with the wings; they act as a balance and guidance system by providing rapid feedback to the wing-steering muscles, and flies deprived of their halteres are unable to fly. The wings and halteres move in synchrony but the amplitude of each wing beat is independent, allowing the fly to turn sideways.[48] The wings of the fly are attached to two kinds of muscles, those used to power it and another set used for fine control.[49]

Flies tend to fly in a straight line then make a rapid change in direction before continuing on a different straight path. The directional changes are called saccades and typically involve an angle of 90°, being achieved in 50 milliseconds. They are initiated by visual stimuli as the fly observes an object, nerves then activate steering muscles in the thorax that cause a small change in wing stroke which generate sufficient torque to turn. Detecting this within four or five wingbeats, the halteres trigger a counter-turn and the fly heads off in a new direction.[50]

Flies have rapid reflexes that aid their escape from predators but their sustained flight speeds are low. Dolichopodid flies in the genus Condylostylus respond in less than five milliseconds to camera flashes by taking flight.[51] In the past, the deer bot fly, Cephenemyia, was claimed to be one of the fastest insects on the basis of an estimate made visually by Charles Townsend in 1927.[52] This claim, of speeds of 600 to 800 miles per hour, was regularly repeated until it was shown to be physically impossible as well as incorrect by Irving Langmuir. Langmuir suggested an estimated speed of 25 miles per hour.[53][54][55]

Although most flies live and fly close to the ground, a few are known to fly at heights and a few like Oscinella (Chloropidae) are known to be dispersed by winds at altitudes of up to 2,000 ft and over long distances.[56] Some hover flies like Metasyrphus corollae have been known to undertake long flights in response to aphid population spurts.[57]

Males of fly species such as Cuterebra, many hover flies,[58] bee flies (Bombyliidae)[59] and fruit flies (Tephritidae)[60] maintain territories within which they engage in aerial pursuit to drive away intruding males and other species.[61] While these territories may be held by individual males, some species, such as A. freeborni,[62] form leks with many males aggregating in displays.[60] Some flies maintain an airspace and still others form dense swarms that maintain a stationary location with respect to landmarks. Many flies mate in flight while swarming.[63]

Life cycle and development

Diptera go through a complete metamorphosis with four distinct life stages – egg, larva, pupa and adult.

Larva

In many flies, the larval stage is long and adults may have a short life. Most dipteran larvae develop in protected environments; many are aquatic and others are found in moist places such as carrion, fruit, vegetable matter, fungi and, in the case of parasitic species, inside their hosts. They tend to have thin cuticles and become desiccated if exposed to the air. Apart from the Brachycera, most dipteran larvae have sclerotised head capsules, which may be reduced to remnant mouth hooks; the Brachycera, however, have soft, gelatinized head capsules from which the sclerites are reduced or missing. Many of these larvae retract their heads into their thorax.[34][64] The spiracles in the larva and pupa do not have any internal mechanical closing device.[65]

Some other anatomical distinction exists between the larvae of the Nematocera and the Brachycera. Especially in the Brachycera, little demarcation is seen between the thorax and abdomen, though the demarcation may be visible in many Nematocera, such as mosquitoes; in the Brachycera, the head of the larva is not clearly distinguishable from the rest of the body, and few, if any, sclerites are present. Informally, such brachyceran larvae are called maggots,[66] but the term is not technical and often applied indifferently to fly larvae or insect larvae in general. The eyes and antennae of brachyceran larvae are reduced or absent, and the abdomen also lacks appendages such as cerci. This lack of features is an adaptation to food such as carrion, decaying detritus, or host tissues surrounding endoparasites.[35] Nematoceran larvae generally have well-developed eyes and antennae, while those of Brachyceran larvae are reduced or modified.[67]

Dipteran larvae have no jointed, "true legs",[64] but some dipteran larvae, such as species of Simuliidae, Tabanidae and Vermileonidae, have prolegs adapted to hold onto a substrate in flowing water, host tissues or prey.[68] The majority of dipterans are oviparous and lay batches of eggs, but some species are ovoviviparous, where the larvae starting development inside the eggs before they hatch or viviparous, the larvae hatching and maturing in the body of the mother before being externally deposited. These are found especially in groups that have larvae dependent on food sources that are short-lived or are accessible for brief periods.[69] This is widespread in some families such as the Sarcophagidae. In Hylemya strigosa (Anthomyiidae) the larva moults to the second instar before hatching, and in Termitoxenia (Phoridae) females have incubation pouches, and a full developed third instar larva is deposited by the adult and it almost immediately pupates with no freely feeding larval stage. The tsetse fly (as well as other Glossinidae, Hippoboscidae, Nycteribidae and Streblidae) exhibits adenotrophic viviparity; a single fertilised egg is retained in the oviduct and the developing larva feeds on glandular secretions. When fully grown, the female finds a spot with soft soil and the larva works its way out of the oviduct, buries itself and pupates. Some flies like Lundstroemia parthenogenetica (Chironomidae) reproduce by thelytokous parthenogenesis, and some gall midges have larvae that can produce eggs (paedogenesis).[70][71]

Pupa

The pupae take various forms. In some groups, particularly the Nematocera, the pupa is intermediate between the larval and adult form; these pupae are described as "obtect", having the future appendages visible as structures that adhere to the pupal body. The outer surface of the pupa may be leathery and bear spines, respiratory features or locomotory paddles. In other groups, described as "coarctate", the appendages are not visible. In these, the outer surface is a puparium, formed from the last larval skin, and the actual pupa is concealed within. When the adult insect is ready to emerge from this tough, desiccation-resistant capsule, it inflates a balloon-like structure on its head, and forces its way out.[34]

Adult

The adult stage is usually short, its function is only to mate and lay eggs. The genitalia of male flies are rotated to a varying degree from the position found in other insects.[72] In some flies, this is a temporary rotation during mating, but in others, it is a permanent torsion of the organs that occurs during the pupal stage. This torsion may lead to the anus being below the genitals, or, in the case of 360° torsion, to the sperm duct being wrapped around the gut and the external organs being in their usual position. When flies mate, the male initially flies on top of the female, facing in the same direction, but then turns around to face in the opposite direction. This forces the male to lie on his back for his genitalia to remain engaged with those of the female, or the torsion of the male genitals allows the male to mate while remaining upright. This leads to flies having more reproduction abilities than most insects, and much quicker. Flies occur in large populations due to their ability to mate effectively and quickly during the mating season.[35] More primitive groups mates in the air during swarming, but most of the more advanced species with a 360° torsion mate on a substrate.[73]

Ecology

As ubiquitous insects, dipterans play an important role at various trophic levels both as consumers and as prey. In some groups the larvae complete their development without feeding, and in others the adults do not feed. The larvae can be herbivores, scavengers, decomposers, predators or parasites, with the consumption of decaying organic matter being one of the most prevalent feeding behaviours. The fruit or detritus is consumed along with the associated micro-organisms, a sieve-like filter in the pharynx being used to concentrate the particles, while flesh-eating larvae have mouth-hooks to help shred their food. The larvae of some groups feed on or in the living tissues of plants and fungi, and some of these are serious pests of agricultural crops. Some aquatic larvae consume the films of algae that form underwater on rocks and plants. Many of the parasitoid larvae grow inside and eventually kill other arthropods, while parasitic larvae may attack vertebrate hosts.[34]

Whereas many dipteran larvae are aquatic or live in enclosed terrestrial locations, the majority of adults live above ground and are capable of flight. Predominantly they feed on nectar or plant or animal exudates, such as honeydew, for which their lapping mouthparts are adapted. Some flies have functional mandibles that may be used for biting. The flies that feed on vertebrate blood have sharp stylets that pierce the skin, with some species having anticoagulant saliva that is regurgitated before absorbing the blood that flows; in this process, certain diseases can be transmitted. The bot flies (Oestridae) have evolved to parasitize mammals. Many species complete their life cycle inside the bodies of their hosts.[74] The larvae of a few fly groups (Agromyzidae, Anthomyiidae, Cecidomyiidae) are capable of inducing plant galls. Some dipteran larvae are leaf-miners. The larvae of many brachyceran families are predaceous. In many dipteran groups, swarming is a feature of adult life, with clouds of insects gathering in certain locations; these insects are mostly males, and the swarm may serve the purpose of making their location more visible to females.[34]

Most adult diptera have their mouthparts modified to sponge up fluid. The adults of many species of flies (e.g. Anthomyia sp., Steganopsis melanogaster) that feed on liquid food will regurgitate fluid in a behaviour termed as "bubbling" which has been thought to help the insects evaporate water and concentrate food[75] or possibly to cool by evaporation.[76] Some adult diptera are known for kleptoparasitism such as members of the Sarcophagidae. The miltogramminae are known as "satellite flies" for their habit of following wasps and stealing their stung prey or laying their eggs into them. Phorids, milichids and the genus Bengalia are known to steal food carried by ants.[77] Adults of Ephydra hians forage underwater, and have special hydrophobic hairs that trap a bubble of air that lets them breathe underwater.[78]

Anti-predator adaptations

Flies are eaten by other animals at all stages of their development. The eggs and larvae are parasitised by other insects and are eaten by many creatures, some of which specialise in feeding on flies but most of which consume them as part of a mixed diet. Birds, bats, frogs, lizards, dragonflies and spiders are among the predators of flies.[79] Many flies have evolved mimetic resemblances that aid their protection. Batesian mimicry is widespread with many hoverflies resembling bees and wasps,[80][81] ants[82] and some species of tephritid fruit fly resembling spiders.[83] Some species of hoverfly are myrmecophilous—their young live and grow within the nests of ants. They are protected from the ants by imitating chemical odours given by ant colony members.[84] Bombyliid bee flies such as Bombylius major are short-bodied, round, furry, and distinctly bee-like as they visit flowers for nectar, and are likely also Batesian mimics of bees.[85]

In contrast, Drosophila subobscura, a species of fly in the genus Drosophila, lacks a category of hemocytes that are present in other studied species of Drosophila, leading to an inability to defend against parasitic attacks, a form of innate immunodeficiency.[86]

Human interaction and cultural depictions

Symbolism

Flies play a variety of symbolic roles in different cultures. These include both positive and negative roles in religion. In the traditional Navajo religion, Big Fly is an important spirit being.[87][88][89] In Christian demonology, Beelzebub is a demonic fly, the "Lord of the Flies", and a god of the Philistines.[90][91][92]

Flies have appeared in literature since ancient Sumer.[93] In a Sumerian poem, a fly helps the goddess Inanna when her husband Dumuzid is being chased by galla demons.[93] In the Mesopotamian versions of the flood myth, the dead corpses floating on the waters are compared to flies.[93] Later, the gods are said to swarm "like flies" around the hero Utnapishtim's offering.[93] Flies appear on Old Babylonian seals as symbols of Nergal, the god of death.[93] Fly-shaped lapis lazuli beads were often worn in ancient Mesopotamia, along with other kinds of fly-jewellery.[93]

In Ancient Egypt, flies appear in amulets and as a military award for bravery and tenacity, due to the fact that they always come back when swatted at. It is thought that flies may have also been associated with the departing spirit of the dead, as they are often found near dead bodies. In modern Egypt, a similar belief persists in some areas to not swat at shiny green flies, as they may be carrying the soul of a recently deceased person.[94]

In a little-known Greek myth, a very chatty and talkative maiden named Myia (meaning "fly") enraged the moon-goddess Selene by attempting to seduce her lover, the sleeping Endymion, and was thus turned by the angry goddess into a fly, who now always deprives people of their sleep in memory of her past life.[95][96] In Prometheus Bound, which is attributed to the Athenian tragic playwright Aeschylus, a gadfly sent by Zeus's wife Hera pursues and torments his mistress Io, who has been transformed into a cow and is watched constantly by the hundred eyes of the herdsman Argus:[97][98] "Io: Ah! Hah! Again the prick, the stab of gadfly-sting! O earth, earth, hide, the hollow shape—Argus—that evil thing—the hundred-eyed."[98] William Shakespeare, inspired by Aeschylus, has Tom o'Bedlam in King Lear, "Whom the foul fiend hath led through fire and through flame, through ford and whirlpool, o'er bog and quagmire", driven mad by the constant pursuit.[98] In Antony and Cleopatra, Shakespeare similarly likens Cleopatra's hasty departure from the Actium battlefield to that of a cow chased by a gadfly.[99] More recently, in 1962 the biologist Vincent Dethier wrote To Know a Fly, introducing the general reader to the behaviour and physiology of the fly.[100]

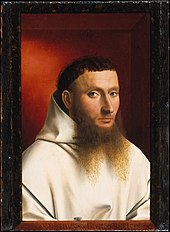

Musca depicta ("painted fly" in Latin) is a depiction of a fly as an inconspicuous element of various paintings. This feature was widespread in 15th and 16th centuries paintings and its presence may be explained by various reasons.[101]

Flies appear in popular culture in concepts such as fly-on-the-wall documentary-making in film and television production. The metaphoric name suggests that events are seen candidly, as a fly might see them.[102] Flies have inspired the design of miniature flying robots.[103] Steven Spielberg's 1993 film Jurassic Park relied on the idea that DNA could be preserved in the stomach contents of a blood-sucking fly fossilised in amber, though the mechanism has been discounted by scientists.[104]

Economic importance

Dipterans are an important group of insects and have a considerable impact on the environment. Some leaf-miner flies (Agromyzidae), fruit flies (Tephritidae and Drosophilidae) and gall midges (Cecidomyiidae) are pests of agricultural crops; others such as tsetse flies, screwworm and botflies (Oestridae) attack livestock, causing wounds, spreading disease, and creating significant economic harm. See article: Parasitic flies of domestic animals. A few can even cause myiasis in humans. Still others such as mosquitoes (Culicidae), blackflies (Simuliidae) and drain flies (Psychodidae) impact human health, acting as vectors of major tropical diseases. Among these, Anopheles mosquitoes transmit malaria, filariasis, and arboviruses; Aedes aegypti mosquitoes carry dengue fever and the Zika virus; blackflies carry river blindness; sand flies carry leishmaniasis. Other dipterans are a nuisance to humans, especially when present in large numbers; these include houseflies, which contaminate food and spread food-borne illnesses; the biting midges and sandflies (Ceratopogonidae) and the houseflies and stable flies (Muscidae).[34] In tropical regions, eye flies (Chloropidae) which visit the eye in search of fluids can be a nuisance in some seasons.[105]

Many dipterans serve roles that are useful to humans. Houseflies, blowflies and fungus gnats (Mycetophilidae) are scavengers and aid in decomposition. Robber flies (Asilidae), tachinids (Tachinidae) and dagger flies and balloon flies (Empididae) are predators and parasitoids of other insects, helping to control a variety of pests. Many dipterans such as bee flies (Bombyliidae) and hoverflies (Syrphidae) are pollinators of crop plants.[34]

Uses

Drosophila melanogaster, a fruit fly, has long been used as a model organism in research because of the ease with which it can be bred and reared in the laboratory, its small genome, and the fact that many of its genes have counterparts in higher eukaryotes. A large number of genetic studies have been undertaken based on this species; these have had a profound impact on the study of gene expression, gene regulatory mechanisms and mutation. Other studies have investigated physiology, microbial pathogenesis and development among other research topics.[106] The studies on dipteran relationships by Willi Hennig helped in the development of cladistics, techniques that he applied to morphological characters but now adapted for use with molecular sequences in phylogenetics.[107]

Maggots found on corpses are useful to forensic entomologists. Maggot species can be identified by their anatomical features and by matching their DNA. Maggots of different species of flies visit corpses and carcases at fairly well-defined times after the death of the victim, and so do their predators, such as beetles in the family Histeridae. Thus, the presence or absence of particular species provides evidence for the time since death, and sometimes other details such as the place of death, when species are confined to particular habitats such as woodland.[108]

Some species of maggots such as blowfly larvae (gentles) and bluebottle larvae (casters) are bred commercially; they are sold as bait in angling, and as food for carnivorous animals (kept as pets, in zoos, or for research) such as some mammals,[109] fishes, reptiles, and birds. It has been suggested that fly larvae could be used at a large scale as food for farmed chickens, pigs, and fish. However, consumers are opposed to the inclusion of insects in their food, and the use of insects in animal feed remains illegal in areas such as the European Union.[110][111]

Fly larvae can be used as a biomedical tool for wound care and treatment. Maggot debridement therapy (MDT) is the use of blow fly larvae to remove the dead tissue from wounds, most commonly being amputations. Historically, this has been used for centuries, both intentional and unintentional, on battlefields and in early hospital settings.[112] Removing the dead tissue promotes cell growth and healthy wound healing. The larvae also have biochemical properties such as antibacterial activity found in their secretions as they feed.[113] These medicinal maggots are a safe and effective treatment for chronic wounds.[114]

The Sardinian cheese casu marzu is exposed to flies known as cheese skippers such as Piophila casei, members of the family Piophilidae.[115] The digestive activities of the fly larvae soften the cheese and modify the aroma as part of the process of maturation. At one time European Union authorities banned sale of the cheese and it was becoming hard to find,[116] but the ban has been lifted on the grounds that the cheese is a traditional local product made by traditional methods.[117]

Hazards

Flies are a health hazard and are attracted to toilets because of their smell. The New Scientist magazine suggested a trap for these flies. A pipe acting as a chimney was fitted to the toilet which let in some light to attract these flies up to the end of this pipe where a gauze covering prevented escape to the air outside so that they were trapped and died. Toilets are generally dark inside particularly if the door is closed.

Notes

- ^ Some authors draw a distinction in writing the common names of insects. True flies are in their view best written as two words, such as crane fly, robber fly, bee fly, moth fly, and fruit fly. In contrast, common names of non-dipteran insects that have "fly" in their names are written as one word, e.g. butterfly, stonefly, dragonfly, scorpionfly, sawfly, caddisfly, whitefly.[1] In practice, however, this is a comparatively new convention; especially in older books, names like "saw fly" and "caddis fly", or hyphenated forms such as house-fly and dragon-fly are widely used.[2] Exceptions to this rule occur, such as the hoverfly, which is a true fly, and the Spanish fly, a type of blister beetle.

References

- ^ "Order Diptera: Flies". BugGuide. Iowa State University. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ^ Comstock, John Henry (1949). An Introduction to Entomology. Comstock Publishing. p. 773.

- ^ Peters, Ralph S.; Meusemann, Karen; Petersen, Malte; Mayer, Christoph; Wilbrandt, Jeanne; Ziesmann, Tanja; et al. (2014). "The evolutionary history of holometabolous insects inferred from transcriptome-based phylogeny and comprehensive morphological data". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 14 (1): 52. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-14-52. PMC 4000048. PMID 24646345.

- ^ "Taxon: Superorder Antliophora". The Taxonomicon. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- ^ Hutson, A. M. (1984). Diptera: Keds, flat-flies & bat-flies (Hippoboscidae & Nycteribiidae). Handbooks for the Identification of British Insects. Vol. 10 pt 7. Royal Entomological Society of London. p. 84.

- ^ Mayhew, Peter J. (2007). "Why are there so many insect species? Perspectives from fossils and phylogenies". Biological Reviews. 82 (3): 425–454. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00018.x. PMID 17624962. S2CID 9356614.

- ^ Kjer, Karl M.; Simon, Chris; Yavorskaya, Margarita & Beutel, Rolf G. (2016). "Progress, pitfalls and parallel universes: a history of insect phylogenetics". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 13 (121): 121. doi:10.1098/rsif.2016.0363. PMC 5014063. PMID 27558853.

- ^ Blagoderov, V. A.; Lukashevich, E. D.; Mostovski, M. B. (2002). "Order Diptera Linné, 1758. The true flies". In Rasnitsyn, A. P.; Quicke, D. L. J. (eds.). History of Insects. Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4020-0026-3.

- ^ Downes, William L. Jr.; Dahlem, Gregory A. (1987). "Keys to the Evolution of Diptera: Role of Homoptera". Environmental Entomology. 16 (4): 847–854. doi:10.1093/ee/16.4.847.

- ^ a b Wiegmann, B. M.; Trautwein, M. D.; Winkler, I. S.; Barr, N. B.; Kim, J.-W.; Lambkin, C.; et al. (2011). "Episodic radiations in the fly tree of life". PNAS. 108 (14): 5690–5695. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.5690W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1012675108. PMC 3078341. PMID 21402926.

- ^ Wiegmann, Brian; Yeates, David K. (2012). The Evolutionary Biology of Flies. Columbia University Press. pp. 4–6. ISBN 978-0-231-50170-5.

- ^ B.B. Rohdendorf. 1964. Trans. Inst. Paleont., Acad. Sci. USSR, Moscow, v. 100

- ^ Wiegmann, Brian M.; Yeates, David K. (29 November 2007). "Diptera True Flies". Tree of Life. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ Yeates, David K.; Meier, Rudolf; Wiegmann, Brian. "Phylogeny of True Flies (Diptera): A 250 Million Year Old Success Story in Terrestrial Diversification". Flytree. Illinois Natural History Survey. Archived from the original on 28 December 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ Yeates, David K.; Weigmann, Brian M; Courtney, Greg W.; Meier, Rudolf; Lambkins, Christine; Pape, Thomas (2007). "Phylogeny and systematics of Diptera: Two decades of progress and prospects". Zootaxa. 1668: 565–590. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1668.1.27.

- ^ Pape, Thomas; Bickel, Daniel John; Meier, Rudolf (2009). Diptera Diversity: Status, Challenges and Tools. Brill. p. 13. ISBN 978-90-04-14897-0.

- ^ Yeates, D. K.; Wiegmann, B. M. (1999). "Congruence and controversy: toward a higher-level phylogeny of diptera". Annual Review of Entomology. 44: 397–428. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.44.1.397. PMID 15012378.

- ^ Wiegmann, Brian M.; Yeates, David K. (2007). "Diptera: True flies". Tree of Life Web Project. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d Pape, Thomas; Beuk, Paul; Pont, Adrian Charles; Shatalkin, Anatole I.; Ozerov, Andrey L.; et al. (2015). "Fauna Europaea: Diptera – Brachycera". Biodiversity Data Journal. 3 (3): e4187. doi:10.3897/BDJ.3.e4187. PMC 4339814. PMID 25733962.

- ^ Marquez, J. G.; Krafsur, E. S. (1 July 2002). "Gene Flow Among Geographically Diverse Housefly Populations (Musca domestica L.): A Worldwide Survey of Mitochondrial Diversity". Journal of Heredity. 93 (4): 254–259. doi:10.1093/jhered/93.4.254. PMID 12407211.

- ^ Owen, James (10 December 2015). "World's Biggest Fly Faces Two New Challengers". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 13 December 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Welsh, Jennifer (2 July 2012). "World's Tiniest Fly May Decapitate Ants, Live in Their Heads". Livescience. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Strijbosch, H. (1980). "Mortality in a population of Bufo bufo resulting from the fly Lucilia bufonivora". Oecologia. 45 (2): 285–286. Bibcode:1980Oecol..45..285S. doi:10.1007/BF00346472. PMID 28309542. S2CID 32817424.

- ^ Ssymank, Axel; Kearns, C. A.; Pape, Thomas; Thompson, F. Christian (1 April 2008). "Pollinating Flies (Diptera): A major contribution to plant diversity and agricultural production". Biodiversity. 9 (1–2): 86–89. doi:10.1080/14888386.2008.9712892. S2CID 39619017.

- ^ Labandeira, Conrad C. (3 April 1998). "How Old Is the Flower and the Fly?". Science. 280 (5360): 57–59. doi:10.1126/science.280.5360.57. hdl:10088/5966. S2CID 19305979.

- ^ Price, Peter W. (2005). "Adaptive radiation of gall-inducing insects". Basic and Applied Ecology. 6 (5): 413–421. doi:10.1016/j.baae.2005.07.002.

- ^ Scheffer, Sonja J.; Winkler, Isaac S.; Wiegmann, Brian M. (2007). "Phylogenetic relationships within the leaf-mining flies (Diptera: Agromyzidae) inferred from sequence data from multiple genes". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 42 (3): 756–75. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.12.018. PMID 17291785.

- ^ Sakai, Shoko; Kato, Makoto; Nagamasu, Hidetoshi (2000). "Artocarpus (Moraceae)-Gall Midge Pollination Mutualism Mediated by a Male-Flower Parasitic Fungus". American Journal of Botany. 87 (3): 440–445. doi:10.2307/2656640. hdl:10088/12159. JSTOR 2656640. PMID 10719005.

- ^ Disney, R.H.L. (2007). "Natural History of the Scuttle Fly, Megaselia scalaris". Annual Review of Entomology. 53: 39–60. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.53.103106.093415. PMID 17622197.

- ^ Stireman, John O. (1 September 2002). "Learning in the Generalist Tachinid Parasitoid Exorista Mella Walker (Diptera: Tachinidae)". Journal of Insect Behavior. 15 (5): 689–706. doi:10.1023/A:1020752024329. S2CID 36686371.

- ^ a b Foote, B.A. (1995). "Biology of Shore Flies". Annual Review of Entomology. 40: 417–442. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.40.010195.002221.

- ^ Gullan, P.J.; Cranston, P.S. (2009). The Insects: An Outline of Entomology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-4051-4457-5.

- ^ Dickinson, Michael H. (1999). "Haltere–mediated equilibrium reflexes of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 354 (1385): 903–916. doi:10.1098/rstb.1999.0442. PMC 1692594. PMID 10382224.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Resh, Vincent H.; Cardé, Ring T. (2009). Encyclopedia of Insects. Academic Press. pp. 284–297. ISBN 978-0-08-092090-0.

- ^ a b c d Hoell, H. V.; Doyen, J. T.; Purcell, A. H. (1998). Introduction to Insect Biology and Diversity (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 493–499. ISBN 978-0-19-510033-4.

- ^ Haag, Juergen; Borst, Alexander (2002). "Dendro-dendritic interactions between motion-sensitive large-field neurons in the fly". The Journal of Neuroscience. 22 (8): 3227–3233. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03227.2002. PMC 6757520. PMID 11943823.

- ^ Hausen, Klaus; Egelhaaf, Martin (1989). "Neural Mechanisms of Visual Course Control in Insects". In Stavenga, Doekele Gerben; Hardie, Roger Clayton (eds.). Facets of Vision. pp. 391–424. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-74082-4_18. ISBN 978-3-642-74084-8.

- ^ Egelhaaf, Martin (1985). "On the neuronal basis of figure-ground discrimination by relative motion in the visual system of the fly". Biological Cybernetics. 52 (3): 195–209. doi:10.1007/BF00339948. S2CID 227306897.

- ^ Kimmerle, Bernd; Egelhaaf, Martin (2000). "Performance of fly visual interneurons during object fixation". The Journal of Neuroscience. 20 (16): 6256–66. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06256.2000. PMC 6772600. PMID 10934276.

- ^ Eckert, Hendrik (1980). "Functional properties of the H1-neurone in the third optic Ganglion of the Blowfly, Phaenicia". Journal of Comparative Physiology. 135 (1): 29–39. doi:10.1007/BF00660179. S2CID 26541123.

- ^ a b Ruppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard, S.; Barnes, Robert D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology, 7th edition. Cengage Learning. pp. 735–736. ISBN 978-81-315-0104-7.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stocker, Reinhard F. (2005). "The organization of the chemosensory system in Drosophila melanogaster: a review". Cell and Tissue Research. 275 (1): 3–26. doi:10.1007/BF00305372. PMID 8118845. S2CID 23210046.

- ^ Zhu, Junwei J.; Zhang, Qing-he; Taylor, David B.; Friesen, Kristina A. (1 September 2016). "Visual and olfactory enhancement of stable fly trapping". Pest Management Science. 72 (9): 1765–1771. doi:10.1002/ps.4207. PMID 26662853.

- ^ Lakes-Harlan, Reinhard; Jacobs, Kirsten; Allen, Geoff R. (2007). "Comparison of auditory sense organs in parasitoid Tachinidae (Diptera) hosted by Tettigoniidae (Orthoptera) and homologous structures in a non-hearing Phoridae (Diptera)". Zoomorphology. 126 (4): 229–243. doi:10.1007/s00435-007-0043-3. S2CID 46359462.

- ^ "Strepsiptera: Stylops". Insects and their Allies. CSIRO. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ Langer, Mattias G.; Ruppersberg, J. Peter; Gorb, Stanislav N. (2004). "Adhesion Forces Measured at the Level of a Terminal Plate of the Fly's Seta". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 271 (1554): 2209–2215. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2850. JSTOR 4142949. PMC 1691860. PMID 15539345.

- ^ Gibb, Timothy J.; Oseto, Christian (2010). Arthropod Collection and Identification: Laboratory and Field Techniques. Academic Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-08-091925-6.

- ^ Deora, Tanvi; Singh, Amit Kumar; Sane, Sanjay P. (3 February 2015). "Biomechanical basis of wing and haltere coordination in flies". PNAS. 112 (5): 1481–1486. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.1481D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1412279112. PMC 4321282. PMID 25605915.

- ^ Dickinson, Michael H; Tu, Michael S (1 March 1997). "The function of dipteran flight muscle". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology. 116 (3): 223–238. doi:10.1016/S0300-9629(96)00162-4.

- ^ Dickinson, Michael H. (2005). "The initiation and control of rapid flight manoeuvres in fruit flies". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 45 (2): 274–281. doi:10.1093/icb/45.2.274. PMID 21676771. S2CID 7306151.

- ^ Sourakov, Andrei (2011). "Faster than a flash: The fastest visual startle reflex response is found in a long-legged fly, Condylostylus sp. (Dolichopodidae)". The Florida Entomologist. 94 (2): 367–369. doi:10.1653/024.094.0240. S2CID 86502767.

- ^ Townsend, Charles H.T. (1927). "On the Cephenemyia mechanism and the Daylight-Day circuit of the Earth by flight". Journal of the New York Entomological Society. 35 (3): 245–252. JSTOR 25004207.

- ^ Langmuir, Irving (1938). "The speed of the deer fly". Science. 87 (2254): 233–234. Bibcode:1938Sci....87..233L. doi:10.1126/science.87.2254.233. PMID 17770404.

- ^ Townsend, Charles H.T. (1939). "Speed of Cephenemyia". Journal of the New York Entomological Society. 47 (1): 43–46. JSTOR 25004791.

- ^ Berenbaum, M. (1999). "Getting Up to Speed". American Entomologist. 45: 4–5. doi:10.1093/ae/45.1.4.

- ^ Johnson, C.G.; Taylor, L.R.; T.R.E. Southwood (1962). "High altitude migration of Oscinella frit L. (Diptera: Chloropidae)". Journal of Animal Ecology. 31 (2): 373–383. doi:10.2307/2148. JSTOR 2148.

- ^ Svensson, BO G.; Janzon, Lars-ÅKE (1984). "Why does the hoverfly Metasyrphus corollae migrate?". Ecological Entomology. 9 (3): 329–335. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.1984.tb00856.x. S2CID 83629356.

- ^ Wellington, W. G.; Fitzpatrick, Sheila M. (2012). "Territoriality in the Drone Fly, Eristalis tenax (Diptera: Syrphidae)". The Canadian Entomologist. 113 (8): 695–704. doi:10.4039/Ent113695-8. S2CID 86181761.

- ^ Dodson, Gary; Yeates, David (1990). "The mating system of a bee fly (Diptera: Bombyliidae). II. Factors affecting male territorial and mating success". Journal of Insect Behavior. 3 (5): 619–636. doi:10.1007/BF01052332. S2CID 25061334.

- ^ a b Becerril-Morales, Felipe; Macías-Ordóñez, Rogelio (2009). "Territorial contests within and between two species of flies (Diptera: Richardiidae) in the wild". Behaviour. 146 (2): 245–262. doi:10.1163/156853909X410766.

- ^ Alcock, John; Schaefer, John E. (1983). "Hilltop territoriality in a Sonoran desert bot fly (Diptera: Cuterebridae)". Animal Behaviour. 31 (2): 518. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(83)80074-8. S2CID 53180240.

- ^ Yuval, B.; Bouskila, A. (1 March 1993). "Temporal dynamics of mating and predation in mosquito swarms". Oecologia. 95 (1): 65–69. Bibcode:1993Oecol..95...65Y. doi:10.1007/BF00649508. PMID 28313313. S2CID 22921039.

- ^ Downes, J. A. (1969). "The swarming and mating flight of Diptera". Annual Review of Entomology. 14: 271–298. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.14.010169.001415.

- ^ a b Gullan, P.J.; Cranston, P.S. (2005). The Insects: An Outline of Entomology 3rd Edition. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 499–505. ISBN 978-1-4051-4457-5.

- ^ Manual of Nearctic Diptera

- ^ Brown, Lesley (1993). The New shorter Oxford English dictionary on historical principles. Clarendon. ISBN 978-0-19-861271-1.

- ^ Lancaster, Jill; Downes, Barbara J. (2013). Aquatic Entomology. Oxford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-19-957321-9.

- ^ Chapman, R. F. (1998). The Insects; Structure & Function. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57890-5.

- ^ Meier, Rudolf; Kotrba, Marion; Ferrar, Paul (August 1999). "Ovoviviparity and viviparity in the Diptera". Biological Reviews. 74 (3): 199–258. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1999.tb00186.x. S2CID 86129322.

- ^ Mcmahon, Dino P.; Hayward, Alexander (April 2016). "Why grow up? A perspective on insect strategies to avoid metamorphosis". Ecological Entomology. 41 (5): 505–515. doi:10.1111/een.12313. S2CID 86908583.

- ^ Gillott, Cedric (2005). Entomology (3 ed.). Springer. pp. 614–615.

- ^ "Crampton, G. The TemporalAbdominal Structures of Male Diptera". Archived from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ Sex with a twist in the tail: The common-or-garden housefly

- ^ Papavero, N. (1977). The World Oestridae (Diptera), Mammals and Continental Drift. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-1306-2. ISBN 978-94-010-1308-6. S2CID 43307061.

- ^ Hendrichs, J.; Cooley, S. S.; Prokopy, R. J. (1992). "Post-feeding bubbling behaviour in fluid-feeding Diptera: concentration of crop contents by oral evaporation of excess water". Physiological Entomology. 17 (2): 153–161. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3032.1992.tb01193.x. S2CID 86705683.

- ^ Gomes, Guilherme; Köberle, Roland; Von Zuben, Claudio J.; Andrade, Denis V. (2018). "Droplet bubbling evaporatively cools a blowfly". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 5464. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.5464G. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-23670-2. PMC 5908842. PMID 29674725.

- ^ Marshall, S.A.; Kirk-Spriggs, A.H. (2017). "Natural history of Diptera". In Kirk-Spriggs, A.H.; Sinclair, B.J. (eds.). Manual of Afrotropical Diptera. Volume 1. Introductory chapters and keys to Diptera families. Suricata 4. Pretoria: South African National Biodiversity Institute. pp. 135–152.

- ^ van Breug, Floris; Dickinson, Michael H. (2017). "Superhydrophobic diving flies ( Ephydra hians ) and the hypersaline waters of Mono Lake". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (51): 13483–13488. Bibcode:2017PNAS..11413483V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1714874114. PMC 5754803. PMID 29158381.

- ^ Collins, Robert (2004). What eats flies for dinner?. Shortland Mimosa. ISBN 978-0-7327-3471-8.

- ^ Gilbert, Francis (2004). The evolution of imperfect mimicry in hoverflies (PDF). CABI. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ Rashed, A.; Khan, M. I.; Dawson, J. W.; Yack, J. E.; Sherratt, T. N. (2008). "Do hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae) sound like the Hymenoptera they morphologically resemble?". Behavioral Ecology. 20 (2): 396–402. doi:10.1093/beheco/arn148.

- ^ Pie, Marcio R.; Del-Claro, Kleber (2002). "Male-male agonistic behavior and ant-mimicry in a Neotropical richardiid (Diptera: Richardiidae)". Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment. 37: 19–22. doi:10.1076/snfe.37.1.19.2114. S2CID 84201196.

- ^ Whitman, D. W.; Orsak, L.; Greene, E. (1988). "Spider mimicry in fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae): Further experiments on the deterrence of jumping spiders (Araneae: Salticidae) by Zonosemata vittigera (Coquillett)". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 81 (3): 532–536. doi:10.1093/aesa/81.3.532.

- ^ Akre, Roger D.; Garnett, William B.; Zack, Richard S. (1990). "Ant hosts of Microdon (Diptera: Syrphidae) in the Pacific Northwest". Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society. 63 (1): 175–178. JSTOR 25085158.

- ^ Godfray, H. C. J. (1994). Parasitoids: Behavioral and Evolutionary Ecology. Princeton University Press. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-691-00047-3.

- ^ Eslin, Patrice; Doury, Géraldine (2006). "The fly Drosophila subobscura: A natural case of innate immunity deficiency". Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 30 (11): 977–983. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2006.02.007. PMID 16620975.

- ^ Wyman, Leland Clifton (1983). "Navajo Ceremonial System" (PDF). Handbook of North American Indians. p. 539. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

Nearly every element in the universe may be thus personalized, and even the least of these such as tiny Chipmunk and those little insect helpers and mentors of deity and man in the myths, Big Fly (Dǫ'soh) and Ripener (Corn Beetle) Girl ('Anilt'ánii 'At'ééd) (Wyman and Bailey 1964:29–30, 51, 137–144), are as necessary for the harmonious balance of the universe as is the great Sun.

- ^ Wyman, Leland Clifton; Bailey, Flora L. (1964). Navaho Indian Ethnoentomology. Anthropology Series. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780826301109. LCCN 64024356.

- ^ "Native American Fly Mythology". Native Languages of the Americas website.

- ^ "Βεελζεβούλ, ὁ indecl. (v.l. Βεελζεβούβ and Βεεζεβούλ W-S. §5, 31, cp. 27 n. 56) Beelzebul, orig. a Philistine deity; the name בַּעַל זְבוּב means Baal (lord) of the flies (4 Km 1:2, 6; Sym. transcribes βεελζεβούβ; Vulgate Beelzebub; TestSol freq. Βεελζεβούλ,-βουέλ).", Arndt, W., Danker, F. W., & Bauer, W. (2000). A Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian literature (3rd ed.) (173). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ "1. According to 2 Kgs 1:2–6 the name of the Philistine god of Ekron was Lord of the Flies (Heb. ba‘al zeaûḇ), from whom Israel’s King Ahaziah requested an oracle.", Balz, H. R., & Schneider, G. (1990–). Vol. 1: Exegetical dictionary of the New Testament (211). Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans.

- ^ "For etymological reasons, Baal Zebub must be considered a Semitic god; he is taken over by the Philistine Ekronites and incorporated into their local cult.", Herrmann, "Baal Zebub", in Toorn, K., Becking, B., & Horst, P. W. (1999). Dictionary of deities and demons in the Bible DDD (2nd extensively rev. ed.) (154). Leiden; Boston; Grand Rapids, Mich.: Brill; Eerdmans.

- ^ a b c d e f Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. The British Museum Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-7141-1705-8.

- ^ Haynes, Dawn. The Symbolism and Significance of the Butterfly in Ancient Egypt (PDF).

- ^ Forbes Irving, Paul M. C. (1990). Metamorphosis in Greek Myths. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 315. ISBN 0-19-814730-9.

- ^ Lucian; C. D. N. Costa (2005). Lucian: Selected Dialogues. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-19-925867-3.

- ^ Belfiore, Elizabeth S. (2000). Murder among Friends: Violation of Philia in Greek Tragedy. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-19-513149-9.

- ^ a b c Stagman, Myron (11 August 2010). Shakespeare's Greek Drama Secret. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 205–208. ISBN 978-1-4438-2466-8.

- ^ Walker, John Lewis (2002). Shakespeare and the Classical Tradition: An Annotated Bibliography, 1961–1991. Taylor & Francis. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-8240-6697-0.

- ^ Dethier, Vincent G. (1962). To Know a Fly. San Francisco: Holden-Day.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Insects, p. 242

- ^ "Fly on the Wall". British Film Institute. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Ma, Kevin Y.; Chirarattananon, Pakpong; Fuller, Sawyer B.; Wood, Robert J. (3 May 2013). "Controlled flight of a biologically inspired, insect-scale robot". Science. 340 (6132): 603–607. Bibcode:2013Sci...340..603M. doi:10.1126/science.1231806. PMID 23641114. S2CID 21912409.

- ^ Gray, Richard (12 September 2013). "Jurassic Park ruled out – dinosaur DNA could not survive in amber". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Mulla, Mir S.; Chansang, Uruyakorn (2007). "Pestiferous nature, resting sites, aggregation, and host-seeking behavior of the eye fly Siphunculina funicola (Diptera: Chloropidae) in Thailand". Journal of Vector Ecology. 32 (2): 292–301. doi:10.3376/1081-1710(2007)32[292:pnrsaa]2.0.co;2. PMID 18260520. S2CID 28636403.

- ^ "Why use the fly in research?". YourGenome. 19 June 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ Ashlock, P. D. (1974). "The Uses of Cladistics". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 5 (1): 81–99. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.05.110174.000501.

- ^ Joseph, Isaac; Mathew, Deepu G.; Sathyan, Pradeesh; Vargheese, Geetha (2011). "The use of insects in forensic investigations: An overview on the scope of forensic entomology". Journal of Forensic Dental Sciences. 3 (2): 89–91. doi:10.4103/0975-1475.92154. PMC 3296382. PMID 22408328.

- ^ Ogunleye, R. F.; Edward, J. B. (2005). "Roasted maggots (Dipteran larvae) as a dietary protein source for laboratory animals". African Journal of Applied Zoology and Environmental Biology. 7: 140–143.

- ^ Fleming, Nic (4 June 2014). "How insects could feed the food industry of tomorrow". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ "Why are insects not allowed in animal feed?" (PDF). All About Feed. August 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ Stegman, Sylvia; Steenvoorde, Pascal (2011). "Maggot debridement therapy". Proceedings of the Netherlands Entomological Society Meeting. 22: 61–66.

- ^ Diaz-Roa, A.; Gaona, M. A.; Segura, N. A.; Suárez, D.; Patarroyo, M.A.; Bello, F. J. (August 2014). "Sarconesiopsis magellanica (Diptera: Calliphoridae) excretions and secretions have potent antibacterial activity". Acta Tropica. 136: 37–43. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.04.018. PMID 24754920.

- ^ Gilead, L.; Mumcuoglu, K. Y.; Ingber, A. (16 August 2013). "The use of maggot debridement therapy in the treatment of chronic wounds in hospitalised and ambulatory patients". Journal of Wound Care. 21 (2): 78–85. doi:10.12968/jowc.2012.21.2.78. PMID 22584527.

- ^ Berenbaum, May (2007). "A mite unappetizing" (PDF). American Entomologist. 53 (3): 132–133. doi:10.1093/ae/53.3.132. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2010.

- ^ Colangelo, Matt (9 October 2015). "A Desperate Search for Casu Marzu, Sardinia's Illegal Maggot Cheese". Food and Wine. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ Brones, Anna (15 April 2013). "Illegal food: step away from the cheese, ma'am". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

Further reading

- Blagoderov, V.A., Lukashevich, E.D. & Mostovski, M.B. (2002)). "Order Diptera". In: Rasnitsyn, A.P. and Quicke, D.L.J. The History of Insects, Kluwer pp.–227–240.

- Colless, D.H. & McAlpine, D.K. (1991). Diptera (flies), pp. 717–786. In: The Division of Entomology. Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Canberra (spons.), The Insects of Australia. Melbourne University Press.

- Hennig, Willi. "Diptera (Zweifluger)". Handb. Zool. Berl. 4 (2) (31):1–337. General introduction with key to World Families (in German).

- Oldroyd, Harold (1965). The Natural History of Flies. W. W. Norton.

- Séguy, Eugène (1924–1953). Diptera: recueil d'etudes biologiques et systematiques sur les Dipteres du Globe (Collection of biological and systematic studies on Diptera of the World). 11 vols. Part of Encyclopedie Entomologique, Serie B II: Diptera.

- Séguy, Eugène (1950). La Biologie des Dipteres.

- Thompson, F. Christian. "Sources for the Biosystematic Database of World Diptera (Flies)" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture, Systematic Entomology Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2015.

External links

General

- The Systema Dipterorum Database site

- The Diptera.info portal with galleries and discussion forums

- FLYTREE – dipteran phylogeny. Archived 13 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- The Dipterists Forum – The Society for the study of flies

- BugGuide

- The World Catalog of Fossil Diptera

- The Tree of Life Project

Anatomy

Describers