Eadwine Psalter

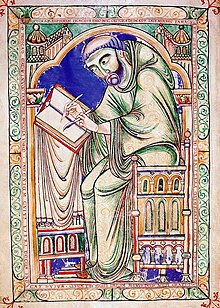

The Eadwine Psalter or Eadwin Psalter is a heavily illuminated 12th-century psalter named after the scribe Eadwine, a monk of Christ Church, Canterbury (now Canterbury Cathedral), who was perhaps the "project manager" for the large and exceptional book. The manuscript belongs to Trinity College, Cambridge (MS R.17.1) and is kept in the Wren Library. It contains the Book of Psalms in three languages: three versions in Latin, with Old English and Anglo-Norman translations, and has been called the most ambitious manuscript produced in England in the twelfth century. As far as the images are concerned, most of the book is an adapted copy, using a more contemporary style, of the Carolingian Utrecht Psalter, which was at Canterbury for a period in the Middle Ages. There is also a very famous full-page miniature showing Eadwine at work, which is highly unusual and possibly a self-portrait.[1]

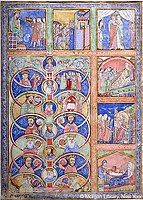

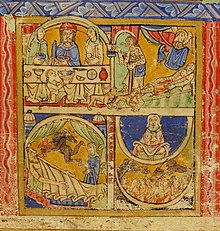

In addition to this, there is a prefatory cycle of four folios, so eight pages, fully decorated with a series of miniatures in compartments showing the Life of Christ, with parables and some Old Testament scenes. These pages, and perhaps at least one other, were removed from the main manuscript at some point and are now in the British Library, Victoria and Albert Museum (with one each), and two in the Morgan Library in New York.[2]

It was produced around the mid-century, perhaps 1155–60,[3] and perhaps in two main campaigns of work, one in the 1150s and the other the decade after.[4] It was sometimes called the "Canterbury Psalter" in the past, as in the 1935 monograph by M. R. James, but this is now avoided, if only to avoid confusion with other manuscripts, including the closely related Harley Psalter and the Great Canterbury Psalter (or Anglo-Catalan Psalter, Paris Psalter), which are also copies made in Canterbury of the Utrecht Psalter.

Contents

Text

The book is large, with 281 vellum folios or leaves (two-sided) in Cambridge, measuring an average 455 by 326 millimetres (17.9 in × 12.8 in).[5] The four detached leaves have presumably been trimmed and are now 400–405 mm x 292–300 mm.[6] The texts are: "a calendar, triple Metrical Psalms ... canticles, two continuous commentaries, two prognostications".[7]

The three main different Latin versions of the Psalms are given side by side. In the order they occur on the verso pages, these are the "Gallican" version, a translation from the Greek Septuagint which was used by most of the Western church, the "Roman", the Gallican version as corrected by Saint Jerome from the Hebrew Bible, which was used by churches in Rome,[8] but was also an Anglo-Saxon favourite, especially at Canterbury.[9] Last comes the "Hebrew" version, or Versio juxta Hebraicum, Jerome's translation from the Hebrew Bible.[10] The columns reverse their sequence on recto pages, so that the Gallican column, which has a larger text size, is always nearest the edge of the page, and the Hebrew nearest the bound edge.[11]

Between the lines of the text of the psalms, the "Hebrew" version has a translation into contemporary Norman-French, which represents the oldest surviving text of the psalms in French, the "Roman" version has a translation into Old English, and the "Gallican" version has Latin notes.[12] The Hebrew version was "a scholarly rather than a liturgical text", and related more to continental scholarly interests, especially those at Fleury Abbey.[13]

There are a number of Psalters with comparable Latin texts, and a number of luxury illuminated psalters, but the combination in a single manuscript of the scholarly psalterium triplex with a very large programme of illumination, and translations into two vernacular languages, is unique.[14] The psalter was "a tool for study and teaching" rather than a display manuscript for the altar.[15]

The Old English translation contains a number of errors which "have been explained as the result of uncritical copying of an archaic text at a time when the language was no longer in current use".[16]

Illumination

The manuscript is the most extensively decorated 12th-century English manuscript. There are 166 pen drawings with watercolour (a traditional Anglo-Saxon style), based on their counterparts in Utrecht, which lack colour.[17] There are also the four painted leaves, now detached, with the biblical cycle, with some 130 scenes; there may have been at least one more page originally.[18] These may be referred to as the "Picture Leaves".[19] At the end of the book there is the full-page portrait of Eadwine, followed by drawings with colour showing Christ Church, Canterbury and its water channels, one over a full opening, and the other more schematic and on a single page. These are thought to be at least afterthoughts, added to what were intended as blank flyleaves, as found in a number of other manuscripts.[20] Throughout the text very many initials are decorated, with over 500 "major" initials fully painted with gold highlights, mostly at the first letter of each of the three text versions of each psalm.[21]

The prefatory miniature cycle is divided stylistically. Of the eight pages, six and a half are in one style, but most of the Victoria and Albert folio in another. This is usually thought to mark a change of artist. The two styles can be related to those of the St Albans Psalter and the Lambeth Bible respectively. Though comparison with the Utrecht-derived images in Cambridge is complicated by the different technique and the many stylistic features retained from the original, the first artist seems closest to these.[22]

The idea of such a cycle was already about, and one key exemplar was probably the 6th-century Italian St Augustine Gospels, a key relic of the founder of the cathedral's rival St Augustine's Abbey, Canterbury, where it then was, though it has also since found its way to a Cambridge college. This has one surviving page (of an original three, at least) with compartmented scenes of the life of Christ, which include many miracles and incidents from the ministry of Jesus rarely depicted by the High Middle Ages. The Eadwine pages include one of these scenes, from the start of Luke 9, 58 (and Matthew 8, 20): "et ait illi Iesus vulpes foveas habent et volucres caeli nidos Filius autem hominis non habet ubi caput reclinet" – "Jesus said to him: The foxes have holes, and the birds of the air nests: but the Son of man hath not where to lay his head."[23] For the iconography of the prefatory cycle, see below.

The copies of Utrecht images are compressed to fit the different format, but generally rather close. However, the sense of the landscape setting suffers considerably. Kenneth Clark commented that "the Utrecht Psalter is full of landscape motives taken from Hellenistic painting, and its impressionistic scribbles still imply a sense of light and space. There is no simpler way to show the triumph of symbol over sensation in the middle ages than to compare its pages with [their Eadwine Psalter equivalents]."[24]

Eadwine and his portrait

It is unclear who Eadwine was and what role he played in the creation of the manuscript; the documentary traces of monastic Eadwines (and Edwins and Adwins etc) of about the right time and place are few, and hard to fit to the facts and statements of the manuscript. The inscription around the portrait declares that he is sriptorum princeps (sic), "prince of scribes" (or "first among scribes"),[26] so he was probably one of the many scribes working on the manuscript, but probably also playing the main role in deciding the contents and organizing the work. He may also have paid for it, though he was certainly not the prior of Canterbury at the time, as these are all known, and Wybert or Wibert (r. 1153–1167) was prior for the most likely periods for the book's creation.[27]

His portrait is clearly of the conventional type of an author portrait, at this period most often seen in evangelist portraits at the start of the Gospels. These look right or forward to the pages following containing their work. Eadwine's is placed at the end of the book, after the text, so he looks left, back over it.[28]

As recorded by M. R. James:

"The following inscription in green and red capitals surrounds the picture beginning at the top on L.

SCRIPTOR (supply loquitur). SRIPTORUM (sic) PRINCEPS EGO NEC OBITURA DEINCEPS LAVS MEA NEC FAMA. QVIS SIM MEA LITTERA CLAMA. LITTERA. TE TVA SRIPTVRA QUEM SIGNAT PICTA FIGURA Ɵ- (top L. again). -Ɵ PREDICAT EADWINVM FAMA PER SECULA VIVUM. INGENIUM CVIVS LIBRI DECUS INDICAT HVIVS.

QVEM TIBI SEQUE DATVM MVNVS DEUS ACCIPE GRATVM."

which translates as:

Scribe: I am the chief of scribes, and neither my praise nor fame shall die; shout out, oh my letter, who I may be. Letter: By its fame your script proclaims you, Eadwine, whom the painted figure represents, alive through the ages, whose genius the beauty of this book demonstrates. Receive, O God, the book and its donor as an acceptable gift.[29]

The portrait, and the waterworks drawings that follow it, have sometimes been seen as later additions, though more recent scholarship is moving away from this view.[30] The portrait might then be a memorial added to commemorate a notable figure of the monastery in a book he had been closely associated with,[31] with the waterworks drawings also acting as a memorial to Prior Wibert, who had done considerable work on the water system. Some scholars see both aspects of the script and the portrait as evoking Eadwig Basan, the most famous of English scribes (and perhaps also the artist of the miniatures in his manuscripts), who was a monk at Christ Church Canterbury over a century earlier, in the last decades of Anglo-Saxon England.[32]

Scribes, artists and history

At least ten scribes contributed to the texts, at least five of them contributing to the Old English text, and at least six artists, who may overlap with the scribes. It is difficult to tell many of these apart.[33] It seems likely that Eadwine contributed to the scribing, but his hand cannot be confidently identified. However, at least according to T. A. Heslop, the bulk of the illumination, over 80% of the prefatory cycle and over 90% of the miniatures in the psalms and canticles, is by a single artist, who he calls the "Principal Illuminator".[34] To Heslop, the diverse styles and limited "guest appearances" of the other artists suggests that they are mobile laymen employed for the task by the monastery, of the sort who were even at this early date beginning to take over the illumination of manuscripts.[35]

The dating of the manuscript has been much discussed, mainly on stylistic grounds (regarding both the script and the illustrations), within the broad range 1130–1170. On folio 10 there is a marginal drawing of a comet, with a note in Old English (in which it is a "hairy star") that it is an augury; following the comet of 1066 the English evidently took comets seriously. This was thought to relate to the appearance of Halley's Comet in 1145, but another of 14 May 1147 is recorded in the Christ Church Annals, and the 1145 one is not. There were further comets recorded in 1165 and 1167, so the evidence from astronomy has not settled the question. Such a large undertaking would have taken many years to complete; the Anglo-Catalan Psalter was left unfinished in England, like many other ambitious manuscript projects.[36]

The current broad consensus is to date most of the book to 1155–60, but the portrait of Eadwine and the waterworks drawings to perhaps a decade later.[37] The large waterworks drawing shows the cathedral as it was before the major fire of 1174, which provoked the introduction of Gothic architecture to the cathedral, when William of Sens was brought in to rebuild the choir. The period also saw the momentous murder of Thomas Becket in 1170, and his rapid canonization as a saint in 1173; however his feast day is not included in the calendar.[38]

The book is included in the catalogue of the library of Christ Church made in Prior Eastry's inventory in the early fourteenth century. It was given by Thomas Nevile, Dean of Canterbury Cathedral, to Trinity College, Cambridge in the early seventeenth century, presumably without the prefatory folios, which are thought to have been removed around this time. The binding is 17th-century.[39]

By the early 19th century the detached folios were in the collection of William Young Ottley, the British Museum's print curator and a significant art collector, but no admirer of medieval art. At the sale in 1838, after his death in 1836, the sheets were individual lots and bought by different buyers.[40] The Victoria and Albert Museum's sheet fetched two guineas (£2 and 2 shillings). It was bought by the museum in 1894.[41] One of the two sheets in the Morgan Library passed through various hands and was bought by J.P. Morgan in 1911 and the other was added in 1927, after his death.[42] The British Museum bought their sheet in 1857.[43]

All the surviving parts of the original manuscript were reunited in the exhibition English Romanesque Art, 1066–1200 in London in 1984, though the catalogue entries, by Michael Kauffmann, did not relate the loose sheets to the main Cambridge manuscript,[44] although Hanns Swarzenski in 1938 and C. R. Dodwell in 1954 had already proposed this.[45]

Scenes in the prefatory miniatures

These pages "contain by far the largest New Testament cycle produced in England or anywhere else in the 12th century", with some 150 scenes.[46] The emphasis on the miracles and parables of Christ was most untypical in Romanesque cycles in general, which concentrated almost exclusively on the events commemorated by the feast days of the liturgical calendar. Ottonian cycles such as that in the Codex Aureus of Echternach still show the miracles and parables, but the cycle here has more scenes than any Ottonian one. Sources for the selection of scenes are probably considerably older than the 12th century, and might possibly go back as far as the St Augustine Gospels, of about 600, which were then at Canterbury, and no doubt more complete than now, or a similar very early cycle.[47]

On the other hand George Henderson argued that the cycle may have been planned specially for the Eadwine Psalter, based on direct reading of the bible, with the New Testament scenes sometimes "following the sequence of a particular gospel, at times constructing an intelligent first-hand synthesis of more than one gospel."[48]

There is usually thought to have been a fifth sheet covering the Book of Genesis, especially as there is one in the Great Canterbury/Anglo-Catalan Psalter, which has a closely similar cycle.[49] The emphasis on the life of David, who appears in 5 scenes, as well as the Tree of Jesse, is appropriate for the figure regarded as the author of the psalms.[50]

All the pages use a basic framework of twelve square compartments divided by borders, which may contain a single scene, or several. In the latter case, usually they are divided horizontally to give two wide spaces. Within these two or more scenes may be contained without formally interrupting the picture space. The scenes shown can be summarized as:[51]

Morgan Library, M 724[52]

- Recto: 12 squares, several with more than 1 scene. 1–7 are the story of Moses, including Moses trampling on Pharaoh's Crown, "a Jewish legend popularized by Josephus". 8 is Joshua, 9–12 Saul and David

- Verso: 7 scenes, six squares and a large compartment. 1–2 David. 3 a large compartment with a Tree of Jesse, which includes the Annunciation, Annunciation to Zacharias, and the wedding of Mary and Joseph. 4 Visitation, 5–6 Birth and naming of John the Baptist, 7 Nativity of Jesus.

British Library

- Recto: 12 scenes completing the Nativity cycle, from the Annunciation to the Shepherds to Herod's suicide, an uncommon scene (and a medieval distortion of Josephus).

- Verso: 12 squares, some with 2 scenes, all showing the ministry of Jesus, from the Baptism of Jesus to the Raising of Jairus' daughter

Morgan Library, M 521[53]

- Recto: 12 squares, but each with at least two scenes, all with miracles and parables of Jesus. The last (bottom right) square has the story of the Prodigal Son in 8 scenes, the bottom centre the story of Dives and Lazarus in four.

- Verso: 12 squares, but each with at least two scenes: 1–7 miracles and parables. 8 Triumphal entry into Jerusalem, 9–12 Passion to the Arrest of Jesus

Victoria and Albert Museum

- Recto: 12 squares, most with two scenes: the Passion continues to the Deposition of Christ

- Verso: 12 squares, most with two scenes: the burial through to the Ascension and Pentecost, though there is no Resurrection scene as such, a sign of the early origin of this choice of scenes.

-

Morgan leaf M.724 (recto)

-

Morgan leaf M.724 (verso)

-

Morgan leaf M.521 (verso)

-

V&A leaf (recto)

Notes

- ^ Gerry; Trinity Coll., MS. R.17.1; on its fame: Ross, 45; Karkov, 299

- ^ Gerry: "New York, Morgan Lib., MSS M.521 and M.724; London, British Library, Add MS 37472; London, V&A, MS. 661"

- ^ Karkov, 289; Gibson, 209

- ^ Gerry

- ^ PUEM

- ^ Zarnecki, 111–112

- ^ PUEM

- ^ Trinity

- ^ Karkov, 292

- ^ Trinity

- ^ Trinity

- ^ Trinity

- ^ Karkov, 292

- ^ See Karkov, 292, PUEM on multi-lingual MS., and Gibson, 26 on prefatory cycles in pasalters.

- ^ Dodwell, 338

- ^ Zarnecki, 119

- ^ Gibson, 25; Dodwell, 338

- ^ Gibson, 25

- ^ Gibson, 26, 43

- ^ Dodwell, 357

- ^ Gibson, 25

- ^ Gibson, 25–27, 59–60; Dodwell, 336–338

- ^ Gibson, 29; Dodwell, 338

- ^ Clark, Kenneth, Landscape into Art, 1949, p. 17 (in Penguin edn of 1961)

- ^ Utrecht version

- ^ Michael Kaufmann in Zarnecki, 119 translates as "prince"; below P. Heslop as "chief"

- ^ Gibson, 184; Ross, Chapter 3; Karkov, 289; Dodwell, 355–359

- ^ Gibson, 183–184; Karkov, 299–300

- ^ Translation by P. Heslop in Gibson, p.180, quoted by Karkov, 302

- ^ Karkov, 299–301, 304–306

- ^ Karkov, 304–306; Ross, 49; Dodwell, 357 argues against this

- ^ Karkov, 295–299; Gibson, 24, 85–87

- ^ PUEM, Karkov, 289, who has been followed where counts differ.

- ^ Gibson, 59

- ^ Gibson, 61

- ^ Dodwell, 338–340; Gibson, 61, 164

- ^ Karkov, 289; V&A; Gerry; PUEM; Dodwell, 357 – some with variations of phrasing

- ^ Dodwell, 357

- ^ PUEM; V&A

- ^ Zarnecki, 111–112

- ^ V&A

- ^ Morgan Library CORSAIR online entries, M521 and M724; Zarnecki, 111–112

- ^ Zarnecki, 111

- ^ Zarnecki, #s 47–50, 62

- ^ Gibson, 25–27

- ^ Zarnecki, 111

- ^ Zarnecki, 111–112; V&A. However Dodwell, 336–337 allows for a good deal of originality from the Canterbury artists.

- ^ in Gibson, 35–42

- ^ Zarnecki, 111

- ^ Dodwell, 336

- ^ Zarnecki, 111–112, lists all of them

- ^ Morgan

- ^ Morgan

References

- Dodwell, C.R.; The Pictorial arts of the West, 800–1200, 1993, Yale UP, ISBN 0300064934

- Gerry, Kathryn B., "Eadwine Psalter." Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed June 28, 2015, Subscription required

- Gibson, Margaret, Heslop, T. A., Pfaff, Richard W. (Eds.), The Eadwine Psalter: Text, Image, and Monastic Culture in Twelfth-Century Canterbury, 1992, Penn State University Press, Google Books

- Karkov, C., "The Scribe Looks Back; Anglo-Saxon England and the Eadwine Psalter", in: The Long Twelfth-Century View of the Anglo-Saxon Past, Eds. Martin Brett, David A. Woodman, 2015, Ashgate Publishing Ltd., ISBN 1472428196, 9781472428196, Google Books

- "Morgan" = Morgan Library, Corsair database, PDF of curators file notes on their sheets

- "PUEM"= The Production and Use of English Manuscripts, 1060 to 1220, Universities of Leicester and Leeds

- Ross, Leslie, Artists of the Middle Ages, 2003, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0313319030, 9780313319037, Google books

- "Trinity" = Online catalogue Archived 13 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine of the manuscripts of Trinity College, Cambridge, by M. R. James

- "V&A"= The V&A's page on its sheet

- Zarnecki, George and others; English Romanesque Art, 1066–1200, 1984, Arts Council of Great Britain, (Catalogue #s 47–50, 62), ISBN 0728703866

Further reading

- M. R. James, ed., The Canterbury Psalter, London, 1935

- P. Binski and S. Panayotova, eds, The Cambridge Illuminations; Ten Centuries of Book Production in the Medieval West, London, 2005, cat. no. 25, pp. 90–92

- The Appended Images of the Eadwine Psalter: A New Appraisal of Their Commemorative, Documentary, and Institutional Functions, Baker, Katherine S. (2008), Master's Thesis (78 pages) Emory University

External links

- Full view of Eadwine Psalter, with turn-the-pages, & zoom Archived 27 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- All illustrated pages, black and white images Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, with similar sections on the Utrecht Psalter and its other derivatives, from the Warburg Institute

- British Library, page on its sheet

- "The Waterworks Drawing from the Eadwine Psalter" Archived 16 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine Canterbury Cathedral website, published on February 1, 2014

- Morgan Library, page on MS M.521v

- Old English Poetry in Facsimile Project. Digital edition to facsimile and modern translation of the interlineal Old English metrical glosses of Psalms 90-95; ed. Foys, Martin et al. Center for the History of Print and Digital Culture. Madison, 2019-.