English politics

| This article is part of a series within the Politics of the United Kingdom on the |

|

|---|

Politics of England forms the major part of the wider politics of the United Kingdom, with England being more populous than all the other countries of the United Kingdom put together. As England is also by far the largest in terms of area and GDP, its relationship to the UK is somewhat different from that of Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland. The English capital London is also the capital of the UK, and English is the dominant language of the UK (not officially, but de facto). Dicey and Morris (p26) list the separate states in the British Islands. "England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, the Isle of Man, Jersey, Guernsey, Alderney, and Sark.... is a separate country in the sense of the conflict of laws, though not one of them is a State known to public international law." But this may be varied by statute.

The United Kingdom is one state for the purposes of the Bills of Exchange Act 1882. Great Britain is a single state for the purposes of the Companies Act 1985. Traditionally authors referred to the legal unit of England and Wales as "England" although this usage is becoming politically unacceptable in the last few decades. The Parliament of the United Kingdom is located in London, as is its civil service, HM Treasury and most of the official residences of the monarchy. In addition, the state bank of the UK is known as the "Bank of England".

Though associated with England for some purposes, the Isle of Man, Jersey and Guernsey have their own parliaments, and are not part of the United Kingdom, the European Union or England.

Prior to the Union, in 1707, England was ruled by a monarch and the Parliament of England. Since the Union, England has not had its own government.

History

Pre-Union politics

The English Parliament traces its origins to the Anglo-Saxon Witenagemot. Hollister argues that:

- In an age lacking precise definitions of constitutional relationships, the deeply ingrained custom that the king governed in consultation with the Witan, implicit in almost every important royal document of the period, makes the Witenagemot one of Anglo-Saxon England's fundamental political institutions.[1]

In 1066, William of Normandy brought a feudal system, where he sought the advice of a council of tenants-in-chief and ecclesiastics before making laws. In 1215, the tenants-in-chief secured the Magna Carta from King John, which established that the king may not levy or collect any taxes (except the feudal taxes to which they were hitherto accustomed), save with the consent of his royal council, which slowly developed into a parliament.

In 1265, Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester summoned the first elected Parliament. The franchise in parliamentary elections for county constituencies was uniform throughout the country, extending to all those who owned the freehold of land to an annual rent of 40 shillings (Forty-shilling Freeholders). In the boroughs, the franchise varied across the country; individual boroughs had varying arrangements.

This set the scene for the so-called "Model Parliament" of 1295 adopted by Edward I. By the reign of Edward II, Parliament had been separated into two Houses: one including the nobility and higher clergy, the other including the knights and burgesses, and no law could be made, nor any tax levied, without the consent of both Houses as well as of the Sovereign.

The Laws in Wales Acts of 1535–42 annexed Wales as part of England and brought Welsh representatives to Parliament.

When Elizabeth I was succeeded in 1603 by the Scottish King James VI, (thus becoming James I of England), the countries both came under his rule but each retained its own Parliament. James I's successor, Charles I, quarrelled with the English Parliament and, after he provoked the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, their dispute developed into the English Civil War. Charles was executed in 1649 and under Oliver Cromwell's Commonwealth of England the House of Lords was abolished, and the House of Commons made subordinate to Cromwell. After Cromwell's death, the Restoration of 1660 restored the monarchy and the House of Lords.

Amidst fears of a Roman Catholic succession, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 deposed James II (James VII of Scotland) in favour of the joint rule of Mary II and William III, whose agreement to the English Bill of Rights introduced a constitutional monarchy, though the supremacy of the Crown remained. For the third time, a Convention Parliament, i.e., one not summoned by the king, was required to determine the succession.

Post-Union politics

- Treaty of Union agreed by commissioners for each parliament on 22 July 1706.

- Acts of Union 1707, passed by both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

- Act of Union 1800, passed by both the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Once the terms of the Treaty of Union were agreed in 1706, Acts of Union were passed in both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland, which created a new Kingdom of Great Britain. The Acts dissolved both parliaments, replacing them with a new Parliament of the Kingdom of Great Britain based in the former home of the English parliament. All the traditions, procedures, and standing orders of the English parliament were retained, as were the incumbent officers, and English members comprised the overwhelming majority of the new body. It was not even considered necessary to hold a new general election. While Scots law and Scottish legislation remained separate, new legislation for both former kingdoms was now dealt with by the new parliament.

After the Hanoverian George I ascended the throne in 1714 through an Act of Parliament, power began to shift from the Sovereign, and by the end of his reign the position of the ministers – who had to rely on Parliament for support – was cemented. Towards the end of the 18th century the monarch still had considerable influence over Parliament, which was dominated by the English aristocracy and by patronage, but had ceased to exert direct power: for instance, the last occasion Royal Assent was withheld, was in 1708 by Queen Anne. At general elections the vote was restricted to freeholders and landowners, in constituencies that were out of date, so that in many "rotten boroughs" seats could be bought while major cities remained unrepresented. Reformers and Radicals sought parliamentary reform, but as the Napoleonic Wars developed the government became repressive against dissent and progress toward reform was stalled.

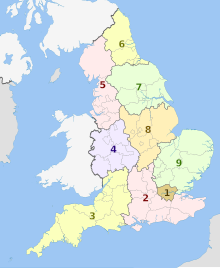

European Parliament

When the United Kingdom was a member of the European Union, members of the European Parliament for the United Kingdom were elected by twelve European constituencies, of which nine were within England, the others being one each covering Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Gibraltar, the only British Overseas Territory that was then part of the European Union, was included in the South West England European Constituency. At the last European Parliamentary election in which the United Kingdom participated, the English European constituencies were

| Constituency | Region | Seats | Pop. | per Seat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. London | Greater London | 9 | 7.4m | 822k |

| 2. South East England | South East | 10 | 8m | 800k |

| 3. South West England | South West, Gibraltar | 7 | 4.9m | 700k |

| 4. West Midlands | West Midlands | 7 | 5.2m | 740k |

| 5. North West England | North West | 9 | 6.7m | 745k |

| 6. North East England | North East | 3 | 2.5m | 833k |

| 7. Yorkshire and the Humber | Yorkshire and the Humber | 6 | 4.9m | 816k |

| 8. East Midlands | East Midlands | 6 | 4.1m | 683k |

| 9. East of England | East of England | 7 | 5.4m | 770k |

Post-devolution politics

While Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland voted for devolved legislatures in referendums in 1997 and 1998 (see 1997 Scottish devolution referendum, 1997 Welsh devolution referendum, and 1998 Northern Irish Belfast Agreement referendum) England has never had any referendum for Independence or devolved Assembly/Parliament.

The Scottish Parliament, Senedd and Northern Ireland Assembly were created by the UK parliament along with strong support from the majority of people of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and are not independent of the rest of the United Kingdom. However, this gave each country a separate and distinct political identity, leaving England (83% of the UK population) as the only part of the UK directly ruled in nearly all matters by the UK government in London, although London itself is devolved (see below).

While Scotland and Northern Ireland have always had separate legal systems to England (see Scots law and Northern Ireland law), this has not been the case with Wales (see English law, Welsh law and Contemporary Welsh Law). However, laws concerning the Welsh language, and also the Senedd, have created differences between the law in Wales, and the law in England, as they apply in Wales and not in England.

Regarding parliamentary matters, an anomaly called the West Lothian Question had come to the fore as a result of legislative devolution for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland without corresponding legislative devolution for England. Before devolution, for example, purely 'Scottish' legislation was debated at Westminster in a Scottish Grand Committee composed of just those MPs representing Scottish constituencies.

However, legislation was still subject to a vote of the entire House of Commons and this frequently led to legislation being passed despite the majority of Scottish MPs voting against. (This was especially true during the period of Conservative rule from 1979 to 1997 when the Conservative Party had an overall majority of MPs but only a handful representing Scotland and Wales.) Now that many Scottish matters are dealt with by the Scottish Parliament, the fact that MPs representing Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland can not vote on those issues as they affect Scotland, but can vote on those same issues as they affect England caused some disquiet. In 2015 English votes for English laws was passed by Westminster to solve this by giving English MPs a veto on legislation through Legislative Grand Committees. This system was discontinued in 2021.

The Campaign for an English Parliament is a proponent of a separate English parliament.

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is located at Westminster in London.

House of Commons

English members of parliament are elected at the same time as those for the rest of the UK. There are 533 English constituencies. Because of their large number, they form an inbuilt majority in the House of Commons. Even though Clause 81 of the Scotland Act 1998 equalised the English and Scottish electoral quota, and thereby reduced the number of Scottish members in the House of Commons from 72 to 59 MPs.

There is no English Grand Committee, however there is a Regional Affairs Committee which every English member can attend. For many years an anomaly known as the West Lothian question where MPs from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are able to vote on matters which only affect England only when those same issues are devolved to their own institutions and has become a major issue in recent years. In May 2015 the Conservative Party won an unexpected overall majority and pledged to commit to a manifesto promise to change parliamentary procedures and create a Legislative Grand Committee to give English MPs a much greater role in issues which affect only England (or England and Wales) as a solution to this issue known as "English votes for English laws" (EVEL). On 22 October 2015 following a heated debate in the House of Commons the Conservative Government led by David Cameron by 312 votes to 270 votes approved the proposals which came into effect immediately.[2] The legislative grand committee system was abolished in July 2021.[3]

House of Lords

The House of Lords also has an inbuilt English majority.

Members of the House of Lords who sit by virtue of their ecclesiastical offices are known as the Lords Spiritual. Formerly, the Lords Spiritual comprised a majority in the House of Lords, including the Church of England's archbishops, diocesan bishops, abbots, and priors. After 1539, however, only the archbishops and bishops continued to attend, for the Dissolution of the Monasteries suppressed the positions of abbot and prior. In 1642, during the English Civil War, the Lords Spiritual were excluded altogether, but they returned under the Clergy Act 1661.

The number of Lords Spiritual was further restricted by the Bishopric of Manchester Act 1847, and by later acts. Now, there can be no more than 26 Lords Spiritual in the Lords, but they always include the five most important prelates of the Church: the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Archbishop of York, the Bishop of London, the Bishop of Durham, and the Bishop of Winchester. Membership of the House of Lords also extends to the 21 longest-serving other diocesan bishops of the Church of England. The current Lords Spiritual, therefore, represent only the Church of England, although members of other churches and religions are appointed by the Queen as individuals and not ex officio.

Devolution within England

Former regional chambers

After power was to be devolved to Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales without a counterweight in England, a series of referendums were planned to establish elected regional assemblies in some of the regions. The first was held in London in 1998 and was passed. The London Assembly and Mayor of London of the Greater London Authority were created in 2000.

A referendum was held in North East England on 4 November 2004 but the proposal for an elected assembly was rejected. Plans to hold further referendums in other regions were then cancelled. The remaining eight Partnership Regional Assemblies were abolished in 2010 as part of a Sub-National Review of Economic Development and Regeneration with most of their functions transferring to the relevant Regional Development Agency and to Local Authority Leaders' Boards.[4]

Greater London Authority

Greater London has a certain amount of devolution, with the London Assembly and the directly elected Mayor of London. The Assembly was established on 3 July 2000, after a referendum in which 72% of those voting supported the creation of the Greater London Authority, which included the Assembly along with the Mayor of London. The referendum and establishment were largely contiguous with Scottish and Welsh devolution.

In Greater London, the 32 London borough councils have a status close to that of unitary authorities, but come under the Greater London Authority, which oversees some of the functions performed elsewhere in England by Counties including transport, policing, the fire brigade and also economic development.

The Mayor of London is also referred to as the "London Mayor", a form which helps to avoid confusion with the Lord Mayor of the City of London, the ancient and now mainly ceremonial role in the City of London. The Mayor of London is mayor of Greater London, which has a population of over 7.5 million while the City of London is only a small part of the modern city centre and has a population of fewer than 10,000.

Combined Authorities and Metro Mayors

Localism saw limited return of regional devolution, with devolved powers for combined authorities. The first Combined Authority, the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, was formed in 2011.

In 2014 it was announced that a Mayor of Greater Manchester would be created as leader of the Greater Manchester Combined Authority. In 2017 elections were held for Greater Manchester, the Liverpool City Region, the Tees Valley, West of England and the West Midlands as part of the devolution deals allowed by the Cities and Local Government Devolution Act 2016. The delayed election for the South Yorkshire Mayoral Combined Authority followed in May 2018. The East Midlands Combined Authority (covering Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire) and the North East Mayoral Combined Authority were established in May 2024.

In September 2024, mayoral combined authorities were approved for Greater Lincolnshire and Hull and East Yorkshire with mayors for these authorities expected to be elected in May 2025. Non-mayoral combined authorities were also agreed for Devon and Torbay and Lancashire.[5]

As of October 2024, in addition to the Greater London Authority there are 11 mayoral Combined Authorities in England. There are additional proposals for more combined authorities to be established in the future.[6]

Mayoral Council for England

In 2012, prime minister David Cameron had proposed that directly elected mayors sit within a "Cabinet of Mayors" giving them the opportunity to share ideas and represent their regions at national level. The cabinet of mayors would be chaired by the prime minister and would meet at least twice a year.[7][8]

In 2022, Labour also proposed a similar body to be known as the "Council of England", chaired by the prime minister, to bring together combined authority mayors, representatives of local government and other stakeholders.[9]

In 2024, the new Labour government established a UK-wide Council of the Nations and Regions including the Prime Minister, the First Ministers of Scotland and Wales, the First and deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland, the Mayor of London and the Mayors of Combined Authorities, and an England only Mayoral Council including ministers from the UK government and Mayors of England's Combined Authorities.[10] As the Labour government hopes that combined authorities will be established throughout England, the Mayoral Council would enventually evolve into an all England forum.[11] As of October 2024, 48% of the population and 26% of the land area of England is represented on the Mayoral Council.[12]

'England only' departments of the British Government

"England-only" policy areas

The UK central government retains the following powers in relation to England which are exercised by devolved governments in the rest of the United Kingdom:[13]

- Agriculture

- Culture

- Education

- Environment

- Health (including social care)

- Housing

- Local government

- Road transport (including buses, cycling and local transport)

- Sport

- Tourism

Ministerial departments

Several ministerial government departments, non-ministerial government departments, executive agencies and non-departmental public bodies of the UK government have responsibilities for matters affecting England alone.[14]

- Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government.

- Department for Education

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra)

- Department of Health and Social Care

The following ministerial departments deal mainly with matters affecting England though they also have some UK-wide responsibilities in certain areas;

Non-ministerial departments

- Forestry Commission

- Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills (Ofsted)

- Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual)

Executive agencies

- Active Travel England

- Education and Skills Funding Agency

- Health Security Agency

- Planning Inspectorate

- Rural Payments Agency

- Standards and Testing Agency

- Teaching Regulation Agency

Non-departmental public bodies

- Arts Council England

- Care Quality Commission

- Children's Commissioner for England

- Environment Agency

- Forestry England

- Historic England

- Homes England

- Natural England

- NHS England

- NHS Resolution

- Office for Students

- Office of the Schools Adjudicator

- Regulator of Social Housing

- School Teachers' Review Body

- Skills England

- Social Work England

- Sport England

- VisitEngland

Tribunals

Ombudsman

Government owned companies

- Community Health Partnerships

- Genomics England

- National Highways

- NHS Property Services

- NHS Professionals

- NHS Shared Business Services

Local government

London borough or the City of London

Unitary authority

Two-tier non-metropolitan county

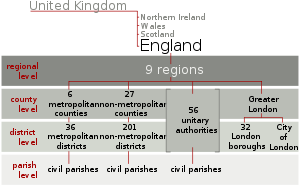

For the purposes of local government, England is divided into as many as four levels of administrative divisions. At some levels, various legislation has created alternative types of administrative division.

Districts in England may also have the status of borough, city or royal borough.

The metropolitan counties were divided into metropolitan districts which are usually called boroughs. When the county councils were abolished the metropolitan districts gained much of their powers and therefore function similar to other unitary authorities.

Shire counties are divided into non-metropolitan districts. Power is shared with the county council, but shared differently from the metropolitan counties when first created.

The civil parish is the most local unit of government in England. Under the legislation that created Greater London, they are not permitted within its boundary. Not all of the rest of England is parished, though the number of parishes and total area parished is growing.

Political parties

The Green Party of England and Wales had an amicable split from Scottish counterpart in 1990, and the Wales Green Party section is semi-autonomous.

The Conservative Party adopted a policy of English Votes on English Legislation (EVoEL), to prevent non-English constituency MPs voting on exclusively English legislation. Despite 'One Nation' Conservativism, some have flirted[15] with devolution factors like the Barnett-Formula.

The Labour Party have devolved sub-parties for Scotland and Wales. Labour tried unsuccessfully to devolve power to the Regions of England, on the basis of England being dis-proportionately large as a single entity within the United Kingdom. Lord Falconer, a Scottish peer claimed a devolved English parliament would dwarf the rest of the United Kingdom.[16]

The Liberal Democrats have nominally separate Scottish, Welsh and English parties.

In spite of seeking independence of the United Kingdom from the European Union, both the UK Independence Party (UKIP) and Reform UK do not support further onward devolution to England, although support scrapping the Barnett formula.

Minor political parties

Most of the parties that only operate within England alone tend to be purely interested in English issues, like English independence or an English Parliament. Examples include the English Democrats, One England, the English People's Party, the English Radical Alliance, the England First Party, and the English Independence Party.

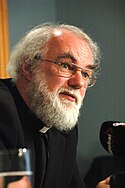

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church[17] in England. King Charles III is the official head of the church, with the title Supreme Governor of the Church of England, while the Archbishop of Canterbury is the head clergyman. The canon law of the Church of England states, "We acknowledge that the King's most excellent Majesty, acting according to the laws of the realm, is the highest power under God in this kingdom, and has supreme authority over all persons in all causes, as well ecclesiastical as civil." In practice this power is often exercised through Parliament and the Prime Minister.

Of the forty-four diocesan archbishops and bishops in the Church of England, twenty-six are permitted to sit in the House of Lords. The Archbishops of Canterbury and York automatically have seats, as do the Bishops of London, Durham and Winchester. The remaining twenty-one seats are filled in order of seniority by consecration. It may take a diocesan bishop a number of years to reach the House of Lords, at which point he becomes a Lord Spiritual.[18]

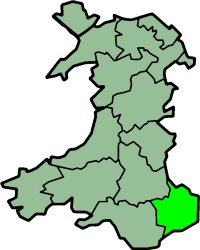

Monmouthshire

The historic county of Monmouthshire, lying in the Welsh Marches (the Anglo-Welsh border), is a bone of contention for some English nationalists.[19] Although the county is now mostly in Wales, to add to the confusion, Welsh Bicknor was an exclave of the county, and is in Herefordshire (England). The Welsh Border has historically been more fluid than the Anglo-Scottish border

Monmouthshire's Welsh status was ambiguous until relatively recently, with it often thought of as part of England. The entirety of Wales was made part of the Kingdom of England by the Statute of Rhuddlan, but did not adopt the same civil governance system, with the area of Monmouthshire being under the control of Marcher Lords.

The Laws in Wales Act 1535 integrated Wales directly into the English legal system and the "Lordships Marchers within the said Country or Dominion of Wales" were allocated to existing and new shires. Some lordships were annexed to existing counties in England and some were annexed to existing counties in Wales, with the remainder being divided up into new counties. Despite Monmouthshire being a new county, it was given two Knights of the Shire in common with existing counties in England, rather than one as in the counties in Wales.

The relevant section of the Act states that "one Knight shall be chosen and elected to the same Parliaments for every of the Shires of Brecknock, Radnor, Montgomery and Denbigh, and for every other Shire within the said Country of Dominion of Wales". As Monmouthshire was dealt with separately it cannot be taken to be a shire "within the said Country of Dominion of Wales". The Laws in Wales Act 1542 specifically enumerates the Welsh counties as twelve in number, excluding Monmouthshire from the count.

The issue was finally clarified in law by the Local Government Act 1972, which provided that "in every act passed on or after 1 April 1974, and in every instrument made on or after that date under any enactment (whether before, on or after that date) "Wales", subject to any alterations of boundaries..." included "the administrative county of Monmouthshire and the county borough of Newport".[20] The name passed onto a district of Gwent between 1974 and 1996, and on 1 April 1996, a local government principal area named Monmouthshire, covering the eastern 60% of the historic county, was created.

However, the issue has not gone completely away, and the English Democrats nominated candidates for the 2007 Welsh Assembly elections in three of six constituencies in the area of the historic county with a view to promoting a referendum on 'Letting Monmouthshire Decide' whether it wished to be part of Wales or England.[21] The party received between 2.2% and 2.7% of the vote (a much lower total than Plaid Cymru) and failed to have any members elected.[22]

Berwick-upon-Tweed

The status of Berwick, north of the River Tweed is controversial, especially amongst Scottish nationalists.[23] Berwick remained a county in its own right until 1885, when it was included in Northumberland for Parliamentary purposes. The Interpretation Act 1978 provides that in legislation passed between 1967 and 1974, "a reference to England includes Berwick upon Tweed and Monmouthshire".

In 2008, SNP MSP Christine Grahame made calls in the Scottish Parliament for Berwick to become part of Scotland again, saying

- "Even the Berwick-upon-Tweed Borough Council leader, who is a Liberal Democrat, backs the idea and others see the merits of reunification with Scotland."[24]

However, Alan Beith, the Liberal Democrat MP for Berwick, said the move would require a massive legal upheaval and is not realistic.[25] However he is contradicted by another member of his party, the Liberal Democrat MSP Jeremy Purvis, who was born and brought up in Berwick. Purvis has asked for the border to be moved twenty miles south (i.e., south of the Tweed) to include Berwick borough council rather than just the town, and has said:

- "There's a strong feeling that Berwick should be in Scotland, Until recently, I had a gran in Berwick and another in Kelso, and they could see that there were better public services in Scotland. Berwick as a borough council is going to be abolished and it would then be run from Morpeth, more than 30 miles away.".[26]

According to a poll conducted by a TV company, 60% of residents favoured Berwick rejoining Scotland.[27]

Cornwall

Most English people and the UK government regard Cornwall as a county of England, but Cornish nationalists believe that the Duchy of Cornwall has a status deserving greater autonomy. Campaigners including Mebyon Kernow, a Cornish nationalist party, and all five Cornish Liberal Democrat MPs opposed participation in the South West Regional Assembly alongside Devon, Dorset, Gloucestershire, Somerset and Wiltshire in favour of a democratically elected Cornish Assembly.[28][29][30]

See also

Sources

Footnotes

- ^ C.Warren Hollister, The Making of England, 55 B.C. to 1399 (7th ed. 1996) p 82

- ^ "English vote plan to become law despite objections". BBC News. 22 October 2015.

- ^ "Commons scraps English votes for English laws". BBC News. 13 July 2021.

- ^ eGov monitor – Planning transfer undermines democracy Archived 19 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine. 29 November 2007

- ^ "Four devolution agreements signed off and others progressing".

- ^ (1) Henderson (2) Paun, (1) Duncan (2) Akash (6 March 2023). "English Devolution". Institute for Government.

{cite web}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Mayoral referendums: The mayors of the twinned cities". BBC News. 19 April 2012.

- ^ "Rival campaigns fight over directly-elected mayors in England". BBC News. 12 April 2012.

- ^ A New Britain: Renewing our Democracy and Rebuilding our Economy (PDF). Labour Party (Report). December 2022.

- ^ "Serving the country".

- ^ White, Hannah; Thomas, Alex; Tetlow, Gemma; Pope, Thomas; Davies, Nick; Davison, Nehal; Metcalfe, Sophie; Paun, Akash (26 September 2024). "Seven things we learned from the Labour Party Conference 2024". Institute for Government. Archived from the original on 2 October 2024. Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ "English devolution". Institute for Government. 21 June 2024.

- ^ https://www.bennettinstitute.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Devolving-English-Government.pdf

- ^ Newman, Jack; Kenny, Michael (April 2023). Devolving English government (PDF). Bennett Institute for Public Policy (Report). Cambridge University.

- ^ Settle, Michael (30 June 2019). "Johnson accused of 'dubious U-turn' after saying he would keep funding formula he previously criticised". The herald.

- ^ "No English parliament – Falconer". BBC News. 10 March 2006. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- ^ "The History of the Church of England". The Archbishops' Council of the Church of England. Archived from the original on 21 February 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2006.

- ^ House of Lords: alphabetical list of Members Archived 2 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 12 December 2008.

- ^ "Monmouth Web Community - History - Wales". Archived from the original on 4 February 2005.

- ^ Local government Act 1972 (c.70), sections 1, 20 and 269

- ^ "English Democrats Party Campaigning for an English Parliament". Archived from the original on 7 August 2018.

- ^ "Election 2007 | Welsh Assembly | Election Result: Wales". BBC NEWS. 7 May 2007. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022.

- ^ Kerr, Rachel (8 October 2004). "A tale of one town". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012.

- ^ "'Return to fold' call for Berwick". BBC News. 10 February 2008. Archived from the original on 1 May 2023.

- ^ Hamilton, Alan (13 February 2008). "Berwick thinks it's time to change sides ... again". The Times. London. Retrieved 14 February 2008.[dead link]

- ^ The Sunday Post, 10 February 2008, Scots plan to capture 20 miles of England

- ^ TV poll backs Berwick border move BBC News, 17 February 2008

- ^ "George Takes Cornish Assembly Campaign to Downing Street". Andrew George. 12 December 2001. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ "Blair gets Cornish assembly call". BBC News. 11 December 2001.

- ^ "Motion To Cornwall Liberal Democrats' Conference". Andrew George. 12 November 2005. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

References

- Dicey & Morris (1993). The Conflict of Laws. Sweet & Maxwell. ISBN 0-420-48280-6.