Ethiopian Christianity

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 62,600,000 (2020)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Tigray (96.1%), Gambela (90.3%), Addis Ababa (83%), Amhara (82.7%), SNNP (77.8%), Oromia (48.7%), Benishangul-Gumuz (46.5%)[2] | |

| Religions | |

| Ethiopian Orthodoxy (43.5%), P'ent'ay (Protestantism) (18.6%), Catholic (0.7%) |

| Christianity by country |

|---|

|

|

|

Christianity in Ethiopia is the country's largest religion with members making up 68% of the population.[3]

Christianity in Ethiopia dates back to the ancient Kingdom of Aksum, when the King Ezana first adopted the faith in the 4th century AD. This makes Ethiopia one of the first regions in the world to officially adopt Christianity.[4][5]

Various Christian denominations are now followed in the country. Of these, the largest and oldest is the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, an Oriental Orthodox church centered in Ethiopia. The Orthodox Tewahedo Church was part of the Coptic Orthodox Church until 1959 when it was granted its own patriarch by the Coptic Orthodox Pope of Alexandria and Patriarch of All Africa Cyril VI.

Religion in Ethiopia (2020)[6]

Religion in Ethiopia with breakdown of Christian denominations (2007)[7]

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church is one of the largest original and oldest Christian churches in Africa; only surpassed in age by the Church of the East, the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Greek Orthodox Church, and the Coptic Church of Egypt. It has a membership of 32 to 36 million,[8][9][10][11] the majority of whom live in Ethiopia,[12] and is thus the largest of all Oriental Orthodox churches. Next in size are the various Protestant congregations, who include 13.7 million Ethiopians. The largest Protestant group is the Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus, with about 5 million members. Catholicism has been present in Ethiopia since the nineteenth century, and numbers over 530,000 believers as of the 2007 census. In total, Christians make up about 63% of the total population of the country.[13]

Spread of Christianity

Before the fourth century, a mixture of religions existed in Ethiopia, with parts of the population adhering to a religion that worshiped the serpent-king Arwe, and others adhering to what scholars call "a Judaized form of religion".[14]

Although Christianity existed in the region long before the rule of King Ezana of Aksum, the religion took a strong foothold when it was declared a state religion in 330 AD.

Rufinus of Tyre, a church historian, recorded a personal account as did other Church historians such as Socrates of Constantinople and Sozomen. The Garima Gospels are thought to be the world's oldest surviving illuminated Christian manuscripts.

Frumentius

Frumentius, a Phoenician Christian, was a slave to the Ethiopian king and there is evidence Judaism was in the land before his arrival (mythically due to King Solomon of Israel). After being shipwrecked and captured at an early age, Frumentius was carried to Aksum, where he was treated well with his companion Edesius. At the time, there was a small population of West Asian Christians living in Aksum who sought refuge from Roman persecution. Once of age, Frumentius and Edesius were allowed to return to their homelands, however they chose to stay at the request of the queen. In doing so, they began to secretly promote Christianity through the lands.[15][unreliable source?]

During a trip to meet with church elders, Frumentius met with Athanasius, Pope of Alexandria. After recommending that a bishop be sent to proselytize, a council decided that Frumentius be appointed as a bishop for Ethiopia.

By 331 AD, Frumentius returned to Ethiopia, he was welcomed with open arms by the rulers who were at the time 'not' Christian. Ten years later, through the support of the kings, the majority of the kingdom was converted and Christianity was declared the official state religion.[16]

Spread of Christianity in Ethiopia

The Syriac Nine Saints and Sadqan missionaries expanded Christianity far beyond the caravan routes and the royal court through monastic communities and missionary settlements from which Christianity was taught. The efforts of these Eastern Rite Syriac missionaries from Assyria (Mesopotamia and south east Anatolia), Asia Minor and Aramea (Syria) facilitated the Church’s expansion deep into the interior and caused friction with the traditions of the local people. The Syriac Christian missions also served as permanent centers of Christian learning in which Syriac speaking monks finally began to translate the Bible and other religious texts from Greek and Aramaic into Ethiopic so that their Ethiopian converts could actually read Scripture. These translations were vital to the spread of Christianity, no longer a religion for the small percentage of Ethiopians who could read Greek or Aramaic/Syriac, throughout Ethiopia.[17]

With the translation of Scripture into Ethiopic allowing for common people to learn about Christianity, many of the local people joined the Syriac Christian missions and monasteries, received religious training through monastic rule based around communalism, hard work, discipline, obedience, and asceticism, and caused the growth of the Church’s influence, especially among young people who were attracted to the mystical aspects of the religion. Newly trained Ethiopian ministers opened their own schools in their parishes and offered to educate members of their congregations. Ethiopian kings encouraged this development because it gave more prestige to the Ethiopian clergy, attracting even more people to join, which allowed the Church to grow beyond its origins as a royal cult to a widespread religion with a strong position in the country.

By the beginning of the sixth century, there were Christian Churches throughout northern Ethiopia. King Kaleb, of the Aksumite Kingdom, led crusades against Christian persecutors in southern Arabia, where Judaism was experiencing a resurgence that led to the persecution of Christians. King Kaleb’s reign is also significant for the spread of Christianity among the Agaw tribes of central Ethiopia.

In the late 16th century Christianity spread among petty kingdoms in Ethiopia's west, like Ennarea, Kaffa or Garo.

Christianity has also spread among Muslims. A 2015 study estimated some 400,000 Christians from a Muslim background in the country, most of them Protestants of some form.[18]

Alexandria and the early Aksumite Church

During the 6th century, the Patriarchate of Alexandria encouraged clerical immigration to Aksum and a program of careful recruitment of religious leaders in the kingdom to ensure that the rich and valuable diocese of Aksum remained under the control of the Alexandrian patriarchate. The kings and bishops who encouraged these settlements assigned missionaries to appropriate areas in Aksum. They donated money to communities and religious schools while protecting their occupants from local anti-Christians. Students of the schools were recruited, ordained, and sent to work in parishes in new Christian areas. There is little evidence about the activities of the daily life of the early Aksumite Church, but it is clear that the essential doctrinal and liturgical traditions were established in the first four centuries of its creation. The strength of these traditions was the main driving force behind the Church’s survival despite its distance from its patriarch in Alexandria.

Judaism, Christianity, and the Solomonic Dynasty

The Kebra Nagast is considered Holy Scripture in Ethiopia and is available in print.[1]

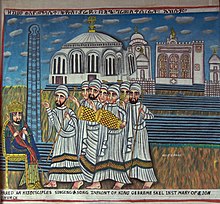

The Solomonic Dynasty’s legendary origins come from an Ethiopian account called the Kebre Negast. According to the story, Queen Makeda, who took the Ethiopian throne in the 10th century, B.C., traveled to Jerusalem to learn to be a good ruler from King Solomon, who was famous worldwide for his wisdom and capabilities as a ruler. King Solomon agreed to take Makeda as his student and taught her how to be a good queen. Queen Makeda was so impressed with Solomon that she converted to Judaism and provided Solomon with many gifts. Before Makeda returned home, the two had a son together. Solomon had a dream in which God said that his and Makeda’s son would be the head of a new order. In response, he sent Makeda home but told her to send their son back to Jerusalem when he came of age to be taught Jewish lore and law. Makeda did as she was told and sent Menilek I, their son, to Jerusalem to be taught by Solomon, who offered to make him the prince of Jerusalem. However, Menilek declined and instead returned to Ethiopia, anointed by his father and God to be the king of Ethiopia.

The Kebre Negast exemplifies the importance of Judaism, and subsequently, of Christianity to the Ethiopian people, serving as a source of Ethiopian national pride and providing a justification for the idea of Ethiopians as a chosen people of God. More importantly to the Solomonic Dynasty however, it provided the grounds for the “restored Solomonic” Empire, so named because of its renewed fervor for the connection of King Solomon to Ethiopian royalty, which began under Emperor Yekuno Amlak (r. 1270-1285) and was ruled and justified by Christianity until the late twentieth century.

By the time that Amda Siyon (r. 1314-1344) took the throne in 1314, Sabradin of Ifat led a united Muslim front made up of people angered by Christian rule, destroying churches in Ethiopia and forcing Christians to convert to Islam. Siyon responded with a savage attack that resulted in the defeat of Yifat. Furthermore, Siyon's victory caused the frontier of Christian power in Africa to expand past the Awash Valley.

The Yafit defeat allowed Alexandria to send Abuna Yaqob, to Ethiopia in 1337 to be its metropolitan. Yakob reinvigorated the Ethiopian Church, which had been without a leader for almost 70 years, by ordaining new clergy and consecrating long-standing churches that had been built during the power void. Furthermore, Yaqob deployed a corps of monks into the newly obtained lands. These monks were often killed or injured by the conquered people, but, through hard work, faith, and promises that local elites could keep their positions through conversion, the new territories were converted to Christianity.

The Sabbatarian controversy

One of the more fervent monks appointed by Abuna Yakob was Abba Ewostatewos (c. 1273–1352). Ewostatewos designed a monastic ideology stressing the necessity for isolation from state influences. He insisted that the people and the Church return to the teachings of the Bible. Ewostatewos’s followers were called Ewostathians or Sabbatarians, due to their emphasis on observing the Sabbath on Saturday.

The Ewostathians retreated into remote northeastern Ethiopia to escape religious persecution.[19] Over time, however, the Sabbatarians engaged in missionary activities that successfully converted adjacent non-Christian communities and, within a few generations, Ewostathian monasteries and communities spread throughout the Eritrean highlands.

The spread of Ewostathianism alarmed the Ethiopian establishment who still considered them to be dangerous due to their refusal to follow state authorities. In response, in 1400, Emperor Dawit I (r. 1380–1412) invited the Sabbatarians to come to court and participate in a debate. Abba Filipos led the Ewostathian delegation, which argued their case with passion, refusing to repudiate the Sabbath, until the Ethiopian bishop ordered that the delegation be arrested. The goal of the arrests was to kill Ewostathianism by removing its leaders, but its localized nature allowed it to survive, and, as a result, the arrest of the Ewostathians only led to a rift in the Ethiopian Church, between the ruling class’s traditional Christianity and what was becoming a large movement of Ewostathian Christians.

Ewostathianism enjoyed impressive growth in the first half of the 15th century. This growth was noticed by Dawit's successor, Emperor Zara Yakob (r. 1434-1468) who realized that the energy of the Sabbatarians could be useful in reinvigorating the church and promoting national unity. The Church, when Yakob took the throne, was widespread, but the consequence of so many different peoples being part of the same church was that there were often many different messages spread throughout the empire, as the clergy was split between followers of Alexandria and Ewostathians, who refused to follow the hierarchy of Alexandria.

Emperor Yakob called for a compromise in 1436, meeting with two bishops, Mikail and Gabriel, sent by the sea of St. Mark. Yakob convinced the bishops that if Alexandria agreed to accept the Ewostathian view of the Sabbath, then the Ewostathians would agree to recognize Alexandrian authority. Next, Yakob traveled to Aksum for his coronation, remaining there until 1439 and reconciling with the Sabbatarians, who agreed to pay feudal dues to the emperor.

In 1450, the conflict officially came to an end, as Mikail and Gabriel agreed to recognize the Sabatarians' observance of the Sabbath,[20] and the Sabbatarians agreed to adopt the sacrament of Holy Orders, which they had previously considered to be illegitimate due to its dependence on the authority of the church in Alexandria.

Isolation as a Christian nation

With the emergence of Islam in the 7th century, Ethiopia's Christians became isolated from the rest of the Christian world. The head of the Ethiopian church has been appointed by the patriarch of the Coptic church in Egypt, and Ethiopian monks had certain rights in the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Ethiopia was the only region of Africa to survive the expansion of Islam as a Christian state.[21]

Jesuit missionaries

In 1441 some Ethiopian monks traveled from Jerusalem to attend the Council in Florence which discussed possible union between the Catholic and Greek Orthodox churches. [citation needed]

The arrival of the Christian monks caused something of a sensation. It began two centuries of contact in which there were hopes to bring the Ethiopians into the Catholic fold (the doctrinal problem was that they inclined to miaphysitism (considered a heresy by the Catholics) associated with the Coptic church of Egypt). In 1554 Jesuits arrived in Ethiopia to be joined in 1603 by Pedro Páez, a Spanish missionary of such energy and zeal that he has been called the second apostle of Ethiopia (Frumentius being the first). The Jesuits were expelled in 1633 which was then followed by two centuries of more isolation until the second half of the 19th century.[21][unreliable source?]

Orthodox Tewahedo

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church dates back to the introduction of Christianity to the country in 330,[22] and in 2022 it has between 36 million and 49.8 million adherents in Ethiopia.[23]

P'ent'ay (Ethiopian-Eritrean Evangelicalism)

Catholicism

See also

- Ethiopian chant

- Religion in Ethiopia

- Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

- Ethiopian Catholic Church

- Catholic Church in Ethiopia

- Protestantism in Ethiopia

- P'ent'ay

- Ethio-SPaRe

References

- ^ "Religious Composition by Country, 2010-2050". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 2015-04-02.

- ^ "2007 Ethiopian census, first draft" (PDF). Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ The ARDA website, retrieved 2023-08-03

- ^ "Ethiopia". CIA World Factbook. December 2, 2022.

- ^ Kahsay, Semhal (May 26, 2020). "The Largest Religions in Ethiopia". YEG Daily.

- ^ World Religion Database 2020 at the ARDA website, retrieved 2023-08-03

- ^ 2007 Ethiopian census, first draft, Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency (accessed 6 May 2009)

- ^ "Orthodox Christianity in the 21st Century". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 8 November 2017.

Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church has an estimated 36 million adherents, nearly 14% of the world's total Orthodox population.

- ^ Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Population Census Commission (4 June 2012). "Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census Results" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2012.

Orthodox 32,138,126

- ^ "Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church | church, Ethiopia". Encyclopedia Britannica.

In the early 21st century the church claimed more than 30 million adherents in Ethiopia.

- ^ "Ethiopia: An outlier in the Orthodox Christian world". Pew Research Center.

- ^ Berhanu Abegaz, "Ethiopia: A Model Nation of Minorities" (accessed 6 April 2006)

- ^ Numbers for all groups except the Mekane Yesus are taken from the 2007 Ethiopian census, Table 3.3 Population by Religion, Sex, and Five Year Age Groups: 2007 Archived November 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hammerschmidt, Ernst (1965). "Jewish Elements in the Cult of the Ethiopian Church". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 1 (2): 1–12. JSTOR 41965723.

- ^ "Christianity in Ethiopia". EthiopiaFamine.com. Archived from the original on 2010-03-29. Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- ^ Hansberry, William Leo. Pillars in Ethiopian History; the William Leo Hansberry African History Notebook. Washington: Howard University Press, 1974.

- ^ Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), pp. 23-25

- ^ Johnstone, Patrick; Miller, Duane Alexander (2015). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". IJRR. 11: 14. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ Brook, Kevin Alan (27 September 2006). The Jews of Khazaria. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 266. ISBN 978-1-4422-0302-0

- ^ Binns, John (28 November 2016). The Orthodox Church of Ethiopia: A History. I.B.Tauris. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-78672-037-5.

- ^ a b "HISTORY OF ETHIOPIA". HistoryWorld.

- ^ Moore, Dale H. (1936). "Christianity in Ethiopia". Church History. 5 (3): 271–284. doi:10.2307/3160789. ISSN 0009-6407. JSTOR 3160789. S2CID 162029676.

- ^ "Ethiopia". The World Factbook. 12 September 2022. Retrieved 2022-09-16.

Population 113,656,596 (2022 est.)… Ethiopian Orthodox 43.8%

Sources

- Grillmeier, Aloys; Hainthaler, Theresia (1996). Christ in Christian Tradition: The Church of Alexandria with Nubia and Ethiopia after 451. Vol. 2/4. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22300-7.

- Marcus, Harold G. A History of Ethiopia. Berkeley: U of California, 1994. Print.

- Munro-Hay, Stuart. Ethiopia the Unknown Land: A Cultural and Historical Guide. London: I.B. Tauris, 2002. Print.

- Tamrat, Tardesse. Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270-1527. Oxford: Clarendon, 1972. Print.

External links

Media related to Christianity in Ethiopia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Christianity in Ethiopia at Wikimedia Commons