Eurovision Song Contest 1992

| Eurovision Song Contest 1992 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Dates | |

| Final | 9 May 1992 |

| Host | |

| Venue | Malmö Isstadion Malmö, Sweden |

| Presenter(s) | Lydia Capolicchio Harald Treutiger |

| Musical director | Anders Berglund |

| Directed by | Kåge Gimtell |

| Executive supervisor | Frank Naef |

| Host broadcaster | Sveriges Television (SVT) |

| Website | eurovision |

| Participants | |

| Number of entries | 23 |

| Debuting countries | None |

| Returning countries | |

| Non-returning countries | None |

| |

| Vote | |

| Voting system | Each country awarded 12, 10, 8-1 point(s) to their 10 favourite songs |

| Winning song | "Why Me" |

The Eurovision Song Contest 1992 was the 37th edition of the Eurovision Song Contest, held on 9 May 1992 at the Malmö Isstadion in Malmö, Sweden. Organised by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) and host broadcaster Sveriges Television (SVT), and presented by Lydia Capolicchio and Harald Treutiger, the contest was held in Sweden following the country's victory at the 1991 contest with the song "Fångad av en stormvind" by Carola.

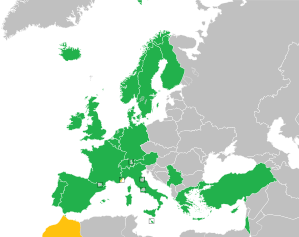

Twenty-three countries participated in the contest – a new record number of participating countries – with the Netherlands returning to the contest following a one-year break to join the twenty-two countries which had participated in the previous year's event.

The winner was Ireland with the song "Why Me", written by Johnny Logan and performed by Linda Martin. This marked Ireland's fourth contest win, and brought songwriter Logan his third win overall, having previously won the contest in 1980 as singer and in 1987 as both singer and songwriter. The United Kingdom, Malta, Italy, and Greece also placed in the top five, with the United Kingdom recording its thirteenth second-place position and Malta and Greece achieving their best ever results in the contest.

Location

The 1992 contest took place in Malmö, Sweden, following the country's victory at the 1991 contest with the song "Fångad av en stormvind", performed by Carola. It was the third time that Sweden had hosted the contest, following the 1975 and 1985 events held in Stockholm and Gothenburg respectively.[1] The chosen venue was the Malmö Isstadion, an indoor ice hockey arena constructed in 1970, the former home stadium of the Malmö Redhawks ice hockey team and which had also previously hosted concerts by Frank Sinatra and Julio Iglesias amongst others.[2][3][4][5] With a typical capacity of 5,800 spectators for ice hockey matches, for the contest an audience of around 3,700 was present.[2][3]

Participating countries

With the Netherlands making a return to the contest after missing the previous year's contest, and Malta continuing to participate following its return to the event in 1991, twenty-three countries in total competed in the 1992 contest – a new contest record.[6] Ahead of the 1991 event the Maltese broadcaster had been told by the contest organisers that they would only be allowed to remain in the competition if another nation dropped out of the event, however after placing sixth in the 1991 contest, the organisers instead decided to raise the maximum number of participating countries to twenty-three to make space for continued Maltese participation.[2][7] Yugoslavia's entry represented the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia for the first and only time, following the break-up of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in the past year which had been responsible for all previous Yugoslav entries; following the 1992 contest Yugoslavia was excluded from participating and the nation would not return to the contest until 2004, when it competed under its new name Serbia and Montenegro.[8][9] Of all the countries that had ever participated in the contest, Monaco and Morocco were the only ones absent from this year's event.[5]

Among the competing entries at this year's contest was the first entry to be performed in a French Creole language, and the first appearance of a song performed in Luxembourgish since 1960.[10][11]

The 1992 event featured a number of artists who had competed in previous editions: Sigríður Beinteinsdóttir and Grétar Örvarsson, two members of Iceland's entrant Heart 2 Heart, had previously represented the country in 1990 as Stjórnin; Rom Heck, a member of the group Kontinent that represented Luxembourg alongside Marion Welter, had previously competed in the 1989 contest as a member of the group Park Café; Linda Martin made a second contest appearance for Ireland following the 1984 contest; Mia Martini also competed for the second time for Italy, after previously participating in 1977; and the group Wind represented Germany for the third time, following their previous entries in 1985 and 1987.[10][12] Additionally, Cyprus's Evridiki participated as lead artist after previously performing backing vocals for the Cypriot entries in 1983, 1986 and 1987.[13]

| Country | Broadcaster | Artist | Song | Language | Songwriter(s) | Conductor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF | Tony Wegas | "Zusammen geh'n" | German | Leon Ives | ||

| RTBF | Morgane | "Nous on veut des violons" | French |

|

Frank Fievez | |

| CyBC | Evridiki | "Teriazoume" (Ταιριάζουμε) | Greek | George Theofanous | George Theofanous | |

| DR | Lotte Nilsson and Kenny Lübcke | "Alt det som ingen ser" | Danish | Carsten Warming | Henrik Krogsgaard | |

| YLE | Pave | "Yamma Yamma" | Finnish | Olli Ahvenlahti | ||

| Antenne 2 | Kali | "Monté la riviè" | French, Antillean Creole |

|

Magdi Vasco Noverraz | |

| MDR[a] | Wind | "Träume sind für alle da" | German | Norbert Daum | ||

| ERT | Cleopatra | "Olou tou kosmou i elpida" (Όλου του κόσμου η ελπίδα) | Greek | Christos Lagos | Haris Andreadis | |

| RÚV | Heart 2 Heart | "Nei eða já" | Icelandic |

|

Nigel Wright | |

| RTÉ | Linda Martin | "Why Me" | English | Noel Kelehan | ||

| IBA | Dafna | "Ze Rak Sport" (זה רק ספורט) | Hebrew | Kobi Oshrat | ||

| RAI | Mia Martini | "Rapsodia" | Italian |

|

Marco Falagiani | |

| CLT | Marion Welter and Kontinent | "Sou fräi" | Luxembourgish |

|

Christian Jacob | |

| PBS | Mary Spiteri | "Little Child" | English |

|

Paul Abela | |

| NOS | Humphrey Campbell | "Wijs me de weg" | Dutch | Edwin Schimscheimer | Harry van Hoof | |

| NRK | Merethe Trøan | "Visjoner" | Norwegian |

|

Rolf Løvland | |

| RTP | Dina | "Amor d'água fresca" | Portuguese | Carlos Alberto Moniz | ||

| TVE | Serafín | "Todo esto es la música" | Spanish |

|

Javier Losada | |

| SVT | Christer Björkman | "I morgon är en annan dag" | Swedish | Niklas Strömstedt | Anders Berglund | |

| SRG SSR | Daisy Auvray | "Mister Music Man" | French | Gordon Dent | Roby Seidel | |

| TRT | Aylin Vatankoş | "Yaz Bitti" | Turkish |

|

Aydın Özarı | |

| BBC | Michael Ball | "One Step Out of Time" | English |

|

Ronnie Hazlehurst | |

| JRT | Extra Nena | "Ljubim te pesmama" (Љубим те песмама) | Serbian |

|

Anders Berglund |

Production and format

The Eurovision Song Contest 1992 was produced by the Swedish public broadcaster Sveriges Television (SVT). Ingvar Ernblad served as executive producer, Kåge Gimtell served as producer and director, Göran Arfs served as designer, and Anders Berglund served as musical director leading an assembled orchestra of around 50 musicians.[6][17][18] A separate musical director could be nominated by each country to lead the orchestra during their performance, with the host musical director also available to conduct for those countries which did not nominate their own conductor.[10]

Each participating broadcaster submitted one song, which was required to be no longer than three minutes in duration and performed in the language, or one of the languages, of the country which it represented.[19][20] A maximum of six performers were allowed on stage during each country's performance, and all participants were required to have reached the age of 16 in the year of the contest.[19][21] Each entry could utilise all or part of the live orchestra and could use instrumental-only backing tracks, however any backing tracks used could only include the sound of instruments featured on stage being mimed by the performers.[21][22]

Following the confirmation of the twenty-three competing countries, the draw to determine the running order was held on 3 December 1991 and was conducted by Carola.[2]

The results of the 1992 contest were determined through the same scoring system as had first been introduced in 1975: each country awarded twelve points to its favourite entry, followed by ten points to its second favourite, and then awarded points in decreasing value from eight to one for the remaining songs which featured in the country's top ten, with countries unable to vote for their own entry.[23] The points awarded by each country were determined by an assembled jury of sixteen individuals, which was required to be split evenly between members of the public and music professionals, between men and women, and by age. Each jury member voted in secret and awarded between one and ten votes to each participating song, excluding that from their own country and with no abstentions permitted. The votes of each member were collected following the country's performance and then tallied by the non-voting jury chairperson to determine the points to be awarded. In any cases where two or more songs in the top ten received the same number of votes, a show of hands by all jury members was used to determine the final placing.[24][25]

The stage design for the Malmö contest centred around a large representation of the bow of a Viking ship, flanked on either side by sets of stairs, while a hexagonal design was used for the floor area in front which was painted to resemble the Eurovision network logo.[6][11] To the left of the stage as seen by the audience sat the orchestra, while to the right stood a large video wall and a smaller stage for use by the presenters to introduce each act and during the voting sequence. Behind the Viking ship the backdrop featured a representation using neon lighting of the span of the Öresund Bridge, the construction of which had yet to begin but which would connect Sweden and Denmark, and thus Sweden and the European mainland, from 1999.[11][26][27]

Rehearsals in the contest venue began on 3 May 1992, focussing on the opening performances and interval act. The participating artists began their rehearsals on 4 May, and each participating delegation was afforded two technical rehearsals in the week of the contest, with countries rehearsing in the order in which they would perform. The first rehearsals, held on 4 and 5 May, saw each country given a 40-minute slot on stage, followed by a press conference. Each delegation was then given a second slot to rehearse on stage, this time for 30 minutes, on 6 and 7 May. Three dress rehearsals were held with all artists, two held in the afternoon and evening of 8 May and one final rehearsal in the afternoon of 9 May. Audiences were present for the latter two dress rehearsals, and the final afternoon dress rehearsal was also recorded for use as a production stand-by. During the contest week the participating delegations were also invited to a welcome reception, which was held in Malmö rådhus.[2]

This year's contest featured a mascot: the "Eurobird", an anthropomorphic bird, featured as a computer animated character during the transition between the competing songs.[26][28]

Contest overview

The contest took place on 9 May 1992 at 21:00 (CEST) with a duration of 3 hours. The show was presented by the Swedish journalists and television presenters Lydia Capolicchio and Harald Treutiger.[6][10]

The opening sequence featured a computer-generated animation showing the journey from the previous year's host city Rome to Malmö, including oversized models placed on the European continent representing the Colosseum, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the Alps, the Eiffel Tower, and structures in Malmö including Malmö Castle, Kronprinsen and the Hyllie Water Tower.[11][26] This was followed by performances within the venue by the Malmöflickorna rhythmic gymnastics troupe, involving ribbon choreography to an instrumental version of "Fångad av en stormvind", and the previous year's winning artist Carola who sang the song "All the Reasons to Live".[28][29] The interval act, entitled "A Century of Dance", featured David Johnson, Teresa Ibrahim, the Crazy Feat dance troupe and dancers from the Nöjesteatern in a performance that showed the evolution of dance in Sweden and worldwide over the previous century; among the music pieces featured during the performance was "It Must Have Been Love" originally recorded by the Swedish duo Roxette.[26][28][30] The trophy awarded to the winners was presented at the end of the broadcast by Carola.[30]

The winner was Ireland represented by the song "Why Me?", written by Johnny Logan and performed by Linda Martin.[31] This was the fourth time that Ireland had won the contest, following victories in 1970, 1980 and 1987.[32] Having come second at the 1984 contest, Martin became the third artist to have placed both first and second in the contest, alongside Lys Assia and Gigliola Cinquetti, and songwriter Logan, who had already won the contest twice as a performer in 1980 and 1987 – the latter win additionally as the songwriter – became the third individual to record two songwriting wins, alongside Willy van Hemert and Yves Dessca, and became the first, and as of 2023[update] only, individual to record three wins as either singer or songwriter.[11][33][34] The United Kingdom finished in second place for a record-extending thirteenth time, while Malta and Greece recorded their best ever results to date with third- and fifth-place finishes respectively.[35][36][37] Conversely host country Sweden recorded one of their worst ever results, finishing 22nd and second-to-last, and Finland picked up their seventh last-place finish.[1][28] With Ireland, the United Kingdom and Malta taking the top three places, it was the first time that the top three songs had been performed in English.[6]

| R/O | Country | Artist | Song | Points | Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Serafín | "Todo esto es la música" | 37 | 14 | |

| 2 | Morgane | "Nous on veut des violons" | 11 | 20 | |

| 3 | Dafna | "Ze Rak Sport" | 85 | 6 | |

| 4 | Aylin Vatankoş | "Yaz Bitti" | 17 | 19 | |

| 5 | Cleopatra | "Olou tou kosmou i elpida" | 94 | 5 | |

| 6 | Kali | "Monte la riviè" | 73 | 8 | |

| 7 | Christer Björkman | "I morgon är en annan dag" | 9 | 22 | |

| 8 | Dina | "Amor d'água fresca" | 26 | 17 | |

| 9 | Evridiki | "Teriazoume" | 57 | 11 | |

| 10 | Mary Spiteri | "Little Child" | 123 | 3 | |

| 11 | Heart 2 Heart | "Nei eða já" | 80 | 7 | |

| 12 | Pave | "Yamma Yamma" | 4 | 23 | |

| 13 | Daisy Auvray | "Mister Music Man" | 32 | 15 | |

| 14 | Marion Welter and Kontinent | "Sou fräi" | 10 | 21 | |

| 15 | Tony Wegas | "Zusammen geh'n" | 63 | 10 | |

| 16 | Michael Ball | "One Step Out of Time" | 139 | 2 | |

| 17 | Linda Martin | "Why Me" | 155 | 1 | |

| 18 | Lotte Nilsson and Kenny Lübcke | "Alt det som ingen ser" | 47 | 12 | |

| 19 | Mia Martini | "Rapsodia" | 111 | 4 | |

| 20 | Extra Nena | "Ljubim te pesmama" | 44 | 13 | |

| 21 | Merethe Trøan | "Visjoner" | 23 | 18 | |

| 22 | Wind | "Träume sind für alle da" | 27 | 16 | |

| 23 | Humphrey Campbell | "Wijs me de weg" | 67 | 9 |

Spokespersons

Each country nominated a spokesperson, connected to the contest venue via telephone lines and responsible for announcing, in English or French, the votes for their respective country.[19][39] Known spokespersons at the 1992 contest are listed below.

France – Olivier Minne[40]

France – Olivier Minne[40] Ireland – Eileen Dunne[41]

Ireland – Eileen Dunne[41] Italy – Nicoletta Orsomando[42]

Italy – Nicoletta Orsomando[42] Malta – Joanna Drake[43]

Malta – Joanna Drake[43] Sweden – Jan Jingryd[29]

Sweden – Jan Jingryd[29] United Kingdom – Colin Berry[24]

United Kingdom – Colin Berry[24]

Detailed voting results

Jury voting was used to determine the points awarded by all countries.[24] The announcement of the results from each country was conducted in the order in which they performed, with the spokespersons announcing their country's points in English or French in ascending order.[26][24] The detailed breakdown of the points awarded by each country is listed in the tables below.

| Spain | 37 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 1 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 11 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Israel | 85 | 10 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 3 | |||||||

| Turkey | 17 | 8 | 3 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Greece | 94 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 12 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 12 | 7 | 8 | 4 | |||||||||

| France | 73 | 6 | 12 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 12 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 3 | 6 | ||||||||||||

| Sweden | 9 | 1 | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Portugal | 26 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 8 | |||||||||||||||||

| Cyprus | 57 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 8 | |||||||||||

| Malta | 123 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 12 | 12 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 12 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 3 | 10 | 5 | ||||||||

| Iceland | 80 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 12 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 2 | ||||||||

| Finland | 4 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Switzerland | 32 | 5 | 12 | 4 | 1 | 10 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Luxembourg | 10 | 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Austria | 63 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 12 | 7 | |||||||||||||

| United Kingdom | 139 | 5 | 12 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 12 | 7 | 12 | 8 | 12 | 7 | |||||

| Ireland | 155 | 1 | 7 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 12 | 7 | 10 | 6 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 10 | 10 | |||

| Denmark | 47 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 5 | |||||||||||||

| Italy | 111 | 5 | 3 | 12 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 7 | 6 | 12 | 1 | 12 | |||||||||

| Yugoslavia | 44 | 10 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Norway | 23 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Germany | 27 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Netherlands | 67 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 7 | |||||||||

12 points

The below table summarises how the maximum 12 points were awarded from one country to another. The winning country is shown in bold. Italy, Malta and the United Kingdom each received the maximum score of 12 points from four of the voting countries, with Ireland receiving three sets of 12 points, France and Greece receiving two sets of maximum scores each, and Austria, Iceland, Israel and Switzerland each receiving one maximum score.[44][45]

| N. | Contestant | Nation(s) giving 12 points |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | ||

| 3 | ||

| 2 | ||

| 1 | ||

Broadcasts

Each participating broadcaster was required to relay the contest via its networks. Non-participating broadcasters were also able to relay the contest as "passive participants". Broadcasters were able to send commentators to provide coverage of the contest in their own native language and to relay information about the artists and songs to their television viewers.[21] The contest was broadcast in 44 countries, including Australia, New Zealand and South Korea.[2][46] Known details on the broadcasts in each country, including the specific broadcasting stations and commentators are shown in the tables below.

| Country | Broadcaster | Channel(s) | Commentator(s) | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBS | SBS TV[c] | [77] | ||

| ČT | F1[d] | [78] | ||

| ETV | Ivo Linna and Olavi Pihlamägi | [79][80] | ||

| MTV | MTV1 | István Vágó | [81] | |

| TVP | TVP1 | Artur Orzech and Maria Szabłowska | [82][83] | |

| TVR | TVR 1[e] | [84] | ||

| RTR | RTR | [85] | ||

| RTVSLO | SLO 1 | [86] | ||

Notes and references

Footnotes

References

- ^ a b "Sweden – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- ^ a b "Malmö stad - Isstadion". Malmö stad. 19 March 2007. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ "Malmö stad - Isstadion". Malmö stad. 21 July 2023. Archived from the original on 11 August 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Watch Now #EurovisionAgain: Malmö 1992". European Broadcasting Union. 21 August 2021. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Malmö 1992 – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ O'Connor, John Kennedy (2010). The Eurovision Song Contest: The Official History (2nd ed.). London, United Kingdom: Carlton Books. pp. 124–127. ISBN 978-1-84732-521-1.

- ^ Escudero, Victor M. (17 September 2017). "Rock me baby! Looking back at Yugoslavia at Eurovision". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ "RTS: "Evrosong" treba da bude mesto zajedništva naroda" [RTS: "Eurosong" should be a place of unity of the people] (in Serbian). Radio Television of Serbia. 14 April 2017. Archived from the original on 15 April 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. pp. 98–108. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- ^ a b c d e O'Connor, John Kennedy (2010). The Eurovision Song Contest: The Official History (2nd ed.). London, United Kingdom: Carlton Books. pp. 128–131. ISBN 978-1-84732-521-1.

- ^ "Marion Welter & Kontinent". eurovision-spain.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ Kasapoglou, Yiorgos (26 January 2007). "Cyprus decided: Evridiki again - ESCToday.com". ESCToday. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ "Participants of Malmö 1992". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ "1992 – 37th edition". diggiloo.net. Archived from the original on 22 March 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ "Alle deutschen ESC-Acts und ihre Titel" [All German ESC acts and their songs]. www.eurovision.de (in German). ARD. Archived from the original on 12 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- ^ O'Connor, John Kennedy (2010). The Eurovision Song Contest: The Official History (2nd ed.). London, United Kingdom: Carlton Books. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-84732-521-1.

- ^ a b c "How it works – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. 18 May 2019. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Jerusalem 1999 – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

For the first time since the 1970s participants were free to choose which language they performed in.

- ^ a b c "The Rules of the Contest". European Broadcasting Union. 31 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ Escudero, Victor M. (18 April 2020). "#EurovisionAgain travels back to Dublin 1997". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

The orchestra also saw their days numbered as, from 1997, full backing tracks were allowed without restriction, meaning that the songs could be accompanied by pre-recorded music instead of the live orchestra.

- ^ "In a Nutshell – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. 31 March 2017. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. pp. 108–110. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- ^ Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- ^ a b c d e Eurovision Song Contest 1992 (Television programme). Malmö, Sweden: Sveriges Television. 9 May 1992.

- ^ Harding, Peter (May 1992). Swedish singer Carola during Eurovision dress rehearsal (1992) (Photograph). Malmö Isstadion, Malmö, Sweden. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2023 – via RTÉ Libraries and Archives.

- ^ a b c d "Revisiting Malmö: How they did it in 1992". European Broadcasting Union. 30 November 2023. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d Thorsson, Leif; Verhage, Martin (2006). Melodifestivalen genom tiderna : de svenska uttagningarna och internationella finalerna [Melodifestivalen through the ages: the Swedish selections and international finals] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Premium Publishing. pp. 228–229. ISBN 91-89136-29-2.

- ^ a b O'Connor, John Kennedy (2010). The Eurovision Song Contest: The Official History (2nd ed.). London, United Kingdom: Carlton Books. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-84732-521-1.

- ^ "Linda Martin – Ireland – Malmö". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 28 January 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ "Ireland – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Johnny Logan: What the original double winner did next". European Broadcasting Union. 14 September 2023. Archived from the original on 18 September 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ "Wouter Hardy met Zwitserland op weg naar nieuw songfestivalsucces" [Wouter Hardy on the way to new Eurovision success with Switzerland]. Ditjes en Datjes (in Dutch). 20 May 2021. Archived from the original on 25 October 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ "United Kingdom – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ "Malta – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ "Greece – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ "Final of Malmö 1992". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Lugano to Liverpool: Broadcasting Eurovision". National Science and Media Museum. 24 May 2021. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ "Introducing Hosts: Carla, Élodie Gossuin and Olivier Minne". European Broadcasting Union. 18 December 2021. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

Olivier is no stranger to the Eurovision family, too, having presented the French votes in 1992 and 1993, as well as providing broadcast commentary from 1995 through 1997.

- ^ O'Loughlin, Mikie (8 June 2021). "RTE Eileen Dunne's marriage to soap star Macdara O'Fatharta, their wedding day and grown up son Cormac". RSVP Live. Reach plc. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ Abbate, Mauro (7 May 2022). "Italia all'Eurovision Song Contest: tutti i numeri del nostro Paese nella kermesse europea" [Italy at the Eurovision Song Contest: all the numbers about our country in the European event] (in Italian). Notizie Musica. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ a b "'Great interest' in Malta's 'Little Child'". Times of Malta. 9 May 1992. p. 18.

- ^ a b c "Results of the Final of Malmö 1992". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "Eurovision Song Contest 1992 – Scoreboard". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Mattila, Ilkka (9 May 1992). "Euroviisusirkus on entistä massiivisempi" [The Eurovision circus is even more massive]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Samedi 9 mai" [Saturday 9 May]. TV8 (in French). Cheseaux-sur-Lausanne, Switzerland: Ringier. 30 April 1992. pp. 66–71. Retrieved 18 November 2022 – via Scriptorium Digital Library.

- ^ Halbhuber, Axel (22 May 2015). "Ein virtueller Disput der ESC-Kommentatoren" [A virtual dispute between Eurovision commentators]. Kurier (in German). Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ a b "TV Programma's" [TV Programmes]. De Voorpost (in Dutch). 8 May 1992. p. 15. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ Wynants, Jean-Marie (9 May 1992). "Nous, on veut des chansons! Retour à la foire annuelle à la ritournelle" [We want songs! Return to the annual show with the refrain]. Le Soir (in French). Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "Jaaroverzicht 1992" [Annual review 1992] (PDF). Belgische Radio- en Televisieomroep Nederlandstalige Uitzendingen (BRTN) (in Dutch). pp. 105–106. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Karnakis, Kostas (24 February 2019). "H Eυριδίκη επιστρέφει στην... Eurovision! Όλες οι λεπτομέρειες..." [Evridiki returns to... Eurovision! All the details...]. AlphaNews (in Greek). Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ "Programoversigt – 09/05/1992" [Program overview – 09/05/1992] (in Danish). LARM.fm. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Televisio & Radio" [Television & Radio]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). 9 May 1992. pp. D11–D12. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Radio- en TV-Programma's Zaterdag" [Radio and TV Programmes on Saturday]. Leidse Courant (in Dutch). 9 May 1992. p. 13. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Jan Hofer sagt "Tschau" zur Tagesschau" [Jan Hofer says "goodbye" to the Tagesschau]. egoFM (in German). 14 December 2020. Archived from the original on 25 November 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ "Το πρόγραμμα της τηλεόρασης" [TV schedule] (PDF). Imerisia (in Greek). 9 May 1992. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022 – via Public Central Library of Veria.

- ^ "Eurovision 2020: Γιώργος Καπουτζίδης -Μαρία Κοζάκου στον σχολιασμό του διαγωνισμού για την ΕΡΤ" [Eurovision 2020: Giorgos Kapoutzidis and Maria Kozakou to comment on the contest for ERT] (in Greek). Matrix24. 12 February 2020. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Á dagskrá – laugurdagur 9. maí" [On the agenda – Saturday 9 May]. Morgunblaðið (in Icelandic). 8 May 1992. p. 2. Retrieved 18 November 2022 – via Timarit.is.

- ^ "Weekend TV Highlights". The Irish Times Weekend. 9 May 1992. p. 7. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ "Radio". The Irish Times Weekend. 9 May 1992. p. 6. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ "שבת 9.5 – טלוויזיה" [Saturday 9.5 – Television]. Hadashot (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv, Israel. 8 May 1992. p. 102. Retrieved 22 May 2023 – via National Library of Israel.

- ^ a b "I programmi di oggi" [Today's programmes]. La Stampa (in Italian). 9 May 1992. p. 19. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ Lombardini, Emanuele (28 March 2014). "Peppi Franzelin ci racconta gli ESC 1990 e 1992. E la Cinquetti..." [Peppi Franzelin tells us about ESC 1990 and 1992. And Cinquetti...] (in Italian). Eurofestival News. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Radio Television". Times of Malta. 9 May 1992. p. 18.

- ^ a b c "Radio og TV – lørdag 9. mai" [Radio and TV – Saturday 9 May]. Oppland Arbeiderblad (in Norwegian). 9 May 1992. pp. 60–61. Retrieved 18 November 2022 – via National Library of Norway.

- ^ "P2 – Kjøreplan lørdag 9. mai 1992" [P2 – Schedule Saturday 9 May 1992] (in Norwegian). NRK. 9 May 1992. p. 9. Retrieved 18 November 2022 – via National Library of Norway. (subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries)

- ^ "Programa da televisão" [Television schedule]. A Comarca de Arganil (in Portuguese). 7 May 1992. p. 8. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ Firmino, Tiago (7 April 2018). "O número do dia. Quantos festivais comentou Eládio Clímaco na televisão portuguesa?" [The number of the day. How many festivals did Eládio Clímaco comment on on Portuguese television?] (in Portuguese). N-TV. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Televisión" [Television]. La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 9 May 1992. p. 6. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Albert, Antonio (9 May 1992). "Festival de Eurovisión" [Eurovision Festival]. El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ a b "TV + Radio Samedi" [TV + Radio Saturday]. Journal de Jura (in French). 9 May 1992. p. 21. Retrieved 18 November 2022 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "Samedi 9 mai" [Saturday 9 May]. Le Matin (in French). Lausanne, Switzerland: Edipresse. 9 May 1992. p. 28. Retrieved 18 November 2022 – via Scriptorium Digital Library.

- ^ "Televizyon" [Television]. Cumhuriyet (in Turkish). 9 May 1992. p. 10. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ "Eurovision Song Contest – BBC One". Radio Times. 9 May 1992. Retrieved 18 November 2022 – via BBC Genome Project.

- ^ "Eurovision Song Contest – BBC Radio 2". Radio Times. 9 May 1992. Retrieved 18 November 2022 – via BBC Genome Project.

- ^ a b c "Today's television". The Canberra Times. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 10 May 1992. p. 28. Retrieved 18 November 2022 – via Trove.

- ^ "Televízió – Kűlfőldi tévéműsorok – péntek május 15" [Television - Foreign TV programs - Friday, May 15]. Rádió és TeleVízió újság (in Hungarian). 11 May 1992. p. 47. Archived from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2022 – via MTVA Archívum.

- ^ "Televisiooni nädalakava 4. mai–10. mai" [Television weekly schedule 4 May–10 May]. Päevaleht (in Estonian). 1 May 1992. p. 14. Retrieved 28 October 2022 – via DIGAR Eesti artiklid.

- ^ "ETV 1992 | ajalugu". Eesti Rahvusringhääling. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ "Televízió – szombat május 9" [Television – Saturday 15 May]. Rádió és TeleVízió újság (in Hungarian). 4 May 1992. p. 50. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022 – via MTVA Archívum.

- ^ "Telewizja Polska – sobota, 9 maja" [Polish Television – Saturday, 9 May] (PDF). Kurier Wileński (in Polish). 2 May 1992. p. 8. Retrieved 28 October 2022 – via Polonijna Biblioteka Cyfrowa.

- ^ "Marek Sierocki i Aleksander Sikora skomentują Eurowizję! Co za duet!" [Marek Sierocki and Aleksander Sikora will comment on Eurovision! What a duo!]. pomponik.pl (in Polish). 30 April 2021. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Televiziune – sâmbătă 9 mai 1992" [Television – Saturday 9 May 1992]. Panoramic Radio-TV (in Romanian). p. 6.

- ^ "Телевидение" [Television] (PDF). Pravda (in Russian). 9 May 1992. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Sobota, 9. maja 1992" [Saturday, 9 May 1992] (PDF). Gorenjski glas (in Slovenian). 8 May 1992. p. 15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2022.