Ezra Stiles

Ezra Stiles | |

|---|---|

Stiles, 1770–1771, by Samuel King | |

| 7th President of Yale University | |

| In office 1778–1795 | |

| Preceded by | Naphtali Daggett as pro tempore |

| Succeeded by | Timothy Dwight IV |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 December [O.S. 29 November] 1727 North Haven, Connecticut Colony |

| Died | May 12, 1795 (aged 67) New Haven, Connecticut |

| Relations | Edward Taylor (grandfather) |

| Children | Betsey Stiles; Ruth (Stiles) Gannett; Emilia (Stiles) Leavitt; Polly (Stiles) Holmes; Isaac Stiles |

| Residence | Ezra Stiles House (1756–1776) |

| Education | Yale College |

| Signature | |

Ezra Stiles (10 December [O.S. 29 November] 1727 – May 12, 1795)[1][2] was an American educator, academic, Congregationalist minister, theologian, and author. He is noted as the seventh president of Yale College (1778–1795) and one of the founders of Brown University.[3][4] According to religious historian Timothy L. Hall, Stiles' tenure at Yale distinguishes him as "one of the first great American college presidents."[5]

Early life

Ezra Stiles was born on 10 December [O.S. 29 November] 1727 in North Haven, Connecticut, to Rev. Isaac Stiles and Kezia Taylor Stiles (1702–1727). His maternal grandfather, Edward Taylor had emigrated to Colonial America from Leicestershire, England, in 1668.[6] Kezia Taylor Stiles died four days after giving birth to Ezra.[5][7]

Stiles received his early education at home and matriculated at Yale College in September 1742, as one of 13 members of the college's freshman class. At Yale, he studied a liberal arts curriculum characterized by an uncertain period of transition between moribund Puritan thought and that of newer thinkers like John Locke and Isaac Newton. Stiles also studied works by Thomas Farnaby, Isaac Watts, and John Ward. According to biographer Edmund Morgan, the young Stiles read "a strange conglomeration of the first-rate and the third-rate" authors.[7] He graduated in 1746.[8] Stiles was conferred a perfunctory Master of Arts degree from Yale and became ordained in 1749 after further studies in theology.[7]

From 1749 to 1755, Stiles worked as a tutor at Yale. During this period, he drifted away from Calvinism and preached to Native Americans in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.[5][9] In a 1762 letter, Samuel Johnson notes that the young Stiles at one point nearly became an Anglican, writing that he "was once on the point of conforming to the Church, but was dissuaded by his friends, and is become much of a Latitudinarian."[10]

In 1753 Stiles resigned from his position as a tutor to pursue a career in law and practice at New Haven. Stiles qualified for the New Haven bar by November 13, 1753, after reading law.[7] After two years, he returned to his service as a Congregationalist minister.

In 1768, Stiles was elected to the American Philosophical Society.[11] In 1784, he was elected an honorary member of the Society of the Cincinnati of Connecticut, one of the first so honored, for his ardent support of the Patriot cause.

Newport (1755-1776)

In 1752, Stiles traveled to Newport, Rhode Island, for his health. During his trip, the city's Trinity Church—the largest Anglican congregation in New England—sought Stiles to serve as its minister, offering him a salary of £200 sterling.[12] Stiles rejected the offer and departed from the city, writing "that all his Art and Address and fine offers were ineffectual."[7]

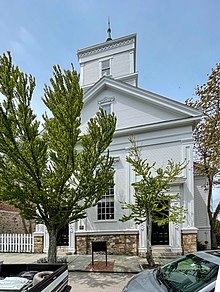

In 1755, the Second Congregational Church of Newport likewise sought out the young minister. In August, after serving in an interim capacity, he joined the church as for a salary of £65 Sterling. In the later months 1756, a clapboard house was constructed for Stiles on Clark Street, across from the meeting house of his congregation.[7] Since 1972, the residence has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In September of the same year, Stiles was made Librarian of the Redwood Library and Athenaeum, a position that allowed him access to books at his discretion.[13] During his years in Newport, Stiles kept an informative diary of his life and acquaintances, which detailed—among other things—his association with Portuguese merchant Aaron Lopez.

In 1757, Stiles married Elizabeth Hubbard, with whom he had eight children.[5]

Slavery

From time to time, Stiles invested with the merchants and sea captains of his congregation; in 1756, he sent a hogshead of rum along on a voyage to Africa and was repaid with a 10-year-old male slave, whom he renamed "Newport". Around the same time, he wrote a joint letter with fellow Newport minister Samuel Hopkins condemning "the great inhumanity and cruelty" of slavery in the United States.[14]

Foundation of Brown University

During his residence in Newport, Stiles played a major role in the establishment of Brown University (then Rhode Island College).

According to Edmund Morgan, in Rhode Island's religious diversity Stiles "saw an opportunity to join with Christians of other denominations in a project which would exemplify their common faith in free inquiry.... a college in which the major religious groups of the colony should unite in the pursuit of knowledge."[7] In 1761, Stiles, along with William Ellery Jr. and Josias Lyndon, drafted a petition to the Rhode Island General Assembly to establish a "literary institution".[15] The editor of Stiles's papers observes, "This draft of a petition connects itself with other evidence of Dr. Stiles's project for a Collegiate Institution in Rhode Island, before the charter of what became Brown University."[15][16]

There is further documentary evidence that Stiles was making plans for a college in 1762. On January 20, Chauncey Whittelsey, pastor of the First Church of New Haven, answered a letter from Stiles:[17]

The week before last I sent you the Copy of Yale College Charter ... Should you make any Progress in the Affair of a Colledge, I should be glad to hear of it; I heartily wish you Success therein.

Stiles agreed to write the Charter for the college, submitting a first draft to the General Assembly in August 1763. A revised version of the Charter written by Stiles and Ellery was adopted by the Rhode Island General Assembly on March 3, 1764, in East Greenwich.[18] In drafting the document, Stiles combined broad-minded public statements defining Rhode Island College as a "liberal and catholic institution" in which "shall never be admitted a religious test" with private partisanship: his draft charter packed the board of trustees and the fellows of the college with his fellow Congregationalists.

Baptist members of the Rhode Island General Assembly, to Stiles' dismay, amended the charter to allow Baptists control of both branches of the College's Corporation.[19] Stiles declined a seat on the College's Corporation, writing that Baptists had seized "the whole Power and Government of the College and thus by the Immutability of the numbers establishing it a Party College." Stiles continued to work towards his vision of a non-sectarian institution after the establishment of Rhode Island College, presenting in 1770 a petition for the establishment of another college in Newport.[7]

Scholarship

Semitic scholarship

Stiles struck up a close friendship with Haim Isaac Carigal of Hebron during the Rabbi's 1773 residence in Newport.[20] Stiles' records note 28 meetings to discuss a wide variety of topics from Kabbalah to the politics of the Holy Land.[21] Stiles improved his rudimentary knowledge of Hebrew, to the point where he and Carigal corresponded by mail in the language.[22] Stiles' knowledge of Hebrew also enabled him to translate large portions of the Hebrew Old Testament into English. Stiles believed, as did many Christian scholars of the time, that facility with the text in its original language was advantageous for proper interpretation.

Native American scholarship

Stiles conducted research on the Native Americans of New England. In 1761, he visited a Native American village in Niantic, Connecticut, where he recorded notes on the traditional construction methods of wigwams. Stiles additionally documented information on the languages and petroglyphs of New England's native peoples. According to archaeologist Edward J. Lenik, Stiles "produced one of the most important early records of petroglyphs and American Indian life in New England."[9]

American Revolution

Stiles left Newport in 1776 prior to the arrival of British troops and their subsequent occupation of the city. In 1776 and 1777, Stiles served briefly as minister of the Dighton Community Church in Dighton, Massachusetts.[5]

In 1777, Stiles became pastor of North Church in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. As pastor, he defended the monarchy as the best form of government in his sermon, entitled The United States elevated to Glory and Honor, to the General Assembly of the State of Connecticut in 1783. He stated that "a monarchy conducted with infinite wisdom and infinite benevolence is the most perfect of all possible governments."

Yale presidency

In 1778, Stiles was appointed president of Yale, a post he held until his death. He freed his slave Newport on June 9, 1778, as he prepared to move to New Haven; he would in 1782 hire his former slave for $20 a year and indentured Newport's two-year-old son until age 24.[23] As president of Yale, Stiles became its first professor of Semitics, and required all students to study Hebrew (as Harvard students already did); his first commencement address in September 1781 (no ceremonies having been held during the American Revolutionary War) was delivered in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic. By 1790, however, he was forced to face failure in instilling an interest in the language in the student body, writing

From my first accession to the Presidency ... I have obliged all the Freshmen to study Hebrew. This has proved very disagreeable to a Number of the Students. This year I have determined to instruct only those who offer themselves voluntarily.

The valedictorians of 1785 and 1792, however, did deliver their speeches in Hebrew.[24]

Stiles was an amateur scientist who corresponded with Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin about scientific discoveries. Using equipment donated to the college by Franklin, Stiles conducted the electrical experiments in New England, continuing a practice first begun by his predecessor, President Thomas Clap. He charged a glass tube with static electricity and used it to "excite the wonder and admiration of an audience".[25] He shocked 52 people at once, fired spirits of wine and rum, and caused counterfeit spiders to move about as if they were alive. These were all experiments that had been performed before, and "Stiles seems to have had little genius for pushing back the frontiers of knowledge" and his observations "disclosed nothing new".[25] He was more a learner and teacher than an experimenter. Nevertheless, he was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1781.[26]

His book The United States elevated to Glory and Honor was printed in 1783.[27] The book is a transcript of a sermon given to the Connecticut General Assembly, on May 8, 1783. The sermon draws parallels between the United States and the Biblical nation of Israel. Stiles refers to the US as an "American Israel, high above all nations which He hath made, in numbers, and in praise, and in name, and in honor", suggesting that the White Americans are like the Chosen People of Israel. He opined that "in God’s good providence" Indians and Africans "may gradually vanish", thus ensuring that "an unrighteous SLAVERY may at length, in God’s good providence, be abolished and cease in the land of LIBERTY."[28]

Death and legacy at Yale

Stiles died in New Haven in 1795, while serving as president.

It is false that Stiles is responsible for the addition of the Hebrew words "Urim" and "Thummim" (Hebrew: אורים ותמים) to the Yale seal. Indeed, the Hebrew on the Yale seal appears on Stiles' own master's degree diploma from Yale in 1749, decades before he became president of Yale College.[29]

In 1961, Yale named a new residential college in his honor: Ezra Stiles College. The college is noted for its design by modernist architect Eero Saarinen.

Stiles' upholstered armchair is currently in the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut. The chair was made in Newport, Rhode Island.[30]

Family

Stiles married twice (Elizabeth Hubbard and Mary Checkley Cranston) and had eight children. Stiles' son Ezra Stiles, Esq., was educated first at Yale College, then at Harvard College, where he studied law, graduating in 1778. Ezra Stiles Jr., subsequently settled in Vermont, and served to establish the boundaries between Vermont and New Hampshire. He died prematurely at Chowan County, North Carolina, on August 22, 1784, and his two daughters by his wife Sylvia (Avery) Stiles of Vermont (and formerly of Norwich, Connecticut) had their uncle Jonathan Leavitt appointed their guardian.[31]

Stiles' daughter Emilia married Judge and State Senator Jonathan Leavitt of Greenfield, Massachusetts. His daughter Mary married, in 1790, Abiel Holmes, a Congregational clergyman and historian and a 1783 graduate of Yale College. By his second marriage to Sarah Wendell, Abiel was the father of Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

References

- ^ Stiles, Ezra (1901). The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles: Jan. 1, 1769l-Mar. 13, 1776. C. Scribner's sons. p. 1.

- ^ Holmes, Abiel (1798). The Life of Ezra Stiles ... President of Yale College, p. 9.

- ^ Welch, Lewis et al. (1899). Yale, Her Campus, Class-rooms, and Athletics, p. 445.

- ^ Edmund S Morgan, The Gentle Puritan: A Life of Ezra Stiles, 1727–1795 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1962), 205.

- ^ a b c d e Hall, Timothy L. (2003). American Religious Leaders. New York: Facts On File. p. 343. ISBN 0-8160-4534-8. OCLC 49284351.

- ^ "Edward Taylor". Poetry Foundation. May 1, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Morgan, Edmund S. (January 1, 2014). The Gentle Puritan: A Life of Ezra Stiles, 1727-1795. UNC Press Books. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-8078-3972-0.

- ^ Morgan, Edmund S. (1954). "Ezra Stiles: The Education of a Yale Man, 1742-1746". Huntington Library Quarterly. 17 (3): 251–268. doi:10.2307/3816428. ISSN 0018-7895. JSTOR 3816428.

- ^ a b Lenik, Edward J. (2009). Making Pictures in Stone: American Indian Rock Art of the Northeast. University of Alabama Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8173-5509-8.

- ^ Johnson, Samuel, Samuel Johnson, President of King's College; His Career and Writings, edited by Herbert and Carol Schneider, New York: Columbia University Press, 1929, Volume 1, p. 321

- ^ Bell, Whitfield J., and Charles Greifenstein Jr. Patriot-Improvers: Biographical Sketches of Members of the American Philosophical Society. 3 vols. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1997, I:119, 149, 152, 155, 156, 477, 487, 505, II:13, 209, 217, 219, 276, III:16, 52, 189, 296–392, 297, 431, 481, 604, 607, 608, 613.

- ^ R.I.), Trinity Church (Newport; Mason, George Champlin (1890). Annals of Trinity Church, Newport, Rhode Island. 1698-1821. G.C. Mason. p. 103.

- ^ Annual Report of the Redwood Library and Athenaeum. Newport, RI: Davis & Pitman, Book and Job Printers. September 28, 1881. p. 11.

- ^ Dugdale, Antony; J. J. Fueser; J. Celso de Castro Alves (2001). "Ezra Stiles College". Yale, Slavery, & Abolition. The Amistad Committee. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ a b Stiles, Ezra (1916). Dexter, Franklin Bowditch (ed.). Extracts From the Itineraries and Other Miscellanies of Ezra Stiles, D. D., Ll. D., 1755-1794: With a Selection From His Correspondence. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 25.

- ^ Dexter (1916), p. 25.

- ^ Bronson, Walter Cochrane (1914). The History of Brown University, 1764-1914. Internet Archive. Providence, The University. pp. 346–347. ISBN 978-0-405-03697-2.

- ^ "Encyclopedia Brunoniana | Charter". www.brown.edu. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ Hoeveler, David J., Creating the American Mind: Intellect and Politics in the Colonial Colleges, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, p. 191

- ^ "The Rabbi from Hebron and the President of Yale". the Jewish Community of Hebron. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Geffen, Rabbi David (May 13, 2021). "Hebron Rabbi Spoke on Shavuot in 1773 Newport". Atlanta Jewish Times. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Stiles, Ezra; Kohut, George Alexander (1902). Ezra Stiles and the Jews; selected passages from his Literary diary concerning Jews and Judaism. University of California Libraries. New York, P. Cowen.

- ^ Saillant, John, Black Puritan, Black Republican: The Life and Thought of Lemuel Haynes, 1753–1833, Oxford University Press, 2002, p. 131

- ^ "How Hebrew Came to Yale | Yale University Library". web.library.yale.edu. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ a b Morgan, Edmund, The Gentle Puritan: A Life of Ezra Stiles, 1727–1795, University of North Carolina Press, 2014, p. 91

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter S" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ Stiles, Ezra; Smolinski, Reiner (January 1783). "The United States Elevated to Glory and Honor". Electronic Texts in American Studies.

- ^ Guyatt, Nicholas (2007). Providence and the Invention of the United States, 1607-1876. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86788-7.

- ^ Oren, Dan A. (2001) Joining the Club: A History of Jews and Yale, Revised edition, p. 347.

- ^ "Upholdtered armchair, RIF5502". The Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- ^ The Stiles Family in America, Genealogies of the Connecticut Family, Henry Reed Stiles, Doan & Pilson, Jersey City, 1895

Further reading

- Dexter, Franklin Bowditch. (1901). The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles (Vol. I, January 1, 1769 – March 13, 1776). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- __________. (1901). The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles Vol. II, March 14, 1776 – December 31, 1781. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. OCLC 2198912

- __________. (1901). The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles (Vol. III, January 1, 1782 – May 6, 1795). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Grasso, Christopher (1999). A Speaking Aristocracy: Transforming Public Discourse in Eighteenth-Century Connecticut. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4772-5.

- Holmes, Abiel. (1798). The Life of Ezra Stiles D.D. LL.D. ... President of Yale College. Boston: Thomas & Andrews. OCLC 11506585

- Kelley, Brooks Mather. (1999). Yale: A History. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07843-5; OCLC 810552

- Morgan, Edmund Sears. (1983). The Gentle Puritan: A Life of Ezra Stiles, 1727–1795. The gentle puritan: a life of Ezra Stiles, 1727–1795. Raleigh: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1231-0

- Welch, Lewis Sheldon and Walter Camp. (1899). Yale, Her Campus, Class-rooms, and Athletics. Boston: L. C. Page and Co. OCLC 2191518

External links

- Brown University's John Hay Library

- Brown University Charter

- Ezra Stiles Papers. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.