First wave feminism

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

|

|

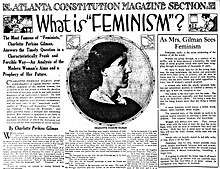

First-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity and thought that occurred during the 19th and early 20th century throughout the Western world. It focused on legal issues, primarily on securing women's right to vote. The term is often used synonymously with the kind of feminism espoused by the liberal women's rights movement with roots in the first wave, with organizations such as the International Alliance of Women and its affiliates. This feminist movement still focuses on equality from a mainly legal perspective.[1]

The term first-wave feminism itself was coined by journalist Martha Lear in a New York Times Magazine article in March 1968, "The Second Feminist Wave: What do these women want?"[2][3][4] First- wave feminism is characterized as focusing on the fight for women's political power, as opposed to de facto unofficial inequalities. The first wave of feminism generally advocated for formal equality, while later waves typically advocated for substantive equality.[5] The wave metaphor is well established, including in academic literature, but has been criticized for creating a narrow view of women's liberation that erases the lineage of activism and focuses on specific visible actors.[6] The term "first-wave" and, more broadly, the wave model have been questioned when referencing women's movements in non Western contexts because the periodization and the development of the terminology were entirely based on the happenings of western feminism and thus cannot be applied to non western events in an exact manner. However, women participating in political activism for gender equity modeled their plans on western feminists demands for legal rights. This is connected to the western first-wave and occurred in the late 19th century and continued into the 1930s in connection to the anti-colonial nationalist movement.

Global terminologies

The issues of inclusion that began during the first-wave of the feminist movement in the United States and persisted throughout subsequent waves of feminism are the topic of much discussion on an academic level. Some scholars find the wave model of western feminism to be troubling because it condenses a long history of activism into distinct categories that characterize generations of activists instead of acknowledging a complex, interconnected, and intersectional history of women's rights. This is thought to diminish the struggles and achievements of many people as well as worsen the separations between marginalized feminists.[7] The points of contention that persist in modern discussions of Western and global feminism began with the inequity that hallmarked first-wave feminism. The way in which the west has been oriented as an authority in global feminist discussions has been criticized by feminists in the United States such as bell hooks for replicating colonial hierarchies of discussion, possession of knowledge and centering gender as the foundation of equality.[8] The idea of decolonizing feminism is a response to the political and intellectual position of power western feminism holds. By acknowledging that there are multiple feminisms around the world the narrow scope and lack of consideration for intersectional identities that has persisted since first-wave feminism in the west is responded to. The existence of multiple feminisms and forms of activism is a result of the first-wave of feminism being shaped by a history of colonialism and imperialism.[9]

Origins

Movements to broaden women's rights began much earlier than the 20th century. In her book The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir wrote that the first woman to "take up her pen in defense of her sex" was Christine de Pizan in the 15th century.[10] Other "proto-feminists" working in the 15th-17th centuries include Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, Modesta di Pozzo di Forzi, Anne Bradstreet and François Poullain de la Barre.[10] Ancient literature and mythology such as Euripides' Medea have become closely associated with the feminist movement and have been interpreted as icons of feminism. Ancient literature plays an important role in feminist theory and scholarly study.[11] Olympe de Gouges is regarded as one of the first feminists. She published a pamphlet named Déclaration des Droits de la Femme et de la Citoyenne ("Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the [Female] Citizen") as a response to Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen ("Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the [Male] Citizen") in 1791.[12]

Wollstonecraft

The period in which Mary Wollstonecraft wrote was affected by Rousseau and the philosophy of the Enlightenment. The father of the Enlightenment defined an ideal democratic society that was based on the equality of men, where women were often discriminated against. The inherent exclusion of women from discussion was addressed by both Wollstonecraft and her contemporaries. Wollstonecraft based her work on the ideas of Rousseau.[13] Although at first it seems to be contradictory, Wollstonecraft's idea was to expand Rousseau's democratic society but based on gender equality. Mary Wollstonecraft spoke boldly on the inclusion of women in the public lifestyle; more specifically, narrowing down on the importance of female education.[14] She took the term 'liberal feminism' and devoted her time to breaking through the traditional gender roles.[14]

Wollstonecraft published one of the first feminist treatises, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), in which she advocated the social and moral equality of the sexes, extending the work of her 1790 pamphlet, A Vindication of the Rights of Men. Her later unfinished novel, Maria, or the Wrongs of Woman, earned her considerable criticism as she discussed women's sexual desires. She died young, and her widower, the philosopher William Godwin, quickly wrote a memoir of her that, contrary to his intentions, destroyed her reputation for generations.

Wollstonecraft is regarded as the "fore-mother" of the British feminist movement and her ideas shaped the thinking of the suffragettes, who campaigned for the women's vote.[15]

Education

Education amongst young Swiss women was very important during the suffrage movements. Educating young women in society on the importance of self-identity, and going to school was very important to the public and for women to realize what their full potential was. The Swiss suffrage movements believed it was important for young women to know that there was more to their life than just bearing children, which was a very universal thought and action during the suffrage movements in the 1960s and 70s. In a 2015 evaluation from Lord David Willetts, he had discovered and stated that in 2013 the percentage of undergraduate students in the UK were 54 percent females and 46 percent were male undergrads. Whereas in the 1960s only 25 percent of full-time students in the United Kingdom were females. The increase of females going to school and contributing in the educational system can be linked to the women's suffrage movements that aimed to encourage women to enroll in school for higher education.[16] This right and political affair eventually came after the right for women to vote in political elections which was granted in 1971. In the 1960s in the United Kingdom, women were usually the minority and a rarity when it came to the higher education system.

Country

Argentina

During the last decade of the nineteenth century and the first of the twentieth century, women in Argentina organized and consolidated one of the most complex feminist movements of the western world. Closely associated with the labor movement, they were socialists, anarchists, libertarians, emancipatorians, educationists and Catholics. In May 1910 they organized together the First International Feminist Congress. Well known European, Latin, and North American workers, intellectuals, thinkers and professionals like Marie Curie, Emilia Pardo Bazán, Ellen Key, Maria Montessori and many others presented and discussed their ideas research work and studies on themes of gender, political and civil right, divorce, economy, education, health and culture.

Australia

In 1882, Rose Scott, a women's rights activist, began to hold weekly salon meetings in her Sydney home left to her by her late mother. Through these meetings, she became well known amongst politicians, judges, philanthropists, writers and poets. In 1889, she helped to found the Women's Literary Society, which later grew into the Womanhood Suffrage League in 1891. Leading politicians hosted by Scott included Bernhard Wise, William Holman, William Morris Hughes and Thomas Bavin, who met and discussed the drafting of the bill that eventually became the Early Closing Act of 1899.[17]

Canada

Canada's first-wave of feminism became apparent in the late 19th century into the early 20th. The build up of women's movements started as consciously raising awareness, then turned into study groups, and resulted into taking action by forming committees. The premise of the movement began around education issues. The particular reason education is targeted as a high priority is because it can target younger generations and modify their gender-based opinions.[18] In 1865 the superintendent of an Ontario public school, Egerton Ryerson, was one of the first to point out the exclusion of females from the education system. As more females attended school throughout the years, they surpassed the male graduation rate. In 1880 British Columbia, 51% high school graduates were female. These percentages continued to increase right through to 1950.[18] Other reasons for the first feminist movement involved women's suffrage, and labour and health rights; thus, feminists narrowed their campaigns to focus on gaining legal and political equity.[19] Canada took action in the International Council of Women and has a specific section called the National Council of Women in Canada, with its president, Lady Aberdeen. Women started to look outside of groups such as garden and music clubs, and dive into reforms furthering better education and suffrage. It was behind the idea that the women would be more powerful if they joined to create a united voice.[20]

China

In the 1880s and 1890s, both male and female Chinese reformist intellectuals, concerned with the development of China to a modern country, raised feminist issues and gender equality in public debate; schools for girls were founded, a feminist press emerged, and the Foot Emancipation Society and Tian Zu Hui, promoting the abolition of foot binding.[21]

Many changes in women's lives took place during the Republic of China (1912–1949). In 1912, the Women's Suffrage Alliance, an umbrella organization of many local women's organizations, was founded to work for the inclusion of women's equal rights and suffrage in the constitution of the new republic after the abolition of the monarchy, and while the effort was not successful, it signified an important period of feminism activism.[22] A generation of educated and professional new women emerged after the inclusion of girls in the state school system and after women students were accted at the University of Beijing in 1920, and in the 1931 Civil Code, women were given equal inheritance rights, banned forced marriage and gave women the right to control their own money and initiate divorce.[23] No nationally unified women's movement could organize until China was unified under the Kuomintang Government in Nanjing in 1928; women's suffrage was finally included in the new Constitution of 1936, although the constitution was not implemented until 1947.[24]

Denmark

The first women's movement was led by the Dansk Kvindesamfund ("Danish Women's Society"), founded in 1871. Line Luplau was one of the most notable woman in this era. Tagea Brandt was also part of this movement, and in her honor was established the Tagea Brandt Rejselegat or Travel Scholarship for women. The Dansk Kvindesamfund's efforts as a leading group of women for women led to the existence of the revised Danish constitution of 1915, giving women the right to vote and the provision of equal opportunity laws during the 1920s, which influenced the present-day legislative measures to grant women access to education, work, marital rights and other obligations.[25]

Finland

In the mid 19th-century, Minna Canth first started to address feminist issues in public debate, such as women's education and sexual double standards.[26] The Finnish women's movement organized with the foundation of the Suomen Naisyhdistys in 1884, which was the first feminist women's organisation in Finland.[27] This represented the first wave feminism. The Suomen Naisyhdistys was split into the Naisasialiitto Unioni (1892) and the Suomalainen naisliitto (1907), and all women's organisations were united under the umbrella organisation Naisjärjestöjen Keskusliitto in 1911.

Women where granted their basic equal rights early on with the suffrage in 1906. After the introduction of women's suffrage, the women's movement was mainly channelled through the women's branches of the political parties.[28] The new marriage law of 1929, Avioliittolaki, finally established complete equality for married women, and after this, women were legally equal to men by law in Finland.[28]

France

The issue of women's rights were discussed during the Age of Enlightenment and the French Revolution. Some success was achieved by the new inheritance rights (Loi sur l'héritage des enfants) and the divorce law (Loi autorisant le divorce en France).[29]

A movement that brought feminism into play happened during the same time a republican form of government came to replace the classic Catholic monarchy. A few females took on leadership roles to form groups divided by financial stability, religion, and social status. One of these groups, the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women, managed to draw significant interest within the national political scene, and advocated for gender equality in revolutionary politics. Another such group were Société fraternelle des patriotes de l'un et l'autre sexe. These groups were driven to increase economic opportunities by hosting meetings, writing journals, and forming organizations with the same means.[30]

However, the Code Napoléon of 1804 eradicated the progress made during the revolution. Women's rights were supported by the rule of the Communist Paris Commune of 1870, but the rule of the Commune came to be temporary.

An 1897 newspaper, La Fronde, was the most prestigious women-run newspaper. It maintained as a daily paper for 6 years and covered controversial topics such as the working women and advocating for women's political rights.[31]

The First wave women's movement in France organized when the Association pour le Droit des Femmes was founded by Maria Deraismes and Léon Richer in 1870.[32] It was followed by the Ligue Française pour le Droit des Femmes (1882) which took up the issue of women suffrage and became the leading suffrage society in parallel to the Union française pour le suffrage des femmes (1909-1945).

Germany

The First wave women's movement in Germany organized under the influence of the Revolutions of 1848. It organized for the first time in the first women's organization in Germany, the Allgemeiner Deutscher Frauenverein (ADF), which was founded by Louise Otto-Peters and Auguste Schmidt in Leipzig 1865.

Women in the middle class sought improvements in their social status and prospects in society. A humanist aspiration connected the women together as they wanted to identify and be respected as full individuals.[33] They were drawn into the socialist political struggles of the revolution because they were promised full equity afterwards. The agenda of women's improvements consisted of gaining rights to work, education, abortion, contraception, and the right to seek a profession.[34] The premise of German feminism was revolved around the political common good, including social justice and family values.[35] The pressure women put on society led to women's suffrage in 1918. This created further feminist movements to expand women's rights.[35]

In comparison to the United States, German feminism targets a collective representation and women's autonomy whereas the American feminism is focused on general equality.[35]

The Netherlands

Although in the Netherlands during the Age of Enlightenment the idea of the equality of women and men made progress, no practical institutional measures or legislation resulted. In the second half of the nineteenth century, many initiatives by feminists sprung up in The Netherlands.

Aletta Jacobs (1854–1929) requested and obtained as the first woman in the Netherlands the right to study at university in 1871, becoming the first female medical doctor and academic. She became a lifelong campaigner for women's suffrage, equal rights, birth control, and international peace, travelling worldwide for, e.g., the International Alliance of Women.

Wilhelmina Drucker (1847–1925) was a politician, a prolific writer and a peace activist, who fought for the vote and equal rights through political and feminist organisations she founded. In 1917–1919, her goal of women's suffrage was reached.

Cornelia Ramondt-Hirschmann (1871–1951), President of the Dutch Women's International League for Peace and Freedom [WILPF].

Selma Meyer (1890–1941), Secretary of the Dutch Women's International League for Peace and Freedom [WILPF]

New Zealand

Early New Zealand feminists and suffragettes included Maud Pember Reeves (Australian-born; later lived in London), Kate Sheppard and Mary Ann Müller. In 1893, Elizabeth Yates became Mayor of Onehunga, the first time such a post had been held by a female anywhere in the British Empire. Early university graduates were Emily Siedeberg (doctor, graduated 1895) and Ethel Benjamin (lawyer, graduated 1897). The Female Law Practitioners Act was passed in 1896 and Benjamin was admitted as a barrister and solicitor of the Supreme Court of New Zealand in 1897 (see Women's suffrage in New Zealand).

Norway

The First wave women's movement in Norway organized when the Norwegian Association for Women's Rights was founded in 1884.

Russia

In Imperial Russia, it was not legal to form political organisations prior to the 1905 Russian Revolution. Because of this, there was no open organised women's rights movement similar to the one in the West before this. There was, however, in practice a women's movement during the 19th century.

In the mid-19th century, several literary discussion clubs were founded, one of whom, which was co-founded by Anna Filosofova, Maria Trubnikova and Nadezjda Stasova, which discussed Western feminist literature and came to be the first de facto women's rights organisation in Russia. The Crimean War had exposed Russia as less developed than Western Europe, resulting in a number of reforms, among them educational reforms and the foundation of schools for girls. Russian elite women de facto spoke for reforms in women rights through their literary clubs and charity societies. Their main interest were women's education- and work opportunities. The women's club of Anna Filosofova, Maria Trubnikova and Nadezjda Stasova managed to achieve women's access to attend courses at the universities, and the separate courses held for women became so popular that they were made permanent in 1876. However, in 1876 women students were banned from being given degrees and all women's universities were banned except two (Bestuzhev Courses in Saint Petserburg and Guerrier Courses in Moscow).[36]

In 1895, Anna Filosofova founded the "Russian Women's Charity League", which was officially a charitable society to avoid the ban of political organisations but which was in effect a women's rights organisation: Anna Filosofova was elected to the International Council of Women in 1899. Because of the ban of political activity in Russia the only thing they could do was to raise awareness of feminist issues.

After the 1905 Russian Revolution, political organisations was made legal in Russia and the women's movement was able to organise in the form of Liga ravnopraviia zhenshchin, which started a campaign of women's suffrage the same year. The Russian Revolution of 1917 formally made men and women equal in the eyes of the law in the Soviet Union.

South Korea

The Korean women's movement started in the 1890s with the foundation of Chanyang-hoe, followed by a number of other groups, primarily focused on women's education and the abolition of gender segregation and other didscriminatory practices.[37]

When Korea became a Japanese colony in 1910 women's associations were banned by the Japanese and many women instead engaged in the underground resistance groups such as the Yosong Aeguk Tongji-hoe (Patriotic Women's Society) and the Taehan Aeguk Buin-hoe (Korean Patriotic Women's Society).[37] As a result, the role of women in society began to change.[citation needed]

After the end of the War and the partition of Korea in 1945, the Korean women's movement was split. In North Korea, all women's movement was channelled in to the Korean Democratic Women's Union; in South Korea, the women's movement where united under the Korean National Council of Women in 1959, which in 1973 organized the women's group in the Pan-Women's Society for the Revision of the Family Law to revise the discriminating Family Law of 1957, a cause that remained a main focus for the rest of the 20th-century and did not result in any major reform until 1991.[37]

Sweden

Feminist issues and gender roles were discussed in media and literature during the 18th century by people such as Margareta Momma, Catharina Ahlgren, Anna Maria Rückerschöld and Hedvig Charlotta Nordenflycht, but it created no movement of any kind. The first person to hold public speeches and agitate in favor of feminism was Sophie Sager in 1848,[38] and the first organization created to deal with a women's issue was Svenska lärarinnors pensionsförening (Society for Retired Female Teachers) by Josefina Deland in 1855.[39]

In 1856, Fredrika Bremer published her famous Hertha, which aroused great controversy and created a debate referred to as the Hertha Debate. The two foremost questions was to abolish coverture for unmarried women, and for the state to provide women an equivalent to a university. Both questions were met: in 1858, a reform granted unmarried women the right to apply for legal majority by a simple procedure, and in 1861, Högre lärarinneseminariet was founded as a "Women's University". In 1859, the first women's magazine in Sweden and the Nordic countries, the Tidskrift för hemmet, was founded by Sophie Adlersparre and Rosalie Olivecrona. This has been referred to as the starting point of a women's movement in Sweden.

The organized women's movement begun in 1873, when Married Woman's Property Rights Association was co-founded by Anna Hierta-Retzius and Ellen Anckarsvärd. The prime task of the organization was to abolish coverture. In 1884, Fredrika Bremer Association was founded by Sophie Adlersparre to work for the improvement in women's rights. The second half of the 19th century saw the creation of several women's rights organisations and a considerable activity within both active organization as well as intellectual debate. The 1880s saw the so-called Sedlighetsdebatten, where gender roles were discussed in literary debate in regards to sexual double standards in opposed to sexual equality. In 1902, finally, the National Association for Women's Suffrage was founded.

In 1919–1921, women's suffrage was finally introduced. The women suffrage reform was followed by the Behörighetslagen of 1923, in which males and females were formally given equal access to all professions and positions in society, the only exceptions being military and priesthood positions.[40] The last two restrictions were removed in 1958, when women were allowed to become priests, and in a series of reforms between 1980 and 1989, when all military professions were opened to women.[41]

Switzerland

The Swiss women's movement started to form after the introduction of the Constitution of 1848, which explicitly excluded women's rights and equality. However, the Swiss women's movement was long prevented from being efficient by the split between French- and German speaking areas, which restricted it to local activity. This split created a long lasting obstacle for the national Swiss women's movement. However, it did play an important role in the international women's movement, when Marie Goegg-Pouchoulin founded the first international women's movement in the world, the Association Internationale des Femmes, in 1868.[42]

In 1885, the first national women's organisation, the Schweizer Frauen-Verband, was founded by Elise Honegger. It soon split, but in 1888, the first permanent, national women's organisation was finally founded in the Schweizerischen Gemeinnützigen Frauenverein (SGF), which became an umbrella organisation for the Swiss women's movement. From 1893 onward, a local women's organisation, the Frauenkomitee Bern, also functioned as a channel between the Federal government and the Swiss women's movements. The question of women's suffrage in Switzerland was brought forward by the Schweizerischer Frauenvereine from 1899, and by the Schweizerischer Verband für Frauenstimmrecht from 1909, which were to become the two main suffrage organisations of many in Switzerland.

The Swiss suffrage movement had struggled for equality in their society for decades until the early 1970s; this wave of feminism also included enfranchisement. October 31, 1971, Swiss women were granted the right to vote in political elections. According to Lee Ann Banaszak the main reasons for lack of success in women's suffrage for Swiss women was due to the differences in mobilization of members into suffrage organizations, financial resources of the suffrage movements, alliances formed with other political actors, and the characteristics of the political systems. Therefore, the success of the Swiss women's suffrage movement was heavily affected by the resources and political structures. "The Swiss movement had to operate in a system where decisions were made carefully by a constructed consensus and where opposition parties never launched an electoral challenge that might of prodded governing parties into action." This explains how the closed legislative process made it way more difficult for suffrage activists to participate in, or even track women's voting rights. Swiss suffrage also lacked strong allies when it came from their struggle to vote in political elections.[43] The 1970s saw a turning point for Swiss feminist movements, and they began to steadily make more progress in their struggle for equality to present day.

United Kingdom

The early feminist reformers were unorganized, and including prominent individuals who had suffered as victims of injustice. This included individuals such as Caroline Norton whose personal tragedy where she was unable to obtain a divorce and was denied access to her three sons by her husband, led her to a life of intense campaigning which successfully led to the passing of the Custody of Infants Act 1839 and the introduction of the Tender years doctrine for child custody arrangement.[44][45][46] The Act gave married women, for the first time, a right to their children. However, because women needed to petition in the Court of Chancery, in practice, few women had the financial means to petition for their rights.[47]

The first organized movement for English feminism was the Langham Place Circle of the 1850s, which included among others Barbara Bodichon (née Leigh-Smith) and Bessie Rayner Parkes.[48] The group campaigned for many women's causes, including improved female rights in employment, and education. It also pursued women's property rights through its Married Women's Property Committee. In 1854, Bodichon published her Brief Summary of the Laws of England concerning Women,[49] which was used by the Social Science Association after it was formed in 1857 to push for the passage of the Married Women's Property Act 1882.[50] In 1858, Barbara Bodichon, Matilda Mary Hays and Bessie Rayner Parkes established the first feminist British periodical, the English Woman's Journal,[51] with Bessie Parkes the chief editor. The journal continued publication until 1864 and was succeeded in 1866 by the Englishwoman's Review edited until 1880 by Jessie Boucherett which continued publication until 1910. Jessie Boucherett and Adelaide Anne Proctor joined the Langham Place Circle in 1859. The group was active until 1866. Also in 1859, Jessie Boucherett, Barbara Bodichon and Adelaide Proctor formed the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women to promote the training and employment of women.[52] The society is one of the earliest British women's organisations, and continues to operate as the registered charity Futures for Women.[53] Helen Blackburn and Boucherett established the Women's Employment Defence League in 1891, to defend women's working rights against restrictive employment legislation.[54] They also together edited the Condition of Working Women and the Factory Acts in 1896. In the beginning of the 20th century, women's employment was still predominantly limited to factory labor and domestic work. During World War I, more women found work outside the home. As a result of the wartime experience of women in the workforce, the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 opened professions and the civil service to women, and marriage was no longer a legal barrier to women working outside the home.

In 1918, Marie Stopes published the very influential Married Love,[55] in which she advocated gender equality in marriage and the importance of women's sexual desire. (Importation of the book into the United States was banned as obscene until 1931.)

The Representation of the People Act 1918 extended the franchise to women who were at least 30 years old and they or their husbands were property holders, while the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918 gave women the right to sit in Parliament, although it was only slowly that women were actually elected. In 1928, the franchise was extended to all women over 21 by the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928, on an equal basis to men.[56]

Many feminist writers and women's rights activists argued that it was not equality to men which they needed but a recognition of what women need to fulfill their potential of their own natures, not only within the aspect of work but society and home life too. Virginia Woolf produced her essay A Room of One's Own based on the ideas of women as writers and characters in fiction. Woolf said that a woman must have money and a room of her own to be able to write.

It ought to be recognized that the early British feminist movement was deeply intertwined with the British imperial project and an essential arm of it. Contemporary writers like Mona Caird asserted that women deserved representation in the "councils of the nation" as defenders of the white race and its supremacy.[57] In order to achieve status and value as women, these feminists framed themselves as the benevolent feminine liberators of the "foreign woman". Antoinette Burton writes that rather than upending Victorian gendered assumptions, "early feminist theorist used [them] to justify female involvement in the public sphere by claiming that the woman's moral attributes was crucial to social improvement."[58] Burton calls to our attention that women exerted real power over their male counterparts by making claims to the very moral assumptions that bound them to the home. It would be naïve to suggest that these women were not complicit in or did not contribute to imperial oppression abroad, but what is missed by previous treatments of feminisms and feminist movements is the diversity and flexibility of power relationships that navigated the superstructure of the moral order. The place of sex and gender in Victorian society was more diverse and plural than Victorian morality imagined for itself.

United States

The beginning of first-wave Feminism in the United States is traditionally marked by the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848; however this event was empowered by women becoming increasingly politically active in the years leading up to 1848 through the Abolitionist Movement and Temperance Movement and activists began to have their voices heard. Some of these early activists include, Sojourner Truth, Elizabeth Blackwell, Jane Addams, and Dorothy Day.[59] The first wave of feminism was primarily led by white women in the middle class, and it was not until the second wave of feminism that women of color began developing a voice.[60] The term Feminism was created like a political illustrated ideology at that period. Feminism emerged by the speech about the reform and correction of democracy based on equalitarian conditions.[61]

Leading up to the early 19th century, white women in Colonial America were socially expected to remain domestically confined and their property and political rights were severely limited and controlled by marriage. Social expectations preceding and following the American Revolution did not encourage women to be politically active or seek formal education.[62] Women were also expected to pass on and teach Christian values to their children. Thus the impact of alcohol on many men post Civil War became not only a moral motivation for women to become active in the Temperance Movement but also a way to exert control over finances and property. Communities of women in churches congregated and rallied outside of the home for the cause.[63] The most direct and impactful movement on first-wave feminism was the Abolitionist Movement. Black men and women had been fighting for rights during and before the Temperance Movement. White women began to identify themselves with the struggle for rights and became involved in the abolition of slavery.

Judith Sargent Murray published the early and influential essay On the Equality of the Sexes in 1790, blaming poor standards in female education as the root of women's problems.[64] However, scandals surrounding the personal lives of English contemporaries Catharine Macaulay and Mary Wollstonecraft pushed feminist authorship into private correspondence from the 1790s through the early decades of the nineteenth century.[65] Feminist essays from John Neal in Blackwood's Magazine and The Yankee in the 1820s filled an intellectual gap between Murray and the leaders of the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention,[66] which is generally considered the beginning of the first wave of feminism.[67] As a male writer insulated from many common forms of attack against female feminist thinkers, Neal's advocacy was crucial to bringing feminism back into the American mainstream.[68]

Woman in the Nineteenth Century by Margaret Fuller has been considered the first major feminist work in the United States and is often compared to Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.[69] Prominent leaders of the feminist movement in the United States include Lucretia Coffin Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone, and Susan B. Anthony; Anthony and other activists such as Victoria Woodhull and Matilda Joslyn Gage made attempts to cast votes prior to their legal entitlement to do so, for which many of them faced charges. Other important leaders included several women who dissented against the law in order to have their voices heard, (Sarah and Angelina Grimké), in addition to other activists such as Carrie Chapman Catt, Alice Paul, Sojourner Truth, Ida B. Wells, Margaret Sanger and Lucy Burns.[70]

First-wave feminism involved a wide range of women, some belonging to conservative Christian groups (such as Frances Willard and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union), others such as Matilda Joslyn Gage of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) resembling the radicalism of much of second-wave feminism. The creation of these organizations was a direct result of the Second Great Awakening, a religious movement in the early 19th century, that inspired female reformers in the United States.[71]

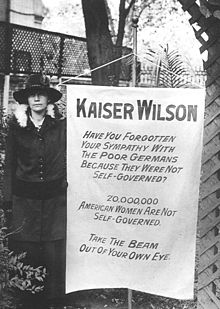

The majority of first-wave feminists were more moderate and conservative than radical or revolutionary—like the members of the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) they were willing to work within the political system and they understood the clout of joining with sympathetic men in power to promote the cause of suffrage. The limited membership of the NWSA was narrowly focused on gaining a federal amendment for women's suffrage, whereas the AWSA, with ten times as many members, worked to gain suffrage on a state-by-state level as a necessary precursor to federal suffrage. The NWSA had broad goals, hoping to achieve a more equal social role for women, but the AWSA was aware of the divisive nature of many of those goals and instead chose to focus solely on suffrage. The NWSA was known for having more publicly aggressive tactics (such as picketing and hunger strikes) whereas the AWSA used more traditional strategies like lobbying, delivering speeches, applying political pressure, and gathering signatures for petitions.[72]

During the first wave, there was a notable connection between the slavery abolition movement and the women's rights movement. Frederick Douglass was heavily involved in both movements and believed that it was essential for both to work together in order to attain true equality in regards to race and sex.[73] Different accounts of the involvement of African-American women in the Women's Suffrage Movement are given. In a 1974 interview, Alice Paul notes that a compromise was made between southern groups to have white women march first, then men, then African-American women.[74] In another account by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), difficulties in segregating women resulted in African-American women marching with their respective States without hindrance.[75] Among them was Ida B. Wells-Barnett, who marched with the Illinois delegation.

The end of the first wave is often linked with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (1920), granting women the right to vote. This was the major victory of the movement, which also included reforms in higher education, in the workplace and professions, and in health care. Women started serving on school boards and local bodies, and numbers kept increasing. This period also saw more women gaining access to higher education. In 1910, "women were attending many leading medical schools, and in 1915, the American Medical Association began to admit women members."[76] A Matrimonial Causes Act 1923 gave women the right to the same grounds for divorce as men. The first wave of feminists, in contrast to the second wave, focused very little on the subjects of abortion, birth control, and overall reproductive rights of women. Though she never married, Anthony published her views about marriage, holding that a woman should be allowed to refuse sex with her husband; the American woman had no legal recourse at that time against rape by her husband.[77]

The rise in unemployment during the Great Depression which started in the 1920s hit women first, and when the men also lost their jobs there was further strain on families. Many women served in the armed forces during World War II, when around 300,000 American women served in the navy and army, performing jobs such as secretaries, typists and nurses.

State laws

The American states are separate sovereigns,[78] with their own state constitutions, state governments, and state courts. All states have a legislative branch which enacts state statutes, an executive branch that promulgates state regulations pursuant to statutory authorization, and a judicial branch that applies, interprets, and occasionally overturns both state statutes and regulations, as well as local ordinances. States retain plenary power to make laws covering anything not preempted by the federal Constitution, federal statutes, or international treaties ratified by the federal Senate. Normally, state supreme courts are the final interpreters of state institutions and state law, unless their interpretation itself presents a federal issue, in which case a decision may be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court by way of a petition for writ of certiorari.[79] State laws have dramatically diverged in the centuries since independence, to the extent that the United States cannot be regarded as one legal system as to the majority of types of law traditionally under state control, but must be regarded as 50 separate systems of tort law, family law, property law, contract law, criminal law, and so on.[80]

Marylynn Salmon argues that each state developed different ways of dealing with a variety of legal issues pertaining to women, especially in the case of property laws.[81] In 1809, Connecticut was the first state to pass a law allowing women to write wills.

In 1860, New York passed a revised Married Women's Property Act which gave women shared ownership of their children, allowing them to have a say in their children's wills, wages, and granting them the right to inherit property.[82] Further advances and setbacks were experienced in New York and other states, but with each new win the feminists were able to use it as an example to apply more leverage on unyielding legislative bodies.

White feminism

Imperialism

Anxiety in the United States over the moral degeneracy and temptation of American men in the Philippines inspired women's involvement in the politics of the colonial government. An article published in The Washington Post in 1900 describes the Philippines as an environment where relatively permissive conceptions of morality caused white men to "lose all notions of right and wrong". It was said that white men "disgraced the offices to which they had been appointed", and that, despite having left their homes "with records that were above reproach", they were "degenerated by the conditions of their new existence". Away from the social pressures imposed by their community, they did not possess the strength of moral character or principle needed to maintain the "social discipline".[83]

White women feminists, in this historical context, asserted their superiority over white men and brown women. They have in been criticized by modern women writers of color like Valerie Amos and Pratibha Parmar.[84]

Inequality

In the First Wave context, there are two different fights for the equal rights of white women and black women. White women were fighting for rights equal to white men in society. They wanted to correct the discrepancy in education, professional, property, economic, and voting rights. They also fought for birth control and abortion freedom. Black women, on the other hand, were facing both racism and sexism, contributing to an uphill struggle for black feminists. While White women could not vote, black women and men could not vote. Mary J. Garrett who founded a group consisting of hundreds of Black women in New Orleans, said that black women strove for education and protection. It is true that "black women in higher education are isolated, underutilized, and often demoralized,"[85] and they fought together against this. They were fighting against "exploitation by White men" and they wanted to "lead a virtuous and industrious life."[86] Black women were also fighting for their husbands, families, and overall equality and freedom of their civil rights. Racism restricted white and black women from coming together to fight for common societal transformation.[87]

First Wave Feminism in the United States did not chronicle the contributions of black women to the same degree as white women. Activists, including Susan B. Anthony and other feminist leaders preached for equality between genders; however, they disregarded equality between a number of other issues, including race. This allowed for white women to gain power and equality relative to white men, while the social disparity between white and black women increased. The exclusion aided the growing prevalence of White supremacy, specifically white feminism while actively overlooking the severity of impact black feminists had on the movement.[88][89]

Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were abolitionists but they did not advocate for universal suffrage. They did not want black men to be granted the right to vote before white women. The National American Woman Suffrage Association was created to distinguish themselves from advocating for black men to vote.[87] The Fifteenth Amendment states no person should be denied the right to vote based on race. Anthony and Stanton opposed passage of the amendment unless it was accompanied by a Sixteenth Amendment that would guarantee suffrage for women. Otherwise, they said, it would create an "aristocracy of sex" by giving constitutional authority to the belief that men were superior to women. The new proposal of this amendment was named the "Anthony Amendment".[90] Stanton once said that allowing black men to vote before women "creates an antagonism between black men and all women that will culminate in fearful outrages on womanhood".[91] Anthony stated, she would "cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work for or demand the ballot for the negro and not the woman".[92] Mary Church Terrell exclaimed in 1904 that, "My sisters of the dominant race, stand up not only for the oppressed sex, but also for the oppressed race!"[93] The National American Woman Suffrage Association sustained the inequalities between black and white women and also limited their ability to contribute.[94]

Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass together formed the American Equal Rights Association, advocating for equality between both gender and sex. In 1848, Frederick Douglass was asked to speak by Susan B. Anthony at a convention in Seneca Falls, New York. Frederick Douglass was an active supporter.[95] Later, Douglass was not permitted to attend an Atlanta, Georgia NAWSA convention. Susan B. Anthony exclaimed, "I did not want to subject him to humiliation, and I did not want anything to get in the way of bringing the Southern white women into our suffrage association, now that their interest had been awakened".[96] Douglass opposed the fact that Cady and Anthony were extremely unsupportive of black voting rights.[97] White women condoned racism at the cost of black women if it meant benefitting and more support of the white suffrage movement.[98][89]

Institutional racism

It was not just through personal racism that black women were excluded from feminists movements; institutional racism prevented many women from having an avid say and stance. It is important to consider the history of black women's labor in the economic, social and political history of America and when orienting the role of black women in first-wave feminism because that history indicates an entirely different experience between black and white women. Black Americans regardless of gender face a violent history of oppression that exploited, abused and commoditized the body for labor as an essential aspect of the early development and success of the United States' economy. Black women were essential to maintaining the mass labor of enslaved people because they could have children that would later become subject to forced labor as well. This uniquely ties black women to the foundation of the United States' economic success. Black women thusly face oppression based on class, race as well as gender that means their interactions with the legal, social, political, educational and economic institutions that feminism aims to change is different from how white women interact with those same systems. The goal of first-wave feminism being mainly to resolve legal issues, chiefly to secure voting rights, only considered the needs of white high class women. First-wave feminism entirely mimicked the racial hierarchy that maintained the power dynamics that exploit black women and completely alienated black women from the feminist movement.[99] The National American Woman Suffrage Association, established by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton[100] did not invite black women to attend specific meetings, excluding them entirely. Feminist and women's suffrage conventions held in Southern states, where black women were a dominant percentage of the population, were segregated.[87]

Institutional racism excluded black women in the March on Washington in 1913. Black women were asked to march separately, together, at the back of the parade.[94] They were forced to be made absent which can be seen in the lack of photographs and media of black women marching in the parade. White women did not want black women associated with their movement because they believed white women would disaffiliate themselves from an integrated group and create a segregated, more powerful one.[92]

Sojourner Truth's "Ain't I a Woman?"

Despite participating and contributing a great deal to all feminists movements, black women were rarely recognized. Mary McLeod Bethune said that the world was unable to accept all of the contributions black women have made. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton together wrote the History of Woman Suffrage published in 1881. The book failed to give adequate recognition to the black women who were equally responsible for the change in United States history.[101] Sojourner Truth became an influential advocate for the women's rights movement. In 1851 she delivered her "Ain't I a Woman" speech at the women's rights convention in Akron, Ohio. Black women at this point were beginning to become empowered and assertive, speaking out on the disproportionate inequalities. Truth speaks of how she, and other women, are capable of working as much as men, after having thirteen children. This speech was one of the ways white and black women became closer to working towards fighting for the same thing. Sojourner Truth's speech was originally documented by Marius Robinson, a good friend of hers, who was present at the women's rights convention. Sojourner voiced her thoughts on the civil rights of women. In 1863, twelve years after she delivered the speech Frances Gage published her recollection of Sojourners speech on that day. Gage changed a majority of Sojourner's words and made her appear as if she had a southern slave dialect which she in fact did not as shown in Robinson's accurate version. Gage wrote phrases such as "chillen, whar dar's so much racket dar must be som'ting out o'kilter."[102] when Sojourner actually said "May I say a few words? I want to say a few words about this matter."[103] Thought this speech was a huge stepping stone for the women's movement, it was still evident who the movement was focused on. Truth made a speech at the American Equal Rights Association in New York in 1867. In the speech, she said, "If colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs, you see the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before."[104] Her speeches brought attention to the movement, for black women, but also for white. Although private lives continued to be segregated, feminist coalitions became integrated. Two separate reasons aided integration in the feminist movement. Paula Giddings wrote that the two fights against racism and sexism could not be separated. Gerda Lerner wrote that black women demonstrated they too were fully capable of fighting and creating change for equality.[101]

Timeline

- 1809

- US, Connecticut: Married women were allowed to execute wills.[105]

- 1810

- Sweden: The informal right of an unmarried woman to be declared of legal majority by royal dispensation was officially confirmed by parliament.[106]

- 1811

- Austria: Married women were granted separate economy and the right to choose their professions.[107]

- Sweden: Married businesswomen were granted the right to make decisions about their own affairs without their husband's consent.[108]

- 1821

- US, Maine: Married women were allowed to own and manage property in their own name during the incapacity of their spouse.[109]

- 1827

- Brazil: The first elementary schools for girls and the profession of school teacher were opened.[110]

- 1829

- India: Sati was banned.[111][112][113] Sati scholars, however, disagree about the extent to which the prohibition of sati reflected concerns about women's rights.[citation needed]

- Sweden: Midwives were allowed to use surgical instruments, which were unique in Europe at the time and gave them surgical status.[114]

- 1832

- Brazil: Dionísia Gonçalves Pinto, under the pseudonym Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta, published her first book, and the first in Brazil to deal with women's intellectual equality and their capacity and right to be educated and participate in society on an equal basis with men, which was Women's rights and men's injustice.[115] It was a translation of Woman not Inferior to Man, often attributed to Mary Wortley Montagu.[116][117]

- 1833

- US, Ohio: The first co-educational American university, Oberlin College, was founded.[118]

- Guatemala: Divorce was legalized; this was rescinded in 1840 and reintroduced in 1894.[119]

- 1835

- US, Arkansas: Married women were allowed to own (but not control) property in their own name.[120]

- 1838

- US, Kentucky: Kentucky gave school suffrage (the right to vote at school meetings) to widows with children of school age.[121]

- US, Iowa: Iowa was the first U.S. state to allow sole custody of a child to its mother in the event of a divorce.[121]

- Pitcairn Islands: The Pitcairn Islands granted women the right to vote.[122]

- 1839

- US, Mississippi: Mississippi was the first U.S. state that gave married women limited property rights.[121]

- United Kingdom: The Custody of Infants Act 1839 made it possible for divorced mothers to be granted custody of their children under seven, but only if the Lord Chancellor agreed to it, and only if the mother was of good character.[123]

- US, Mississippi: The Married Women's Property Act 1839 granted married women the right to own (but not control) property in their own name.[124]

- 1840

- 1841

- Bulgaria: The first secular girls school in Bulgaria was opened, making education and the profession of teacher available for women.[125]

- 1842

- Sweden: Compulsory elementary school for both sexes was introduced.[126]

- 1844

- US, Maine: Maine was the first U.S. state that passed a law to allow married women to own separate property in their own name (separate economy) in 1844.[127]

- US, Maine: Maine passed Sole Trader Law which granted married women the ability to engage in business without the need for their husbands' consent.[121]

- US, Massachusetts: Married women were granted separate economy.[128]

- 1845

- Sweden: Equal inheritance for sons and daughters (in the absence of a will) became law.[129]

- US, New York: Married women were granted patent rights.[130]

- 1846

- Sweden: Trade- and crafts works professions were opened to all unmarried women.[131]

- 1847

- Costa Rica: The first high school for girls opened, and the profession of teacher was opened to women.[132]

- 1848

- US, State of New York: Married Women's Property Act grant married women separate economy.[133]

- US, on June 14–15, third-party presidential candidate Gerrit Smith made women's suffrage a plank in the Liberty Party platform.[134]

- US, State of New York: A women's rights convention called the Seneca Falls Convention was held in July. It was the first American women's rights convention.[135]

- 1849

- US: Elizabeth Blackwell, born in England, became the first female medical doctor in American history.[136]

- 1850

- United Kingdom: The first organized movement for English feminism was the Langham Place Circle of the 1850s, including among others Barbara Bodichon (née Leigh-Smith) and Bessie Rayner Parkes.[48] They also campaigned for improved female rights in employment, and education.[137]

- Haiti: The first permanent school for girls was opened.[138]

- Iceland: Equal inheritance for men and women was required.[139]

- US, California: Married Women's Property Act granted married women separate economy.[140]

- US, Wisconsin: The Married Women's Property Act granted married women separate economy.[140]

- US, Oregon: Unmarried women were allowed to own land.[107]

- The feminist movement began in Denmark with the publication of the feminist book Clara Raphael, Tolv Breve, meaning "Clara Raphael, Twelve Letters," by Mathilde Fibiger.[141][142]

- 1851

- Guatemala: Full citizenship was granted to economically independent women, but this was rescinded in 1879.[143]

- Canada, New Brunswick : Married women were granted separate economy.[144]

- 1852

- US, New Jersey: Married women were granted separate economy.[128]

- 1853

- Colombia: Divorce was legalized; this was rescinded in 1856 and reintroduced in 1992.[119]

- Sweden: The profession of teacher at public primary and elementary school was opened to both sexes.[145]

- 1854

- Norway: Equal inheritance for men and women was required.[107]

- US, Massachusetts: Massachusetts granted married women separate economy.[140]

- Chile: The first public elementary school for girls was opened.[146]

- 1855

- US, Iowa: The University of Iowa became the first coeducational public or state university in the United States.[147]

- US, Michigan: Married women were granted separate economy.[125]

- 1857

- Denmark: Legal majority was granted to unmarried women.[107]

- Denmark: A new law established the right of unmarried women to earn their living in any craft or trade.[142]

- United Kingdom: The Matrimonial Causes Act 1857 enabled couples to obtain a divorce through civil proceedings.[148][149]

- Netherlands: Elementary education was made compulsory for both girls and boys.[150]

- Spain: Elementary education was made compulsory for both girls and boys.[151]

- US, Maine: Married women were granted the right to control their own earnings.[128]

- 1858

- Russia: Gymnasiums for girls were opened.[152]

- Sweden: Legal majority was granted to unmarried women if applied for; automatic legal majority was granted in 1863.[129]

- 1859

- Canada West: Married women were granted separate economy.[144]

- Denmark: The post of teacher at public school was opened to women.[153]

- Russia: Women were allowed to audit university lectures, but this was retracted in 1863.[152]

- Sweden: The posts of college teacher and lower official at public institutions were opened to women.[154]

- US, Kansas: The Married Women's Property Act granted married women separate economy.[140]

- 1860

- US, New York: New York passed a revised Married Women's Property Act which gave women shared legal custody of their children, allowing them to have a say in their children's wills, wages, and granting them the right to inherit property.[82]

- 1861

- South Australia: South Australia granted property-owning women the right to vote in local elections.[155]

- US, Kansas: Kansas gave school suffrage to all women. Many U.S. states followed before the start of the 20th century.[121]

- 1862

- Sweden: Restricted local suffrage was granted to women in Sweden. In 1919 suffrage was granted with restrictions, and in 1921 all restrictions were lifted.[156]

- 1863

- Finland: In 1863, taxpaying women were granted municipal suffrage in the country side, and in 1872, the same reform was given to the cities.[157]

- 1869

- United Kingdom: The UK granted women the right to vote in local elections.[158]

- US, Wyoming: the Wyoming territories grant women the right to vote, the first part of the US to do so.[159]

- 1870

- US, Utah: The Utah territory granted women the right to vote, but it was revoked by Congress in 1887 as part of a national effort to rid the territory of polygamy. It was restored in 1895, when the right to vote and hold office was written into the constitution of the new state.[160]

- United Kingdom: The Married Women's Property Act was passed in 1870 and expanded in 1874 and 1882, giving women control over their own earnings and property.[127]

- 1871

- Denmark: In 1871, the worlds very first Women's Rights organization was founded by Mathilde Bajer and her husband Frederik Bajer, called Danish Women's Society (or Dansk Kvindesamfund. It still exists to this day).

- Netherlands: First female academic student Aletta Jacobs enrolls at a Dutch university (University of Groningen).

- 1872

- Finland: In 1872, taxpaying women were granted municipal suffrage in the cities.[157]

- 1881

- Isle of Man: The right to vote was extended to unmarried women and widows who owned property, and as a result 700 women received the vote, comprising about 10% of the Manx electorate.[161]

- 1884

- Canada: Widows and spinsters were the first women granted the right to vote within municipalities in Ontario, with the other provinces following throughout the 1890s.[162]

- 1886

- US: All but six U.S. states allowed divorce on grounds of cruelty.[121]

- Korea: Ewha Womans University, Korea's first educational institute for women, was founded in 1886 by Mary F. Scranton, an American missionary of the Methodist Episcopal Church.[163]

- 1891

- Australia: The New South Wales Womanhood Suffrage League was founded.[164]

- 1893

- US, Colorado: Colorado granted women the right to vote.[165]

- New Zealand: New Zealand became the first self-governing country in the world in which all women had the right to vote in parliamentary elections.[166]

- Cook Islands: The Cook Islands granted women the right to vote in island councils and a federal parliament.[167]

- 1894

- South Australia: South Australia granted women the right to vote.[167]

- United Kingdom: The United Kingdom extended the right to vote in local elections to married women.[168]

- 1895

- US: Almost all U.S. states had passed some form of Sole Trader Laws, Property Laws, and Earnings Laws, granting married women the right to trade without their husbands' consent, own and/or control their own property, and control their own earnings.[121]

- 1896

- Argentina: A group of anarcha-feminist women, headed by Virginia Bolten, publish La Voz de la Mujer, one of the first feminist newspapers of Latin America.[169]

- US, Idaho: Idaho granted women the right to vote.[170]

- 1900

- Western Australia: Western Australia granted women the right to vote.[171]

- Belgium: Legal majority was granted to unmarried women.[172]

- Egypt: A school for female teachers was founded in Cairo.[173]

- France: Women were allowed to practice law.[174]

- Korea: The post office profession was opened to women.[175]

- Tunisia: The first public elementary school for girls was opened.[173]

- Japan: The first women's university was opened.[176]

- Baden, Germany: Universities opened to women.[177]

- Sweden: Maternity leave was granted for female industrial workers.

- 1901

- Bulgaria: Universities opened to women.[178]

- Cuba: Universities opened to women.[179]

- Denmark: Maternity leave was granted for all women.[180]

- Sweden: The first Swedish law regarding parental leave was instituted in 1900. This law only affected women who worked as wage-earning factory workers and simply required that employers not allow women to work in the first four weeks after giving birth.[181]

- Commonwealth of Australia: The First Parliament was not elected with a uniform franchise. The voting rights were based on existing franchise laws in each of the States. Thus, in South Australia and Western Australia women had the vote, in South Australia Aborigines (men and women) were entitled to vote and in Queensland and Western Australia Aborigines were explicitly denied voting rights.[182][183]

- 1902

- China: Foot binding was outlawed in 1902 by the imperial edicts of the Qing Dynasty, the last dynasty in China, which ended in 1911.[184]

- El Salvador: Married women were granted separate economy.[185]

- El Salvador: Legal majority was granted to married women.[185]

- New South Wales: New South Wales granted women the right to vote in state elections.[186]

- United Kingdom: A delegation of women textile workers from Northern England presented a petition to Parliament with 37,000 signatures demanding votes for women.[187]

- 1903

- Bavaria, Germany: Universities opened to women.[177]

- Sweden: Public medical offices opened to women.[188]

- Australia: Tasmania granted women the right to vote.[189]

- United Kingdom: The Women's Social and Political Union was founded.[187]

- 1904

- Nicaragua: Married women were granted separate economy.[185]

- Nicaragua: Legal majority was granted to married women.[185]

- Württemberg, Germany: Universities opened to women.[177]

- United Kingdom: The suffragette Dora Montefiore refused to pay her taxes because women could not vote.[190]

- 1905

- Australia: Queensland granted women the right to vote.[191]

- Iceland: Educational institutions opened to women.[107]

- Russia: Universities opened to women.[107]

- United Kingdom: On October 10, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney became the first women to be arrested in the fight for women's suffrage.[190]

- 1906

- Finland granted women the right vote.[192] It was the first country in Europe to do so.[193]

- Honduras: Married women were granted separate economy.[185]

- Honduras: Legal majority was granted to married women.[185]

- Honduras: Divorce was legalized[119]

- Korea: The profession of nurse was allowed for women.[194]

- Nicaragua: Divorce was legalized.[119]

- Sweden : Municipal suffrage, since 1862 granted to unmarried women, was granted to married women.[195]

- Saxony, Germany: Universities opened to women.[177]

- United Kingdom: A delegation of women from both the Women's Social and Political Union and the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies met with the Prime Minister, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman.[187]

- United Kingdom: The word suffragette, intended as an insult to women in the Women's Social and Political Union, was used for the first time, by the Daily Mail.[193]

- United Kingdom: The National Federation of Women Workers was established by Mary Reid MacArthur.[193]

- 1907

- France: Married women were given control of their income.[196]

- France: Women were allowed guardianship of children.[174]

- Norway: Women were granted the right to stand for election, although this was subject to restrictions until 1913.[197]

- Finland: The first female members of parliament in world history were elected in Finland in 1907.[192]

- Uruguay: Divorce was legalized.[198]

- United Kingdom The National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies organized its first national demonstration, which became known as the "Mud March" because of the terrible weather at the time.[193]

- United Kingdom: Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and her husband Frederick launched the suffragette newspaper Votes for Women.

- United Kingdom: The Women's Freedom League was formed when Charlotte Despard and others broke away from the Women's Social and Political Union.[193]

- United Kingdom: The Qualification of Women Act 1907 allowed women to be elected as mayors and to borough and city councils.[193]

- 1908

- Belgium: Women were allowed to act as legal witnesses in court.[107]

- Denmark: Unmarried women were made legal guardians of their children.[180]

- Peru: Universities opened to women.[199]

- Prussia, Alsace-Lorraine and Hesse, Germany: Universities opened to women.[177]

- Denmark: Denmark granted women over 25 the right to vote in local elections.[200]

- Australia: Victoria granted women the right to vote in state elections.[201]

- United Kingdom: On January 17, suffragettes chained themselves to the railings of 10 Downing Street.[193] Emmeline Pankhurst was imprisoned for the first time.[193] The Women's Social and Political Union also introduced their stone-throwing campaign.[193]

- 1909

- Sweden: Women were granted eligibility to municipal councils.[195]

- Sweden: The phrase "Swedish man" was removed from the application forms to public offices and women were thereby approved as applicants to most public professions.[188]

- Mecklenburg, Germany: Universities opened to women.[177]

- United Kingdom: In July, Marion Wallace Dunlop became the first imprisoned suffragette to go on a hunger strike. As a result, force-feeding was introduced.[193]

- 1910

- Argentina: Elvira Rawson de Dellepiane founded the Feminist Center (Spanish: Centro Feminista) in Buenos Aires, joined by a group of prestigious women.[202]

- Denmark: The Socialist International, meeting in Copenhagen, established a Women's Day, international in character, to honor the movement for women's rights and to assist in achieving universal suffrage for women.[203]

- US, Washington: Washington granted women the right to vote.[204]

- Ecuador: Divorce was legalized.[119]

- United Kingdom: November 18 was "Black Friday", when the suffragettes and police clashed violently outside Parliament after the failure of the first Conciliation Bill. Ellen Pitfield, one of the suffragettes, later died from her injuries.[190]

- 1911

- United Kingdom: Dame Ethel Smyth composed "The March of the Women", the suffragette song.[190]

- Portugal: Legal majority was granted to married women (rescinded in 1933.)[205]

- Portugal: Divorce was legalized.[205]

- US, California: California granted women the right to vote.[206]

- Austria, Denmark, Germany and Switzerland: International Women's Day was marked for the first time in Austria, Denmark, Germany and Switzerland on 19 March. More than one million women and men attended IWD rallies campaigning for women's rights to work, vote, be trained, hold public office and be free from discrimination.[207]

- South Africa: Olive Schreiner published Women and Labor.[190]

- 1912

- US, Oregon, Kansas, Arizona: Oregon, Kansas, and Arizona granted women the right to vote.[208]

- United Kingdom: Sylvia Pankhurst established her East London Federation of Suffragettes.[190]

- 1913

- Russia: In 1913, Russian women observed their first International Women's Day on the last Sunday in February. Following discussions, International Women's Day was transferred to 8 March and this day has remained the global date for International Women's Day ever since.[207]

- US, Alaska: Alaska granted women the right to vote.[208]

- Norway: Norway granted women the right to vote.[209]

- Japan: Public universities opened to women.[210]

- United Kingdom: The suffragette Emily Davison was killed by the King's horse at The Derby.[190]

- United Kingdom: 50,000 women taking part in a pilgrimage organized by the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies arrived in Hyde Park on July 26.[190]

- 1914

- Russia: Married women were allowed their own internal passport.[152]

- US, Montana, Nevada: Montana and Nevada granted women the right to vote.[208]

- United Kingdom: The suffragette Mary Richardson entered the National Gallery and slashed the Rokeby Venus.[190]

- 1915

- Denmark: Denmark granted women the right to vote.[200]

- Iceland: Iceland granted women the right to vote, subject to conditions and restrictions.[197]

- US: In 1915, the American Medical Association began to admit women as members.[76]

- Wales: The first Women's Institute in Britain was founded in North Wales at Llanfairpwll.[190]

- 1916

- Canada: Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan granted women the right to vote.[211]

- US: Margaret Sanger opened America's first birth control clinic in 1916.[212]

- United Kingdom: The Cat and Mouse Act was introduced for suffragettes who refused to eat.[190]

- 1917

- Cuba: Married women were granted separate economy.[185]

- Cuba: Legal majority was granted to married women.[185]

- Netherlands: Women were granted the right to stand for election.[213]

- Mexico: Legal majority for married women.[185]

- Mexico: Divorce was legalized.[185]

- US, New York: New York granted women the right to vote.[208]

- Belarus: Belarus granted women the right to vote.[214]

- Russia: The Russian SFSR granted women the right to vote.[215]

- 1918

- Cuba: Divorce was legalized.[119]

- Russia: The first Constitution of the new Soviet State (the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic) declared that "women have equal rights to men."[216]

- Thailand: Universities opened to women.[217]

- United Kingdom: In 1918, Marie Stopes, who believed in equality in marriage and the importance of women's sexual desire, published Married Love,[55] a sex manual that, according to a survey of American academics in 1935, was one of the 25 most influential books of the previous 50 years, ahead of Relativity by Albert Einstein, Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler, Interpretation of Dreams by Sigmund Freud and The Economic Consequences of the Peace by John Maynard Keynes.[218]

- US, Michigan, South Dakota, Oklahoma: Michigan, South Dakota, and Oklahoma granted women the right to vote.[208]

- Austria: Austria granted women the right to vote.[211]

- Canada: Canada granted women the right to vote on the federal level (the last province to enact women's suffrage was Quebec in 1940.)[219]

- United Kingdom: The Representation of the People Act was passed which allowed women over the age of 30 who met a property qualification to vote. Although 8.5 million women met this criterion, it only represented 40 per cent of the total population of women in the UK. The same act extended the vote to all men over the age of 21.[220]

- United Kingdom: The Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918 was passed allowing women to stand as members of parliament.[190]

- Czechoslovakia: Czechoslovakia granted women the right to vote.[211]

- 1919

- Germany: Germany granted women the right to vote.[211]

- Azerbaijan: Azerbaijan granted women the right to vote.[221]

- Italy: Women gained more property rights, including control over their own earnings, and access to some legal positions.[222]

- United Kingdom: The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 became law. In a broad opening statement it specified that, "[a] person shall not be disqualified by sex or marriage from the exercise of any public function, or from being appointed to or holding any civil or judicial office or post, or from entering or assuming or carrying on any civil profession or vocation". The Act did provide employment opportunities for individual women and many were appointed as magistrates, but in practice it fell far short of the expectations of the women's movement. Senior positions in the civil service were still closed to women and they could be excluded from juries if evidence was likely to be too "sensitive".[223]

- Luxembourg: Luxembourg granted women the right to vote.[224]

- Canada: Women were granted the right to be candidates in federal elections.[225]

- Netherlands: The Netherlands granted women the right to vote. The right to stand in election was granted in 1917.[226]

- New Zealand: New Zealand allowed women to stand for election into parliament.[227]

- United Kingdom: Nancy Astor became the first woman to take her seat in the House of Commons.[190]

- 1920

- China: The first female students were accepted in Peking University, soon followed by universities all over China.[228]

- Haiti: The apothecary profession was opened to women.[138]

- Korea: The profession of telephone operator, as well as several other professions, such as store clerks, were opened to women.[194]

- Sweden: Legal majority was granted to married women and equal marriage rights were granted to women.[129]

- US: The 19th Amendment was signed into law, granting all American women the right to vote.[121]

- United Kingdom: Oxford University opened its degrees to women.[193]

- 1921

- United Kingdom: The Six Point Group was founded by Lady Rhondda to push for women's social, political, occupational, moral, economic, and legal equality.[193]

- 1922

- China: International Women's Day was celebrated in China from 1922 on.[229]

- United Kingdom: The Law of Property Act 1922 was passed, giving wives the right to inherit property equally with their husbands.[193]

- England: The Infanticide Act was passed, ending the death penalty for women who killed their children if the women's minds were found to be unbalanced.[193]

- 1923

- Nicaragua: Elba Ochomogo became the first woman to obtain a university degree in Nicaragua.[230]

- United Kingdom: The Matrimonial Causes Act gave women the right to petition for divorce on the grounds of adultery.[231]

- 1925

- United Kingdom: The Guardianship of Infants Act gave parents equal claims over their children.[193]

- 1928

- United Kingdom: The right to vote was granted to all UK women equally with men in 1928.[232]

- 1934

- Turkey: Women gained the right to vote and to become a nominee to be elected equally in 1934 after reformations for a new civil law.[citation needed]

Criticism