Forage War

| Forage War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

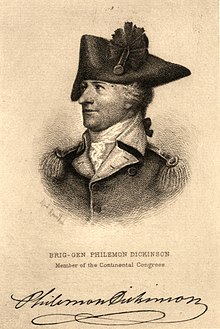

New Jersey militia commander Philemon Dickinson | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

George Washington William Maxwell Philemon Dickinson and others... |

Charles Mawhood Johann Ewald and others... | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Thousands of militia, several companies of regulars | 10,000 (New Jersey garrison size)[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | at least 954 killed, wounded or captured[2] | ||||||

The Forage War was a partisan campaign consisting of numerous small skirmishes that took place in New Jersey during the American Revolutionary War between January and March 1777, following the battles of Trenton and Princeton. After both British and Continental Army troops entered their winter quarters in early January, Continental Army regulars and militia companies from New Jersey and Pennsylvania engaged in numerous scouting and harassing operations against the British and German troops quartered in New Jersey.

The British troops wanted to have fresh provisions to consume, and also required fresh forage for their draft animals and horses. General George Washington ordered the systematic removal of such supplies from areas easily accessible to the British, and companies of American militia and troops harassed British and German forays to acquire such provisions. While many of these operations were small, in some cases they became quite elaborate, involving more than 1,000 troops. The American operations were so successful that British casualties in New Jersey (including those of the battles at Trenton and Princeton) exceeded those of the entire campaign for New York.

Background

In August 1776 the British army began a campaign to gain control over New York City, which was defended by George Washington's Continental Army. Over the next two months, General William Howe quickly gained control of New York, pushing Washington into New Jersey.[3] He then chased Washington south toward Philadelphia. Washington retreated across the Delaware River into Pennsylvania, taking with him all the boats for miles in each direction.[4] Howe then ordered his army into winter quarters, establishing a chain of outposts across New Jersey, from the Hudson River through New Brunswick to Trenton and Bordentown on the Delaware River. The occupation of New Jersey by British and German troops caused friction with the local communities and led to a rise in Patriot militia enlistments. As early as mid-December, these militia companies were harassing British patrols, leading to incidents like Geary's ambush, in which a dragoon leader was killed, and increasing the level of tension in the British and German quarters.[5]

On the night of December 25–26, 1776, Washington crossed the Delaware and surprised the Trenton outpost the following morning, December 26. Over the next two weeks, he went on to win two further battles at Assunpink Creek and Battle of Princeton, leading the British to retreat to northern New Jersey.[6] This period, from December 25, 1776, through January 3, 1777, has become known as the Ten Crucial Days.[7]

Disposition of the armies

General Washington established his headquarters at Morristown, separated from the coast by the Watchung Mountains, a series of low ridges. He established forward outposts to the east and south of these ridges that served not only as a defensive bulwark against potential British incursions across the hills, but also as launch points for raids.[8] Over the course of January and February, Washington's Continental Army shrank to about 2,500 regulars after Washington's incentives for many men to overstay their enlistment periods ran out. A large number of militia from New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania bolstered these forces, and played a significant role that winter.[9]

The British army was initially deployed from posts as far north as Hackensack to New Brunswick. The garrison, numbering about 10,000, was concentrated between New Brunswick and Amboy, with a sizable contingent farther north, from Elizabethtown to Paulus Hook. Militia pressure in January led General Cornwallis to withdraw most of the northern troops to the shores of the Hudson. The resulting concentration of troops overflowed the available housing, which had been entirely abandoned by its residents, with some of the troops even living aboard ships anchored nearby;[10] the cramped quarters led to an increase in camp-related illnesses throughout the winter, and morale was low.[11] The area had been heavily plundered during the American retreat in the fall, so there was little in the way of local provisions.[12] The men subsisted largely on rations such as salt pork, but their draft animals required fresh fodder, for which they sent out raiding expeditions.[13]

Tactics

Early in the winter, Washington sent out detachments of troops to systematically remove any remaining provisions and livestock from convenient access by the British.[14] General Cornwallis sent out small foraging and raiding parties in January. These were met by larger formations (numbering 300 and up) of American militia companies, sometimes with Continental Army support, that led on occasion to significant casualties.[13] In one early example, Brigadier General Philemon Dickinson mustered 450 militia and drove off a British foraging expedition in the Battle of Millstone on January 20.[15] Washington gave his commanders wide latitude in how to act, issuing commands that they were to be "constantly harassing the enemy", and that they should be aggressive in their tactics.[16] These early successes depended in part on successful intelligence; one British commander reported being met with force "notwithstanding the Orders were given, but a few hours before the Troops moved."[17] Even supply convoys bringing provisions from outside the state to the large garrison at New Brunswick were not immune to the American attacks, where the Raritan River and the roads from Perth Amboy offered opportunities for sniping and raiding.[18] Their difficulties led British commanders to change tactics, attempting to lure these militia units into traps involving larger numbers of British regulars.[19]

But even this was not entirely successful, as wily militia and Continental commanders including Continental Army General William Maxwell used superior knowledge of the geography to set even more elaborate traps. In one encounter in late February, British Colonel Charles Mawhood, thinking he had flanked a party of New Jersey militia, suddenly found his advance force flanked by another, larger force. As they were driven back toward Amboy, more and more Americans appeared, ultimately inflicting about 100 casualties. The elite grenadiers of the 42nd Foot, part of Mawhood's vanguard, were badly mauled in the encounter.[20] A British force of 2,000 was repulsed by Maxwell in another well-organized attack a few weeks later.[21]

The ongoing tensions took their toll on the beleaguered British. Johann Ewald, captain of a company of German jägers (essentially light infantry) who were often on the front lines, observed that "the men have to stay dressed day and night ... the horses constantly saddled", and that "the army would have been gradually destroyed through this foraging".[22] Some forage was provided from New York, but it was never sufficient for the army's needs.[22] As a consequence, the British were forced to provide many supplies from Europe, at great cost and risk to the Royal Navy.[23]

Selected Actions

Elizabethtown

A regiment of Waldeck infantry, a few companies of the 71st Foot and a troop of British light dragoons were stationed at Elizabethtown, New Jersey in the winter of 1776–1777. On 5 January 1777, a British cavalry patrol was ambushed by militia near the town. One trooper was killed and a second was wounded. The next day, about 50 Waldeck infantry emerged from the town with a small escort of light dragoons with instructions to clear the country. Led by Captain Georg von Haacke, the strong patrol was attacked near Springfield by New Jersey militia. In Elizabethtown, the soldiers heard distant gunfire. Hours later the bedraggled British horsemen came back without the foot soldiers. Eight or 10 of the Waldeckers were shot down and the entire party captured by the militia. Ordered to pull back to Amboy, the garrison hurriedly left on 7 January. As the troops evacuated Elizabethtown, the militia attacked the rear guard. In the confused retreat, the Americans captured 100 soldiers, the baggage trains of two regiments, and food supplies.[24]

Chatham, Connecticut Farms and Bonhamtown

On 10 January 1777, Colonel Charles Scott's Virginia Continentals captured 70 Highlanders together with their wagons at Chatham.[25] Scott's brigade was composed of the 4th, 5th and 6th Virginia Regiments.[26] At Connecticut Farms on 15 January, 300 New Jersey militia commanded by Colonel Oliver Spencer attacked 100 German foragers. The Americans killed one enemy soldier and captured 70 more. The following day, 350 Americans set upon a large body of British foragers at Bonhamton, killing 21 enemy soldiers and wounding 30 or 40 more. American casualties are not given in any of these actions.[25]

Millstone and Woodbridge

At the Battle of Millstone, Brigadier-General Philemon Dickinson of the New Jersey militia scored a brilliant success. On 20 January 1777 near Van Nest's Mill, 400 militia and 50 Pennsylvania riflemen crossed an icy stream and fought a pitched battle with 500 British regulars and three cannons. The British suffered 25 killed or wounded and 12 captured, losing 43 wagons, 104 horses, 115 heads of cattle and approximately 60 sheep. The Americans admitted losses of four or five men. Afterward, the British were surprised that their opponents on the field consisted of militiamen. On 23 January two British regiments were waylaid by 200 Jersey Blues led by Brigadier-General William Maxwell near Woodbridge. The American inflicted losses of seven killed and 12 wounded while only suffering two men wounded.[27]

Drake's Farm

On 1 February 1777, Brigadier-General Sir William Erskine, 1st Baronet set up a clever trap. He sent a party of foragers to Drake's Farm near Metuchen. When Scott's 5th Virginia tried to attack the small party, Erskine rushed his large force into action. Battalions of grenadiers, light infantry, line infantry of 42nd Regiment of Foot and Hessians appeared, supported by eight artillery pieces. Instead of fleeing, the Virginians launched a vicious attack which momentarily broke a grenadier battalion. Under intense cannon fire, the American attack was stopped, but the Virginians fought tenaciously until the British fell back toward Brunswick. The Americans admitted 30 to 40 casualties while claiming to have killed 36 soldiers and wounding 100 more.[28] The action was marred by an ugly incident when Lieutenant William Kelly and six other wounded Americans were abandoned during a tactical withdrawal. A number of officers from Erskine's force discovered the seven men and killed them with bayonets and musket butts. When the Americans recovered the mangled bodies they were infuriated; Brigadier-General Adam Stephen exchanged a series of irate letters with Erskine, who denied all responsibility for the incident.[29]

Quibbletown

On February 8, 1777, General Cornwallis, with six British generals commanding a force of twelve battalions, about 2,000 troops, planned to attack the American militia, led by Colonel Charles Scott and the 5th Virginia Regiment, and Continentals led by Brigadier General Nathaniel Warner at Quibbletown, New Jersey, now New Market.[30][31] However, the Americans refused to directly engage this foraging party, but attacked the flanks and rear as the British retreated to New Brunswick. Historian Fischer writes: "The British commanders were outgeneraled in the field."[32][33] Hessian Captain Johann von Ewald described the events in his diary and notes that "Since the army would have been gradually destroyed through this foraging, from here on the forage was procured from New York".[34] Other skirmishes occurred in this area on February 20, March 8, and April 4.[35]

Spanktown

On 23 February 1777, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Mawhood was sent with a reinforced brigade to destroy any rebel forces he could catch. He set out with a battalion each of light infantry and grenadiers, plus the 3rd Brigade.[36] The latter formation consisted of the 10th Foot, 37th Foot, 38th Foot and 52nd Foot,[37] recently transferred from the Rhode Island garrison.[38] Near Spanktown (now Rahway), Mawhood found a group of militia herding some livestock covered by a larger body of Americans waiting on a nearby hill. The British officer sent the grenadier company of the 42nd Foot on a wide flanking maneuver. Just as the grenadiers prepared to launch their assault, they were fired on from ambush and routed with the loss of 26 men. At this moment, Maxwell sent his superior force forward to envelop Mawhood's force. The American force included the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th New Jersey Regiments, the 1st and 8th Pennsylvania Regiments, and the German Battalion. Mawhood's surprised men were hounded all the way back to Amboy, which they reached at 8:00 PM. The Americans lost 5 killed and 9 wounded, and claimed to have inflicted 100 casualties. Mawhood admitted losing 69 killed and wounded and 6 missing.[39]

Casualty estimates

Historian David Hackett Fischer compiled a list that he describes as "incomplete", consisting of 58 actions that occurred between January 4 and March 21, 1777.[40] The documented British and German casualties numbered more than 900; a number of the events do not include any casualty reports. Combined with their losses at Trenton and Princeton, the British lost more men in New Jersey than they did during the campaign for New York City. Fischer does not estimate American casualties, and other historians (e.g. Ketchum and Mitnick) have not compiled any casualty estimates.[41] Fischer notes that relatively few official reports of American (either militia or Continental Army) unit strengths for this time period have survived.[42]

Ending

The 1777 military campaigns began to take shape in April. General Charles Cornwallis punctuated the winter skirmishes with an attack on the Continental Army outpost at Bound Brook on April 13. In the Battle of Bound Brook, he very nearly captured its commander, Benjamin Lincoln.[43] Outnumbering the Americans 2,000 to 500, the British scattered the militia but met stubborn resistance from the 8th Pennsylvania Regiment. The British captured three 3-pound guns and 20 or 30 men and killed six Americans, but the bulk of Lincoln's force got away.[44] General Washington moved his army from its winter quarters at Morristown to a more forward position at Middlebrook in late May to better react to British moves.[45] As General Howe prepared his Philadelphia campaign, he first moved a large portion of his army to Somerset Court House in mid-June, apparently in an attempt to draw Washington from the Middlebrook position.[46] When this failed, Howe withdrew his army back to Perth Amboy, and embarked it on ships bound for the Chesapeake Bay.[47] Northern and coastal New Jersey continued to be the site of skirmishing and raiding by the British forces that occupied New York City for the rest of the war.[48]

See also

- American Revolutionary War §British New York counter-offensive. The 'Forage War' placed in overall sequence and strategic context.

- The Battle of Drake's Farm.

Notes

- ^ Ketchum, p. 382

- ^ Fischer, p. 418

- ^ Ketchum, pp. 101–159

- ^ Ketchum, pp. 160–241

- ^ Fischer, pp. 184–199

- ^ Ketchum, pp. 293–379

- ^ "Ten Crucial Days". Crossroads of the American Revolution Association.

- ^ Fischer, p. 354

- ^ Fischer, pp. 348–349

- ^ Fischer, pp. 349–350

- ^ Fischer, p. 351

- ^ Fischer, p. 350

- ^ a b Fischer, p. 352

- ^ Lundin, p. 223

- ^ Fischer, p. 355

- ^ Fischer, p. 353

- ^ Lundin, p. 224

- ^ Lundin, p. 225

- ^ Fischer, p. 356

- ^ Fischer, pp. 356–357

- ^ Fischer, p. 357

- ^ a b Fischer, p. 358

- ^ Mitnick, p. 52

- ^ Fischer (2004), p. 347, pp. 415-416. Fischer's dates in his narrative and his appendix differ by one day. The dates in the appendix were used for the two clashes.

- ^ a b Fischer (2004), p. 352, p. 416

- ^ Fischer (2004), p. 409

- ^ Fischer (2004), p. 355, p. 416

- ^ Fischer (2004), p. 356, p. 416

- ^ Fischer (2004), pp. 377-378

- ^ "Piscataway History". Piscataway Public Library. Archived from the original on 2018-01-24. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ^ Dickinson, Philemon (February 9, 1777). "To George Washington from Brigadier General Philemon Dickinson, 9 February 1777". Founders Online, National Archives.

about 2,000 Men

- ^ Fischer (2004), p. 356.

- ^ Fischer (2004), p. 417.

- ^ Ewald (1979), pp. 53–55.

- ^ Revolutionary War Skirmishes in the Area, 1777. Piscataway, New Jersey.

- ^ Fischer (2004), p. 356

- ^ Fischer (2004), p. 395. The assumption is that the 3rd Brigade organization had not changed since 25 December 1776.

- ^ Fischer (2004), p. 350

- ^ Fischer (2004), pp. 356-357, p. 417. The author includes "Stricker's Maryland regiment". Since its commander Nicholas Haussegger deserted and George Stricker was second in command, this unit must be the German Battalion of Marylanders and Pennsylvanians.

- ^ Fischer, pp. 415–418

- ^ Fischer, p. 359

- ^ Fischer, p. 382

- ^ Lundin, p. 255

- ^ Boatner (1994), p. 100-101

- ^ Lundin, p. 313

- ^ Lundin, p. 317

- ^ Lundin, pp. 325–326

- ^ See e.g. Karels or Mitnick for further details on the role of northern New Jersey in the war.

References

- Boatner, Mark M. III (1994). Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0578-3.

- Ewald, Johann (1979). Tustin, Joseph P. (ed.). Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal. Translated by Tustin, Joseph P. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02153-0.

- Fischer, David Hackett (2004). Washington's Crossing. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518159-3.

- Karels, Carol (2007). The Revolutionary War in Bergen County: The Times That Tried Men's Souls. Charleston, SC: History Press. ISBN 978-1-59629-358-8.

- Ketchum, Richard (1999). The Winter Soldiers: The Battles for Trenton and Princeton. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-6098-0.

- Lundin, Leonard (1972) [1940]. Cockpit of the Revolution: the war for independence in New Jersey. New York: Octagon Books. ISBN 978-0-374-95143-6.

- Mitnick, Barbara (2005). New Jersey in the American Revolution (1st ed.). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3602-6.