Frederick William I of Prussia

| Frederick William I | |

|---|---|

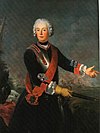

Portrait by Antoine Pesne, c. 1733 | |

| King in Prussia Elector of Brandenburg | |

| Reign | 25 February 1713 – 31 May 1740 |

| Predecessor | Frederick I |

| Successor | Frederick II |

| Born | 14 August 1688 Berlin, Brandenburg-Prussia |

| Died | 31 May 1740 (aged 51) Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | |

| Issue |

|

| House | Hohenzollern |

| Father | Frederick I |

| Mother | Sophia Charlotte of Hanover |

| Religion | Calvinist |

| Signature |  |

Frederick William I (Template:Lang-de; 14 August 1688 – 31 May 1740), known as the "Soldier King" (Template:Lang-de[1]), was King in Prussia and Elector of Brandenburg from 1713 until his death in 1740, as well as Prince of Neuchâtel. He was succeeded by his son, Frederick the Great.

Early years

He was born in Berlin to King Frederick I of Prussia and Princess Sophia Charlotte of Hanover. During his first years, he was raised by the Huguenot governess Marthe de Roucoulle.[2] When Great Northern War plague outbreak devastated Prussia, the inefficiency and corruption of the king's favorite ministers and senior officials were highlighted. Frederick William with a party that formed at the court brought down the leading minister Johann Kasimir Kolbe von Wartenberg and his cronies following an official investigation that exposed Wartenberg's huge-scale misappropriation and embezzlement. His close associate August David zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Hohenstein was imprisoned at Spandau Citadel, fined 70,000 thalers and banished subsequently. The incident exerted great influence on Frederick William, making him resent corruption, wastage and inefficiency and realize the necessity of institutional reform. It also became the first time he actively participated in politics. From then on, Frederick I began to let his son take more power.[3]

Reign

His father had successfully acquired the title of king for the margraves of Brandenburg. On ascending the throne in 1713, Frederick William I did much to improve Prussia economically and militarily. He replaced mandatory military service among the middle class with an annual tax, and he established schools and hospitals. The king encouraged farming, reclaimed marshes, stored grain in good times and sold it in bad times. He dictated the manual of Regulations for State Officials, containing 35 chapters and 297 paragraphs in which every public servant in Prussia could find his duties precisely set out: a minister or councillor failing to attend a committee meeting, for example, would lose six months' pay; if he absented himself a second time, he would be discharged from the royal service. In short, Frederick William I concerned himself with every aspect of his relatively small country, ruling an absolute monarchy with great energy and skill.

The king also took an interest in Prussian colonial affairs. In 1717, he revoked the charter of the Brandenburg Africa Company (BAC), which had been granted said charter by his father to establish a colony in West Africa known as the Brandenburg Gold Coast (and used it to transport between 17,000 and 30,000 enslaved Africans to the Americas). The king was unwilling to spend money on maintaining either the colony or the Prussian Navy, preferring to utilise state revenues on enlarging the Royal Prussian Army. In 1721, Frederick William sold the Brandenburg Gold Coast to the Dutch West India Company in exchange for 7,200 ducats and 12 enslaved African boys wearing gold chains.[4][5]

In 1732, the king invited the Salzburg Protestants to settle in East Prussia, which had been depopulated by plague in 1709. Under the terms of the Peace of Augsburg, the prince-archbishop of Salzburg could require his subjects to practice the Catholic faith, but Protestants had the right to emigrate to a Protestant state. Prussian commissioners accompanied 20,000 Protestants to their new homes on the other side of Germany. Frederick William I personally welcomed the first group of migrants and sang Protestant hymns with them.[6]

Frederick William intervened briefly in the Great Northern War, allied with Peter the Great of Russia, in order to gain a small portion of Swedish Pomerania; this gave Prussia new ports on the Baltic Sea coast. More significantly, aided by his close friend Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Dessau, the "Soldier-King" made considerable reforms to the Prussian army's training, tactics and conscription program—introducing the canton system, and greatly increasing the Prussian infantry's rate of fire through the introduction of the iron ramrod. Frederick William's reforms left his son Frederick with the most formidable army in Europe, which Frederick used to increase Prussia's power. The observation that "the pen is mightier than the sword" has sometimes been attributed to him. (See as well: "Prussian virtues".)

Although a highly effective ruler, Frederick William had a perpetually short temper which sometimes drove him to physically attack servants (or even his own children) with a cane at the slightest perceived provocation. His violent, harsh nature was further exacerbated by his inherited porphyritic disease, which gave him gout, obesity and frequent crippling stomach pains.[7] He also had a notable contempt for France, and would sometimes fly into a rage at the mere mention of that country, although this did not stop him from encouraging the immigration of French Huguenot refugees to Prussia.

Burial and reburials

Frederick William died in 1740 at age 51 and was interred at the Garrison Church in Potsdam. During World War II, in order to protect it from advancing allied forces, Hitler ordered the king's coffin, as well as those of Frederick the Great and Paul von Hindenburg, into hiding, first to Berlin and later to a salt mine outside of Bernterode. The coffins were later discovered by occupying American forces, who re-interred the bodies in St. Elisabeth's Church in Marburg in 1946. In 1953 the coffin was moved to Burg Hohenzollern, where it remained until 1991, when it was finally laid to rest on the steps of the altar in the Kaiser Friedrich Mausoleum in the Church of Peace on the palace grounds of Sanssouci. The original black marble sarcophagus collapsed at Burg Hohenzollern—the current one is a copper copy.[8]

Relationship with Frederick II

His eldest surviving son was Frederick II (Fritz), born in 1712. Frederick William wanted him to become a fine soldier. As a small child, Fritz was awakened each morning by the firing of a cannon. At the age of 6, he was given his own regiment of children [9] to drill as cadets, and a year later, he was given a miniature arsenal.

The love and affection Frederick William had for his heir initially was soon destroyed due to their increasingly different personalities. Frederick William ordered Fritz to undergo a minimal education, live a simple Protestant lifestyle, and focus on the Army and statesmanship as he had. However, the intellectual Fritz was more interested in music, books and French culture, which were forbidden by his father as decadent and unmanly. As Fritz's defiance for his father's rules increased, Frederick William would frequently beat or humiliate Fritz (he preferred his younger sibling Augustus William). Fritz was beaten for being thrown off a bolting horse and wearing gloves in cold weather. After the prince attempted to flee to England with his tutor, Hans Hermann von Katte, the enraged King had Katte beheaded before the eyes of the prince, who himself was court-martialled.[10] The court declared itself not competent in this case. Whether it was the king's intention to have his son executed as well (as Voltaire claims) is not clear. However, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI intervened, claiming that a prince could only be tried by the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire itself. Frederick was imprisoned in the Fortress of Küstrin from 2 September to 19 November 1731 and exiled from court until February 1732, during which time he was rigorously schooled in matters of state. After achieving a measure of reconciliation, Frederick William had his son married to Princess Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern, whom Frederick despised, but then grudgingly allowed him to indulge in his musical and literary interests again. He also gifted him a stud farm in East Prussia, and Rheinsberg Palace. By the time of Frederick William's death in 1740, he and Frederick were on at least reasonable terms with each other.

Although the relationship between Frederick William and Frederick was clearly hostile, Frederick himself later wrote that his father "penetrated and understood great objectives, and knew the best interests of his country better than any minister or general."

Marriage and family

Frederick William married his first cousin Sophia Dorothea of Hanover, George II's younger sister (daughter of his uncle, King George I of Great Britain and Sophia Dorothea of Celle) on 28 November 1706. Frederick William was faithful and loving to his wife[11] but they did not have a happy relationship: Sophia Dorothea feared his unpredictable temper and resented him, both for allowing her no influence or independence at court, and for refusing to marry her children to their English cousins. She also abhorred his cruelty towards their son and heir Frederick (with whom she was close), although rather than trying to mend the relationship between father and son she frequently spurred Frederick on in his defiance. They had fourteen children, including:

| Name | Portrait | Lifespan | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frederick Louis Prince of Prussia |

|

23 November 1707- 13 May 1708 |

Died in infancy |

| Friedrike Wilhelmine Margravine of Brandenburg-Bayreuth |

|

3 July 1709- 14 October 1758 |

Married Frederick, Margrave of Brandenburg-Bayreuth and had issue |

| Frederick William Prince of Prussia |

|

16 August 1710- 21 July 1711 |

Died in infancy |

| Frederick II the Great King of Prussia |

|

24 January 1712- 17 August 1786 |

King in Prussia (1740–1772); King of Prussia (1772–1786); married Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern but had no issue |

| Charlotte Albertine Princess of Prussia |

|

5 May 1713- 10 June 1714 |

Died in infancy |

| Frederica Louise Margravine of Brandenburg-Ansbach |

|

28 September 1714- 4 February 1784 |

Married Charles William Frederick, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach and had issue |

| Philippine Charlotte Duchess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel |

|

13 March 1716- 17 February 1801 |

Married Charles I, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and had issue |

| Louis Charles William Prince of Prussia |

|

2 May 1717- 31 August 1719 |

Died in early childhood |

| Sophia Dorothea Margravine of Brandenburg-Schwedt Princess in Prussia |

|

25 January 1719- 13 November 1765 |

Married Frederick William, Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt, Prince in Prussia and had issue |

| Louisa Ulrika Queen of Sweden |

|

24 July 1720- 2 July 1782 |

Married Adolf Frederick, King of Sweden and had issue |

| Augustus William Prince of Prussia |

|

9 August 1722- 12 June 1758 |

Married Duchess Luise of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and had issue (including Frederick William II) |

| Anna Amalia |

|

9 November 1723- 30 March 1787 |

Became Abbess of Quedlinburg 16 July 1755 |

| Frederick Henry Louis Prince of Prussia |

|

18 January 1726- 3 August 1802 |

Married Princess Wilhelmina of Hesse-Kassel but had no issue |

| Augustus Ferdinand Prince of Prussia |

|

23 May 1730- 2 May 1813 |

Married Margravine Elisabeth Louise of Brandenburg-Schwedt and had issue |

He was the godfather of the Prussian envoy Friedrich Wilhelm von Thulemeyer and of his grand-nephew, Prince Edward Augustus of Great Britain.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Frederick William I of Prussia[12] |

|---|

See also

References

- ^ Taylor, Ronald (1997). Berlin and Its Culture: A Historical Portrait. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. p. 51.

- ^ Thomas Carlyle: History of Friedrich II of Prussia: Called Frederick the Great, 1870

- ^ Clark, Christopher (2006). Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947. United Kingdom: Penguin Books. p. 87.

- ^ Felix Brahm; Eve Rosenhaft (2016). Slavery Hinterland: Transatlantic Slavery and Continental Europe, 1680-1850. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 26–30. ISBN 978-1-78327-112-2.

- ^ Sebastian Conrad: Deutsche Kolonialgeschichte. C.H. Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-56248-8, p.18.

- ^ Walker, Mack (1992). The Salzburg Transaction: Expulsion and Redemption in Eighteenth-Century Germany. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-2777-0.

- ^ [Mitford, Nancy "Frederick the Great" (1970) P6]

- ^ MacDonogh, Giles (2007). After the Reich: The Brutal History of the Allied Occupation. New York: Basic Books. p. 93.

- ^ Mitford, Nancy (1970). "Frederick the Great" pp.11

- ^ Farquhar, Michael (2001). A Treasure of Royal Scandals. New York: Penguin Books. p. 114. ISBN 0-7394-2025-9.

- ^ Mitford, Nancy (1970). "Frederick the Great" p.5

- ^ Genealogie ascendante jusqu'au quatrieme degre inclusivement de tous les Rois et Princes de maisons souveraines de l'Europe actuellement vivans [Genealogy up to the fourth degree inclusive of all the Kings and Princes of sovereign houses of Europe currently living] (in French). Bourdeaux: Frederic Guillaume Birnstiel. 1768. p. 16.

Further reading

- Dorwart, Reinhold A. The administrative reforms of Frederick William I of Prussia (Harvard University Press, 2013).

- Fann, Willerd R. "Peacetime Attrition in the Army of Frederick William I, 1713–1740." Central European History 11.4 (1978): 323–334. online

- Gothelf, Rodney. "Frederick William I and the beginnings of Prussian absolutism, 1713–1740." in The Rise of Prussia 1700–1830 (Routledge, 2014) pp. 47–67.

- Hashagen, Justus (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). pp. 63–64.