Genocide of indigenous peoples in Brazil

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide of indigenous peoples |

|---|

| Issues |

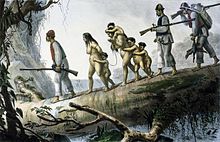

The genocide of indigenous peoples in Brazil began with the Portuguese colonization of the Americas, when Pedro Álvares Cabral made landfall in what is now the country of Brazil in 1500.[1] This started the process that led to the depopulation of the indigenous peoples in Brazil, because of disease and violent treatment by Portuguese settlers, and their gradual replacement with colonists from Europe and enslaved peoples from Africa. This process has been described as a genocide, and continues into the modern era with the ongoing destruction of indigenous peoples of the Amazonian region.[2][3]

Over eighty indigenous tribes were destroyed between 1900 and 1957, and the overall indigenous population declined by over eighty percent, from over one million to around two hundred thousand.[4] The 1988 Brazilian Constitution recognises indigenous peoples' right to pursue their traditional ways of life and to the permanent and exclusive possession of their "traditional lands", which are demarcated as Indigenous Territories.[5] In practice, however, Brazil's indigenous people still face a number of external threats and challenges to their continued existence and cultural heritage.[6] The process of demarcation is slow—often involving protracted legal battles—and FUNAI do not have sufficient resources to enforce the legal protection on indigenous land.[7][8][6]

Since the 1980s there has been an increase in the exploitation of the Amazon Rainforest for mining, logging and cattle ranching, posing a severe threat to the region's indigenous population. Settlers illegally encroaching on indigenous land continue to destroy the environment necessary for indigenous peoples' traditional ways of life, provoke violent confrontations and spread disease.[6] Peoples such as the Akuntsu and Kanoê have been brought to the brink of extinction within the last three decades.[9][10] On 13 November 2012, the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) submitted to the United Nations a human rights document with complaints about new proposed laws in Brazil that would further undermine their rights if approved.[11]

Several non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have been formed due to the ongoing persecution of the indigenous peoples in Brazil, and international pressure has been brought to bear on the state after the release of the Figueiredo Report which documented massive human rights violations.[12]

The abuses have been described as genocide, ethnocide and cultural genocide.[13]

Affected tribes

In the 1940s, the state and the Indian Protection Service (Serviço de Proteção aos Índios, SPI) forcibly relocated the Aikanã, Kanôc, Kwazá and Salamái tribes to work on rubber plantations. During the journey many of the indigenous peoples starved to death; those who survived the journey were placed in an IPS settlement called Posto Ricardo Franco. These actions resulted in the near extinction of the Kanôc tribe.[14]

The ethnocide of the Yanomami has been well documented; there are an estimated nine thousand currently living in Brazil in the Upper Orinoco drainage and a further fifteen thousand in Venezuela.[15] The NGO Survival International has reported that throughout the 1980s up to 6000 thousand gold prospectors entered Yanomami territory bringing diseases the Yanomami had no immunity to, the prospectors shot them and destroyed entire villages, and Survival International estimates that up to twenty per cent of the people were dead within seven years.[16]

The Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, whose territory has been protected by law since 1991, saw an influx of an estimated 800 people in 2007. The tribal leaders met with the civil authorities and demanded the trespassers be evicted. This tribe, initially contacted in 1981, saw a severe decline in population after disease was introduced by settlers and miners. Their numbers are now estimated at a few hundred.[17]

In 2022, the Man of the Hole, who was totally isolated for 26 years and was his uncontacted tribe's last survivor of genocide, died. He lived in Tanaru Indigenous Territory in Rondônia state. The Observatory for the Human Rights of Uncontacted and recently contacted Peoples called for the territory to be permanently protected as a memorial to Indigenous Genocide.[18]

Portuguese colonization

During the Portuguese colonization of the Americas, Cabral made landfall off the Atlantic coast. Over the following decade the indigenous Tupí, Tapuya, Caeté, Goitacá and other tribes which lived along the coast suffered large depopulation due to disease and violence. A process of miscegenation between Portuguese settlers and indigenous women also occurred.[19] It is estimated that of the 2.5 million indigenous peoples who had lived in the region which now comprises Brazil, less than 10 percent survived to the 1600s.[2] The primary reason for depopulation was diseases such as smallpox that advanced far beyond movement of European settlers,[20] anthropologist and historian Darcy Ribeiro highlights how the majority of these deaths occurred initially due to European diseases spreading from the Portuguese colonisers to indigenous peoples, but that this was just a precursor to later, more horrendous, ethnocide and genocide.[21]

20th and 21st century

Anti-indigenous sentiment and violence has persisted into the 21st century.[2][3] From 2007 to 2017, 833 indigenous people were murdered according to the Special Secretariat for Indigenous Health.[22]

Genocide scholars have identified actions by Brazil in the 20th century as actions of genocide.[23][24]

The deforestation of the Amazon rainforest has been highlighted as a driving factor in the destruction of indigenous peoples in Brazil and the wider Amazon region.[25][6]

Genocide scholar Adam Jones and historian Wendy Lower point to the killing of men and the sexual abuse and enslavement of women from indigenous groups is not just genocide but serves as an example of gendercide perpetrated by the Brazilian state.[26]

State reaction

In 1952, Brazil ratified the genocide convention and incorporated into their penal laws article II of the convention.[27] While the statute was being drafted, Brazil argued against the inclusion of cultural genocide, claiming that some minority groups may use it to oppose the "normal assimilation" which occurs in a new country.[28] According to professor of law at Vanderbilt University Larry May, the argument put forward by Brazil was significant, but cultural genocide should not be cast aside, and this type of genocide should be included within the definition of genocide.[29]

In 1967, public prosecutor, Jader de Figueiredo Correia, submitted the Figueiredo Report to the dictatorship which was then ruling the country. The report, which ran to seven thousand pages, remained hidden for over forty years. Its release caused an international furor. The rediscovered documents were examined by the National Truth Commission, which was tasked with the investigations of human rights violations which occurred in the periods 1947 through to 1988. The report reveals that the SPI had enslaved indigenous people, tortured children and stolen land. The Truth Commission was of the opinion that entire tribes in Maranhão were completely eradicated and in Mato Grosso, an attack on thirty Cinturão Largo left only two survivors (the "Massacre at 11th Parallel"). The report also states that landowners and members of the SPI had entered isolated villages and deliberately introduced smallpox. Of the one hundred and thirty four people accused in the report the state has as yet not tried a single one.[30] The report also detailed instances of mass killings, rapes, and torture. Figueiredo stated that the actions of the SPI had left the indigenous peoples near extinction. The state abolished the SPI following the release of the report. The Red Cross launched an investigation after further allegations of ethnic cleansing were made after the SPI had been replaced.[31][32]

In 1969, Brazil's permanent representative to the UN argued that Brazil could not be charged with genocide against the indigenous peoples of the Amazon as "since the criminal parties involved never eliminated the Indians as an ethnic or cultural group […] there was lacking the special malice or motivation necessary to characterize the occurrence of genocide.".[33]

In 1992, a group who had been prospecting for gold were tried for the attempted genocide of the Yanomami tribe. A report from an anthropologist, which was submitted as evidence during the trial, stated that the prospectors' entry into Yanomami territory had an adverse effect on their lives, as the prospectors carried diseases. They had also contaminated the rivers which the Yanomami used as a source of food.[27] The UN reported that thousands of the Yanomami have been killed as the Brazilian government failed to enforce the law and that, even after the Yanomami peoples' territory had been demarcated, the state had not provided the necessary resources to stop the illegal incursion of gold prospectors. These prospectors have caused massive forest fires which have led to the destruction of extensive areas of both croplands and rainforest.[34]

In 2014, Volume II, Chapter 5 of the official Report of the National Truth Commission acknowledged the deaths of at least 8,000 indigenous people during the period under investigation and made 13 recommendations to redress the situation, beginning with a public apology from the Brazilian State to the indigenous peoples, and including "creation of a specific truth commission for indigenous issues; a commemorative date for the events that occurred; the creation of museums; production of didactic and audiovisual material to be shared in schools, on television, and on the internet; the implementation of actions to preserve the culture of indigenous peoples; delivery of all kinds of documents from the dictatorship to these peoples; and the return of territories taken from them".[35] Few, if any, of these recommendations have been implemented.

From 2019 to 2022, during the four years of former president Jair Bolsonaro's administration, an average of one indigenous person suffered violence every day. With around 373.8 cases of violence against this population per year, the figure represents a significant increase compared to the previous four-year period (54%), under the governments of Michel Temer and Dilma Rousseff, when the average was 242.5 cases per year, according to a report by the Indigenous Missionary Council (Cimi).

International reaction

At the 1992 Earth Summit in Brazil, the Kari-Oka Declaration and the Indigenous Peoples Earth Charter were presented by the representatives of indigenous peoples from around the world. The Kari-Oka Declaration states "We continue to maintain our rights as peoples despite centuries of deprivation, assimilation and genocide". The declaration also asserted that the genocide convention must be amended so as to include the genocide of indigenous peoples.[36] The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) was founded in 1968 in response to the genocide of indigenous peoples in Brazil and Paraguay, and in 1969 Survival International was founded in London as a response to the atrocities, theft of land and genocide occurring in the Brazilian Amazon. In 1972 anthropologists from Harvard University founded Cultural Survival.[37]

The World Bank has been subject to criticism over loans which have been used to help fund the dislocation of indigenous peoples and environmental destruction. The Polonoreste project caused wholesale deforestation, ecological damage on a wide scale, as well as the forced relocation of indigenous communities. The project led to an international campaign that resulted in the World Bank suspending loans.[4]

See also

- List of extinct Indigenous peoples of Brazil

- Yanomami humanitarian crisis – Ongoing humanitarian crisis in the Yanomami territory in Brazil

- Genocide of Indigenous peoples in Paraguay

- Genocide of indigenous peoples in Venezuela

- Taíno genocide

- Putumayo genocide

References

- ^ Naccache 2019, p. 118.

- ^ a b c Churchill 2000, p. 433.

- ^ a b Scherrer 2003, p. 294.

- ^ a b Hinton 2002, p. 57.

- ^ Federal Constitution of Brazil. Chapter VII Article 231.

- ^ a b c d "2008 Human Rights Report: Brazil". United States Department of State: Bureau for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. 25 February 2009. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^

- Borges, Beto; Combrisson, Gilles. "Indigenous Rights in Brazil: Stagnation to Political Impasse". South and Meso American Indian Rights Center. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- Schwartzman, Stephan; Valéria Araújo, Ana; Pankararú, Paulo (1996). "Brazil: The Legal Battle Over Indigenous Land Rights". NACLA Report on the Americas. 29 (5): 36–43. doi:10.1080/10714839.1996.11725759. Archived from the original on 20 April 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- "Brazilian Indians 'win land case'". BBC News. 11 December 2008. Archived from the original on 6 October 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ "Indigenous Lands > Introduction > About Lands". Povos Indígenas no Brasil. Instituo Socioambiental (ISA). Archived from the original on 27 January 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Instituto Socioambiental (ISA). "Introduction > Akuntsu". Povos Indígenas no Brasil. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ Instituto Socioambiental (ISA). "Introduction > Kanoê". Povos Indígenas no Brasil. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ "English version of human rights complaint document submitted to the United Nations by the National Indigenous Peoples Organization from Brazil (APIB)". Earth Peoples. 13 November 2012. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ "'Lost' report exposes Brazilian Indian genocide". Survival International. 25 April 2013. Archived from the original on 14 August 2024. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^

- Barbara 2017

- "Brazil Experts: A 'Genocide Is Underway' Against Uncontacted Tribes". EcoWatch. 8 October 2019. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- "Brazilian president accused of inciting genocide of Indigenous people". CBC News. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- Demetrio & Kozicki 2019, pp. 129–169

- Miotto, Tiago (20 July 2020). "A ameaça de genocídio que paira sobre os povos indígenas isolados no Brasil" [The threat of genocide looming over isolated indigenous peoples in Brazil]. Cimi (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 23 June 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- Nuevatribuna (7 February 2020). "Bolsonaro y su "plan genocida" contra los pueblos originarios" [Bolsonaro and his "genocidal plan" against indigenous peoples]. Nuevatribuna (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 7 December 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- "Amazonie. Au Brésil, un génocide en marche" [Amazonia. In Brazil, a genocide is underway]. Courrier international (in French). 6 November 2019. Archived from the original on 8 August 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ Van Der Voort 2004, p. 5.

- ^ Haviland, Prins & Walrath 2013, p. 628.

- ^ Kopenawa Yanomami 2013.

- ^ "Massive invasion of isolated Indians land". Survival International. 12 January 2007. Archived from the original on 6 July 2024.

- ^ "A symbol of Indigenous genocide: "The Man of the Hole" dies in Brazil". Survival International. 28 August 2022. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024.

- ^ Ribeiro, Darcy (1997). O Povo Brasileiro. 7: 28–33, 72–75 and 95–101.

{cite journal}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Unnatural Histories – Amazon". BBC Four.

- ^ Naccache 2019, p. 119.

- ^ Barbara 2017.

- ^ Kutner, Luis; Katin, Ernest (5 March 2019). "World Genocide Tribunal: A Proposal for Planetary Preventive Measures Supplementing a Genocide Early Warning System". In Charny, Israel W. (ed.). Toward the Understanding and Prevention of Genocide: Proceedings of the International Conference on the Holocaust and Genocide. Routledge. pp. 330–348 [337]. ISBN 978-0-367-21417-3.

- ^ Smith, Roger W. (1999). "State Power and Genocidal Intent: On the Uses of Genocide in the Twentieth Century". In Chorbajian, Levan; Shirinian, George (eds.). Studies in Comparative Genocide. Macmillan Press. pp. 3–14 [3–4]. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-27348-5. ISBN 978-1-349-27348-5.

- ^ Naccache 2019, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Jones, Adam; Lower, Wendy (2023). "Genocide and Gender: Dynamics and Consequences". In Kiernan, Ben; Lemos, T. M.; Taylor, Tristan S. (eds.). The Cambridge World History of Genocide. Vol. I: Genocide in the Ancient, Medieval and Premodern World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 103–126. doi:10.1017/9781108655989. ISBN 978-1-108-49353-6.

- ^ a b Quigley 2006, p. 48.

- ^ Levene, Mark (2005). "Definitional Conundrums". Genocide in the Age of the Nation-State. Vol. I: The Meaning of Genocide. I.B. Tauris. p. 45. ISBN 1-85043-752-1.

- ^ May 2010, p. 103.

- ^ Watts & Rocha 2013.

- ^ Garfield 2001, p. 143.

- ^ Warren 2001, p. 84.

- ^ Kuper, Leo (1984). "Types of Genocide and Mass Murder*". In Charny, Israel W. (ed.). Toward the Understanding and Prevention of Genocide: Proceedings of the International Conference on the Holocaust and Genocide. Routledge. pp. 32–50 [33]. ISBN 978-0-367-21417-3.

..the crime committed against the Brazilian indigenous population cannot be characterized as genocide, since the criminal parties involved never eliminated the Indians as an ethnic or cultural group. Hence, there was lacking the special malice or motivation necessary to characterize the occurrence of genocide. The crimes in question were committed for exclusively economic reasons, the perpetrators having acted solely to take possession of the lands of their victims.

- ^ Travis 2013, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Demetrio & Kozicki 2019, p. 137.

- ^ Totten & Hitchcock 2010, p. 4.

- ^ Morgan 2011, p. 65.

Works cited

- Barbara, Vanessa (29 May 2017). "Opinion | The Genocide of Brazil's Indians". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 21 June 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- Churchill, Ward (2000). Charny, Israel W. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Genocide. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0874369281.

- Demetrio, André; Kozicki, Katya (2019). "A (In)Justiça de Transição para os Povos Indígenas no Brasil" [Transitional (In)Justice for Indigenous Peoples in Brazil]. Revista Direito e Práxis (in Portuguese). 10 (1): 129–169. doi:10.1590/2179-8966/2017/28186. ISSN 2179-8966.

- Garfield, Seth (2001). Indigenous Struggle at the Heart of Brazil: State Policy, Frontier Expansion and the Xavante Indians, 1937–1988. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822326656.

- Haviland, William A.; Prins, Harald E. L.; Walrath, Dana (2013). Anthropology: The Human Challenge. Wadsworth. ISBN 978-1133941323.

- Hinton, Alexander L. (2002). Annihilating Difference: The Anthropology of Genocide. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520230293.

- Kopenawa Yanomami, Davi (2013). "The Yanomami". Survival International. Archived from the original on 1 June 2024.

- May, Larry (2010). Genocide: A Normative Account. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521122962.

- Morgan, Rhiannon (2011). Transforming Law and Institution. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0754674450.

- Naccache, Genna (2019). "Genocide and settler colonialism: How a Lemkinian concept of genocide informs our understanding of the ongoing situation of the Guarani Kaiowá in Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil". In Bachman, Jeffrey S. (ed.). Cultural Genocide: Law, Politics, and Global Manifestations. Routledge. pp. 118–139. ISBN 978-1-351-21410-0.

- Quigley, John B. (2006). The Genocide Convention: An International Law Analysis. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0754647300.

- Scherrer, Christian P. (2003). Ethnicity Nationalism and Violence: Conflict Management, Human Rights and Multilateral Regimes. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0754609568.

- Totten, Samuel; Hitchcock, Robert K. (2010). Genocide of Indigenous Peoples: Genocide: A Critical Bibliographic Review. Transaction. ISBN 978-1412814959.

- Travis, Hannibal (2013). Ethnonationalism, Genocide, and the United Nations. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415531252.

- Van Der Voort, Hein (2004). A Grammar of Kwaza. Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110178692.

- Warren, Jonathan W. (2001). Racial Revolutions: Antiracism and Indian Resurgence in Brazil. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822327417.

- Watts, Jonathan; Rocha, Jan (19 May 2013). "Brazil's 'lost report' into genocide surfaces after 40 years". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 August 2024.