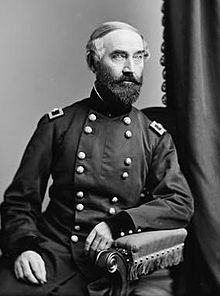

George W. Cullum

George Washington Cullum | |

|---|---|

George Washington Cullum | |

| Born | 25 February 1809 New York City, New York |

| Died | 28 February 1892 (aged 83) New York City, New York |

| Place of burial | Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Service | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1833–1874 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | Corps of Engineers |

| Commands | United States Military Academy |

| Battles / wars | American Civil War |

| Awards | Cullum Geographical Medal (establisher) |

| Other work | Author |

George Washington Cullum (25 February 1809 – 28 February 1892) was an American soldier, engineer and writer. He worked as the supervising engineer on the building and repair of many fortifications across the country. Cullum served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War, primarily in the Western Theater and served as the 16th Superintendent of the United States Military Academy. Following his retirement from the Army, he became a prominent figure in New York society, serving in many societies, and as vice president of the American Geographical Society. The society named the Cullum Geographical Medal after him.

Birth and early years

Cullum was born in New York City on 25 February 1809, to Arthur and Harriet Sturges Cullum. He was raised in Meadville, Pennsylvania. His father worked as a lawyer and an agent of a land company.[1][2] Cullum attended the United States Military Academy, from 1 July 1829 to 1 July 1833, when he graduated third in the Class of 1833.[3] He designed the Independent Congregational Church at Meadville and it was built in 1835–1836. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[4]

Pre-Civil War service

Cullum was appointed to the United States Army Corps of Engineers as a brevet second lieutenant on 1 July 1833. He served as the assistant engineer for Fort Adams in 1833. The following year Cullum served as the assistant to the chief engineer at Washington D. C., where he remained for two years. He was then involved in inspections of Forts Severn and Madison in Annapolis, Maryland, before returning to work on Fort Adams.[3]

Cullum was promoted to second lieutenant on 20 April 1836. He supervised construction of the facilities on Goat Island until 1838. On 7 July 1838, he was made a captain. Cullum then supervised construction of Fort Trumbull in New London, Connecticut and the lower battery at Fort Griswold in nearby Groton until 1855. He also supervised a number of other projects on the East Coast from 1840 to 1864, including the repairs of sea walls at Deer, Lovells and Rainsford islands; the construction of Forts Warren, Independence, Winthrop and Sumter; the building of cadet barracks at West Point; and the construction of the United States Assay building. He later superintended engineering works on the western rivers.[3]

Cullum was an instructor of practical military engineering at West Point from 1848 to 1851. He then served as director of the Sappers, Miners and Pontoniers at West Point. Cullum published the forerunner of his Biographical Register in 1850. He took two years leave of absence from 1850 to 1852 for health reasons, and traveled throughout Europe, Asia, Africa and the West Indies while recuperating. Cullum then returned to West Point, and taught there until 1855.[3] When Robert E. Lee, at the time superintendent of West Point, went on a vacation to Virginia, Cullum served as acting superintendent of the Academy from 5 July to 27 August 1853.[5]

In 1848, he introduced a type of bridge pontoon, which was used in the Mexican–American War.[6] Cullum published Description of a System of Military Bridges, With India-Rubber Pontons in 1849.[7][8]

Civil War and later military service

On 9 April 1861, Cullum was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel, and shortly after to colonel. He served as an aide-de-camp to General Winfield Scott from 1 April 1861 to 1 November 1861. At the same time he was a member of the United States Sanitary Commission. Cullum was promoted to a Major in the Corps of Engineers, before becoming chief engineer of the Department of the Missouri on 19 November 1861, where he remained until 11 March 1862. Cullum then was chief engineer for the Department of the Mississippi until 11 July.[9]

During the time, he was also the chief of staff for Henry Halleck. He was appointed brigadier general of volunteers on 1 November 1861.[10] From 2 December 1861 to 6 February 1862, Cullum was on the board that inspected the defenses of St. Louis and the board that inspected the condition of the Mississippi Gun and Mortar Boat Flotilla. He travelled to Cairo, Illinois, where he commanded operations auxiliary to various armies in the field and also managed the defense of the District of Cairo. From February to March, he surveyed the Confederate defenses at Columbus, Kentucky.[9]

On 6 February 1862, the Union Army under then Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant captured Fort Henry, and ten days later, on 16 February, they captured Fort Donelson. With these victories, his forces took about 12,000 to 15,000 Confederate prisoners. The army was unprepared to handle this many prisoners and scrambled to find places to house them. Cullum sent many prisoners to St. Louis before he received War Department instructions to direct 7,000 prisoners to Camp Douglas near Chicago.[11] Cullum was chief engineer at the Siege of Corinth.[3]

For the rest of the Civil War, Cullum inspected or built defenses at: Cairo, Illinois; Bird's Point, Missouri; Fort Holt, Kentucky; Columbus, Kentucky; Island Number Ten; New Madrid, Missouri; Corinth, Mississippi; Harpers Ferry, West Virginia; Winchester, Virginia; Martinsburg, West Virginia; Boston Harbor; Nashville, Tennessee; the Potomac aqueduct; Baltimore; and Washington, D.C. He served on boards concerning Timby's Revolving Iron Tower, proposed military bridges, and Army Corps of Engineers officers being considered for promotion. In 1862, Cullum was appointed Chief Engineer of Halleck's armies in the Department of the Missouri.[9]

He was Superintendent of West Point from 1864 to 1866. On 8 March 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated Cullum to be appointed to the grade of brevet major general, USA, to rank from 13 March 1865.[12] He was mustered out of the volunteers on 1 September 1866.[10] In 1867, Cullum published the first edition of his Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy, covering all graduates from the founding of West Point to the class of 1840.[13] The New York Times wrote that "We know of no single contribution to the military history of the Nation so rich in invaluable data and so essential to the future historian or student of American history."[14]

Later life and death

Cullum retired from active service 13 January 1874, with the permanent rank of colonel and the brevet rank of major general,[15] and returned to New York City. Following his retirement, he married Elizabeth Hamilton, sister of Major General Schuyler Hamilton and the wealthy widow of Major General Henry W. Halleck.[7]

Cullum was vice-president of the American Geographical Society, president of the Geographical Library Society of New York and a member of the board of managers of the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor. He was also a member of the Farragut Monument Association, a delegate to the 1881 conferences of the Association for the Reform and Codification of the Law of Nations and of the International Geographical Conference, a corresponding member of the Massachusetts Historical Society, and a member of the American Historical Society and the American Academy.[7] Cullum died on 28 February 1892 in New York City, of pneumonia.[7] He is interred at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn.[16]

Cullum left part of his fortune[a] for the continuance of his Biographical Register and for an award of the American Geographical Society "to those who distinguish themselves by geographical discoveries or in the advancement of geographical science", known as the Cullum Geographical Medal. He also left $250,000 to West Point, "to be used for construction and maintenance of a memorial hall at West Point to be dedicated to the officers and graduates of the U.S. Military Academy".[18] The building is now known as Cullum Hall.[19] Cullum also left $100,000 for a hall for the American Geographical Society.[7]

Dates of rank

| Insignia | Rank[b] | Component[c] | Date | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brevet Second Lieutenant | Corps of Engineers | 1 July 1833 | [15] | |

| Second Lieutenant | Corps of Engineers | 20 April 1836 | [15] | |

| Captain | Corps of Engineers | 7 July 1838 | [15] | |

| Lieutenant‑Colonel | Staff—Aide-de‑Camp to the General-in‑Chief | 9 April 1861 | [15] | |

| Major | Corps of Engineers | 6 August 1861 | [15] | |

| Colonel | Staff—Aide-de‑Camp to the General-in‑Chief | 6 August 1861 | [15] | |

| Brigadier‑General | US Volunteers | 1 November 1861 | [15] | |

| Lieutenant-Colonel | Corps of Engineers | 3 March 1863 | [15] | |

| Brevet Colonel | US Army | 13 March 1865 | [15] | |

| Brevet Brigadier‑General | US Army | 13 March 1865 | [15] | |

| Brevet Major‑General | US Army | 13 March 1865 | [15] | |

| Colonel | Corps of Engineers | 7 March 1867 | [15] |

Publications

- Description of a System of Military Bridges, With India-Rubber Pontons (1849)[8]

- Systems of Military Bridges (1863)[21]

- Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy (1867; third edition, 1891–1910)[21]

- Campaigns and Engineers of the War of 1812–15 (1879)[21]

- Struggle for the Hudson (in the Narrative and Critical History of America, 1887)[21]

- Fortification and Defenses of Narragansett Bay (1888)[7]

- Feudal Castles of France and Spain[7]

See also

- List of American Civil War generals (Union)

- Cullum number (U.S. Military Academy)

- List of superintendents of West Point

References

Notes

- ^ Cullum had accumulated a large amount of money largely from his marrying the widow of Henry Halleck. Halleck had over $500,000 when he died.[17]

- ^ It was possible to hold multiple ranks in the Army at one time. "Many officers of the Regular Army, who held substantive and brevet rank, obtained leaves in order to accept commissions in the volunteer service, where substantive and brevet rank also existed."[20]

- ^ Cullum held a rank in four components of the United States Army. The first was the United States Army Corps of Engineers, the engineering component of the Army. He also held rank as a member of the staff of Henry Halleck. Cullum then had a rank as a brigadier general in the US Volunteers, or the volunteer members of the Army. Also during the Civil War, Cullum held several ranks in the regular army.

Sources

- ^ Assembly. 1959. p. 119.

- ^ Skelton, William B. (2000). "Cullum, George Washington (1809-1892), army officer and author". American National Biography. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0400283. ISBN 978-0-19-860669-7.

- ^ a b c d e Cullum 1891, p. 535.

- ^ "National Historic Landmarks & National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania". CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information System. Archived from the original (Searchable database) on 21 July 2007. Retrieved 18 August 2012. Note: This includes Mrs. Anne Stewart and William K. Watson (August 1977). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Independent Congregational Church" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ "Robert E. Lee (by Freeman) – Vol. I Chap. 19". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ Forrest Bryant Johnson (3 April 2012). The Last Camel Charge: The Untold Story of America's Desert Military Experiment. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-101-56160-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Livermore, William R. (1891). "George W. Cullum". Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 27: 416–421. JSTOR 20020493.

- ^ a b Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society Held at Philadelphia for Promoting Useful Knowledge. The Society. 1847. p. 99.

- ^ a b c Cullum 1891, p. 536.

- ^ a b Eicher & Eicher 2001, p. 720.

- ^ Levy, 1999, pp. 39, 47

- ^ Eicher & Eicher 2001, p. 707.

- ^ "West Point Association of Graduates". West Point Associate of Graduates. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ Bulletin. U.S.M.A. Press. 1900. p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Eicher & Eicher 2001, p. 193.

- ^ Welsh, Jack D. (2005). Medical Histories of Union Generals. Kent State University Press. ISBN 9780873388535.

- ^ Stephen E. Ambrose (December 1999). Duty, Honor, Country: A History of West Point. JHU Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-8018-6293-9.

- ^ United States Congressional Serial Set. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1892.

- ^ "Directorate of Cadet Activities – Cullum Hall History". usma.edu. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ Warner 1964, p. xvi.

- ^ a b c d Cullum 1891, p. 537.

Bibliography

- Cullum, George W. (1891). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point New York since its Establishment in 1802, to 1890: With The early history of the United States Military Academy [volume I]. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1417240. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- Eicher, John H.; Eicher, David J. (2001). Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Cullum, George Washington". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Cullum, George Washington". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.- Warner, Ezra J. (1964). Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge: LSU Press. ISBN 9780807108222. OCLC 855201941.

- Levy, George, To Die in Chicago: Confederate Prisoners at Camp Douglas 1862–1865. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing Company, revised edition 1999, original edition 1994. ISBN 978-1-56554-331-7.