Gestalt theory

| Part of a series on |

| Psychology |

|---|

Gestalt psychology, gestaltism, or configurationism is a school of psychology and a theory of perception that emphasises the processing of entire patterns and configurations, and not merely individual components. It emerged in the early twentieth century in Austria and Germany as a rejection of basic principles of Wilhelm Wundt's and Edward Titchener's elementalist and structuralist psychology.[1][2][3]

Gestalt psychology is often associated with the adage, "The whole is greater than the sum of its parts". In Gestalt theory, information is perceived as wholes rather than disparate parts which are then processed summatively. As used in Gestalt psychology, the German word Gestalt (/ɡəˈʃtælt, -ˈʃtɑːlt/ gə-SHTA(H)LT,[4][5] German: [ɡəˈʃtalt] ⓘ; meaning "form"[6]) is interpreted as "pattern" or "configuration".[7]

It differs from Gestalt therapy, which is only peripherally linked to Gestalt psychology.

Origin and history

Max Wertheimer, Kurt Koffka, and Wolfgang Köhler founded Gestalt psychology in the early 20th century.[8]: 113–116 The dominant view in psychology at the time was structuralism, exemplified by the work of Hermann von Helmholtz, Wilhelm Wundt, and Edward B. Titchener.[9][10]: 3 Structuralism was rooted firmly in British empiricism[9][10]: 3 and was based on three closely interrelated theories:

- "atomism," also known as "elementalism,"[10]: 3 the view that all knowledge, even complex abstract ideas, is built from simple, elementary constituents

- "sensationalism," the view that the simplest constituents—the atoms of thought—are elementary sense impressions

- "associationism," the view that more complex ideas arise from the association of simpler ideas.[10]: 3 [11]

Together, these three theories give rise to the view that the mind constructs all perceptions and abstract thoughts strictly from lower-level sensations, which are related solely by being associated closely in space and time.[9] The Gestaltists took issue with the widespread atomistic view that the aim of psychology should be to break consciousness down into putative basic elements.[6]

In contrast, the Gestalt psychologists believed that breaking psychological phenomena down into smaller parts would not lead to understanding psychology.[8]: 13 Instead, they viewed psychological phenomena as organized, structured wholes.[8]: 13 They argued that the psychological "whole" has priority and that the "parts" are defined by the structure of the whole, rather than the other way round.[12] Gestalt theories of perception are based on human nature being inclined to understand objects as an entire structure rather than the sum of its parts.[13]

Wertheimer had been a student of Austrian philosopher, Christian von Ehrenfels, a member of the School of Brentano. Von Ehrenfels introduced the concept of Gestalt to philosophy and psychology in 1890, before the advent of Gestalt psychology as such.[14][9] Von Ehrenfels observed that a perceptual experience, such as perceiving a melody or a shape, is more than the sum of its sensory components.[9] He claimed that, in addition to the sensory elements of the perception, there is something additional that is an element in its own right, despite in some sense being derived from the organization of the component sensory elements. He called it Gestalt-qualität or "form-quality." It is this Gestalt-qualität that, according to von Ehrenfels, allows a tune to be transposed to a new key, using completely different notes, while still retaining its identity. The idea of a Gestalt-qualität has roots in theories by David Hume, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Immanuel Kant, David Hartley, and Ernst Mach. Both von Ehrenfels and Edmund Husserl seem to have been inspired by Mach's work Beiträge zur Analyse der Empfindungen (Contributions to the Analysis of Sensations, 1886), in formulating their very similar concepts of gestalt and figural moment, respectively.[14]

By 1914, the first published references to Gestalt theory could be found in a footnote of Gabriele von Wartensleben's application of Gestalt theory to personality. She was a student at Frankfurt Academy for Social Sciences, who interacted deeply with Wertheimer and Köhler.[15]

Through a series of experiments, Wertheimer discovered that a person observing a pair of alternating bars of light can, under the right conditions, experience the illusion of movement between one location and the other. He noted that this was a perception of motion absent any moving object. That is, it was pure phenomenal motion. He dubbed it phi ("phenomenal") motion.[14][16] Wertheimer's publication of these results in 1912[17] marks the beginning of Gestalt psychology.[16] In comparison to von Ehrenfels and others who had used the term "gestalt" earlier in various ways, Wertheimer's unique contribution was to insist that the "gestalt" is perceptually primary. The gestalt defines the parts from which it is composed, rather than being a secondary quality that emerges from those parts.[16] Wertheimer took the more radical position that one hears the melody first and only then may perceptually divide it up into notes. Similarly, in vision, one sees the form of the circle first, with its apprehension not mediated by a process of part-summation. Only after this primary apprehension might one notice that it is made up of lines or dots or stars.

The two men who served as Wertheimer's subjects in the phi experiments were Köhler and Koffka. Köhler was an expert in physical acoustics, having studied under physicist Max Planck, but had taken his degree in psychology under Carl Stumpf. Koffka was also a student of Stumpf's, having studied movement phenomena and psychological aspects of rhythm. In 1917, Köhler published the results of four years of research on learning in chimpanzees. Köhler showed, contrary to the claims of most other learning theorists, that animals can learn by "sudden insight" into the "structure" of a problem, over and above the associative and incremental manner of learning that Ivan Pavlov and Edward Lee Thorndike had demonstrated with dogs and cats, respectively.

In 1921, Koffka published a Gestalt-oriented text on developmental psychology, Growth of the Mind. With the help of American psychologist Robert Ogden, Koffka introduced the Gestalt point of view to an American audience in 1922 by way of a paper in Psychological Bulletin. It contains criticisms of then-current explanations of a number of problems of perception, and the alternatives offered by the Gestalt school. Koffka moved to the United States in 1924, eventually settling at Smith College in 1927. In 1935, Koffka published his Principles of Gestalt Psychology. This textbook laid out the Gestalt vision of the scientific enterprise as a whole. Science, he said, is not the simple accumulation of facts. What makes research scientific is the incorporation of facts into a theoretical structure. The goal of the Gestaltists was to integrate the facts of inanimate nature, life, and mind into a single scientific structure. This meant that science would have to accommodate not only what Koffka called the quantitative facts of physical science but the facts of two other "scientific categories": questions of order and questions of Sinn, a German word which has been variously translated as significance, value, and meaning. Without incorporating the meaning of experience and behavior, Koffka believed that science would doom itself to trivialities in its investigation of human beings.

Having survived the Nazis up to the mid-1930s,[18] all the core members of the Gestalt movement were forced out of Germany to the United States by 1935.[19] Köhler published another book, Dynamics in Psychology, in 1940 but thereafter the Gestalt movement suffered a series of setbacks. Koffka died in 1941 and Wertheimer in 1943. Wertheimer's long-awaited book on mathematical problem-solving, Productive Thinking, was published posthumously in 1945, but Köhler was left to guide the movement without his two long-time colleagues.[note 1]

Gestalt therapy

Gestalt psychology differs from Gestalt therapy, which is only peripherally linked to Gestalt psychology. The founders of Gestalt therapy, Fritz and Laura Perls, had worked with Kurt Goldstein, a neurologist who had applied principles of Gestalt psychology to the functioning of the organism. Laura Perls had been a Gestalt psychologist before she became a psychoanalyst and before she began developing Gestalt therapy together with Fritz Perls.[20] The extent to which Gestalt psychology influenced Gestalt therapy is disputed. On one hand, Laura Perls preferred not to use the term "Gestalt" to name the emerging new therapy, because she thought that the Gestalt psychologists would object to it;[21] on the other hand, Fritz and Laura Perls clearly adopted some of Goldstein's work.[22]

Mary Henle noted in her presidential address to Division 24 at the meeting of the American Psychological Association: "What Perls has done has been to take a few terms from Gestalt psychology, stretch their meaning beyond recognition, mix them with notions—often unclear and often incompatible—from the depth psychologies, existentialism, and common sense, and he has called the whole mixture gestalt therapy. His work has no substantive relation to scientific Gestalt psychology. To use his own language, Fritz Perls has done 'his thing'; whatever it is, it is not Gestalt psychology."[23]

One form of psychotherapy that, unlike Gestalt therapy, is actually consistently based on Gestalt psychology is Gestalt theoretical psychotherapy.

Theoretical framework and methodology

The Gestalt psychologists practiced a set of theoretical and methodological principles that attempted to redefine the approach to psychological research. This is in contrast to investigations developed at the beginning of the 20th century, based on traditional scientific methodology, which divided the object of study into a set of elements that could be analyzed separately with the objective of reducing the complexity of this object.

The principle of totality asserts that conscious experience must be considered globally by taking into account all the physical and mental aspects of the individual simultaneously, because the nature of the mind demands that each component be considered as part of a system of dynamic relationships. Thus, holism as fundamental aspect of Gestalt psychology.[9][24] Moreover, the perception of the nature of a part depends upon the whole in which it is embedded.[9][25] The maxim that the whole is more than the sum of its parts is not a precise description of the Gestaltist view.[9] Rather, as Koffka writes, "The whole is something else than the sum of its parts, because summing is a meaningless procedure, whereas the whole-part relationship is meaningful."[26]

The principle of psychophysical isomorphism hypothesizes that there is a correlation between conscious experience and cerebral activity.[16]

Based on the principles, phenomenon experimental analysis was derived, which asserts that any psychological research should take phenomena as a starting point and not be solely focused on sensory qualities. A related principle is that of the biotic experiment, which establishes the need to conduct real experiments that sharply contrasted with and opposed classic laboratory experiments. This signified experimenting in natural situations, developed in real conditions, in which it would be possible to reproduce, with higher fidelity, what would be habitual for a subject.[27]

Principles

The Gestaltists were the first to document and demonstrate empirically many facts about perception—including facts about the perception of movement, the perception of contour, perceptual constancy, and perceptual illusions.[14] Wertheimer's discovery of the phi phenomenon is one example of such a contribution.[28]

Properties

The key principles of gestalt systems are emergence, reification, multistability and invariance.[29] These principles are not necessarily separable modules to model individually, but they could be different aspects of a single unified dynamic mechanism.[30]

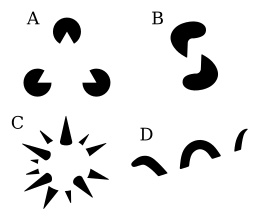

Reification

Reification is the constructive or generative aspect of perception, by which the experienced object of perception contains more explicit spatial information than the sensory stimulus on which it is based. For instance, a triangle is perceived in picture A, though no triangle is there. In pictures B and D the eye recognizes disparate shapes as "belonging" to a single shape, in C a complete three-dimensional shape is seen, where in actuality no such thing is drawn.

Reification can be explained by progress in the study of illusory contours, which are treated by the visual system as "real" contours.

Multistability

Multistability (or multistable perception) is the tendency of ambiguous perceptual experiences to pop back and forth between two or more alternative interpretations. This is seen, for example, in the Necker cube and Rubin's Figure/Vase illusion. Other examples include the three-legged blivet, artist M. C. Escher's artwork, and the appearance of flashing marquee lights moving first one direction and then suddenly the other.

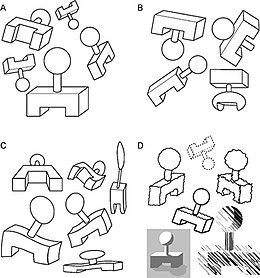

Invariance

Invariance is the property of perception whereby simple geometrical objects are recognized independent of rotation, translation, and scale, as well as several other variations such as elastic deformations, different lighting, and different component features. For example, the objects in A in the figure are all immediately recognized as the same basic shape, which is immediately distinguishable from the forms in B. They are even recognized despite perspective and elastic deformations as in C, and when depicted using different graphic elements as in D. Computational theories of vision, such as those by David Marr, have provided alternate explanations of how perceived objects are classified.

Perceptual organisation forms

Perceptual grouping

Like figure-ground organization, perceptual grouping (sometimes called perceptual segregation)[31] is a form of perceptual organization.[16] Perceptual grouping is the process that determines how organisms perceive some parts of their perceptual fields as being more related than others,[16] using such information for object detection.[31]

The Gestaltists were the first psychologists to systematically study perceptual grouping.[31] According to Gestalt psychologists, the fundamental principle of perceptual grouping is the law of Prägnanz,[31] also known as the law of good Gestalt. Prägnanz is a German word that directly translates to "pithiness" and implies salience, conciseness, and orderliness.[32] The law of Prägnanz says that people tend to experience things as regular, orderly, symmetrical, and simple.[33]

Gestalt psychologists attempted to discover refinements of the law of Prägnanz, which involved writing down laws that predict the interpretation of sensation.[34] Wertheimer defined a few principles that explain the ways humans perceive objects based on similarity, proximity, and continuity.[35]

Law of proximity

The law of proximity states that when an individual perceives an assortment of objects, they perceive objects that are close to each other as forming a group. For example, in the figure illustrating the law of proximity, there are 72 circles, but we perceive the collection of circles in groups. Specifically, we perceive that there is a group of 36 circles on the left side of the image and three groups of 12 circles on the right side of the image. This law is often used in advertising logos to emphasize which aspects of events are associated.[36][37]

Law of similarity

The law of similarity states that elements within an assortment of objects are perceptually grouped together if they are similar to each other. This similarity can occur in the form of shape, colour, shading or other qualities. For example, the figure illustrating the law of similarity portrays 36 circles all equal distance apart from one another forming a square. In this depiction, 18 of the circles are shaded dark, and 18 of the circles are shaded light. We perceive the dark circles as grouped together and the light circles as grouped together, forming six horizontal lines within the square of circles. This perception of lines is due to the law of similarity.[37]

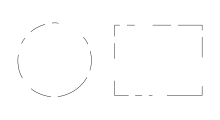

Law of closure

Gestalt psychologists believed that humans tend to perceive objects as complete rather than focusing on the gaps that the object might contain.[38] For example, a circle has good Gestalt in terms of completeness. However, we will also perceive an incomplete circle as a complete circle.[39] That tendency to complete shapes and figures is called closure.[39] The law of closure states that individuals perceive objects such as shapes, letters, pictures, etc., as being whole when they are not complete. Specifically, when parts of a whole picture are missing, our perception fills in the visual gap. Research shows that the reason the mind completes a regular figure that is not perceived through sensation is to increase the regularity of surrounding stimuli. For example, the figure that depicts the law of closure portrays what we perceive as a circle on the left side of the image and a rectangle on the right side of the image. However, gaps are present in the shapes. If the law of closure did not exist, the image would depict an assortment of different lines with different lengths, rotations, and curvatures—but with the law of closure, we perceptually combine the lines into whole shapes.[36][37][40]

Law of symmetry

The law of symmetry states that the mind perceives objects as being symmetrical and forming around a center point. It is perceptually pleasing to divide objects into an even number of symmetrical parts. Therefore, when two symmetrical elements are unconnected the mind perceptually connects them to form a coherent shape. Similarities between symmetrical objects increase the likelihood that objects are grouped to form a combined symmetrical object. For example, the figure depicting the law of symmetry shows a configuration of square and curled brackets. When the image is perceived, we tend to observe three pairs of symmetrical brackets rather than six individual brackets.[36][37]

Law of common fate

The law of common fate states that objects are perceived as lines that move along the smoothest path. Experiments using the visual sensory modality found that the movement of elements of an object produces paths that individuals perceive that the objects are on. We perceive elements of objects to have trends of motion, which indicate the path that the object is on. The law of continuity implies the grouping together of objects that have the same trend of motion and are therefore on the same path. For example, if there is an array of dots and half the dots are moving upward while the other half are moving downward, we would perceive the upward moving dots and the downward moving dots as two distinct units.[32]

Law of continuity

The law of continuity (also known as the law of good continuation) states that elements of objects tend to be grouped together, and therefore integrated into perceptual wholes if they are aligned within an object. In cases where there is an intersection between objects, individuals tend to perceive the two objects as two single uninterrupted entities. Stimuli remain distinct even with overlap. We are less likely to group elements with sharp abrupt directional changes as being one object. For example, the figure depicting the law of continuity shows a configuration of two crossed keys. When the image is perceived, we tend to perceive the key in the background as a single uninterrupted key instead of two separate halves of a key.[36]

Law of past experience

The law of past experience implies that under some circumstances visual stimuli are categorized according to past experience. If objects tend to be observed within close proximity, or small temporal intervals, the objects are more likely to be perceived together. For example, the English language contains 26 letters that are grouped to form words using a set of rules. If an individual reads an English word they have never seen, they use the law of past experience to interpret the letters "L" and "I" as two letters beside each other, rather than using the law of closure to combine the letters and interpret the object as an uppercase U.[32]

Music

An example of the Gestalt movement in effect, as it is both a process and result, is a music sequence. People are able to recognise a sequence of perhaps six or seven notes, despite them being transposed into a different tuning or key.[41] An early theory of gestalt grouping principles in music was composer-theorist James Tenney's Meta+Hodos (1961).[42] Auditory Scene Analysis as developed by Albert Bregman further extends a gestalt approach to the analysis of sound perception.

Figure-ground organization

Figure-ground organization is a form of perceptual organization, which interprets perceptual elements in terms of their shapes and relative locations in the layout of surfaces in the 3-D world.[16] Figure-ground organization structures the perceptual field into a figure (standing out at the front of the perceptual field) and a background (receding behind the figure).[39] Pioneering work on figure-ground organization was carried out by the Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin. The Gestalt psychologists demonstrated that people tend to perceive as figures those parts of our perceptual fields that are convex, symmetric, small, and enclosed.[16]

Problem solving and insight

Gestalt psychology contributed to the scientific study of problem solving.[28] In fact, the early experimental work of the Gestaltists in Germany[note 2] marks the beginning of the scientific study of problem solving. Later this experimental work continued through the 1960s and early 1970s with research conducted on relatively simple laboratory tasks of problem solving.[note 3][43]

Max Wertheimer distinguished two kinds of thinking: productive thinking and reproductive thinking.[8]: 456 [44][45]: 361 Productive thinking is solving a problem based on insight—a quick, creative, unplanned response to situations and environmental interaction. Reproductive thinking is solving a problem deliberately based on previous experience and knowledge. Reproductive thinking proceeds algorithmically—a problem solver reproduces a series of steps from memory, knowing that they will lead to a solution—or by trial and error.[45]: 361

Karl Duncker, another Gestalt psychologist who studied problem solving,[45]: 370 coined the term functional fixedness for describing the difficulties in both visual perception and problem solving that arise from the fact that one element of a whole situation already has a (fixed) function that has to be changed in order to perceive something or find the solution to a problem.[46]

Legacy

Gestalt psychology struggled to precisely define terms like Prägnanz, to make specific behavioural predictions, and to articulate testable models of underlying neural mechanisms.[9] It was criticized as being merely descriptive.[47] These shortcomings led, by the mid-20th century, to growing dissatisfaction with Gestaltism and a subsequent decline in its impact on psychology.[9] Despite this decline, Gestalt psychology has formed the basis of much further research into the perception of patterns and objects[48] and of research into behaviour, thinking, problem solving and psychopathology.

Support from cybernetics and neurology

In the 1940s and 1950s, laboratory research in neurology and what became known as cybernetics on the mechanism of frogs' eyes indicate that perception of 'gestalts' (in particular gestalts in motion) is perhaps more primitive and fundamental than 'seeing' as such:

- A frog hunts on land by vision... He has no fovea, or region of greatest acuity in vision, upon which he must centre a part of the image... The frog does not seem to see or, at any rate, is not concerned with the detail of stationary parts of the world around him. He will starve to death surrounded by food if it is not moving. His choice of food is determined only by size and movement. He will leap to capture any object the size of an insect or worm, providing it moves like one. He can be fooled easily not only by a piece of dangled meat but by any moving small object... He does remember a moving thing provided it stays within his field of vision and he is not distracted.[49]

- The lowest-level concepts related to visual perception for a human being probably differ little from the concepts of a frog. In any case, the structure of the retina in mammals and in human beings is the same as in amphibians. The phenomenon of distortion of perception of an image stabilised on the retina gives some idea of the concepts of the subsequent levels of the hierarchy. This is a very interesting phenomenon. When a person looks at an immobile object, "fixes" it with his eyes, the eyeballs do not remain absolutely immobile; they make small involuntary movements. As a result, the image of the object on the retina is constantly in motion, slowly drifting and jumping back to the point of maximum sensitivity. The image "marks time" in the vicinity of this point.[50]

Use in contemporary social psychology

The halo effect can be explained through the application of Gestalt theories to social information processing.[51][13] The constructive theories of social cognition are applied to the expectations of individuals. They have been perceived in this manner and the person judging the individual is continuing to view them in this positive manner.[13] Gestalt's theories of perception enforces that individual's tendency to perceive actions and characteristics as a whole rather than isolated parts,[13] therefore humans are inclined to build a coherent and consistent impression of objects and behaviors in order to achieve an acceptable shape and form. The halo effect is what forms patterns for individuals,[13] the halo effect being classified as a cognitive bias which occurs during impression formation.[51] The halo effect can also be altered by physical characteristics, social status and many other characteristics.[52] As well, the halo effect can have real repercussions on the individual's perception of reality, either negatively or positively, meaning to construct negative or positive images about other individuals or situations, something that could lead to self-fulfilling prophesies, stereotyping, or even discrimination.[13]

Contemporary cognitive and perceptual psychology

Some of the central criticisms of Gestaltism are based on the preference Gestaltists are deemed to have for theory over data, and a lack of quantitative research supporting Gestalt ideas. This is not necessarily a fair criticism as highlighted by a recent collection of quantitative research on Gestalt perception.[53] Researchers continue to test hypotheses about the mechanisms underlying Gestalt principles such as the principle of similarity.[54]

Other important criticisms concern the lack of definition and support for the many physiological assumptions made by gestaltists[55] and lack of theoretical coherence in modern Gestalt psychology.[53]

In some scholarly communities, such as cognitive psychology and computational neuroscience, gestalt theories of perception are criticized for being descriptive rather than explanatory in nature. For this reason, they are viewed by some as redundant or uninformative. For example, a textbook on visual perception states that, "The physiological theory of the gestaltists has fallen by the wayside, leaving us with a set of descriptive principles, but without a model of perceptual processing. Indeed, some of their 'laws' of perceptual organisation today sound vague and inadequate. What is meant by a 'good' or 'simple' shape, for example?"[47]

One historian of psychology, David J. Murray, has argued that Gestalt psychologists first discovered many principles later championed by cognitive psychology, including schemas and prototypes.[56] Another psychologist has argued that the Gestalt psychologists made a lasting contribution by showing how the study of illusions can help scientists understand essential aspects of how the visual system normally functions, not merely how it breaks down.[10]: 16

Use in design

The gestalt laws are used in several visual design fields, such as user interface design and cartography. The laws of similarity and proximity can, for example, be used as guides for placing radio buttons. They may also be used in designing computers and software for more intuitive human use. Examples include the design and layout of a desktop's shortcuts in rows and columns.[37]

In map design, principles of Prägnanz or grouping are crucial for implying a conceptual order to the portrayed geographic features, thus facilitating the intended use of the map.[57] The Law of Similarity is employed by selecting similar map symbols for similar kinds of features or features with similar properties; the Law of Proximity is crucial to identifying geographic patterns and regions; and the Laws of Closure and Continuity allow users to recognize features that may be obscured by other features (such as when a road goes over a river).

See also

- Augusto Garau

- Amodal perception

- Cognitive grammar

- Egregore

- Gestaltzerfall

- Graz School

- Hans Wallach

- Hermann Friedmann

- James J. Gibson

- James Tenney

- Laws of association

- Mereology

- Optical illusion

- Pál Schiller Harkai

- Pattern recognition (machine learning)

- Pattern recognition (psychology)

- Phenomenology

- Principles of grouping

- Rudolf Arnheim

- Solomon Asch

- Structural information theory

- Topological data analysis

- Wolfgang Metzger

- Vera Felicidade de Almeida Campos

Notes

- ^ For more on the history of Gestalt psychology, see Ash, M. G. (1995). Gestalt psychology in German culture, 1890–1967: Holism and the quest for objectivity. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press..

- ^ For example, Duncker, Karl (1935). Zur Psychologie des produktiven Denkens [The psychology of productive thinking] (in German). Berlin: Julius Springer.

- ^ For example Duncker's "X-ray" problem; Ewert & Lambert's "disk" problem in 1932, later known as Tower of Hanoi.

References

- ^ Mather, George (2006). Foundations of Perception. Psychology Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-86377-834-6.

- ^ "Gestalt psychology". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Baker, David B., ed. (13 January 2012). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Psychology: Global Perspectives. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 576. ISBN 978-0-19-536655-6.

- ^ Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ "Definition of gestalt | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Gestalt". The Columbia Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. 2018. ISBN 9781786848468. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ "Gestalt psychology". Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 1 May 2008. p. 756. ISBN 9781593394929. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d Sternberg, Robert J.; Sternberg, Karin (2012). Cognitive Psychology (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-133-31391-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Wagemans, Johan; Feldman, Jacob; Gepshtein, Sergei; Kimchi, Ruth; Pomerantz, James R.; van der Helm, Peter A.; van Leeuwen, Cees (2012). "A century of Gestalt psychology in visual perception: II. Conceptual and theoretical foundations". Psychological Bulletin. 138 (6): 1218–1252. doi:10.1037/a0029334. ISSN 1939-1455. PMC 3728284. PMID 22845750.

- ^ a b c d e Kolers, Paul A. (1972). Aspects of Motion Perception: International Series of Monographs in Experimental Psychology. New York: Pergamon. ISBN 978-1-4831-7113-5.

- ^ Hamlyn, D. W. (1957). The Psychology of Perception: A Philosophical Examination of Gestalt Theory and Derivative Theories of Perception (eBook ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-1-315-47329-1. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ Verstegen, Ian (2010). "Gestalt Psychology". The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. pp. 1–3. doi:10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0386. ISBN 9780470479216.

- ^ a b c d e f Pohl, Rüdiger F. (22 July 2016). Cognitive Illusions: Intriguing Phenomena in Judgement, Thinking and Memory. Psychology Press. ISBN 9781317448280. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d Smith, Barry (1988). "Gestalt Theory: An Essay in Philosophy". In Smith, Barry (ed.). Foundations of Gestalt Theory. Vienna: Philosophia Verlag. pp. 11–81. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ King, D. Brett; Wertheimer, Michael (1 January 2005). Max Wertheimer and Gestalt Theory. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-2826-0. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wagemans, Johan; Elder, James H.; Kubovy, Michael; Palmer, Stephen E.; Peterson, Mary A.; Singh, Manish; von der Heydt, Rüdiger (2012). "A century of Gestalt psychology in visual perception: I. Perceptual grouping and figure-ground organization". Psychological Bulletin. 138 (6): 1172–1217. doi:10.1037/a0029333. ISSN 1939-1455. PMC 3482144. PMID 22845751.

- ^ Wertheimer, Max (1912). "Experimentelle Studien über das Sehen von Bewegung" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Psychologie (in German). 61: 161–265. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2019. Available in translation as Wertheimer, Max (2012). "Experimental Studies on Seeing Motion". In Spillman, Lothar (ed.). On Perceived Motion and Figural Organization. Michael Wertheimer, K. W. Watkins (trans.). Cambridge, MA: MIT.

- ^ Henle, M (1978). "One man against the Nazis: Wolfgang Köhler" (PDF). American Psychologist. 33 (10): 939–944. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.33.10.939. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002B-9E5F-5. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ Henle, M (1984). "Robert M. Ogden and gestalt psychology in America". Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 20 (1): 9–19. doi:10.1002/1520-6696(198401)20:1<9::aid-jhbs2300200103>3.0.co;2-u. PMID 11608590.

- ^ Bocian, B. (2010). Fritz Perls in Berlin 1893–1933: Expressionism – Psychoanalysis – Judaism. EHP – Edition Humanistische Psychology. p. 190. ISBN 978-3-89797-068-7.

- ^ Joe Wysong/Edward Rosenfeld (eds): An Oral History of Gestalt Therapy, Highland, New York 1982, The Gestalt Journal Press, p. 12.

- ^ Barlow, Allen R. (Fall 1981). "Gestalt—Antecedent Influence or Historical Accident". The Gestalt Journal. 4 (2). Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Mary Henle 1975: Gestalt Psychology and Gestalt Therapy Archived 5 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine; Presidential Address to Division 24 at the meeting of the American Psychological Association, Chicago, September 1975. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 14, pp 23–32.

- ^ Wertheimer, Max (1938) [Original work published 1924]. "Gestalt theory". In Ellis, Willis D. (ed.). A Source Book of Gestalt Psychology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 2. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ Köhler, Wolfgang (1971) [Original work published 1930]. "Human perception". In Henle, Mary (ed.). The Selected Papers of Wolfgang Köhler. Liveright. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-87140-253-0.

- ^ Koffka, K. (1935). Principles of Gestalt Psychology. New York: Harcourt, Brace. pp. 176. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ William Ray Woodward, Robert Sonné Cohen – World views and scientific discipline formation: science studies in the German Democratic Republic: papers from a German-American summer institute, 1988

- ^ a b Gobet, Fernand (2017), "Entrenchment, Gestalt formation, and chunking", in Schmid, H. J. (ed.), Entrenchment and the psychology of language learning: How we reorganize and adapt linguistic knowledge, American Psychological Association, pp. 245–267, doi:10.1037/15969-012, ISBN 978-3110341300, archived from the original on 26 February 2022, retrieved 14 October 2019

- ^ Steven., Lehar (2003). The World in your Head: A Gestalt View of the Mechanism of Conscious Experience. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. ISBN 0805841768. OCLC 52051454. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2005.

- ^ "Gestalt Isomorphism". Sharp.bu.edu. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d Eysenck, Michael W. (2006). Fundamentals of Cognition. Hove, UK: Psychology Press. pp. 62–64. ISBN 978-1-84169-374-3.

- ^ a b c Todorovic, Dejan (2008). "Gestalt Principles". Scholarpedia. 3 (12): 5345. Bibcode:2008SchpJ...3.5345T. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.5345.

- ^ Koffka, K. (1935). Principles Of Gestalt Psychology. New York: Harcourt, Brace. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ Sternberg, Robert (2003). Cognitive psychology (3rd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-15-508535-0. OCLC 883578008.

- ^ Craighead, W. Edward; Nemeroff, Charles B. (19 April 2004). "Gestalt psychology". The Concise Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology and Behavioral Science. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 401–404. ISBN 9780471220367. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d Stevenson, Herb. "Emergence: The Gestalt Approach to Change". Unleashing Executive and Orzanizational Potential. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Soegaard, Mads. Gestalt Principles of form Perception. Interaction Design. Archived from the original on 10 April 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ^ Hamlyn, D. W. (27 March 2017). The Psychology of Perception. doi:10.4324/9781315473291. ISBN 9781315473291.

- ^ a b c Brennan, James F.; Houde, Keith A. (26 October 2017). History and Systems of Psychology. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316827178. ISBN 9781107178670. S2CID 142935847.

- ^ "Why Your Brain Thinks These Dots Are a Dog". Gizmodo UK. 17 May 2013. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Ellis, Willis D. (1999). A source book of Gestalt psychology. Vol. 2. Psychology Press.

- ^ Tenney, James. (1961) 2015. “Meta+Hodos.” In From Scratch: Writings in Music Theory. Edited by Larry Polansky, Lauren Pratt, Robert Wannamaker, and Michael Winter. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. 13–96.

- ^ Mayer, R. E. (1992). Thinking, problem solving, cognition. Second edition. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

- ^ Wertheimer, Max (1945). Productive thinking. New York: Harper.

- ^ a b c Kellogg, Ronald T. (2003). Cognitive Psychology (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. ISBN 0-7619-2130-3.

- ^ Duncker, Karl (1935). Zur Psychologie des produktiven Denkens [The psychology of productive thinking] (in German). Berlin: Julius Springer.

- ^ a b Bruce, V.; Green, P.; Georgeson, M. (1996). Visual perception: Physiology, psychology and ecology (3rd ed.). LEA. p. 110.

- ^ Carlson, Neil R.; Heth, C. Donald (2010). Psychology: The Science of Behaviour. Ontario: Pearson Education Canada. pp. 20–22.

- ^ Lettvin, J.Y., Maturana, H.R., Pitts, W.H., and McCulloch, W.S. (1961). Two Remarks on the Visual System of the Frog. In Sensory Communication edited by Walter Rosenblith, MIT Press and John Wiley and Sons: New York

- ^ Valentin Fedorovich Turchin – The phenomenon of science – a cybernetic approach to human evolution – Columbia University Press, 1977

- ^ a b Nauts, Sanne; Langner, Oliver; Huijsmans, Inge; Vonk, Roos; Wigboldus, Daniël H. J. (2014). "Forming Impressions of Personality: A Replication and Review of Evidence for a Primacy-of-Warmth Effect in Impression Formation". Social Psychology. 45 (3): 153–163. doi:10.1027/1864-9335/a000179. hdl:2066/128034. ISSN 1864-9335. S2CID 7693277.

- ^ Sigall, Harold; Ostrove, Nancy (1975). "Beautiful but dangerous: Effects of offender attractiveness and nature of the crime on juridic judgment". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 31 (3): 410–414. doi:10.1037/h0076472. ISSN 0022-3514.

- ^ a b Jäkel F.; Singh M.; Wichmann F. A.; Herzog, M. H. (2016), "An overview of quantitative approaches in Gestalt perception.", Vision Research, 126: 3–8, doi:10.1016/j.visres.2016.06.004, PMID 27353224

- ^ Yu, Dian; Tam, Derek; Franconeri, Steven L. (2019). "Gestalt similarity groupings are not constructed in parallel". Cognition. 182: 8–13. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2018.08.006. ISSN 0010-0277. PMID 30212653. S2CID 52269830.

- ^ Schultz, Duane (2013). A History of Modern Psychology. Burlington: Elsevier Science. p. 291. ISBN 978-1483270081.

- ^ Murray, David J. (1995). Gestalt Psychology and the Cognitive Revolution. New York: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-320714-9.

- ^ Tait, Alex (1 April 2018). "Visual Hierarchy and Layout". Geographic Information Science & Technology Body of Knowledge. 2018 (Q2). University Consortium for Geographic Information Science. doi:10.22224/gistbok/2018.2.4. ISSN 2577-2848.

- Heider, Grace M. (1977). "More about Hull and Koffka". American Psychologist. 32 (5). American Psychological Association: 383. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.32.5.383.a. ISSN 1935-990X.