Great Seljuk architecture

From top to bottom: Dome of Taj al-Mulk in the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan (1088–1089); Mausoleum of Sultan Sanjar in Merv (c. 1152); Iwans at the Jameh Mosque of Ardestan (c. 1158–1160) | |

| Years active | c. 11th–12th centuries |

|---|---|

Great Seljuk architecture, or simply Seljuk architecture,[a] refers to building activity that took place under the Great Seljuk Empire (11th–12th centuries). The developments of this period contributed significantly to the architecture of Iran, the architecture of Central Asia, and that of nearby regions. It introduced innovations such as the symmetrical four-iwan layout in mosques, advancements in dome construction, early use of muqarnas, and the first widespread creation of state-sponsored madrasas. Their buildings were generally constructed in brick, with decoration created using brickwork, tiles, and carved stucco.

Historical background

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Iran |

|---|

|

|

|

The Seljuk Turks created the Great Seljuk Empire in the 11th century, conquering all of Iran and other extensive territories from the Hindu Kush to eastern Anatolia and from Central Asia to the Persian Gulf. In 1050 Isfahan was established as capital of the Great Seljuk Empire under Alp Arslan.[1] In 1071, following the Seljuk victory over the Byzantine Empire at the Battle of Manzikert, Anatolia was opened up to Turkic settlers.[2][3] The center of Seljuk architectural patronage was Iran, where the first permanent Seljuk edifices were constructed.[4] The cultural apogee of the Great Seljuk state is associated with the reign of Malik-Shah I (r. 1072–1092) and the tenure of Nizam al-Mulk as his vizier. Among other policies, Nizam al-Mulk championed Sunnism over Shiism and founded a network of madrasas as an instrument for this policy.[5] This marked the beginning of the madrasa as an institution that spread across the Sunni Islamic world. Although no Seljuk madrasas have been preserved intact today, the architectural design of Seljuk madrasas in Iran likely influenced the design of madrasas elsewhere.[6][7]

While the apogee of the Great Seljuks was short-lived, it represents a major benchmark in the history of Islamic art and architecture in the region of Greater Iran, inaugurating an expansion of patronage and of artistic forms.[8][9] Much of the Seljuk architectural heritage was destroyed as a result of the Mongol invasions in the 13th century.[10] Nonetheless, compared to pre-Seljuk Iran, a much greater volume of surviving monuments and artifacts from the Seljuk period has allowed scholars to study the arts of this era in much greater depth than preceding periods.[8][9] The period of the 11th to 13th centuries is also considered a "classical era" of Central Asian architecture, marked by a high quality of construction and decoration.[11] Here the Seljuk capital was Merv, which remained the artistic center of the region during this period.[11] The region of Transoxiana, north of the Oxus, was ruled by the Qarakhanids, a rival Turkic dynasty who became vassals of the Seljuks during Malik-Shah's reign.[12] This dynasty also contributed to the flourishing of architecture in Central Asia at this time, building in a style very similar to the Seljuks.[13][9][8] Similarly, to the east of the Great Seljuk Empire the Ghaznavids and their successors, the Ghurids, built in a closely related style.[9][8] A general tradition of architecture was thus shared across most of the eastern Islamic world (Iran, Central Asia, and parts of the northern Indian subcontinent) throughout the Seljuk period and its decline, from the 11th to 13th centuries.[8][9]

After the decline of the Great Seljuks in the late 12th century various Turkic dynasties formed smaller states and empires. A branch of the Seljuk dynasty ruled a Sultanate in Anatolia (also known as the Anatolian Seljuks or Seljuks of Rum), the Zengids and Artuqids ruled in Upper Mesopotomia (known as al-Jazira) and nearby regions, and the Khwarazmian Empire ruled over Iran and Central Asia until the Mongol invasions of the 13th century.[14] Under Zengid and Artuqid rule, the cities of Upper Mesopotamia became important centers of architectural development that influenced the wider region.[15][16] Zengid rule in Syria also helped to spread architectural forms from the eastern Islamic world to this region.[17] In Anatolia, the Seljuks of Rum oversaw the construction of monuments reflecting a diverse array of influences, drawing on both the eastern Islamic world and on more local Byzantine, Armenian, and Georgian sources.[18][19]

Forms and building types

Mosques

The most important religious monument from the Great Seljuk period is the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan, which was expanded and modified by various Seljuk patrons in the late 11th century and early 12th century. Two major and innovative domed chambers were added to it in the late 11th century: the south dome (in front of the mihrab) was commissioned by Nizam al-Mulk in 1086–87 and the north dome was commissioned by Taj al-Mulk in 1088–89. Four large iwans were later erected around the courtyard around the early 12th century, giving rise to the four-iwan plan.[20][21][22] These additions constitute some of the most important architectural innovations of the Seljuk period.[23]

The four-iwan plan already had roots in ancient Iranian architecture and has been found in some Parthian and Sasanian palaces.[24] Soon after or around the same time as the Seljuk work in Isfahan, it appeared in other mosques such as the Jameh Mosque of Zavareh (built circa 1135–1136) and the Jameh Mosque of Ardestan (renovated by a Seljuk vizier in 1158–1160).[25] It subsequently became the "classic" form of Iranian Friday (Jameh) mosques.[24]

The transformation of the space in front of the mihrab (or the maqsura) into a monumental domed hall also proved to be influential, becoming a common feature of future Iranian and Central Asian mosques. It also features in later mosques in Egypt, Anatolia, and beyond.[23] Both of the domes added to the Isfahan mosque also employ a new type of squinch consisting of a barrel vault above a pair of quarter-domes,[22] which was related to early muqarnas forms.[26] The north dome of the Isfahan mosque, in particular, is considered a masterpiece of medieval Iranian architecture, with the interlacing ribs of the dome and the vertically aligned elements of the supporting walls achieving a great elegance.[22][20]

Another innovation by the Seljuks was the "kiosk mosque".[27][additional citation(s) needed] This usually small edifice is characterised by an unusual plan consisting of a domed hall, standing on arches with three open sides giving it the kiosk character. Furthermore, the minarets constructed by the Seljuks took a new dimension adopting an Iranian preference of cylindrical form featuring elaborate patterns.[28] This style was substantially different from the typical square shaped North African minarets.[28]

Madrasas

In the late 11th century the Seljuk vizier Nizam al-Mulk (in office between 1064 and 1092) created a system of state madrasas called the Niẓāmiyyahs (named after him) in various Seljuk and Abbasid cities ranging from Mesopotamia to Khorasan.[7][6] Practically none of these madrasas founded under Nizam al-Mulk have survived, though partial remains of one madrasa in Khargerd, Iran, include an iwan and an inscription attributing it to Nizam al-Mulk. Nonetheless, it is clear that the Seljuks constructed many madrasas across their empire within a relatively short period of time, thus spreading both the idea of this institution and the architectural models on which later examples were based.[6][7] Although madrasa-type institutions appear to have existed in Iran before Nizam al-Mulk, this period is nonetheless considered by many as the starting point for the proliferation of the first formal madrasas across the rest of the Muslim world.[29][6][7]

André Godard also attributed the origin and spread of the four-iwan plan to the appearance of these madrasas and he argued that the layout was derived from the domestic architecture indigenous to Khorasan.[30][31] Godard's origin theory has not been accepted by all scholars,[25] but it is widely-attested that the four-iwan layout did spread to other regions alongside the spread of madrasas across the Islamic world.[6][7][23]

Caravanserais

Large caravanserais were built as a way to foster trade and assert Seljuk authority in the countryside. They typically consisted of a building with a fortified exterior appearance, monumental entrance portal, and interior courtyard surrounded by various halls, including iwans. Some notable examples, only partly preserved, are the caravanserais of Ribat-i Malik (c. 1068–1080) and Ribat-i Sharaf (12th century) in Transoxiana and Khorasan, respectively.[32][25][33]

-

Entrance portal of the Ribat-i Malik caravanserai on the road between Bukhara and Samarkand (c. 1068–1080)

-

Ribat-i Sharaf caravanserai in Khorasan (northeastern Iran), built in 1114–1115

Mausoleums

The Seljuks also continued to build "tower tombs", an Iranian building type from earlier periods, such as the so-called Tughril Tower[b] built in Rayy (south of present-day Tehran) in 1139–1140.[36][37] More innovative, however, was the introduction of mausoleums with a square or polygonal floor plan, which later became a common form of monumental tombs. Early examples of this are the two Kharraqan Mausoleums (1068 and 1093) near Qazvin (northern Iran), which have octagonal forms, and the large Mausoleum of Sanjar (c. 1152) in Merv (present-day Turkmenistan), which has a square base.[36]

-

Kharraqan Towers, a set of mausoleums built in 1068 and 1093 in Iran

-

Tughril Tower in Rayy, south of present-day Tehran (Iran), built in 1139–1140

Materials and decoration

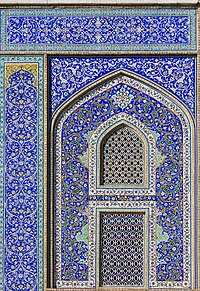

The scarcity of wood on the Iranian Plateau led to the prominence of brick as a construction material, particularly high-quality baked bricks.[38][25] It also encouraged the development and use of vaults and domes to cover buildings, which in turn led to innovations in the methods of structural support for these vaults.[25] The bonding patterns of brickwork were exploited for decorative effect: by combining bricks in different orientations and by alternating between recessed and projecting bricks, different patterns could be achieved. This technique reached its full development during the 11th century. In some cases pieces of glazed tile were inserted into the spaces between bricks to add further color and contrast. The bricks could also be incised with further motifs or to carve inscriptions on the façades of monuments.[25][39]

While brick decoration favoured geometric motifs, stucco or plaster was also used to cover some surfaces and this material could be carved with a wider range of vegetal and floral motifs (arabesques). Tilework and color took on increased importance by the late 12th-century and extensive glazed tile decoration appears in multiple 12th-century monuments. This went in hand with a growing trend towards covering walls and large areas with surface decoration that obscured the structure itself. This trend became more pronounced in later Iranian and Central Asian architecture.[25][39]

The 11th century saw the spread of the muqarnas technique of decoration across the Islamic world, although its exact origins and the manner in which it spread is not fully understood by scholars.[40][41] Muqarnas was used for vaulting and to accomplish transitions between different structural elements, such as the transition between a square chamber and a round dome (squinches).[25] Examples of early muqarnas squinches are found in Iranian and Central Asian monuments during previous centuries, but deliberate and significant use of fully-developed muqarnas is visible in Seljuk structures such as in the additions to the Friday Mosque in Isfahan.[42]

A traditional sign of the Seljuks used in their architecture was an eight-pointed star that held a philosophic significance, being regarded as the symbol of existence and eternal evolution.[dubious – discuss] Many examples of this Seljuk star can be found in tile work, ceramics and rugs from the Seljuk period and the star has even been incorporated in the state emblem of Turkmenistan.[43][44][45][46] Another typical Seljuk symbol is the ten-fold rosette or the large number of different types of rosettes on Seljuk mihrabs and portals that represent the planets which are, according to old central Asian tradition and shamanistic religious beliefs, symbols of the other world. Examples of this symbol can be found in their architecture.[47][verification needed]

See also

Notes

- ^ "Seljuk architecture" can also refer to Anatolian Seljuk architecture, which is largely found in present-day Turkey and is associated with the Sultanate of Rum (late 11th to 13th centuries), ruled by an offshoot of the Seljuk dynasty.

- ^ The tower is traditionally associated with the Seljuk sultan Tughril I (d. 1063), who was buried in the same city, but this connection is apocryphal.[34] If it has any direct connection with a Seljuk sultan, it is most likely with Tughril II (d. 1134).[35]

References

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair S., Sheila, eds. (2009). "Isfahan". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 292–299. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Bosworth, C. E. (1995). "Sald̲j̲ūḳids; III. The various branches of the Sald̲j̲ūḳs; 5. The Sald̲j̲ūḳs of Rūm (ca. 483-707/ca. 1081-1307)". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 948–949. ISBN 978-90-04-09834-3.

- ^ Hattstein & Delius 2011, p. 348.

- ^ Petersen, Andrew (1996). "Seljuks". Dictionary of Islamic architecture. Routledge. pp. 255–256. ISBN 9781134613663.

- ^ Hattstein & Delius 2011, pp. 349–352.

- ^ a b c d e Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Madrasa". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 430–433.

- ^ a b c d e Bosworth, C. E.; Hillenbrand, Robert; Rogers, J. M.; de Blois, F. C. & Darley-Doran, R. E. (1986). "Madrasa". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 1125–1128, 1136–1140. ISBN 978-90-04-07819-2.

- ^ a b c d e Hillenbrand, Robert (1995). "Sald̲j̲ūḳids; VI. Art and architecture; 1. In Persia". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 959–964. ISBN 978-90-04-09834-3.

- ^ a b c d e Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Saljuq". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. pp. 166–168. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Bonner, Jay (2017). Islamic Geometric Patterns: Their Historical Development and Traditional Methods of Construction. Springer. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-4419-0217-7.

- ^ a b Hattstein & Delius 2011, p. 354.

- ^ Bosworth, C. E. (1995). "Sald̲j̲ūḳids; III. The various branches of the Sald̲j̲ūḳs; 1. The Great Sald̲j̲ūḳs of Persia and ʿIrāḳ (429-552/1038-1157)". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 940–943. ISBN 978-90-04-09834-3.

- ^ Hattstein & Delius 2011, pp. 354–359.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 134.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 217.

- ^ Hattstein & Delius 2011, p. 380.

- ^ Peacock 2015, p. 75.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Architecture; V. c. 900–c. 1250; C. Anatolia". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 117–120. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, pp. 234, 264.

- ^ a b c Blair, Sheila; Bloom, Jonathan (2011). "The Friday Mosque at Isfahan". In Hattstein, Markus; Delius, Peter (eds.). Islam: Art and Architecture. h.f.ullmann. pp. 368–369. ISBN 9783848003808.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 140-144.

- ^ a b c O'Kane, Bernard (1995). "Domes". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2024-01-05.

- ^ a b c Tabbaa, Yasser (2007). "Architecture". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Brill. ISBN 9789004161658.

- ^ a b Khaghani, Saeid (2012). Islamic Architecture in Iran: Poststructural Theory and the Architectural History of Iranian Mosques. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-78673-302-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Architecture; V. c. 900–c. 1250; A. Eastern Islamic lands; 2. Iran, c. 1050–c. 1250.". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 92–96. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Grabar, Oleg (1990). The Great Mosque of Isfahan. New York University Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0814730272.

- ^ Saoud 2003, p. 4.

- ^ a b Saoud 2003, p. 7.

- ^ Abaza, Mona; Kéchichian, Joseph A. (2009). "Madrasah". The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Godard 1951.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Iwan". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. p. 337. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 153-154.

- ^ Hattstein & Delius 2011, pp. 363–364.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Rayy". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Canby et al. 2016, pp. 290 and associated footnote on 335.

- ^ a b Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 146.

- ^ Canby et al. 2016, pp. 290 (see also associated footnote on 335).

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 156.

- ^ a b Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 159-161.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 116.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Muqarnas". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 25–28. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 157.

- ^ The Church of Haghia Sophia at Trebizond - David Talbot Rice, Edinburgh University P. for the Russell Trust, 1968

- ^ The Anatolian Civilisations: Seljuk — Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 1983

- ^ Symbolism and Power in Central Asia: Politics of the Spectacular - Sally N. Cummings Routledge,

- ^ Trefoil: Guls, Stars & Gardens: an Exhibition of Early Oriental Carpets, Mills College Art Gallery, January 28-March 11, 1990 - Hillary Dumas, D. G. Dumas

- ^ The Art and Architecture of Turkey, Ekrem Akurgal, Oxford University Press

Bibliography

- Blair, Sheila; Bloom, Jonathan M. (1995). The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250–1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06465-0.

- Blessing, Patricia (2014). Rebuilding Anatolia after the Mongol Conquest: Islamic Architecture in the Lands of Rūm, 1240–1330. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-4724-2406-8.

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila (2009). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- Canby, Sheila R.; Beyazit, Deniz; Rugiadi, Martina; Peacock, A. C. S. (2016). Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-589-4.

- Ettinghausen, Richard; Grabar, Oleg; Jenkins-Madina, Marilyn (2001). Islamic Art and Architecture: 650–1250. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08869-4. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Godard, André (1951). "L'origine de la madrasa, de la mosquée et du caravansérail à quatre īwāns". Ars Islamica (in French). 15/16: 1–9.

- Hattstein, Markus; Delius, Peter, eds. (2011). Islam: Art and Architecture. h.f.ullmann. ISBN 9783848003808.

- Peacock, A. C. S. (2015). Great Seljuk Empire. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-9807-3.

- Saoud, Rabah (2003). Al-Hassani, Salim (ed.). "Muslim Architecture Under Seljuk Patronage (1038-1327)" (PDF). Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation.