HMS Collingwood (1908)

Collingwood at anchor, 1912

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Collingwood |

| Namesake | Vice-Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood, 1st Baron Collingwood |

| Ordered | 26 October 1907 |

| Builder | Devonport Royal Dockyard |

| Laid down | 3 February 1908 |

| Launched | 7 November 1908 |

| Commissioned | 19 April 1910 |

| Fate | Sold for scrap, 12 December 1922 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Class and type | St Vincent-class dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement | 19,700 long tons (20,000 t) (normal) |

| Length | 536 ft (163.4 m) (o/a) |

| Beam | 84 ft 2 in (25.7 m) |

| Draught | 28 ft (8.5 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 4 × shafts; 2 × steam turbine sets |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 6,900 nmi (12,800 km; 7,900 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 758 |

| Armament |

|

| Armour | |

HMS Collingwood was a St Vincent-class dreadnought battleship built for the Royal Navy in the first decade of the 20th century. She spent her whole career assigned to the Home and Grand Fleets and often served as a flagship. Prince Albert (later King George VI) spent several years aboard the ship before and during World War I. At the Battle of Jutland in May 1916, Collingwood was in the middle of the battleline and lightly damaged a German battlecruiser. Other than that battle, and the inconclusive action of 19 August, her service during the war generally consisted of routine patrols and training in the North Sea. The ship was deemed obsolete after the war; she was reduced to reserve and used as a training ship before being sold for scrap in 1922.

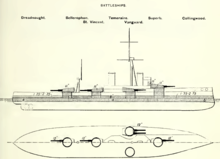

Design and description

The design of the St Vincent class was derived from that of the previous Bellerophon class, with a slight increase in size, armour and more powerful guns, among other more minor changes. Collingwood had an overall length of 536 feet (163.4 m), a beam of 84 feet 2 inches (25.7 m),[1] and a normal draught of 28 feet (8.5 m).[2] She displaced 19,700 long tons (20,000 t) at normal load and 22,800 long tons (23,200 t) at deep load. In 1911 her crew numbered 758 officers and ratings.[3]

Collingwood was powered by two sets of Parsons direct-drive steam turbines, each driving two shafts, using steam from eighteen Yarrow boilers. The turbines were rated at 24,500 shaft horsepower (18,300 kW) and were intended to give the ship a maximum speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). During her full-power, eight-hour sea trials on 17 January 1910, she only reached a top speed of 20.62 knots (38.19 km/h; 23.73 mph) from 26,789 shp (19,977 kW). Collingwood carried enough coal and fuel oil to give her a range of 6,900 nautical miles (12,800 km; 7,900 mi) at a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[4]

Armament and armour

The St Vincent class was equipped with ten breech-loading (BL) 12-inch (305 mm) Mk XI guns in five twin-gun turrets, three along the centreline and the remaining two as wing turrets. The secondary, or anti-torpedo boat, armament comprised twenty BL 4-inch (102 mm) Mk VII guns. Two of these guns were each installed on the roofs of the fore and aft centreline turrets and the wing turrets in unshielded mounts, and the other ten were positioned in the superstructure. All guns were in single mounts.[5][Note 1] The ships were also fitted with three 18-inch (450 mm) torpedo tubes, one on each broadside and the third in the stern.[2]

The St Vincent-class ships had a waterline belt of Krupp cemented armour (KC) that was 10 inches (254 mm) thick between the fore and aftmost barbettes, reducing to a thickness of 2 inches (51 mm) before it reached the ships' ends. Above this was a strake of armour 8 inches (203 mm) thick. Transverse bulkheads 5 and 8 inches (127 and 203 mm) inches thick terminated the thickest parts of the waterline and upper armour belts once they reached the outer portions of the endmost barbettes.[8]

The three centreline barbettes were protected by armour 9 inches (229 mm) thick above the main deck that thinned to 5 inches (127 mm) below it. The wing barbettes were similar except that they had 10 inches of armour on their outer faces. The gun turrets had 11-inch (279 mm) faces and sides with 3-inch (76 mm) roofs. The three armoured decks ranged in thicknesses from .75 to 3 inches (19 to 76 mm). The front and sides of the forward conning tower were protected by 11-inch plates, although the rear and roof were 8 inches and 3 inches thick, respectively.[9]

Alterations

The guns on the forward turret roof were removed in 1911–1912 and the upper forward pair of guns in the superstructure were removed in 1913–1914. In addition, gun shields were fitted to all guns in the superstructure and the bridge structure was enlarged around the base of the forward tripod mast. During the first year of the war, a fire-control director was installed high on the forward tripod mast. Around the same time, the base of the forward superstructure was rebuilt to house eight 4-inch guns and the turret-top guns were removed, which reduced her secondary armament to a total of fourteen guns. In addition, a pair of 3-inch anti-aircraft (AA) guns were added.[10]

By April 1917, Collingwood mounted thirteen 4-inch anti-torpedo boat guns as well as single 4-inch and 3-inch AA guns. Approximately 50 long tons (51 t) of additional deck armour had been added after the Battle of Jutland. Before the end of the war the AA guns were moved from the deckhouse between the aft turrets to the stern and the stern torpedo tube was removed. In 1918, a high-angle rangefinder was fitted and flying-off platforms were installed on the roofs of the fore and aft turrets.[10]

Construction and career

Collingwood, named after Vice-Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood,[11] was ordered on 26 October 1907.[12] She was laid down at Devonport Royal Dockyard on 3 February 1908, launched on 7 November 1908 and completed in April 1910. Including her armament, the ship's cost is quoted at £1,680,888[3] or £1,731,640.[5]

On 19 April 1910, Collingwood was commissioned and assigned to the 1st Division of the Home Fleet under the command of Captain William Pakenham.[13] She joined other members of the fleet in regular peacetime exercises, and on 11 February 1911 damaged her bottom plating on an uncharted rock off Ferrol. On 24 June the ship was present at the Coronation Fleet Review for King George V at Spithead.[12] Pakenham was relieved by Captain Charles Vaughan-Lee on 1 December.[13] On 1 May 1912, the 1st Division was renamed the 1st Battle Squadron.[12] On 22 June, Vaughan-Lee was transferred to the battleship Bellerophon and Captain James Ley assumed command; Vice-Admiral Stanley Colville hoisted his flag in Collingwood as commander of the 1st Battle Squadron.[13] The ship participated in the Parliamentary Naval Review on 9 July at Spithead before beginning a refit late in the year. In March 1913, Collingwood and the 1st Battle Squadron undertook a port visit to Cherbourg, France.[14] Midshipman Prince Albert (later King George VI) was assigned to the ship on 15 September 1913.[15] Collingwood hosted Albert's older brother, Edward, Prince of Wales, during a short cruise on 18 April 1914. She became a private ship when Colville hauled down his flag on 22 June.[14]

World War I

Between 17 and 20 July 1914, Collingwood took part in a test mobilisation and fleet review as part of the British response to the July Crisis. Arriving in Portland on 27 July, she was ordered to proceed with the rest of the Home Fleet to Scapa Flow two days later[14] to safeguard the fleet from a possible German surprise attack.[16] In August 1914, following the outbreak of World War I, the Home Fleet was reorganised as the Grand Fleet, and placed under the command of Admiral John Jellicoe.[17] Most of it was briefly based (22 October to 3 November) at Lough Swilly, Ireland, while the defences at Scapa were strengthened. On the evening of 22 November 1914, the Grand Fleet conducted a fruitless sweep in the southern half of the North Sea; Collingwood stood with the main body in support of Vice-Admiral David Beatty's 1st Battlecruiser Squadron. The fleet was back in port in Scapa Flow by 27 November.[18] The 1st Battle Squadron cruised north-west of the Shetland Islands and conducted gunnery practice on 8–12 December. Four days later, the Grand Fleet sortied during the German raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby, but failed to make contact with the High Seas Fleet. Collingwood and the rest of the Grand Fleet conducted another sweep of the North Sea on 25–27 December.[19]

The Grand Fleet, including Collingwood, conducted gunnery drills on 10–13 January 1915 west of Orkney and Shetland. On the evening of 23 January, the bulk of the Grand Fleet sailed in support of Beatty's battlecruisers, but Collingwood and the rest of the fleet did not participate in the ensuing Battle of Dogger Bank the following day.[20] The ship sailed for Portsmouth Royal Dockyard on 2 February to begin a brief refit and returned on 18 February.[21] On 7–10 March, the Grand Fleet conducted a sweep in the northern North Sea, during which it conducted training manoeuvres. Another such cruise took place on 16–19 March.[22] From 25 March to 14 April 1915, Rear-Admiral Hugh Evan-Thomas temporarily hoisted his flag aboard Collingwood.[23] On 11 April, the Grand Fleet conducted a patrol in the central North Sea and returned to port on 14 April; another patrol in the area took place on 17–19 April, followed by gunnery drills off Shetland on 20–21 April.[24]

The Grand Fleet conducted sweeps into the central North Sea on 17–19 May and 29–31 May without encountering any German vessels. During 11–14 June the fleet conducted gunnery practice and battle exercises west of Shetland.[25] Collingwood was briefly docked at Invergordon from 23 to 25 June. King George V inspected the ship on 8 July,[23] and the Grand Fleet conducted training off Shetland beginning three days later.[26] Rear-Admiral Ernest Gaunt temporarily used Collingwood as his flagship from 24 August to 24 September and from 10 December to 16 January 1916.[27] On 2–5 September 1915, the fleet went on another cruise in the northern end of the North Sea and conducted gunnery drills. Throughout the rest of the month, the Grand Fleet conducted numerous training exercises. The ship, together with the majority of the Grand Fleet, conducted another sweep into the North Sea from 13 to 15 October. Almost three weeks later, Collingwood participated in another fleet training operation west of Orkney during 2–5 November.[28] On 21 November, she sailed for Devonport Royal Dockyard for a minor overhaul and arrived back at Scapa on 9 December.[29]

The Grand Fleet departed for a cruise in the North Sea on 26 February 1916; Jellicoe had intended to use the Harwich Force to sweep the Heligoland Bight, but bad weather prevented operations in the southern North Sea. As a result, the operation was confined to the northern end of the sea. Another sweep began on 6 March, but had to be abandoned the following day as the weather grew too severe for the escorting destroyers. On the night of 25 March, Collingwood and the rest of the fleet sailed from Scapa Flow to support Beatty's battlecruisers and other light forces raiding the German Zeppelin base at Tondern. By the time the Grand Fleet approached the area on 26 March, the British and German forces had already disengaged and a strong gale threatened the light craft, so the fleet was ordered to return to base. On 21 April, the Grand Fleet conducted a demonstration off Horns Reef to distract the Germans while the Russian Navy relaid its defensive minefields in the Baltic Sea. The fleet returned to Scapa Flow on 24 April and refuelled before proceeding south in response to intelligence reports that the Germans were about to launch a raid on Lowestoft. The Grand Fleet arrived in the area after the Germans had withdrawn. On 2–4 May, the fleet conducted another demonstration off Horns Reef to keep German attention focused on the North Sea.[30]

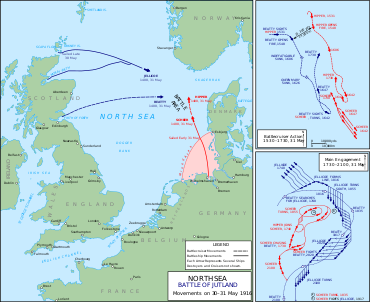

Battle of Jutland

In an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the German High Seas Fleet, composed of 16 dreadnoughts, 6 pre-dreadnoughts, 6 light cruisers, and 31 torpedo boats, departed the Jade Bight early on the morning of 31 May. The fleet sailed in concert with Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper's five battlecruisers and supporting cruisers and torpedo boats. The Royal Navy's Room 40 had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans of the operation. In response, the Admiralty ordered the Grand Fleet, totalling some 28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers, to sortie the night before to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet.[31] Collingwood was the eighteenth ship from the head of the battle line after the Grand Fleet deployed for battle.[14]

The initial action was fought primarily by the British and German battlecruiser formations in the afternoon, but by 18:00,[Note 2] the Grand Fleet approached the scene. Fifteen minutes later, Jellicoe gave the order to turn and deploy the fleet for action. The transition from cruising formation caused congestion with the rear divisions, forcing many ships to reduce speed to 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) to avoid colliding with each other. During the first stage of the general engagement, Collingwood fired eight salvos from her main guns at the crippled light cruiser SMS Wiesbaden from 18:32, although the number of hits made, if any, is unknown. Her secondary armament then engaged the destroyer SMS G42, which was attempting to come to Wiesbaden's assistance, but failed to hit her. At 19:15 Collingwood fired two salvoes of high explosive (HE) shells at the battlecruiser SMS Derfflinger, hitting her target once before she disappeared into the mist. The shell detonated in the German ship's sickbay and damaged the surrounding superstructure. Shortly afterwards, during the attack of the German destroyers around 19:20, the ship fired her main armament at a damaged destroyer without success and dodged two torpedoes that missed by 10 yards (9.1 m) behind and 30 yards (27 m) in front. This was the last time she fired her guns during the battle.[32]

Following the German destroyer attack, the High Seas Fleet disengaged, and Collingwood and the rest of the Grand Fleet saw no further action in the battle. This was, in part, due to confusion aboard the fleet flagship over the exact location and course of the German fleet; without this information, Jellicoe could not bring his fleet to action. At 21:30, the Grand Fleet began to reorganise into its night-time cruising formation. Early on the morning of 1 June, the Grand Fleet combed the area, looking for damaged German ships, but after spending several hours searching, they found none. Collingwood fired a total of 52 armour-piercing, capped and 32 HE shells from her main armament and 35 four-inch shells during the battle.[33] Prince Albert was a sub-lieutenant commanding the forward turret during the battle and sat in the open on the turret roof during a lull in the action.[34]

Subsequent activity

After the battle the ship was transferred to the 4th Battle Squadron under the command of Vice-Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee, who inspected Collingwood on 8 August 1916.[35] The Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August to ambush the High Seas Fleet while it advanced into the southern North Sea, but a series of miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German U-boats during the operation, prompting Jellicoe to decide to not risk the major units of the fleet south of 55° 30' North due to the prevalence of German submarines and mines. The Admiralty concurred and stipulated that the Grand Fleet would not sortie unless the German fleet was attempting an invasion of Britain or there was a strong possibility it could be forced into an engagement under suitable conditions.[36]

Collingwood received a brief refit at Rosyth in early September before rejoining the Grand Fleet. On 29 October Sturdee came aboard to present the ship with her battle honour, "Jutland 1916". Captain Wilmot Nicholson briefly assumed command on 1 December before transferring to the new battlecruiser Glorious upon his relief by Captain Cole Fowler on 26 March 1917. Together with the rest of the 4th Battle Squadron, Collingwood put to sea for tactical exercises for a few days in February 1917. The ship was present at Scapa Flow when her sister ship Vanguard's magazines exploded on 9 July and her crew recovered the bodies of three men killed in the explosion. In January 1918, Collingwood and other of the older dreadnoughts cruised off the coast of Norway for several days, possibly to provide distant cover for a convoy to Norway.[37] Along with the rest of the Grand Fleet, she sortied on the afternoon of 23 April after radio transmissions revealed that the High Seas Fleet was at sea after a failed attempt to intercept the regular British convoy to Norway. The Germans were too far ahead of the British, and no shots were fired.[38] By early November, Collingwood was at Invergordon to receive a brief refit in the floating dock based there, and missed the surrender of the High Seas Fleet on the 21st. She was slightly damaged on 23 November while attempting to come alongside the oiler RFA Ebonol.[39]

In January 1919, Collingwood was transferred to Devonport and assigned to the Reserve Fleet. Upon the dissolution of the Grand Fleet on 18 March, the Reserve Fleet was redesignated the Third Fleet and Collingwood became its flagship. She became a tender to HMS Vivid on 1 October and served as a gunnery and wireless telegraphy (W/T) training ship. The W/T school was transferred to Glorious on 1 June 1920 and the gunnery duties followed in early August; Collingwood returned to the reserve. She became a boys' training ship on 22 September 1921 until she was paid off on 31 March 1922. Collingwood was sold to John Cashmore Ltd for scrap on 12 December and arrived at Newport, Wales, on 3 March 1923 to be broken up.[39]

Relics

Battle ensigns flown by the ship during Jutland survive at the shore establishment of the same name and at the Roedean School in East Sussex.[40]

Footnotes

- ^ Sources disagree on the number, type and composition of the secondary armament. Burt gives only eighteen 4-inch guns and claims that they were the older quick-firing QF Mark III guns. In addition, he lists a 12-pounder (three-inch (76 mm)) gun.[3] Preston concurs on the number of 4 inchers, but does not list the 12 pounder.[2] Parkes says twenty 4-inch guns; while not identifying the type, he does say that they were 50-calibre guns[5] and Preston agrees.[6] Friedman shows the QF Mark III as a 40-calibre gun and states that the 50-calibre BL Mark VII gun armed all of the early dreadnoughts.[7]

- ^ The times used in this section are in UT, one hour behind CET, which is often used in German works.

Citations

- ^ Burt, pp. 75–76

- ^ a b c Preston 1972, p. 125

- ^ a b c Burt, p. 76

- ^ Burt, pp. 76, 80

- ^ a b c Parkes, p. 503

- ^ Preston 1985, p. 23

- ^ Friedman, pp. 97–98

- ^ Burt, pp. 76, 78; Parkes, p. 503

- ^ Burt, pp. 76, 78; Parkes, p. 504

- ^ a b Burt, p. 81

- ^ Silverstone, p. 223

- ^ a b c Burt, p. 86

- ^ a b c Brady, Part One, p. 29

- ^ a b c d Burt, p. 88

- ^ Judd, p. 28

- ^ Massie, pp. 15–20

- ^ Preston 1985, p. 32

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 163–165

- ^ Brady, Part One, p. 32; Jellicoe, pp. 172, 179, 183–184

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 190, 194–196

- ^ Brady, Part One, p. 32

- ^ Jellicoe, p. 206

- ^ a b Brady, Part One, p. 33

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 211–212

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 217, 218–219, 221–222

- ^ Jellicoe, p. 228

- ^ Brady, Part One, pp. 33–34

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 243, 246, 250, 253

- ^ Brady, Part One, p. 34

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 271, 275, 279–280, 284, 286–290

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 54–55, 57–58

- ^ Campbell, pp. 37, 116, 146, 157, 205, 208, 212, 214, 229–230

- ^ Campbell, pp. 256, 274, 309–310, 346, 348, 358

- ^ Gordon, pp. 454, 459

- ^ Brady, Part Two, p. 19

- ^ Halpern, pp. 330–332

- ^ Brady, Part Two, pp. 19–22

- ^ Massie, p. 748

- ^ a b Brady, Part Two, pp. 23–24

- ^ Gordon, p. 417

Bibliography

- Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-863-8.

- Brady, Mark (May 2014). "HMS Collingwood War Record, Part One". Warship (176). London: World Ship Society: 29–35. ISSN 0966-6958.

- Brady, Mark (September 2014). "HMS Collingwood War Record, Part Two". Warship (177). London: World Ship Society: 19–24. ISSN 0966-6958.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-324-5.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Gordon, Andrew (2012). The Rules of the Game: Jutland and British Naval Command. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-336-9.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Jellicoe, John (1919). The Grand Fleet, 1914–1916: Its Creation, Development, and Work. New York: George H. Doran Company. OCLC 13614571.

- Judd, Denis (1982). King George VI: 1895–1952. London: Michael Joseph. ISBN 0-7181-2184-8.

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-45671-6.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990) [1966]. British Battleships, Warrior 1860 to Vanguard 1950: A History of Design, Construction, and Armament (New & rev. ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations 1914–1918. New York: Galahad Books. ISBN 0-88365-300-1.

- Preston, Antony (1985). "Great Britain and Empire Forces". In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 1–104. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-917-8.