Historiography of the Suffragettes

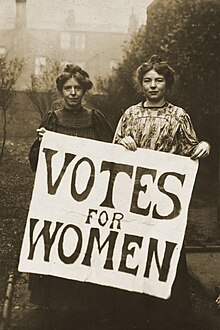

The Historiography of the Suffragette Campaign deals with the various ways Suffragettes are depicted, analysed and debated within historical accounts of their role in the campaign for women's suffrage in early 20th century Britain.

The term “Suffragette” refers specifically to British suffragists who campaigned for the rights of women to vote in public elections as part of militant organisations, such as the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).[1] These organisations were formed under the belief that existing legal and constitutional campaigning had achieved little towards the success of the women's suffrage campaign in Britain, and more drastic measures were needed.[2][3][4] Suffragettes, under the motto of “Deeds, Not Words”, engaged in civil disobedience and disruption, smashing windows, exploding letterboxes, cutting telegraph wires and storming parliament in an attempt to oversee the success of their cause.

Although female enfranchisement was granted with the Representation of the People Acts of 1918 and 1928, the militant campaigning methods of Suffragettes have become a source of contention amongst historical accounts. The debate primarily centres around whether militancy was a justified, effective and decisive means to a failing political end, or acted as a hindrance to the ongoing constitutional campaigning of other suffragists by alienating politicians and the British public. There are four main schools of Suffragette history, each taking a different position on the perceived efficacy, or lack thereof, of Suffragettes.

The Militant School

The Militant school is one of two founding schools of Suffragette history, established within the accounts and autobiographies of WSPU members, who supported and engaged in militancy themselves. Accounts of the Militant school focus on a dichotomous organisation of suffragists as either militants or non-militants, presenting Suffragettes as necessary and effective saviours to a failing political cause, and justifying militancy by arguing that without it, female enfranchisement would not have been achieved when it was.[5]

When the WSPU was formed, it focused on a complete break from the constitutionalist campaigning that had emerged in the 19th century and continued with the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) into the 20th century. Constitutionalists believed that social change would be instigated by “the gradual and progressive evolution of a society through its own organic capacity for developments and growth”, or that with minimal campaigning, society would evolve of its own accord and grant women the vote.[5] The WSPU disputed this; Emmeline Pankhurst's ‘Freedom or Death’ speech of 1913 revealed her view that constitutional methods had been ineffective in gaining enfranchisement in a male-centred and male-dominated political environment.[6] The Suffragette motto, ‘Deeds, Not Words’, was therefore implemented to take what Suffragettes argued was a stronger force of social action; and it is this position accounts of the Militant school present.[citation needed]

Within their respective autobiographies My Own Story and Unshackled, Suffragettes and WSPU founders Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst both justify the decision to adopt militancy with the breakaway of the WSPU as a direct response to the perceived lack of progress of the non-militant NUWSS, to which they had both previously belonged.[2][3] Both accounts express belief that non-militants had achieved little with constitutional lobbying, and that militancy was thus a necessity if the campaign was to be successful. As Emmeline Pankhurst wrote, the value of militant actions held an “innumerable value” that constitutionalist campaigning could not match.[7] Central to the militant account of Emmeline Pankhurst is also the argument that the militancy of Suffragettes was justified as the same means through which men had procured their own enfranchisement in Britain previously.[8][9] The Militant school posits that militancy and suffrage historically go hand in hand, and therefore militancy was a justified, historically proven means to an end.[5]

As well as justifying the actions of Suffragettes, the Militant school also posits that it was Suffragettes alone who ensured the success of the Suffrage campaign. Suffragette Annie Kenney said that at the time of the militant split, there was “no living interest in the question” of votes for women amongst the British public, rendering the campaign stagnant.[10] Suffragette Mona Caird wrote that constitutional campaigning provided no evidence in the eyes of the public and politicians that women wanted the vote, but Suffragettes and the militant campaign amended this by placing the campaign within practical politics.[11] Ultimately, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence of the Militant school argued it was only the actions of Suffragettes which “shook the complacency of the government” adequately enough to spur any action, to the extent that it was unlikely the vote would have been granted at all were it not for their militant campaign.[12]

The Militant school thus posits that without militancy, female enfranchisement in Britain would not have been achieved when it was, and that Suffragettes were justified in their actions as those responsible for the passing of female enfranchisement within British parliament where their constitutionalist counterparts had failed.[citation needed]

The Constitutionalist School

The Constitutionalist School is the second founding school of Suffragette history, established within the accounts of constitutionalist suffragists such as those belonging to the NUWSS. Accounts of the constitutionalist school come from those suffragists who engaged in traditional and lawful campaigning, and disapproved of militancy and Suffragettes as a hindrance to their own efforts.[citation needed]

The most widely regarded constitutionalist work is The Cause by NUWSS member Ray Strachey. The NUWSS held a “strong disapprobation of the use of physical force and physical violence” as a means to a political end; constitutionalist accounts such as Strachey's therefore stand directly at odds with the accounts of the Militant school, and established the initial historical debate surrounding the actions of Suffragettes.[5]

Within The Cause, Strachey presents Suffragettes as inferior to constitutional suffragists through a dichotomous distinction between the “organised, powerful and politically important” NUWSS, compared to the “defiant and antagonistic” WSPU.[13] She writes that militants displayed a “lack of dignity” and held “extraordinary notoriety”, which was directly rousing public protests and had “no favourable effect” on the campaign by antagonising the government.[14][1] Much focus is therefore placed on how militancy alienated the British public by making the campaign appear “absurd”, and presenting women as too emotional and irrational to participate in politics.[15]

Suffragette historian Paula Bartley also presents a constitutionalist analysis in her account of the actions of Suffragettes. She writes that militancy undermined Suffragist efforts to present women as “mature adults” who were worthy of the vote, instead making the whole campaign appear irrational.[16] This, she writes, provided the “ideal excuse” for the government at the time to continue to deny female suffrage.[16] Indeed, Winston Churchill wrote in a letter to Christabel Pankhurst, cited within constitutionalist accounts, that his attitude of “growing sympathy” towards female enfranchisement was undermined by the actions of Suffragettes, who had alienated his support with their militant campaigning.[17]

At odds with the Militant school's depiction of Suffragettes, the Constitutionalist school posits that constitutional suffragists were on the way to success in gaining female enfranchisement, and had politicians and the public on side, before militancy hindered any further support and even caused discouragement and alienation among those who had previously supported the cause. The historiographical debate thus emerged between these two schools as to whether Suffragettes were to be credited with the success of women's suffrage in Britain, or credited with delaying it.

The Masculinist School

The Masculinist school of Suffragette history emerged in the decades following the Militant and Constitutionalist schools, with George Dangerfield's The Strange Death of Liberal England as the foundational work. The Masculinist school is so-titled by Suffragette historian Sandra Stanley Holton because it is a male-constructed addition to the historiography of Suffragettes, depicting them as a women's political movement that was, by its existence, an aberration from traditional male politics which would have by itself overseen the granting of female enfranchisement.[5]

The Masculinist school's analysis of Suffragettes focuses on blaming them for the failure of successive liberal governments to grant women the vote, due to their militant activities. Dangerfield writes militancy was seen as “neither sensible nor endearing” to the public, and as a result, the sympathy of both politicians and the public to the suffragist cause “ebbed away” and the granting of female enfranchisement was significantly delayed.[18][19]

He also describes Suffragettes as “ludicrous” and “melodramatic”, and describes their militant campaign as a “brutal comedy” which invited “unprincipled laughter” amongst parliament and the public, sharing the Constitutionalist view that militancy caused women to be seen as unworthy and undeserving of the vote compared to their male counterparts.[18]

Walter L. Arnstein similarly attributed Suffragettes as hindrances to their own efforts, writing “the law-minded prime minister” David Lloyd George was, “understandably enough, not attracted to a cause whose adherents vilified him” through militant attacks.[20] Brian Harrison also blames militancy for the refusal of the liberal government to enfranchise women, as he claims favourable public opinion was instrumental to the success of the movement, but the disruption and violence of Suffragettes and their militancy only created public opposition, and perpetuated the view that women were too emotional and could not think logically enough to vote.[21]

The Masculinist school does depict Suffragettes as justified in their belief that women were deserving of the vote, and does not deny support for female enfranchisement.[18] However, defining the Masculinist school is also the view that women would have been granted this right eventually as the “vehicles of the inevitable historical processes that were the political actions of men”.[22] Suffragettes and their actions are argued to have delayed what Masculinist's propose was a natural and already underway progression towards female enfranchisement. Masculinist histories thus posit that in taking actions into their own hands, Suffragettes delayed a historically inevitable process, as their actions alienated public and political opinion to too large an extent to be considered useful.[22]

Contemporary Feminist Schools

Developing later in the 20th century were the new-feminist schools of suffrage history, influenced by the emergence of radical feminist historians, whose ideology encompassed second-wave feminism and whose construction of history was focused on subverting the marginalisation of women in the historical record.[citation needed]

Contemporary Feminist schools tend not to side with either the Militant, Constitutionalist or Masculinist Schools on the historical debate surrounding Suffragettes’ contributions to the enfranchisement movement, but rather focus on an evaluation of the position of each amongst a broader discussion of the historical and social implications of the Suffragette's actions. Some Contemporary Feminist Schools also focus on shifting Suffragette history away from the hindrance-or-help debate, and thus do not participate at all in the historical debate.[citation needed]

The Radical feminist school does engage in this debate. Central to this analysis is the argument that women's liberation required a total restructuring of society, and militancy was and continues to be a means to achieve this. In terms of Suffragette history, this gave rise to the argument that militancy was necessary and effective not just as a political tactic, but as a significant symbol of wider female emancipation and societal change.[23]

June Purvis claimed that the widely held academic and historical focus on militancy shows little understanding of what the enfranchisement movement actually meant, due to its focus on the effects of militancy, rather than the causes.[23] She claims the causes of militancy were born from “a sense of the burning injustice of the wrongs done to [females] in a male-dominated society”, and thus that militancy was an “unavoidable adaptation of the masculine justification of force”.[24][23] She depicts militancy as justified within its context, as a tactic previously adopted by male suffragists, and analyses it as a mark of wider female emancipation, subverting traditional activities of women in the political sphere.[23] From a radical feminist view, militancy was not simply a radical political tactic undertaken purely to win the vote, but ran much deeper as a “repudiation of submissiveness”, as women felt it necessary to subvert their traditional roles in society to not only win the vote but to achieve wider emancipation.[23] The Radical feminist school therefore interprets militancy as much more than just the effective or ineffective political tactics examined in militant, constitutionalist and masculinist schools, and instead depicts Suffragettes as spurring a movement that inspired greater female emancipation and societal change on a much broader scale.[citation needed]

In regards to the debate surrounding the efficacy, or lack thereof, of Suffragettes, consensus amongst Contemporary Feminist schools is that neither Suffragettes nor their constitutionalist counterparts can be credited with standalone success in the achievement of female enfranchisement. Rather, it is argued that constitutionalists gained political confidence from the radical actions of Suffragettes, and were able to exploit the public awareness militancy raised, positive or not, to further their cause.[5][16] Contemporary Feminist Schools therefore posit that whether a hindrance or a help to broader Suffragist efforts, Suffragettes were a necessary part of the granting of female enfranchisement within Britain.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ a b Strachey, Ray (1989). The cause : a short history of the women's movement in Great Britain. Virago. p. 302. ISBN 0860680428. OCLC 422124406.

- ^ a b Pankhurst, Christabel, Dame, 1880-1958. (1987). Unshackled : the story of how we won the vote. The Cresset Library. ISBN 0091728851. OCLC 317340141.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Pankhurst, Emmeline (28 June 2018). My Own Story. Random House. p. 193. ISBN 9781473559561. OCLC 1032198296.

- ^ Purvis, June (2016). Emmeline Pankhurst : A biography. Routledge. ISBN 9780203358528. OCLC 1007223040.

- ^ a b c d e f Purvis, June; Holton, Sandra (2016). Votes for Women. Routledge. pp. 13–33. ISBN 9780203006443. OCLC 1007230572.

- ^ Pankhurst, Emmeline (27 April 2007). "Great speeches of the 20th century: Emmeline Pankhurst's Freedom or death". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ^ Pankhurst, Emmeline (28 June 2018). My own story. Random House. p. 56. ISBN 9781473559561. OCLC 1032198296.

- ^ Pankhurst, Emmeline (28 June 2018). My own story. Random House. p. 55. ISBN 9781473559561. OCLC 1032198296.

- ^ Purvis, June; Holton, Sandra (2016). Votes for Women. Routledge. p. 16. ISBN 9780203006443. OCLC 1007230572.

- ^ Kenney, Annie (1924). Memories of a Militant. London: Edward Arnold and Co. p. 295.

- ^ "Caird, Mona, "Militant Tactics and Woman's Suffrage", Westminster Review 170, no. 5 (1908): 526".

- ^ Pethick-Lawrence, Frederick William Peth. (2010). Women's fight for the vote. Nabu Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-1177105033. OCLC 944531756.

- ^ Strachey, Ray, 1887-1940. (1989). The cause : a short history of the women's movement in Great Britain. Virago. pp. 309–310. ISBN 0860680428. OCLC 422124406.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Strachey, Ray, 1887-1940. (1989). The cause : a short history of the women's movement in Great Britain. Virago. p. 310. ISBN 0860680428. OCLC 422124406.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Strachey, Ray, 1887-1940. (1989). The cause : a short history of the women's movement in Great Britain. Virago. p. 309. ISBN 0860680428. OCLC 422124406.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Bartley, Paula (12 November 2012). Emmeline Pankhurst. doi:10.4324/9780203354872. ISBN 9780203354872.

- ^ Strachey, Ray, 1887-1940. (1989). The cause : a short history of the women's movement in Great Britain. Virago. p. 259. ISBN 0860680428. OCLC 422124406.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Dangerfield, George (4 September 2017). The Strange Death of Liberal England : 1910-1914. p. 140. ISBN 9781351473255. OCLC 1003866262.

- ^ Dangerfield, George (4 September 2017). The Strange Death of Liberal England : 1910-1914. p. 155. ISBN 9781351473255. OCLC 1003866262.

- ^ Arnstein, Walter L. (1968). Votes for women : myths and reality : a study of the movement for 'female emancipation' from the 1860s until 1918. History Today. OCLC 779070852.

- ^ Harrison, Brian (2016). Separate Spheres : The Opposition to Women's Suffrage in Britain. Routledge. ISBN 9780203104088. OCLC 1007223758.

- ^ a b Dangerfield, George (4 September 2017). The Strange Death of Liberal England : 1910-1914. Routledge. p. 152. ISBN 9781351473255. OCLC 1003866262.

- ^ a b c d e f Purvis, June, June; Holton, Sandra (2016). Votes for Women. Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 9780203006443. OCLC 1007230572.

- ^ Purvis, June (2016). Emmeline Pankhurst : A biography. Routledge. p. 360. ISBN 9780203358528. OCLC 1007223040.