History of Saint Kitts and Nevis

Saint Kitts and Nevis have one of the longest written histories in the Caribbean, both islands being among Spain's and England's first colonies in the archipelago. Despite being only two miles apart and quite diminutive in size, Saint Kitts and Nevis were widely recognized as being separate entities with distinct identities until they were forcibly united in the late 19th century.

Pre-Columbian Period (2900 BC – 1493 AD)

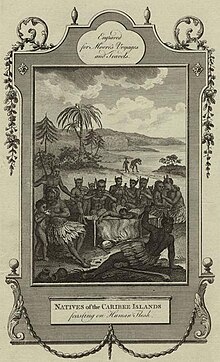

The first natives to live on the islands, as early as 3,000 years ago, were called Ciboney. However, the lack of pottery makes their origin and timeline uncertain. They were followed by the Arawak peoples, or Taino in 800 AD.

The warlike Island Caribs followed and had expanded north of St. Kitts by the time of the Spanish conquest. Peak native populations occurred between 500 and 600 AD.[1]

The First Europeans (1493–1623)

The first Europeans to see and name the islands were the Spanish under Christopher Columbus, who sighted the islands on 11 and 13 November 1493 during his second voyage. He named Saint Kitts San Jorge (Saint George) and Nevis San Martin (sighted on Saint Martin's Day). By 1540, Nieves was used by the Spanish, an abbreviation of Santa Maria de las Nieves, a reference to its cloud cover resembling snow.[1]: 13 [2]

Privateer Francis Drake mentions visiting Saint Christophers Island in 1585 during Christmas.[1]: 13

The next European encounter occurred in June 1603, when Bartholomew Gilbert gathered Lignum vitae on Nevis before stopping at St. Kitts. In 1607, Captain John Smith stopped at Nevis for five days on his way to founding the first successful settlement in Virginia. Smith documented the many hot springs in Nevis, whose waters had remarkable curative abilities against skin ailments and bad health. Robert Harcourt stopped at Nevis in 1608.[2]: 20–23

Saint Kitts and Nevis (1623–1700)

In 1620, Ralph Merifield and Sir Thomas Warner received from King James I, a Royal Patent to colonize the Leeward Islands, but with overall authority through James Hay, 1st Earl of Carlisle. Merifield and Warner formed the company Merwars Hope, which was renamed Society of Adventurers, which merged into the Royal African Company in 1664. Warner arrived on St. Kitts on 7 February 1624 (N.S., "28 January 1623" or 1623/4 O.S.;[3] with 15 settlers and came to terms with the Carib Chief Ouboutou Tegremante. Three Frenchmen were already on the island, either Huguenot refugees, pirates, or castaways. The Hurricane of September 1623 wiped out their tobacco and vegetable crop, yet the colony survived and grew. Hopewell arrived in 1624, and included Warner's friend Colonel John Jaeffreson, who built Wingfield Manor. This Jaeffreson may have been an ancestor of Thomas Jefferson's.[1]: 14–16 [4]

In 1625, a French captain, Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc, arrived on St. Kitts aboard his 14-gun brigantine and a crew of 40. He had escaped a three-hour battle with a 35-gun Spanish warship near the Cayman Islands. In 1627, Warner and d'Esnambuc split the island in four quarters, with the English controlling the middle half and the French the end quarters. Cardinal Richelieu formed the Compagnie de Saint-Christophe in 1626, and 40 slaves were purchased from Senegal. By 1635, the number of slaves on St. Kitts had grown to 500–600, and by 1665 the French West India Company replaced the Compagnie.[1]: 21–22

As the European population on Saint Kitts continued to increase, Chief Tegremond grew hostile to the foreigners in 1626, and plotted their elimination with the help of other Island Caribs. However, a native woman named Barbe informed Warner and d'Esnambuc of the plot and they decided to take action. The Europeans acted by getting the Indians intoxicated at a party before returning to their village, where 120 were killed in their sleep. The following day, at a site now called Bloody Point, with a ravine known as Bloody River, over 2,000 Caribs were massacred. By 1640, the remaining Caribs not enslaved on St. Kitts, Nevis, and Antigua, were removed to Dominica.[1]: 17–18

In 1628, Warner allowed Anthony Hilton to settle Nevis, along with 80 others from St. Kitts. Hilton had recently escaped murder by his indentured servant, and decided to sell his St. Kitts' plantation. Hilton's 80 were joined by 100 other settlers, originally bound for Barbuda.[2]: 40–41

The 1629 English colonization was led by George Donne.[5] Both powers then proceeded to colonise neighbouring islands from their bases. The English settled Nevis (1628), Antigua (1632), Montserrat (1632) and later Anguilla (1650) and Tortola (1672). The French colonised Martinique (1635), the Guadeloupe archipelago (1635), St Martin (1648), St Barths (1648), and Saint Croix (1650).

Saint Kitts and Nevis suffered heavily from a Spanish raid in 1629, led by Fadrique de Toledo, 1st Marquis of Villanueva de Valdueza. All settlements were destroyed, nine hostages taken back to Spain, and 600 men taken to work the mines in Spanish America. Four ships were supposed to carry the rest back to England, but they returned to the islands soon after the Spanish departed. This was the only Spanish attempt to keep the English and French out of the Leeward Islands.[1]: 19–23

During the Battle of the Fig Tree in 1635, the French forcefully removed English settlers who had encroached into the French portion of St. Kitts. The French used 250 armed slaves in the conflict.[1]: 34

The islands' earliest cash crop was tobacco, along with ginger and indigo dye. However, production from the Caribbean and North American colonies deflated the price resulting in an 18-month moratorium on St. Kitts tobacco farming in 1639. This prompted the production of sugar from sugar cane on St. Kitts in 1643, and on Nevis in 1648. Windmills were built to crush the canes and extract the juice. The planters grew prosperous and even rich, where Nevis became the richest British colony in the western hemisphere by 1652. By 1776, St. Kitts was the richest British colony per capita. Though indentured servants were common amongst the islands, fewer than half survived their servitude, and field work required African slaves. There were twice the number of slaves to Europeans on St. Kitts by the end of the 17th century. In 1675, the population on Nevis was about 8,000, half black. By 1780, the Nevis population had grown to 10,000, 90% black. The slaves had very harsh living and working conditions, only lasting eight to twelve years in the fields, and by the 18th century, two-fifths died within a year of arrival. About 22% died on the Middle Passage.[1]: 26–31 [2]: 78–79

With the death of d'Esnambuc in 1635, Phillippe de Longvilliers de Poincy became Lieutenant General of the Isles of America and Captain-General of St. Christopher on 20 February 1639. The King of France had sold the French portion of the island to the Order of Saint John. Dissatisfied with the independence of de Poincy, the King of France sent Noel de Patrocles de Thoisy to replace him. However, De Thoisy was repulsed, captured and sent back to France, along with his allies the Capuchin monks. De Poincy started construction of his Château de la Montagne in 1642, where he resided until his death in 1650. He was succeeded by Governor de Sales.[1]: 34–35

In 1652, Prince Rupert's squadron visited Nevis and exchanged fire with the Pelican Point Fort, following the Royalist defeat in the English Civil War.[2]: 50–51

During the Second Anglo-Dutch War, the relationship between the French and English settlers soured, as their home countries warred. On 21 April 1666, French Governor Charles de Sales gathered 800 troops and 150–200 slaves at Palmetto Point. As the French advanced towards Sandy Point, where English Governor William Watts waited, the French were ambushed by 400 English troops and de Sales was killed. Claude de Roux de Saint-Laurent took over command as the French counter-attacked, forcing the English to retreat. On 22 April, during the Battle of Sandy Point, 1,400 English troops under the command of Governor Watts, which included 260 of Colonel Morgan's buccaneers, failed to stop 350 French. Governor Watts was killed, and the English spiked their guns at Fort Charles before fleeing to Old Road Town. Many of the English then fled to Nevis as the French took control of St. Kitts. The French then tried to take Nevis, but were turned back by the English at Pinney's Beach. English reinforcements to Nevis failed to arrive when Willoughby's fleet sank in the 15 August 1666 hurricane. Armes d'Angleterre set out from Basseterre in April 1667 with Joseph-Antoine de La Barre aboard. The French ship encountered HMS Winchester, the start of an English blockade, and engaged in a long running battle before sinking her and eventually returning to St. Kitts. Finally, the English turned back an attempted invasion of Nevis in May 1667 during the Battle of Nevis. However, the Treaty of Breda restored the status quo.[1]: 41–50 [2]: 88–102

The 1670 Treaty of Madrid meant the recognition of English colonies in the Caribbean by Spain in return for the curtailment of pirate attacks. England established the Admiralty Court in Nevis as a consequence. Those found guilty of piracy were hanged at Gallows Bay.[2]: 69

In 1689, during the War of the Grand Alliance, French Governor de Salnave sent troops to plunder the English side, with Irish assistance, while Count de Blanc's fleet arrived in Basseterre with 1,200 troops. The French sieged English Governor Thomas Hill's troops at Fort Charles, forcing their surrender on 15 August 1689. The English were once again sent to Nevis while the Irish took over their plantations. On 24 June 1690, Leeward Islands Governor Sir Christopher Codrington and Sir Timothy Thornhill, operating from Nevis, landed an English force of 3,000 men on St. Kitts. Operating from Timothy's Beach and Frigate Bay, they march into Basseterre and then sieged the French at Fort Charles. The French surrendered on 16 July and were deported to Santo Domingo. The French had used cannon on Brimstone Hill in their 1689 siege, and in 1690 the British began construction on Brimstone Hill Fortress. The Treaty of Rijswijk in 1697 restored the status quo. An interesting side note is that Capt. William Kidd's privateer Blessed William assisted Codrington during this war.[1]: 51–55 [2]: 102–105

In 1690, a massive earthquake and tsunami destroyed the city of Jamestown, then the capital of Nevis. So much damage was done to it that the city was completely abandoned. It is reputed that the whole city sank into the sea, but since then, the land has moved over at least 100 yards (91 m) to the west. That means that anything left of Jamestown would now be underground, near where Fort Ashby was built in 1701. The capital was moved south to the town of Charlestown.[2]: 105–108

Saint Kitts and Nevis (1700–1883)

Saint Kitts and Nevis were to face more devastation during the War of the Spanish Succession, though the local impact of that conflict started with the French Governor of St. Christopher, Count Jean-Baptiste de Gennes, surrendering the island without a fight to Sir Christopher Codrington, governor of the English Leewards, and Colonel Walter Hamilton in 1702. The French inhabitants of St. Kitts were peacefully removed to other islands. The French retaliated in 1705 with a five-day bombardment of Nevis by Admiral Count Louis-Henri de Chavagnac before he proceeded to St. Kitts. There the French pillaged the English quarter after landing on Frigate Bay, carrying off 600–700 slaves. Then on Good Friday 1706, the French under the command of Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville attacked Nevis, capturing Fort Charles then looting and burning Charlestown. Once again, 3,400 slaves were taken, though several more escaped to Maroon Hill and formed a slave army, which effectively resisted a French attack. Before departing Nevis, the French left Nevis in ruins, including its sugar works. The 1707 hurricane did further damage to Nevis. It would be 80 years before sugar production on Nevis reached the level achieved in 1704. The Treaty of Utrecht was signed in 1713, in which the French ceded their portion of St Kitts to the British.[1]: 55–60 [2]: 111–121

By 1720, the population of St. Kitts exceeded that of Nevis for the first time. In 1724, the population of Saint Kitts consisted of 4000 whites and 11,500 blacks, while Nevis had 1,100 whites and 4,400 blacks. By 1774, the population on St. Kitts was 1,900 white and 23,462 black, while Nevis had 1,000 whites and 10,000 blacks.[1]: 75 [2]: 126, 137

Upon gaining control of the whole island in 1713, the British soon moved the island's capital to the town of Basseterre in 1727, and St Kitts quickly took off as a leader in sugar production in the Caribbean. Whilst conditions on St Kitts improved, Nevis was seeing a decline. The years of monocrop cultivation, as well as heavy amounts of soil erosion due to the high slope grade on the island, caused its sugar production to continuously decrease.

Alexander Hamilton, the first United States Secretary of the Treasury, was born in Nevis; he spent his childhood there and on St. Croix, then belonging to Denmark, and now one of the United States Virgin Islands.[2]: 136

James Ramsay (abolitionist) was ordained a priest at Saint John Capisterre Parish in 1762. He continued his abolitionist activities and concern for the welfare of slaves until he left the island in 1781.[1]: 114–115

John Huggins built the first Caribbean resort hotel in 1778. The Bath Hotel was constructed over the site of one of the island's famous hot springs, Bath Spring. The island thus became the first place in the Americas to officially practice tourism. Nevis's popularity as a destination grew, and it continued to be in the favour of the British upper classes, including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Nelson, and Prince William Henry, until it closed in the 1870s. The hotel opened briefly from 1910 to the 1930s, after refurbishment by the Gillespie Brothers. It housed troops in World War II, and the Police Department and Magistrate's Court from 1995 to 1999.[2]: 151–153, 197

By 1776, Saint Kitts had become the richest British colony in the Caribbean, per capita. Attacks by the French occurred at the end of the throughout the 18th century, including the Siege of Brimstone Hill and the Battle of Saint Kitts in 1782. The consolidation of British rule was recognized finally under the Treaty of Versailles in 1783.[1]: 80, 96–103 [2]: 142–147

On 11 March 1787, Captain Nelson was married to Frances Woolward Nisbet, niece of John Herbert, President of the Nevis Council. They were married at Montpelier Plantation, with Prince William Henry acting as best man.[1]: 100–103 [2]: 149–152

In 1799, USS Constellation engaged the French commerce raider L'Insurgent off Nevis during the Quasi-War. The American vessel won a first victory for the United States Navy, bringing the captured French commerce raider back to St. Kitts.[1]: 108 [2]: 161–164

In 1804, the French Admiral Édouard Thomas Burgues de Missiessy and General La Grange forced Nevis and St. Kitts to pay ransoms of 4,000 and 18,000 pounds respectively. This was followed by Jérôme Bonaparte's raid in 1806.[2]: 164–165 [1]: 109

In 1806, the Leeward Islands Caribee government was split into two groups, with Antigua, Barbuda, Redonda and Montserrat in one group, and St Kitts, Nevis, Anguilla and the British Virgin Islands in the other. The islands in the new grouping however, were able to keep their great degrees of autonomy. The grouping then split entirely in 1816.

Lord Combermere bought Russell's Rest Plantation following the defeat of France in the Battle of Waterloo. Combermere Village and School are named after him.[2]: 165

The Roman Catholic religion was practiced by the French, and the Church of England by the English, yet a Jewish synagogue existed on Nevis since 1684. The Moravian Church was established on St. Kitts in 1777, and numbered 2,500 by 1790. Bishop Thomas Coke paid his first of three visits to Nevis and St. Kitts in 1788, establishing the Methodist Church on the island. Membership grew to 1,800 on Nevis and 1,400 on St. Kitts by 1789.[2]: 57–58 [1]: 103–105

In 1824, the Cottle Church was established on Nevis, welcoming slaves and masters alike.[2]: 156

The African slave trade was terminated within the British Empire in 1807, and slavery outlawed in 1834. A four-year "apprenticeship" period followed for each slave, in which they worked for their former owners for wages. On Nevis 8,815 slaves were freed in this way, while St. Kitts had 19,780 freed.[2]: 174 [1]: 110, 114–117

The 1835 hurricane, followed by the drought of 1836–1838 and the fire of 1837, devastated Nevis. Sugar prices continued their decline due to production in other parts of the world where costs were cheaper, so that by 1842, Nevis saw a decline in its population as workers fled the island, if unwilling to stay and make a living sharecropping in Nevis' increasingly less fertile soil. St. Kitts' soil was not so depleted. Then several earthquakes struck in 1843, followed by a cholera epidemic in 1853–54, killing more than 800 on Nevis and 3920 on St. Kitts.[2]: 176–180 [1]: 117, 120

In 1872, St. Kitts was connected to the international telegraph system. However, the connection did not extend to Nevis until 1925.[1]: 129 [2]: 199

The Federation of the Leeward Islands Colony of 1871 meant the end of elected Assemblies, but were instead appointed. In 1883, the governments of St Kitts, Nevis and Anguilla were combined into the St. Kitts Assembly. Of the ten seats in the Assembly, Nevis had two while Anguilla had one.[2]: 186–187 [1]: 123

Saint Kitts and Nevis (1883 – present)

Subsidized beet sugar production put wage pressures on the islands, which resulted in the Portuguese Riots of 1896. It took marines from HMS Cordelia to restore order. By 1900 there were 61 estates on Nevis utilizing the sharecropping system, while St. Kitts only had 2.[1]: 123–124 [2]: 188–189, 191

The 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane left 27 dead on Nevis and 2 on St. Kitts. The Nevis hospital was destroyed and 8,000 left homeless.[2]: 193–194

The St. Kitts Sugar Producers Association built a central factory for sugar refining and a railway for transportation in 1912. The London Electric Theatre opened on St. Kitts in 1917. A telephone system was built on St. Kitts in 1896 and included Nevis by 1913. Nevis' first automobile arrived in 1912, a Ford Model T.[1]: 128, 130, 133 [2]: 198

Theodore Roosevelt and his wife Edith Roosevelt visited St. Kitts in 1916.[1]: 131

Cotton production supplemented sugar during World War I, but declined in 1922 after the boll weevil appeared. The Great Depression meant the government became the largest landowner on Nevis as estates were abandoned or were requisitioned for failure to pay taxes. From 1900 to 1929, the population on St. Kitts declined by 43%, while on Nevis it declined by 9%.[1]: 133–134 [2]: 199–201

In 1951, the islands were granted the right to vote, with the first election held in 1952.[1]: 140–141

Sugar production continued to dominate the lives of the islanders. The dominance by estate owners of the island's only and extremely limited natural resource, the land, and the single-minded application of that resource to one industry precluded the development of a stable peasant class. Instead, the system produced a large class of wage labourers generally resentful of foreign influence. The nature of the sugar industry itself—the production of a nonstaple and essentially nonnutritive commodity for a widely fluctuating world market—only served to deepen this hostility and to motivate Kittitian labourers to seek greater control over their working lives and their political situation. The collapse of sugar prices brought on by the Great Depression precipitated the birth of the organized labour movement in St. Kitts and Nevis. The Workers League, organized by Thomas Manchester of Sandy Point in 1932, tapped the popular frustration that fueled the labor riots of 1935–36. Rechristened the St. Kitts and Nevis Trades and Labour Union in 1940 and under the new leadership of Robert Llewellyn Bradshaw, the union established a political arm, the St. Kitts and Nevis Labour Party, which put Bradshaw in the Legislative Council in 1946. The Labour Party would go on to dominate political life in the twin-island state for more than thirty years.

Electricity first came to Nevis in 1954.[2]: 208

The islands remained in the Leeward Islands Federation until they joined the failed West Indies Federation from 1958 to 1962, in which Saint Christopher-Nevis-Anguilla was a separate state. Robert Bradshaw was the Minister of Finance for the short-lived country.

In 1967, the islands became an Associated State of Britain.

In the same year Anguilla had a major secession movement supported by St. Kitts' political opposition party, The People's Action Movement (PAM). Both forces, working together, invaded the island from an Anguillian base in an attempted coup d'état.[1]: 145–146 Anguilla was able to successfully break away from the union in 1971.

In 1970 there was a serious maritime incident, the Christena disaster, the sinking of an overloaded ferry boat, with much loss of life.[1]: 149–154

During Bradshaw's long tenure, his government slowly moved into a statist approach to economic development in 1972. All sugar lands were bought by the government, as well as the nationalization of the sugar factory in 1976.[1]: 151–152

Opposition to Bradshaw's rule began to build, especially by the families and supporters of former estate owners, who founded the People's Action Movement party in 1964, after frustration over a failed demonstration against a raise in electricity rates. Opposition was especially great in Nevis, who felt that their island was being neglected and unfairly deprived of revenue, investment and services by its larger neighbour. Bradshaw mainly ignored Nevis' complaints, but Nevisian disenchantment with the Labour Party proved a key factor in the party's eventual fall from power.

In 1978 Bradshaw died of prostate cancer. He was succeeded by his former deputy, Paul Southwell, but in 1979, Southwell himself died (under mysterious circumstances) in St. Lucia. Accompanying Interim Premier Caleb Azariah Paul Southwell, was Lee Llewellyn Moore the Attorney General, and next in seniority of the St. Kitts Labour Party. The Political organization eventually fell into a crisis of leadership, but Lee Moore was selected. Regardless, many Labour Supporters had their suspicions about Southwell's death, and many chose to vote "PAM" the following year in the General Elections.

Taking advantage of the Labour Party's confusion, the PAM party was very successful in the 1980 elections, winning three seats on St. Kitts, compared to the Labour Party's four. The Nevis Reformation Party, under the leadership of Simeon Daniel, won two of the three seats on Nevis. PAM and NRP then formed a coalition government, naming Kennedy Simmonds, a medical doctor and one of the founders of the PAM, premier (Simmonds had won Bradshaw's former seat in a 1979 by-election). The change in government reduced the demand for Nevis' secession.

Independence since 1983

In 1983, the federation was granted independence from Britain, with a constitution that granted Nevis a large degree of autonomy as well as the guaranteed right of secession. To take advantage of this landmark, early elections were called in 1984, in which the NRP captured all three seats on Nevis, and the PAM party capturing six seats on St. Kitts, compared to the Labour Party's two, despite overall the Labour Party winning the nationwide popular vote. The new coalition government now had a strong 9 to 2 mandate in parliament.

Economic improvement for St. Kitts followed, with the PAM party shifting focus from the sugar industry to tourism. However, much of the island's poorest people, mainly the sugar workers, were neglected. Opposition to PAM began to build from this, as well as on accusations of corruption. In the 1993 elections, both PAM and Labour took four seats each, whilst on Nevis, a new party, the Concerned Citizens Movement, took two seats, beating the NRP's one. The stalemate on St. Kitts proved unresolvable when the CCM in Nevis refused to form a coalition with PAM. Rioting soon followed on the islands, which was finally resolved in a special set of elections held in 1995, in which the Labour Party overwhelmingly defeated the PAM party, winning seven seats compared to PAM's one. Dr. Denzil Douglas became the new prime minister of the federation.

On 21 September 1998, Hurricane Georges severely damaged the islands, leaving nearly $500 million of damage to property. Georges was the worst hurricane to hit the region in the 20th century.[6]

In 2005, St. Kitts saw the closure of its sugar industry by the Douglas administration, after 365 years in the monoculture. This was explained as due to the industry's huge losses, as well as to market threats by the European Union, which had plans to cut sugar prices greatly in the near future. Since that time tourism has been the main focus of the economy.[7]

The 2015 Saint Kitts and Nevis general election was won by Timothy Harris and his recently formed People's Labour Party, with backing from the PAM and the Nevis-based Concerned Citizens' Movement under the 'Team Unity' banner.[8]

In June 2020, Team Unity coalition of the incumbent government, led by Prime Minister Timothy Harris, won general elections by defeating St. Kitts and Nevis Labour Party (SKNLP).[9]

In the general election on 5 August 2022, Terrance Drew was elected as the fourth and current prime minister of Saint Kitts and Nevis after his St. Kitts-Nevis Labour Party (SKNLP) won snap general election.[10]

See also

- British colonization of the Americas

- French colonization of the Americas

- French settlement in Saint Kitts and Nevis

- History of North America

- History of the Americas

- History of the British West Indies

- History of the Caribbean

- List of colonial governors and administrators of Nevis

- List of colonial governors and administrators of Saint Christopher

- List of governors of the Leeward Islands

- List of prime ministers of Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Politics of Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

- Eden Brown Estate

- Cyril Briggs

- John Burdon

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Hubbard, Vincent (2002). A History of St. Kitts. Macmillan Caribbean. p. 10. ISBN 9780333747605.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Hubbard, Vincent (2002). Swords, Ships & Sugar. Corvallis: Premiere Editions International, Inc. p. 20. ISBN 9781891519055.

- ^ Under the Old Style and New Style dates used in Britain prior to 1752, the new year began on March 25; under the system, "March 25, 1624" was the day after "March 24, 1623"

- ^ Gerard Lafleur; Lucien Abenon (2003). "The Protestants and the Colonization of the French West Indies". In Van Ruymbeke, Bertrand; Sparks, Randy J. (eds.). Memory and Identity, The Huguenots in France and the Atlantic Diaspora. University of South Carolina. p. 267. ISBN 9781570037955.

- ^ T. H. Breen (1973). "George Donne's 'Virginia Reviewed', a 1638 Plan to Reform Colonial Society". The William and Mary Quarterly. 30 (3): 449–466. doi:10.2307/1918484. JSTOR 1918484.

- ^ "Caribbean, Dominican Republic, Haiti - Hurricane Georges Fact Sheet #6 - Antigua and Barbuda". ReliefWeb. September 30, 1998.

- ^ "The Economy of St. Kitts". Archived from the original on April 9, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ Team Unity wins St Kitts and Nevis 2015 general election Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Caribbean Elections, 17 February 2015

- ^ Reporter, WIC News (June 6, 2020). "Election 2020 - Landslide victory for Team Unity in St Kitts and Nevis". WIC News.

- ^ Salmon, Santana (August 8, 2022). "St. Kitts Nevis new PM sworn into office". CNW Network.

Further reading

- Jedidiah Morse (1797), "St. Christophers", The American Gazetteer, Boston, Massachusetts: At the presses of S. Hall, and Thomas & Andrews, OL 23272543M