History of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

| |||||

| Motto: Leo Terram Propriam Protegat (Latin: Let the lion protect its own land) | |||||

The history of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands is relatively recent. When European explorers discovered the islands, they were uninhabited, and their hostile climate, mountainous terrain, and remoteness made subsequent settlement difficult. Due to these conditions, human activity in the islands has largely consisted of sealing, whaling, and scientific surveys and research, interrupted by World War II and the Falklands War.

17th to 19th century

The South Atlantic island of South Georgia, situated south of the Antarctic Convergence, was the first Antarctic territory to be discovered.[1] It was first visited in 1675 by Antoine de la Roché, an English merchant born in London to a French father.[2] He left Hamburg in 1674 as a passenger on a 350-ton vessel bound for Peru.[3] During the return journey, it was en route to Salvador in Brazil around Cape Horn. While trying to navigate through the Le Maire Strait near Staten Island, it was driven off course far to the east. In April 1675, the vessel found refuge in a bay of an unknown island where it anchored for 14 days. La Roché published a report of his voyage in London in 1678 in which he described the new land. That report is now lost but shortly afterwards, in 1690, Captain Francisco de Seixas y Lovera, a Spanish mariner, published an account of La Roché's discovery in his Descripcion geographica, y derrotero de la region austral Magallanica.[4][5] After this, cartographers started to depict "Roché Island" on their maps. Roché Island is almost certainly South Georgia, despite the discrepancies in the coordinates given, which can be accounted for by the navigational difficulties experienced by all sailors at the time.[1]

Sir Edmund Halley in HMS Paramore (or Paramour) made a major scientific discovery in what is now the South Georgia EEZ in January 1700, discovering and describing the Antarctic Convergence.[6]

In 1756, the island was sighted and named 'San Pedro' by the Spanish vessel León under Captain Gregorio Jerez sailing in the service of the French company Sieur Duclos of Saint-Malo, with the merchant and mariner Nicolas Pierre Duclos-Guyot on board.

These early visits resulted in no sovereignty claims. In particular―unlike the case of the Falkland Islands―Spain never claimed South Georgia. The latter anyway fell within the 'Portuguese' portion of the world as envisaged by the 1494 Tordesillas Treaty concluded between Spain and Portugal.

The mariner Captain James Cook in HMS Resolution accompanied by HMS Adventure made the first landing, survey and mapping of South Georgia. As mandated by the Admiralty, on 17 January 1775 he took possession for Britain and renamed the island 'Isle of Georgia' for King George III. German naturalist Georg Forster, who accompanied Cook during their landings in three separate places at Possession Bay on that day, wrote: "Here Captain Cook displayed the British flag, and performed the ceremony of taking possession of those barren rocks, in the name of his Britannic Majesty, and his heirs forever. A volley of two or three muskets was fired into the air." Nowadays the date of 17 January is celebrated as Possession Day, a public holiday in SGSSI.[7]

The group of Shag Rocks and Black Rock forming the west extremity of the British overseas territory of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands is situated 270 km or 150 nmi west by north of the South Georgian mainland. Probably discovered in 1762 by the Spanish ship Aurora, these rocks appeared on early maps as Aurora Islands, were visited and renamed by the American sealer James Sheffield in the Hersilia in 1819, and mapped by HMS Dartmouth in 1920.

South Georgia's coast and waters have been surveyed by a number of expeditions since those of Cook and Bellingshausen. In particular, the extensive oceanographic investigations carried out by the Discovery Committee from 1925 to 1951 yielded an enormous amount of scientific results and data, including the discovery of the Antarctic Convergence. The first land-based scientific expedition on South Georgia was the 1882–83 German Polar Year expedition at Moltke Harbour, Royal Bay.

During the late 18th century and throughout the 19th century, South Georgia was inhabited by English and Yankee sealers, who used to live there for considerable periods of time and sometimes overwintered.[8] The first fur seals from the island were taken in 1786 by the English sealing vessel Lord Hawkesbury, while the first commercial visit to the South Sandwich Islands was made in 1816 by another English ship, the Ann.

The sealers pursued their trade in a most unsustainable manner, promptly reducing the fur seal population to near extermination. As a result, sealing activities on South Georgia had three marked peaks in 1786–1802, 1814–23, and 1869–1913 respectively, decreasing in between and gradually shifting to elephant seals taken for oil. More efficient regulation and management were practised in the second sealing epoch, 1909–64.

During the 19th century, the effective, continuous and unchallenged British possession and government for South Georgia was provided for by the British Letters Patent of 1843, revised in 1876, 1892, 1908 and 1917, with the island appearing in the Colonial Office Yearbook since 1887. From 1881 on, Britain regulated the economic activities and conservation by administrative acts such as the Sealing Ordinances of 1881 and 1899. South Georgia was governed by the United Kingdom as a Falkland Islands Dependency, a distinct entity administered through the Falkland Islands but not part of them in political or financial respect. These constitutional arrangements stayed in place throughout the second half of the 19th century and most of the 20th century, until South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands were incorporated as a distinct British overseas territory in 1985.

20th century

In the early 20th century South Georgia experienced a new rush of economic activity and settlement. Following a 1900 advertisement by the Falklands Government the entire island was leased to a Punta Arenas company, and a subsequent conflict of interests with the Compañía Argentina de Pesca which had started whaling at Grytviken since December 1904 was settled by the British authorities with the company applying for and being granted British whaling lease.

South Georgia became the world's largest whaling centre, with shore bases at Grytviken (operating 1904–64), Leith Harbour (1909–65), Ocean Harbour (1909–20), Husvik (1910–60), Stromness (1912–61) and Prince Olav Harbour (1917–34). The companies involved included Compañía Argentina de Pesca, Christian Salvesen Ltd (UK), Albion Star (South Georgia) Ltd. (Falkland Islands), the Norwegian whaling companies Hvalfangerselskap Ocean, Tønsberg Hvalfangeri and Sandefjord Hvalfangerselskap, as well as the Southern Whaling and Sealing Company (South Africa). The Japanese companies Kokusai Gyogyo Kabushike Kaisha and Nippon Suisan Kaisha sub-leased respectively Grytviken in 1963–64 and Leith Harbour in 1963–65, the last seasons of South Georgia whaling.

(built 1913)

The spread of Norwegian whaling industry to Antarctica in the early 20th century motivated Norway, right after its independence from Sweden in 1905, to pursue territorial expansion not only in the Arctic claiming Jan Mayen and Sverdrup Islands, but also in Antarctica. Norway claimed Bouvet Island and looked further south, formally inquiring of the British Foreign Office about the international status of the area between 45° and 65° south latitude and 35° and 80° west longitude. Following a second such diplomatic démarche by the Norwegian Government dated 4 March 1907, the United Kingdom replied that the areas were British based on discoveries made in the first half of the 19th century, and issued the 1908 Letters Patent incorporating the British Falkland Islands Dependencies with a permanent local administration in Grytviken established in 1909.[9][10]

Britain's 1908 Letters Patent established constitutional arrangements for its possessions in the South Atlantic, including the formal annexation of the South Sandwich Islands. The Letters Patent listed these possessions as "the groups of islands known as South Georgia, the South Orkneys, the South Shetlands, and the Sandwich Islands, and the territory known as Graham's Land, situated in the South Atlantic Ocean to the south of the 50th parallel of south latitude, and lying between the 20th and the 80th degrees of west longitude". In 1917 the Letters Patent were modified, applying the "sector principle" used in the Arctic; the new scope of the Falkland Islands Dependencies was extended to comprise "all islands and territories whatsoever between the 20th degree of west longitude and the 50th degree of west longitude which are situated south of the 50th parallel of south latitude; and all islands and territories whatsoever between the 50th degree of west longitude and the 80th degree of west longitude which are situated south of the 58th parallel of south latitude", thus reaching the South Pole. The 1908 Letters Patent were not disputed by Argentina at the time, but in 1948 Argentina conceived an argument that they were invalid on the grounds that they allegedly encompassed parts of the South American mainland as well as the Falklands, making the latter dependencies of themselves.[11][12][13]

All whaling stations on South Georgia operated under whaling leases applied for by each company and granted by the Governor of the Falkland Islands and Dependencies. On behalf of the Compañía Argentina de Pesca, the application was filed with the British Legation in Buenos Aires by the company's president Pedro Christophersen and Captain Guillermo Nuñez, a technical advisor and shareholder in the company who was also Director of Armaments of the Argentine Navy.

From 1906 on the Argentine company was operating in compliance with its whaling and sealing leases granted by the Falklands Governor. That continued until Grytviken was sold to Albion Star (South Georgia) Ltd. in 1960, closed in 1964, and eventually purchased by Christian Salvesen Ltd.

Carl Anton Larsen, the founder of Grytviken was a naturalised Briton born in Sandefjord, Norway. In his application for British citizenship, filed with the British Magistrate of South Georgia and granted in 1910, Captain Larsen wrote: "I have given up my Norwegian citizens rights and have resided here since I started whaling in this colony on 16 November 1904 and have no reason to be of any other citizenship than British, as I have had and intend to have my residence here still for a long time." His family in Grytviken included his wife, three daughters and two sons.

As the manager of Compañía Argentina de Pesca, Larsen organised the construction of Grytviken ― a remarkable undertaking accomplished by a team of 60 Norwegians since their arrival on 16 November until the newly built whale oil factory commenced production on 24 December 1904. Larsen also established a meteorological observatory at Grytviken, which from 1905 was maintained in cooperation with the Argentine Meteorological Office under the British lease requirements of the whaling station until these changed in 1949.

Larsen chose the whaling station's site during his 1902 visit while in command of the ship Antarctic of the Swedish Antarctic Expedition (1901–03) led by Otto Nordenskjöld. On that occasion, the name Grytviken ('Pot Cove') was given by the Swedish archaeologist and geologist Johan Gunnar Andersson who surveyed part of Thatcher Peninsula and found numerous artefacts and features from sealers' habitation and industry, including a shallop and several try-pots used to boil seal oil. One of those try-pots, having the inscription 'Johnson and Sons, Wapping Dock London' is preserved at the South Georgia Museum in Grytviken.

Larsen was also instrumental, with his brother, in introducing Reindeer to South Georgia in 1911 as a resource for hunting for the people employed in the whaling industry.[14]

Most of the whalers were Norwegian, with an increasing proportion of Britons. During the whaling era, the population usually varied from over 1000 in the summer (over 2000 in some years) to some 200 in the winter. At the height of the whaling industry about 6000 men, mostly Norwegians and Swedes, worked at the stations and, with the men working on the whale-catchers, factory ships and supply vessels, there could be three times the population when the whaling fleets were at anchor in the harbours.[15] The first census conducted by the British Stipendiary Magistrate James Wilson on 31 December 1909 recorded a total population of 720, including 3 females and 1 child. Of them, 579 were Norwegian, 58 Swedes, 32 Britons, 16 Danes, 15 Finns, 9 Germans, 7 Russians, 2 Dutchmen, 1 Frenchman and 1 Austrian. In subsequent available censuses the population was 1337 (24 April 1921[16]), and 709 (26 April 1931,[17] includes the South Shetland Islands).

Managers and other senior officers of the whaling stations often lived together with their families. Among them was Fridthjof Jacobsen whose wife Klara Olette Jacobsen gave birth to two of their children in Grytviken; their daughter Solveig Gunbjörg Jacobsen was the first child ever born in Antarctica, on 8 October 1913. Several more children were born on South Georgia, even recently aboard visiting private yachts.

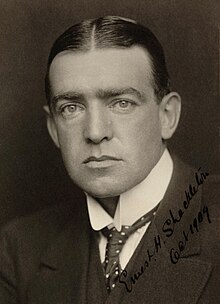

There are some 200 graves on the island dating from 1820 onwards, including that of the famous Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton (died 1922) whose British Antarctic Expedition (1908–09) established the route to the South Pole subsequently followed by Robert Scott. In one of the most remarkable small boat journeys in maritime history (probably rivalled only by that of Bounty's Lieutenant William Bligh), in 1916 Shackleton crossed Scotia Sea in the 7 m or 23' James Caird to reach South Georgia and organise the successful rescue of his expedition team stranded on Elephant Island following the loss of their ship Endurance. In the process, Shackleton accompanied by Frank Worsley and Tom Crean trekked the island's glaciated and rugged terrain between King Haakon Bay and the Stromness whaling station.[18]

Another Antarctic explorer with a special place in South Georgia's history was Duncan Carse. His comprehensive 1951–57 South Georgia Survey resulted in the classical 1:200000 topographic map of South Georgia, occasionally updated but never superseded since its first publication by the British Directorate of Overseas Surveys in 1958. For several months in 1961, Carse experimented on living alone at a remote location, Ducloz Head on the southwest coast of the island. Mount Carse, the island's third highest peak is named for him.

A magistrate conducting the local British administration has been residing in South Georgia ever since November 1909 (except for 22 days in 1982). The 1908 British Letters Patent was transmitted to the Argentine Foreign Ministry and was formally acknowledged on 18 March 1909 without objections. Argentina also recognised de facto the British permanent local administration set up in 1909, with commercial and naval Argentine vessels that visited the island in the subsequent years duly complying with normal harbour, customs, immigration and other procedures.

During the Second World War the whaling stations were closed excepting Grytviken and Leith Harbour. Most of the British and Norwegian whaling factories and catchers were destroyed by German raiders, while the rest were called up to serve under Allied command. The resident British Magistrates (W. Barlas and A.I. Fleuret) attended to the island's defence throughout the War. The Royal Navy armed the merchant vessel Queen of Bermuda to patrol South Georgian and Antarctic waters, and deployed two four-inch (102 mm) guns at key locations protecting the approaches to Cumberland Bay and Stromness Bay, i.e. to Grytviken and Leith Harbour respectively. These batteries (still present) were manned by volunteers from among the Norwegian whalers who were trained for the purpose.

Sovereignty dispute and Falklands War

According to the Papal Bull Inter caetera, issued by Pope Alexander VI on 4 May 1493, the dividing line between the crowns of Spain and Portugal had found the longitude 36 º 8'O, cutting South Georgia (according to other sources in longitude 35 º W). But with the entry into force of the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, the island was in the Portuguese hemisphere. Regarding the South Sandwich Islands, both the bull and the Treaty were within the Portuguese hemisphere.

The first official announcement of an Argentine claim of South Georgia was made in 1927 at the International Postal Bureau in Bern. The first definitive Argentine claim of sovereignty over the South Sandwich Islands was made in 1938, when the President of Argentina ratified the 1934 Cairo Postal Convention. Since then, Argentina has maintained her claims of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands but repeatedly (in 1947, 1951, 1953, 1954 and 1955) refused to have them resolved by the International Court of Justice or by an independent arbitral tribunal.

The Argentine naval station Corbeta Uruguay was clandestinely built on Thule Island, in the South Sandwich Islands on 7 November 1976 and was subject to a number of official British protests, the first of them on 19 January 1977. Arrangements to legitimise the station were discussed in 1978 but failed. At an early stage of the Falklands Conflict, 32 special forces troops from Corbeta Uruguay were brought by the Argentine Navy ship Bahía Paraíso to South Georgia and landed at Leith Harbour on 25 March 1982.

Joined by the corvette ARA Guerrico, on 3 April the Bahía Paraiso attacked the platoon of 22 Royal Marines deployed at Grytviken. The two-hour battle resulted in the Guerrico being damaged and an Argentine helicopter shot down. The Argentine forces sustained three men killed and a number of wounded, with one wounded on the British side. The British commanding officer Lieutenant Keith Mills was awarded a Distinguished Service Cross for the defence of South Georgia. While the British Magistrate and other civilians and military present in Grytviken were removed from South Georgia, another 15 Britons remained beyond Argentine reach. The losses suffered at Grytviken prevented Argentina from occupying the rest of the island, with Bird Island base, and field camps at Schlieper Bay, Lyell Glacier and St. Andrews Bay remaining under British control.

On 25 April 1982 the Royal Navy damaged and captured the Argentine submarine Santa Fe at South Georgia. The Argentine garrison in Grytviken under Lieut.-Commander Luis Lagos surrendered without returning fire, as did the detachment in Leith Harbour commanded by Captain Alfredo Astiz on the following day. Nowadays the date of 26 April is celebrated as Liberation Day, a public holiday in SGSSI.[7]

One of the most famous and legendary signals of the entire Falklands War was made by the British forces' commander after the Argentine surrender at Grytviken: "Be pleased to inform Her Majesty that the White Ensign flies alongside the Union Jack in South Georgia. God save the Queen."[19]

Finally, the Argentine personnel were removed from the South Sandwich Islands by HMS Endurance on 20 June 1982. The recapture of South Georgia, even more remote than the Falkland Islands, and in foul weather conditions proved a major boost to British ambitions in the Falklands War, and a blow to those of Argentina.

Due to evidence of an unauthorised visit to Thule Island, the closed station Corbeta Uruguay was destroyed in January 1983.

Since the Falklands War, the United Kingdom maintained a small garrison of Royal Engineers on South Georgia until March 2001,[citation needed] when the island reverted to civilian rule. However, Argentina continues to claim South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

Recent history

In 1985, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands ceased to be Falkland Islands dependencies and became a separate British overseas territory.

Due to its remote location and harsh climate, South Georgia had no indigenous population when first discovered. While the island has been inhabited during the last two centuries, with some settlers residing for decades there and children being born and raised, no families have become established for more than one generation so far. The present permanent centres of population include Grytviken, King Edward Point and Bird Island. King Edward Point is the port of entry, and residence of the British Magistrate and harbour, customs, immigration, fisheries, and postal authorities; it is commonly referred to as 'Grytviken' in association with the derelict whaling station situated just 800 m away. The government of the islands maintains field huts at Sörling Valley, Dartmouth Point, Maiviken, St. Andrews Bay, Corral Bay, Carlita Bay, Jason Harbour, Ocean Harbour, and Lyell Glacier.

Since the 1990s, the islands have become a popular tourist destination, with cruise ships visiting on a fairly regular basis. To protect the territory's unique environment, on 23 February 2012 its government created the South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands Marine Protection Area, one of the world's largest marine reserves, comprising 1.07 million square kilometres (0.41×106 sq mi).[20][21]

Old maps

- L'Isle, Guillaume de & Henry A. Chatelain. (1705/19). Carte du Paraguai, du Chili, du Detroit de Magellan. Paris. (Map featuring Roché Island.)

- Seale, Richard W. (ca. 1745). A Map of South America. With all the European Settlements & whatever else is remarkable from the latest & best observations. London. (Map featuring Roché Island.)

- Jefferys, Thomas. (1768). South America. London. (Map featuring Roché Island.)

- Joseph Gilbert. (1775). Isle of Georgia with Clerke's Isles and Pickersgill's Isle. Plan with panorama. In: Charts, and views of headlands, taken during Captain Cook's Second Voyage, 1772–1774. British Library.

- Cook, James. (1777). Chart of the Discoveries made in the South Atlantic Ocean, in His Majestys Ship Resolution, under the Command of Captain Cook, in January 1775, W. Strahan and T. Cadel, London.

- A. Arrowsmith. (1794). Map of the World on a Globular Projection, Exhibiting Particularly the Nautical Researches of Capn. James Cook, F.R.S. with all the Recent Discoveries to the Present Time. London.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Headland, Robert (1984). The Island of South Georgia. CUP Archive, 1992. pp. 21–22. ISBN 9780521424745. Retrieved 28 August 2019. (A concise 1982 version of the book)

- ^ L. Ivanov and N. Ivanova. Roché Island / South Georgia. In: The World of Antarctica. Generis Publishing, 2022. pp. 68–70. ISBN 979-8-88676-403-1

- ^ Sally Poncet; Kim Crosbie (2005). A Visitor's Guide to South Georgia (Second ed.). Princeton University Press, 2012. p. 31. ISBN 9780691156583. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ Capt. Francisco de Seixas y Lovera, Descripcion geographica, y derrotero de la region austral Magallanica. Que se dirige al Rey nuestro señor, gran monarca de España, y sus dominios en Europa, Emperador del Nuevo Mundo Americano, y Rey de los reynos de la Filipinas y Malucas, Madrid, Antonio de Zafra, 1690. (Narrates the discovery of South Georgia by the Englishman Anthony de la Roché in April 1675 (Capítulo IIII Título XIX page 27 or page 99 of pdf); Relevant fragment.)

- ^ Alexander Dalrymple. A Collection of Voyages Chiefly in The Southern Atlantick Ocean. London, 1775. pp.85-88.

- ^ Alan Gurney. Below the Convergence: Voyages Toward Antarctica, 1699–1839. New York: Penguin Books, 1998.

- ^ a b Public Holidays 2013. Public Holidays 2014. Archived 6 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands Gazette No. 2, 13 June 2013. p. 3.

- ^ R.K. Headland. Chronological List of Antarctic Expeditions and Related Historical Events. Cambridge University Press, 1989. 730 pp.

- ^ Odd Gunnar Skagestad. Norsk Polar Politikk: Hovedtrekk og Utvikslingslinier, 1905–1974. Oslo: Dreyers Forlag, 1975

- ^ Thorleif Tobias Thorleifsson. Bi-polar international diplomacy: The Sverdrup Islands question, 1902–1930. Master of Arts Thesis, Simon Fraser University, 2004.

- ^ National Interests and Claims in the Antarctic Archived 11 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, p. 19, Robert E. Wilson

- ^ R.K. Headland, The Island of South Georgia, Cambridge University Press, 1984.

- ^ The Ross Dependency. The Geographical Journal, Vol. 62, No. 5 (Nov. 1923), pp. 362–365.

- ^ Bell, Cameron M. & Dieterich, Robert A. (2010). "Translocation of reindeer from South Georgia to the Falkland Islands". Rangifer. 30 (1): 1–9. doi:10.7557/2.30.1.247. hdl:10535/6453.

- ^ R. Fox. Antarctica and the South Atlantic: Discovery, Development, and Dispute. British Broadcasting Corp., 1985. p. 31

- ^ Falkland Islands:Report of Census, 1921. Archived 13 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine London: Waterlow & Sons Ltd., 1922. 12 pp.

- ^ Falkland Islands:Report of Census, 1931. Archived 13 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine Stanley, Falkland Islands: Government Printing Office, 1931. 15 pp.

- ^ Carol Fowl. Unplanned epics – Bligh's and Shackleton's small-boat voyages, website of the National Maritime Museum, first published in the magazine Sailing Today, Issue 75, July 2003.

- ^ "Remarks on the recapture of South Georgia", Margaret Thatcher Foundation

- ^ Marine Protected Areas Order 2012. South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands Gazette, 29 February 2012.

- ^ "South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands: Marine Protected Area Management Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

References

- Capt. Francisco de Seixas y Lovera, Descripcion geographica, y derrotero de la region austral Magallanica. Que se dirige al Rey nuestro señor, gran monarca de España, y sus dominios en Europa, Emperador del Nuevo Mundo Americano, y Rey de los reynos de la Filipinas y Malucas, Madrid, Antonio de Zafra, 1690. (Narrates the discovery of South Georgia by the Englishman Anthony de la Roché in April 1675 (Capítulo IIII Título XIX page 27 or page 99 of pdf); Relevant fragment.)

- William Ambrosia Cowley, Cowley's Voyage Round the Globe, in Collection of Original Voyages, ed. William Hacke, James Knapton, London, 1699.

- George Forster, A Voyage Round the World in His Britannic Majesty's Sloop Resolution Commanded by Capt. James Cook, during the Years 1772, 3, 4 and 5 (2 vols.), London, 1777.

- James Cook, A Voyage Towards the South Pole, and Round the World. Performed in His Majesty's Ships the Resolution and Adventure, In the Years 1772, 1773, 1774, and 1775. In which is included, Captain Furneaux's Narrative of his Proceedings in the Adventure during the Separation of the Ships. Volume II. London: Printed for W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1777. (Relevant fragment)

- Capt. Isaac Pendleton, South Georgia; Southatlantic Ocean: Discovered by the Frenchman La Roche in the year 1675, 1802, reproduced by A. Faustini, Rome, 1906. (The second map of South Georgia; Pendleton was misled about the nationality of la Roché who, being an Englishman born in London, had a French father.)

- South Georgia, Topographic map, 1:200000, DOS 610 Series, Directorate of Overseas Surveys, Tolworth, UK, 1958.

- Otto Nordenskjöld, Johan G. Andersson, Carl A. Larsen, Antarctica, or Two Years Among the Ice of the South Pole, London, Hurst & Blackett, 1905.

- R.K. Headland, South Georgia: A Concise Account. Cambridge: British Antarctic Survey, 1982. 30 pp.

- R.K. Headland, The Island of South Georgia, Cambridge University Press, 1984. ISBN 0-521-25274-1

- Roger Perkins, Operation Paraquat, Picton (Chippenham), 1986, ISBN 0-948251-13-1 (Describes the Argentine invasion and defeat of 1982)

- Sally Poncet and Kim Crosbie, A Visitor's Guide to South Georgia, Wildguides 2005, ISBN 1-903657-08-3

- Historia de las Relaciones Exteriores Argentinas, Obra dirigida por Carlos Escudé y Andrés Cisneros, desarrollada y publicada bajo los auspicios del Consejo Argentino para las Relaciones Internacionales (CARI), GEL/Nuevohacer (Buenos Aires), 2000.

- Capt. Hernán Ferrer Fougá. El hito austral del confín de América. El cabo de Hornos. (Siglos XVI-XVII-XVIII). (Primera parte). Revista de Marina, Valparaíso, 2003, No. 6.