History of sugar

The history of sugar has five main phases:

- The extraction of sugar cane juice from the sugarcane plant, and the subsequent domestication of the plant in tropical India and Southeast Asia sometime around 4,000 BC.

- The invention of manufacture of cane sugar granules from sugarcane juice in India a little over two thousand years ago, followed by improvements in refining the crystal granules in India in the early centuries AD.

- The spread of cultivation and manufacture of cane sugar to the medieval Islamic world together with some improvements in production methods.

- The spread of cultivation and manufacture of cane sugar to the West Indies and tropical parts of the Americas beginning in the 16th century, followed by more intensive improvements in production in the 17th through 19th centuries in that part of the world.

- The development of beet sugar, high-fructose corn syrup and other sweeteners in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Sugar was first produced from sugarcane plants in India sometime after the first century AD.[1] The derivation of the word "sugar" is thought to be from Sanskrit शर्करा (śarkarā), meaning "ground or candied sugar," originally "grit, gravel". Sanskrit literature from ancient India, written between 1500 and 500 BC provides the first documentation of the cultivation of sugar cane and of the manufacture of sugar in the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent.[2][3]

Known worldwide by the end of the medieval period, sugar was very expensive[4] and was considered a "fine spice",[5] but from about the year 1500, technological improvements and New World sources began turning it into a much cheaper bulk commodity.[6]

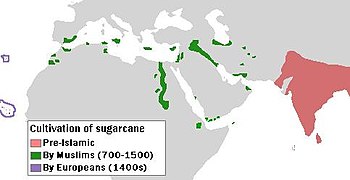

The spread of sugarcane cultivation

There are two centers of domestication for sugarcane: one for Saccharum officinarum by Papuans in New Guinea and another for Saccharum sinense by Austronesians in Taiwan and southern China. Papuans and Austronesians originally primarily used sugarcane as food for domesticated pigs. The spread of both S. officinarum and S. sinense is closely linked to the migrations of the Austronesian peoples. Saccharum barberi was only cultivated in India after the introduction of S. officinarum.[8][9]

Saccharum officinarum was first domesticated in New Guinea and the islands east of the Wallace Line by Papuans, where it is the modern center of diversity. Beginning at around 6,000 BP they were selectively bred from the native Saccharum robustum. From New Guinea it spread westwards to Island Southeast Asia after contact with Austronesians, where it hybridized with Saccharum spontaneum.[9]

The second domestication center is mainland southern China and Taiwan where S. sinense was a primary cultigen of the Austronesian peoples. Words for sugarcane exist in the Proto-Austronesian languages in Taiwan, reconstructed as *təbuS or **CebuS, which became *tebuh in Proto-Malayo-Polynesian. It was one of the original major crops of the Austronesian peoples from at least 5,500 BP. Introduction of the sweeter S. officinarum may have gradually replaced it throughout its cultivated range in Island Southeast Asia.[10][11][7][12][13]

From Island Southeast Asia, S. officinarum was spread eastward into Polynesia and Micronesia by Austronesian voyagers as a canoe plant by around 3,500 BP. It was also spread westward and northward by around 3,000 BP to China and India by Austronesian traders, where it further hybridized with Saccharum sinense and Saccharum barberi. From there it spread further into western Eurasia and the Mediterranean.[9][7]

India, where the process of refining cane juice into granulated crystals was developed, was often visited by imperial convoys (such as those from China) to learn about cultivation and sugar refining.[14] By the sixth century AD, sugar cultivation and processing had reached Persia. In the Mediterranean, sugarcane was possibly brought through the Arab medieval expansion.[15] "Wherever they went, the medieval Arabs brought with them sugar, the product and the technology of its production."[16]

Spanish and Portuguese exploration and conquest in the fifteenth century carried sugar south-west of Iberia. Henry the Navigator introduced cane to Madeira in 1425, while the Spanish, having eventually subdued the Canary Islands, introduced sugar cane to them.[15] In 1493, on his second voyage, Christopher Columbus carried sugarcane seedlings to the New World, in particular Hispaniola.[15]

Early use of sugarcane in India

Sugarcane originated in tropical Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia.[17][18] Different species likely originated in different locations with S. barberi originating in India and S. edule and S. officinarum coming from New Guinea.[18] Originally, people chewed sugarcane raw to extract its sweetness. Indians discovered how to crystallize sugar during the Gupta Empire, c. 350 AD[19] although literary evidence from Indian treatises such as Arthashastra in the 2nd century AD indicates that refined sugar was already being produced in India.[20]

Indian sailors, consumers of clarified butter and sugar, carried sugar by various trade routes.[19] Travelling Buddhist monks brought sugar crystallization methods to China.[21] During the reign of Harsha (r. 606–647) in North India, Indian envoys in Tang China taught sugarcane cultivation methods after Emperor Taizong of Tang (r. 626–649) made his interest in sugar known, and China soon established its first sugarcane cultivation in the seventh century.[22] Chinese documents confirm at least two missions to India, initiated in 647 AD, for obtaining technology for sugar-refining.[23] In India,[17] the Iran[24][25][26] and China, sugar became a staple of cooking and desserts.

Early refining methods involved grinding or pounding the cane in order to extract the juice, and then boiling down the juice or drying it in the sun to yield sugary solids that looked like gravel. The Sanskrit word for "sugar" (sharkara) also means "gravel" or "sand".[27] In Persian: shakar (Traditional Persian: شکر ) (the root of the world word sugar from Persian shakar,[28] which is from Sanskrit śarkarā) means sweetening seeds in Farsi.[29][28] Similarly, the Chinese use the term "gravel sugar" (Traditional Chinese: 砂糖) for what is known in the west as "table sugar".

In 1792, sugar prices soared in Great Britain. On 15 March 1792, his Majesty's Ministers to the British parliament presented a report related to the production of refined sugar in British India. Lieutenant J. Paterson, of the Bengal Presidency, reported that refined sugar could be produced in India with many superior advantages, and a lot more cheaply than in the West Indies.[30]

Cane sugar in the medieval era in the Muslim World and Europe

There are records of knowledge of sugar among the ancient Greeks and Romans, but only as an imported medicine, and not as a food. For example, the Greek physician Dioscorides in the 1st century (AD) wrote: "There is a kind of coalesced honey called sakcharon [i.e. sugar] found in reeds in India and Eudaimon Arabia [i.e. Yemen[32]] similar in consistency to salt and brittle enough to be broken between the teeth like salt. It is good dissolved in water for the intestines and stomach, and [can be] taken as a drink to help [relieve] a painful bladder and kidneys."[33] Pliny the Elder, a 1st-century (AD) Roman, also described sugar as medicinal: "Sugar is made in Arabia as well, but Indian sugar is better. It is a kind of honey found in cane, white as gum, and it crunches between the teeth. It comes in lumps the size of a hazelnut. Sugar is used only for medical purposes."[34]

During the medieval era, Arab entrepreneurs adopted sugar production techniques from India and expanded the industry. Medieval Arabs in some cases set up large plantations equipped with on-site sugar mills or refineries. The cane sugar plant, which is native to a tropical climate, requires both a lot of water and a lot of heat to thrive. The cultivation of the plant spread throughout the medieval Arab world using artificial irrigation. Sugar cane was first grown extensively in medieval Southern Europe during the period of Arab rule in Sicily beginning around the 9th century.[35][36] In addition to Sicily, Al-Andalus (in what is currently southern Spain) was an important center of sugar production, beginning by the tenth century.[37][38]

From the Arab world, sugar was exported throughout Europe. The volume of imports increased in the later medieval centuries as indicated by the increasing references to sugar consumption in late medieval Western writings. But cane sugar remained an expensive import. Its price per pound in 14th and 15th century England was about equally as high as imported spices from tropical Asia such as mace (nutmeg), ginger, cloves, and pepper, which had to be transported across the Indian Ocean in that era.[4]

Clive Ponting traces the spread of the cultivation of sugarcane from its introduction into Mesopotamia, then the Levant and the islands of the eastern Mediterranean, especially Cyprus, by the 10th century.[39] He also notes that it spread along the coast of East Africa to reach Zanzibar.[39]

Crusaders brought sugar home with them to Europe after their campaigns in the Holy Land, where they encountered caravans carrying what they called "sweet salt".[40] Early in the 12th century, Venice acquired some villages near Tyre and set up estates to produce sugar for export to Europe, where it supplemented honey as the only other available sweetener.[41] Crusade chronicler William of Tyre, writing in the late 12th century, described sugar as "a most precious product, very necessary for the use and health of mankind".[42] The first record of sugar in English is in the late 13th century.[43]

Ponting recounts the reliance on slavery of the early European sugar entrepreneurs:

The crucial problem with sugar production was that it was highly labour-intensive in both growing and processing. Because of the huge weight and bulk of the raw cane it was very costly to transport, especially by land, and therefore each estate had to have its own factory. There the cane had to be crushed to extract the juices, which were boiled to concentrate them, in a series of backbreaking and intensive operations lasting many hours. However, once it had been processed and concentrated, the sugar had a very high value for its bulk and could be traded over long distances by ship at a considerable profit. The [European sugar] industry only began on a major scale after the loss of the Levant to a resurgent Islam and the shift of production to Cyprus under a mixture of Crusader aristocrats and Venetian merchants. The local population on Cyprus spent most of their time growing their own food and few would work on the sugar estates. The owners therefore brought in slaves from the Black Sea area (and a few from Africa) to do most of the work. The level of demand and production was low and therefore so was the trade in slaves — no more than about a thousand people a year. It was not much larger when sugar production began in Sicily.

In the Atlantic ocean [the Canaries, Madeira, and the Cape Verde Islands], once the initial exploitation of the timber and raw materials was over, it rapidly became clear that sugar production would be the most profitable way of getting money from the new territories. The problem was the heavy labour involved because the Europeans refused to work except as supervisors. The solution was to bring in slaves from Africa. The crucial developments in this trade began in the 1440's...[41]

During the 1390s, a better press was developed, which doubled the amount of juice that was obtained from the sugarcane and helped to cause the economic expansion of sugar plantations to Andalusia and to the Algarve. It started in Madeira in 1455, using advisers from Sicily and (largely) Genoese capital for the mills. The accessibility of Madeira attracted Genoese and Flemish traders keen to bypass Venetian monopolies. "By 1480 Antwerp had some seventy ships engaged in the Madeira sugar trade, with the refining and distribution concentrated in Antwerp. The 1480's saw sugar production extended to the Canary Islands. By the 1490's Madeira had overtaken Cyprus as a producer of sugar."[44] African slaves also worked in the sugar plantations of the Kingdom of Castile around Valencia.[44]

Sugar cultivation in the New World

The Portuguese took sugar to Brazil. By 1540, there were 800 cane sugar mills in Santa Catarina Island and there were another 2,000 on the north coast of Brazil, Demarara, and Surinam. The first sugar harvest happened in Hispaniola in 1501; and many sugar mills had been constructed in Cuba and Jamaica by the 1520s.[45]

The approximately 3,000 small sugar mills that were built before 1550 in the New World created an unprecedented demand for cast iron gears, levers, axles and other implements. Specialist trades in mold-making and iron casting developed in Europe due to the expansion of sugar production. Sugar mill construction sparked development of the technological skills needed for a nascent industrial revolution in the early 17th century.[45]

After 1625, the Dutch transported sugarcane from South America to the Caribbean islands, where it was grown from Barbados to the Virgin Islands.[citation needed]

Contemporaries often compared the worth of sugar with valuable commodities including musk, pearls, and spices. Sugar prices declined slowly as its production became multi-sourced throughout the European colonies. Once an indulgence only of the rich, the consumption of sugar also became increasingly common among the poor as well. Sugar production increased in the mainland North American colonies, in Cuba, and in Brazil. The labour force at first included European indentured servants and local Native American, and African enslaved people. However, European diseases such as smallpox and African ones such as malaria and yellow fever soon reduced the numbers of local Native Americans.[45] Europeans were also very susceptible to malaria and yellow fever, and the supply of indentured servants was limited. African enslaved people became the dominant source of plantation workers, because they were more resistant to malaria and yellow fever, and because the supply of enslaved people was abundant on the African coast.[46][47]

"When we work at the sugar-canes, and the mill snatches hold of a finger, they cut off the hand; and when we attempt to run away, they cut off the leg; both cases have happened to me. This is the price at which you eat sugar in Europe."

In the process of whitening sugar, the charred bones of dead enslaved people often supplemented the traditionally used animal bones.[48]

During the 18th century, sugar became enormously popular. Great Britain, for example, consumed five times as much sugar in 1770 as in 1710.[49] By 1750, sugar surpassed grain as "the most valuable commodity in European trade — it made up a fifth of all European imports and in the last decades of the century four-fifths of the sugar came from the British and French colonies in the West Indies."[49] From the 1740s until the 1820s, sugar was Britain's most valuable import.[50]

The sugar market went through a series of booms. The heightened demand and production of sugar came about to a large extent due to a great change in the eating habits of many Europeans. For example, they began consuming jams, candy, tea, coffee, cocoa, processed foods, and other sweet victuals in much greater amounts. Reacting to this increasing trend, the Caribbean islands took advantage of the situation and set about producing still more sugar. In fact, they produced up to ninety percent of the sugar that the western Europeans consumed. Some islands proved more successful than others when it came to producing the product. In Barbados and the British Leeward Islands, sugar provided 93% and 97% respectively of exports.

Planters later began developing ways to boost production even more. For example, they began using more farming methods when growing their crops. They also developed more advanced mills and began using better types of sugarcane. In the eighteenth century "the French colonies were the most successful, especially Saint-Domingue, where better irrigation, water-power and machinery, together with concentration on newer types of sugar, increased profits."[49] Despite these and other improvements, the price of sugar reached soaring heights, especially during events such as the revolt against the Dutch[51] and the Napoleonic Wars. Sugar remained in high demand, and the islands' planters knew exactly how to take advantage of the situation.

As Europeans established sugar plantations on the larger Caribbean islands, prices fell in Europe. By the 18th century all levels of society had become common consumers of the former luxury product. At first most sugar in Britain went into tea, but later confectionery and chocolates became extremely popular. Many Britons (especially children) also ate jams.[52] Suppliers commonly sold sugar in the form of a sugarloaf and consumers required sugar nips, a pliers-like tool, to break off pieces.

Sugarcane quickly exhausts the soil in which it grows, and planters pressed larger islands with fresher soil into production in the nineteenth century as demand for sugar in Europe continued to increase: "average consumption in Britain rose from four pounds per head in 1700 to eighteen pounds in 1800, thirty-six pounds by 1850 and over one hundred pounds by the twentieth century."[53] In the 19th century Cuba rose to become the richest land in the Caribbean (with sugar as its dominant crop) because it formed the only major island landmass free of mountainous terrain. Instead, nearly three-quarters of its land formed a rolling plain — ideal for planting crops. Cuba also prospered above other islands because Cubans used better methods when harvesting the sugar crops: they adopted modern milling methods such as watermills, enclosed furnaces, steam engines, and vacuum pans. All these technologies increased productivity. Cuba also retained slavery longer than most of the rest of the Caribbean islands.[54]

After the Haitian Revolution established the independent state of Haiti, sugar production in that country declined and Cuba replaced Saint-Domingue as the world's largest producer.[citation needed]

Long established in Brazil, sugar production spread to other parts of South America, as well as to newer European colonies in Africa and in the Pacific, where it became especially important in Fiji. Mauritius, Natal and Queensland in Australia started growing sugar. The older and newer sugar production areas now tended to use indentured labour rather than enslaved people, with workers "shipped across the world ... [and] ... held in conditions of near slavery for up to ten years... In the second half of the nineteenth century over 450,000 indentured labourers went from India to the British West Indies, others went to Natal, Mauritius and Fiji (where they became a majority of the population). In Queensland workers from the Pacific islands were moved in. On Hawaii, they came from China and Japan. The Dutch transferred large numbers of people from Java to Surinam."[55] It is said that the sugar plantations would not have thrived without the aid of the African enslaved people. In Colombia, the planting of sugar started very early on, and entrepreneurs imported many African enslaved people to cultivate the fields. The industrialization of the Colombian industry started in 1901 with the establishment of Manuelita, the first steam-powered sugar mill in South America, by Latvian Jewish immigrant James Martin Eder.

The rise of beet sugar

Sugar was a luxury in Europe until the early 19th century, when it became more widely available, due to the rise of beet sugar in Prussia, and later in France under Napoleon.[56] Beet sugar was a German invention, since, in 1747, Andreas Sigismund Marggraf announced the discovery of sugar in beets and devised a method using alcohol to extract it.[57] Marggraf's student, Franz Karl Achard, devised an economical industrial method to extract the sugar in its pure form in the late 18th century.[58][59] Achard first produced beet sugar in 1783 in Kaulsdorf. In 1801, under the patronage of King Frederick William III of Prussia (reigned 1797–1840), the world's first beet sugar production facility was established in Cunern, Silesia (then part of Prussia).[60] While never profitable, this plant operated from 1801 until its destruction during the Napoleonic Wars (ca. 1802–1815).[citation needed]

The works of Marggraf and Achard were the starting point for the sugar industry in Europe,[61] and for the modern sugar industry in general, since sugar was no longer a luxury product and a product almost only produced in warmer climates.[62]

In France, Napoleon cut off from Caribbean imports by a British blockade, and at any rate not wanting to fund British merchants, banned imports of sugar in 1813 and ordered the planting of 32,000 hectares with beetroot.[63] A beet sugar industry emerged, especially after Jean-Baptiste Quéruel industrialized the operation of Benjamin Delessert.

The United Kingdom Beetroot Sugar Association was established in 1832 but efforts to establish sugar beet in the UK were not very successful. Sugar beets provided approximately 2/3 of world sugar production in 1899. 46% of British sugar came from Germany and Austria. Sugar prices in Britain collapsed towards the end of the 19th century. The British Sugar Beet Society was set up in 1915 and by 1930 there were 17 factories in England and one in Scotland, supported under the provisions of the British Sugar (Subsidy) Act 1925. By 1935 homegrown sugar was 27.6% of British consumption. By 1929 109,201 people were employed in the British sugar beet industry, with about 25,000 more casual labourers.[64]

Mechanization

Beginning in the late 18th century, the production of sugar became increasingly mechanized. The steam engine first powered a sugar mill in Jamaica in 1768, and soon after, steam replaced direct firing as the source of process heat.

In 1813 the British chemist Edward Charles Howard invented a method of refining sugar that involved boiling the cane juice not in an open kettle, but in a closed vessel heated by steam and held under partial vacuum. At reduced pressure, water boils at a lower temperature, and this development both saved fuel and reduced the amount of sugar lost through caramelization. Further gains in fuel-efficiency came from the multiple-effect evaporator, designed by the United States engineer Norbert Rillieux (perhaps as early as the 1820s, although the first working model dates from 1845). This system consisted of a series of vacuum pans, each held at a lower pressure than the previous one. The vapors from each pan served to heat the next, with minimal heat wasted. Modern industries use multiple-effect evaporators for evaporating water.

The process of separating sugar from molasses also received mechanical attention: David Weston first applied the centrifuge to this task in Hawaii in 1852.

Other sweeteners

In the United States and Japan, high-fructose corn syrup has replaced sugar in some uses, particularly in soft drinks and processed foods.

The process by which high-fructose corn syrup is produced was first developed by Richard O. Marshall and Earl R. Kooi in 1957.[65] The industrial production process was refined by Dr. Y. Takasaki at Agency of Industrial Science and Technology of Ministry of International Trade and Industry of Japan in 1965–1970. High-fructose corn syrup was rapidly introduced to many processed foods and soft drinks in the United States from around 1975 to 1985.

A system of sugar tariffs and sugar quotas imposed in 1977 in the United States significantly increased the cost of imported sugar and U.S. producers sought cheaper sources. High-fructose corn syrup, derived from corn, is more economical because the domestic U.S. price of sugar is twice the global price[66] and the price of corn is kept low through government subsidies paid to growers.[67][68] High-fructose corn syrup became an attractive substitute, and is preferred over cane sugar among the vast majority of American food and beverage manufacturers. Soft drink makers such as Coca-Cola and Pepsi use sugar in other nations, but switched to high-fructose corn syrup in the United States in 1984.[69]

The average American consumed approximately 37.8 lb (17.1 kg) of high-fructose corn syrup in 2008, versus 46.7 lb (21.2 kg) of sucrose.[70]

In recent years it has been hypothesized that the increase of high-fructose corn syrup usage in processed foods may be linked to various health conditions, including metabolic syndrome, hypertension, dyslipidemia, hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, and obesity. However, there is to date little evidence that high-fructose corn syrup is any unhealthier, calorie for calorie, than sucrose or other simple sugars. The fructose content and fructose:glucose ratio of high-fructose corn syrup do not differ markedly from clarified apple juice.[71] Some researchers hypothesize that fructose may trigger the process by which fats are formed, to a greater extent than other simple sugars.[72] However, most commonly used blends of high-fructose corn syrup contain a nearly one-to-one ratio of fructose and glucose, just like common sucrose, and should therefore be metabolically identical after the first steps of sucrose metabolism, in which the sucrose is split into fructose and glucose components. At the very least, the increasing prevalence of high-fructose corn syrup has certainly led to an increase in added sugar calories in food, which may reasonably increase the incidence of these and other diseases.[73]

See also

- Sugar Cane and Rum Museum

- Castillo Serrallés

- Hacienda Mercedita

- Food history

- Sugar industry

- Sugar Museum (Berlin)

Notes

- ^ Sato 2014, p. 1.

- ^ Galloway, J. H. (2005-11-10). The Sugar Cane Industry: An Historical Geography from Its Origins to 1914. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02219-4.

- ^ "Sugarcane". Farmers' Portal. Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ^ a b One source for the price of cane sugar in late medieval England is the annual account books of a large abbey at Durham, which recorded the purchases of many different goods for use in the abbey, including sugar and various spices, giving the quantity bought and the price paid, with records existing for many years in the 14th and 15th centuries. Selections from these account books are online in two volumes at Archive.org: Extracts from the Account Rolls of the Abbey of Durham. In the Durham Abbey account books the word for sugar is spelled Zuker (year 1299), succre (1309), sucore (1311), Zucar (1316), suker (1323), Zuccoris (1326), Succoris (1329), sugre (1363), suggir (1440).

- ^ Bernstein 2009, p. 205.

- ^ Bernstein 2009, p. 207.

- ^ a b c Daniels, Christian; Menzies, Nicholas K. (1996). Needham, Joseph (ed.). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part 3, Agro-Industries and Forestry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 177–185. ISBN 9780521419994.

- ^ Daniels, John; Daniels, Christian (April 1993). "Sugarcane in Prehistory". Archaeology in Oceania. 28 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4453.1993.tb00309.x.

- ^ a b c Paterson, Andrew H.; Moore, Paul H.; Tom L., Tew (2012). "The Gene Pool of Saccharum Species and Their Improvement". In Paterson, Andrew H. (ed.). Genomics of the Saccharinae. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 43–72. ISBN 9781441959478.

- ^ Blust, Robert (1984–1985). "The Austronesian Homeland: A Linguistic Perspective". Asian Perspectives. 26 (1): 44–67. hdl:10125/16918.

- ^ Spriggs, Matthew (2 January 2015). "Archaeology and the Austronesian expansion: where are we now?". Antiquity. 85 (328): 510–528. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00067910. S2CID 162491927.

- ^ Aljanabi, Salah M. (1998). "Genetics, phylogenetics, and comparative genetics of Saccharum L., a polysomic polyploid Poales: Andropogoneae". In El-Gewely, M. Raafat (ed.). Biotechnology Annual Review. Vol. 4. Elsevier Science B.V. pp. 285–320. ISBN 9780444829719.

- ^ Baldick, Julian (2013). Ancient Religions of the Austronesian World: From Australasia to Taiwan. I.B.Tauris. p. 2. ISBN 9780857733573.

- ^ "SKIL - History of Sugar". www.sucrose.com.

- ^ a b c Parker 2011, p. 10.

- ^ Mintz 1986, p. 25.

- ^ a b Moxham, Roy (7 February 2002). The Great Hedge of India: The Search for the Living Barrier that Divided a People. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-7867-0976-2.

- ^ a b Sharpe 1998.

- ^ a b Adas 2001, p. 311.

- ^ Trautmann, Thomas R. (2012). Arthashastra: The Science of Wealth. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-670-08527-9.

- ^ Kieschnick 2003.

- ^ Sen 2003, pp. 38–40.

- ^ Kieschnick 2003, p. 258.

- ^ Cockayne, Debra; Sterling, Kenneth M.; Shull, Susan; Mintz, Keith P.; Illeyne, Sharon; Cutroneo, Kenneth R. (1986-06-03). "Glucocorticoids decrease the synthesis of type I procollagen mRNAs". Biochemistry. 25 (11): 3202–3209. doi:10.1021/bi00359a018. ISSN 0006-2960. PMID 2425847.

- ^ "Literaturverzeichnis", Histoire noire, transcript Verlag, pp. 378–394, 2007-12-31, doi:10.1515/9783839406953-ref, ISBN 978-3-89942-695-3, retrieved 2024-03-13

- ^ Adas, Michael; American Historical Association, eds. (2001). Agricultural and pastoral societies in ancient and classical history. Critical perspectives on the past. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-56639-832-9.

- ^ "sugar, n." OED Online, Oxford University Press, June 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/193624. Accessed 25 July 2018.

- ^ a b "SUCRE : Etymologie de SUCRE". Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales. 2012.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Sugar". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "bihargatha.in". Archived from the original on 2011-09-10. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ^ Watson, Andrew. Agricultural innovation in the early Islamic world. Cambridge University Press. p. 26–7.

- ^ There is no evidence from Yemen itself that sugarcane was cultivated in Yemen before the start of the Islamic era. There is plentiful evidence that Yemen imported goods from India in the pre-Islamic era (see e.g. Periplus of the Erythrean Sea). Hence historians today tend to believe that when Dioscorides was writing in the 1st century AD, Yemen imported sugar from India; and, that it did not produce it locally, and that the sugar that Dioscorides obtained in Greece was an import from Yemen but ultimately became an import from India. The Sugar Cane Industry: An Historical Geography from its Origins to 1914, by J.H. Galloway, year 1989, page 24.

- ^ Quoted from Book Two of Dioscorides' Materia Medica. The book is downloadable from links at the Wikipedia Dioscorides page.

- ^ Patrick Faas (2003). Around the Roman Table: Food and Feasting in Ancient Rome. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 149.

- ^ Sato 2014, p. 30.

- ^ "Sugar Cane in Sicily — Best of Sicily Magazine". www.bestofsicily.com. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ Salobreña: Rutas y senderos / Countryside Paths and Walks, ed. by Juan Manuel Pérez, trans. by Deborah Green (Salobreña: Ayuntamiento de Salobreña, 2009), ISBN 8487811132, pp. 9-10.

- ^ Carmen Trillo San José and Gari Amtmann, 'Un castillo junto al río Laroles: ¿Šant Afliy?', AyTM, 8 (2001), 305-23 (p. 309).

- ^ a b Ponting 2000, p. 353.

- ^ Jaine, Tom (1988). Taste: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery. Oxford Symposium on Food & Cookery. p. 16. ISBN 9780907325390. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ a b Ponting 2000, p. 481.

- ^ Barber, Malcolm (2004). The two cities: medieval Europe, 1050–1320 (2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-415-17415-2.

- ^ UMich Middle English Dictionary.

- ^ a b Ponting 2000, p. 482.

- ^ a b c Benitez-Rojo 1996, p. 93.

- ^ Watts 2001.

- ^ Wood 1996, p. 89.

- ^ Von Sivers et al. 2018, p. 574: "The charred animal bones added to the refining, for whitening the crystallizing sugar, were often supplemented by those of deceased enslaved people, thus contributing a particularly sinister element to the process."

- ^ a b c Ponting 2000, p. 510.

- ^ Christer Petley, White Fury (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 20.

- ^ On the Caribbean island of Curaçao, there were slave rebellions in 1716, 1750, 1774, and 1795, the latter led by the slave Tula.

- ^ Wilson 2011.

- ^ Ponting 2000, p. 698.

- ^ Ponting 2000, pp. 698–9.

- ^ Ponting 2000, p. 739.

- ^ "The Origins of Sugar from Beet". EUFIC. 3 July 2001. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Marggraf (1747) "Experiences chimiques faites dans le dessein de tirer un veritable sucre de diverses plantes, qui croissent dans nos contrées" [Chemical experiments made with the intention of extracting real sugar from diverse plants that grow in our lands], Histoire de l'académie royale des sciences et belles-lettres de Berlin, pages 79-90.

- ^ Achard (1799) "Procédé d'extraction du sucre de bette" (Process for extracting sugar from beets), Annales de Chimie, 32 : 163-168.

- ^ Wolff, G. (1953). "Franz Karl Achard, 1753–1821; a contribution of the cultural history of sugar". Medizinische Monatsschrift. 7 (4): 253–4. PMID 13086516.

- ^ "Festveranstaltung zum 100jährigen Bestehen des Berliner Institut für Zuckerindustrie". Technische Universität Berlin. 23 November 2004. Archived from the original on 24 August 2007. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Larousse Gastronomique. Éditions Larousse. 13 October 2009. p. 1152. ISBN 9780600620426.

- ^ "Andreas Sigismund Marggraf | German chemist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Otter, Chris (2020). Diet for a large planet. USA: University of Chicago Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-226-69710-9.

- ^ Otter, Chris (2020). Diet for a large planet. USA: University of Chicago Press. pp. 84–7. ISBN 978-0-226-69710-9.

- ^ Marshall & Kooi 1957.

- ^ Philpott, Tom (10 May 2006). "ADM, high-fructose corn syrup, and ethanol". Grist. Archived from the original on 26 January 2009. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ^ Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Corn--Acreage, Production, and Value, by Leading States statistics - USA Census numbers". www.allcountries.org. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ Bovard, James (April 1998). "The Great Sugar Shaft". Freedom Daily. The Future of Freedom Foundation. Archived from the original on 29 August 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ^ "U.S. per capita food availability – Sugar and sweeteners (individual)". Economic Research Service. 2010-02-16. Archived from the original on 2010-03-06. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- ^ Wosiacki, Gilvan; Nogueira, Alessandro; Denardi, Frederico; Vieira, Renato (1 January 2009). "Sugar composition of depectinized apple juices Composição de açúcares em sucos de maçãs despectinizados". Retrieved 26 January 2018 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Samuel 2011.

- ^ Collino 2011.

Bibliography

- Abbott, Elizabeth (2009) [2008]. Sugar: A Bittersweet History. London and New York: Duckworth Overlook. ISBN 978-0-7156-3878-1.

- Adas, Michael, ed. (2001). Agricultural and Pastoral Societies in Ancient and Classical History. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-56639-832-9.

- Abulafia, David (2011). The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9934-1.

- Benitez-Rojo, Antonio (1996) [1992]. The Repeating Island. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-1865-1.

- Bernstein, William (2009) [2008]. A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN 9781843548034.

- Collino, M (June 2011). "High dietary fructose intake: Sweet or bitter life?". World J Diabetes. 2 (6): 77–81. doi:10.4239/wjd.v2.i6.77. PMC 3158875. PMID 21860690.

- Kieschnick, John (2003). The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture. Princeton: University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09676-6.

- Marshall, RO; Kooi, ER (April 1957). "Enzymatic conversion of D-glucose to D-fructose". Science. 125 (3249): 648–9. Bibcode:1957Sci...125..648M. doi:10.1126/science.125.3249.648. PMID 13421660.

- Mintz, Sidney Wilfred (1986) [1985]. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-009233-2.

- Parker, Matthew (2011). The Sugar Barons: Family, Corruption, Empire and War. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09-192583-3.

- Ponting, Clive (2000). World History: A New Perspective. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-6834-6.

- Samuel, VT (February 2011). "Fructose induced lipogenesis: from sugar to fat to insulin resistance". Trends Endocrinol Metab. 22 (2): 60–65. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2010.10.003. PMID 21067942. S2CID 33205288.

- Sato, Tsugitaka (2014). Sugar in the Social Life of Medieval Islam. BRILL. ISBN 9789004277526.

- Sen, Tansen (2003). Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of Sino-Indian Relations, 600–1400. Manoa: Asian Interactions and Comparisons, a joint publication of the University of Hawaii Press and the Association for Asian Studies. ISBN 978-0-8248-2593-5.

- Sharpe, Peter (1998). Sugar Cane: Past and Present. Illinois: Southern Illinois University. Archived from the original on 2008-05-18.

- Srinivasan, T.M. (2016). "Agricultural Practices as gleaned from the Tamil Literature of the Sangam Age" (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science. 51 (2). doi:10.16943/ijhs/2016/v51i2/48430.

- Von Sivers, Peter; Desnoyers, Charles; Stow, George B.; Perry, Jonathan Scott (2018). Patterns of world history with sources. Vol. 2 (Third ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190693619. LCCN 2017005347.

- Sugar: The Most Evil Molecule from Science History Institute

- Watts, Sheldon J (April 2001). "Yellow Fever Immunities in West Africa and the Americas in the Age of Slavery and Beyond: A Reappraisal". Journal of Social History. 34 (4): 955–967. doi:10.1353/jsh.2001.0071. PMID 17595747. S2CID 31836946.

- Wilson, C Anne (2011) [1985]. The Book of Marmalade. Oakville, CT: David Brown Book Company. ISBN 978-1-903018-77-4.

- Wood, Peter H (1996) [1974]. Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31482-3.