Hollow point bullets

A hollow-point bullet is a type of expanding bullet which expands on impact with a soft target, transferring more or all of the projectile's energy into the target over a shorter distance.

Hollow-point bullets are used for controlled penetration, where overpenetration could cause collateral damage (such as aboard an aircraft). In target shooting, they are used for greater accuracy due to the larger meplat. They are more accurate and predictable compared to pointed bullets which, despite having a higher ballistic coefficient (BC), are more sensitive to bullet harmonic characteristics and wind deflection.

Plastic-tipped bullets are a type of (rifle) bullet meant to confer the aerodynamic advantage of the Spitzer bullet (for example, see very-low-drag bullet) and the stopping power of hollow-point bullets.

History

Solid lead bullets, when cast from a soft alloy, will often deform and provide some expansion if they hit the target at a high velocity. This, combined with the limited velocity and penetration attainable with muzzleloading firearms, meant there was little need for extra expansion.[1]

The first hollow-point bullets were marketed in the late 19th century as express bullets and were hollowed out to reduce the bullet's mass and provide higher velocities. In addition to providing increased velocities, the hollow also turned out to provide significant expansion, especially when the bullets were cast in a soft lead alloy. Originally intended for rifles, the popular .32-20, .38-40, and .44-40 calibers could also be fired in revolvers.[1]

With the advent of smokeless powder, velocities increased, and bullets got smaller, faster, and lighter. These new bullets (especially in rifles) needed to be jacketed to handle the conditions of firing. The new full metal jacket bullets tended to penetrate straight through a target causing less internal damage than a bullet that expands and stops in its target. This led to the development of the soft-point bullet and later jacketed hollow-point bullets at the British arsenal in Dum Dum, near Calcutta around 1890. Designs included the .303" Mk III, IV & V and the .455" Mk III "Manstopper" cartridges. Although such bullet designs were quickly outlawed for use in warfare (in 1898, the Germans complained they breached the Laws of War), they steadily gained ground among hunters due to the ability to control the expansion of the new high velocity cartridges. In modern ammunition, the use of hollow points is primarily limited to handgun ammunition, which tends to operate at much lower velocities than rifle ammunition (on the order of 1,000 feet per second (300 m/s) versus over 2,000 feet per second). At rifle velocities, a hollow point is not needed for reliable expansion and most rifle ammunition makes use of tapered jacket designs to achieve the mushrooming effect. At the lower handgun velocities, hollow point designs are generally the only design that will reliably expand.[1][2]

Modern hollow-point bullet designs use many different methods to provide controlled expansion, including:

- Jackets that are thinner near the front than the rear to allow easy expansion at the beginning, then a reduced expansion rate.

- Partitions in the middle of the bullet core to stop expansion at a given point.

- Bonding the lead core to the copper jacket to prevent separation and fragmentation.

- Fluted or otherwise weakened jackets to encourage expansion or fragmentation.

- Posts in the hollow cavity to cause hydraulic expansion of the bullet in tissue. While very effective in lightly clothed targets, these bullet types tend to plug up with heavy clothing materials that results in the bullet not expanding.

- Solid copper hollow points, which are far stronger than jacketed lead, and provide controlled, uniform expansion even at high velocities.

- Plastic inserts in the hollow, which provide the same profile as a full-metal-jacketed round (such as the Hornady V-Max bullet). The plastic insert initiates the expansion of the bullet by being forced into the hollow cavity upon impact.

- Plastic inserts in the hollow to provide the same profile for feeding in semiautomatic and automatic weapons as a full-metal-jacketed round but that separate on firing while in flight or in the barrel (such as the German Geco "Action Safety" 9 mm round)

Mechanism

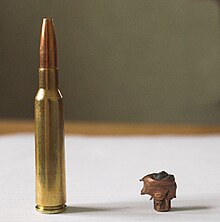

When a hollow-point hunting bullet strikes a soft target, the pressure created in the pit forces the material (usually lead) around the inside edge to expand outwards, increasing the axial diameter of the projectile as it passes through. This process is commonly referred to as mushrooming, because the resulting shape, a widened, rounded nose on top of a cylindrical base, typically resembles a mushroom.

The greater frontal surface area of the expanded bullet limits its depth of penetration into the target and causes more extensive tissue damage along the wound path. Many hollow-point bullets, especially those intended for use at high velocity in centerfire rifles, are jacketed, i.e., a portion of the lead-cored bullet is wrapped in a thin layer of harder metal, such as copper, brass, or mild steel. This jacket provides additional strength to the bullet, increases penetration, and can help prevent it from leaving deposits of lead inside the bore. In controlled expansion bullets, the jacket and other internal design characteristics help to prevent the bullet from breaking apart; a fragmented bullet will not penetrate as far.

Accuracy

Due to their design, hollow point bullets tend to be more accurate than other types of ammunition, as they are less affected by wind resistance and other factors that can affect trajectory.[3] For bullets designed for target shooting, some such as the Sierra "Matchking" incorporate a cavity in the nose, called the meplat. This allows the manufacturer to maintain a greater consistency in tip shape and thus aerodynamic properties among bullets of the same design, at the expense of a slightly decreased ballistic coefficient and higher drag. The result is a slightly decreased overall accuracy between bullet trajectory and barrel direction, as well as an increased susceptibility to wind drift, but closer grouping of subsequent shots due to bullet consistency, often increasing the shooter's perceived accuracy.

The manufacturing process of hollow-point bullets also produces a flat, uniformly shaped base on the bullet which is thought to increase accuracy by providing a more consistent piston surface for the expanding gases of the cartridge.

Testing

Terminal ballistics testing of hollow point bullets are generally performed in ballistic gelatin, or some other medium intended to simulate tissue and cause a hollow point bullet to expand. Test results are generally given in terms of expanded diameter, penetration depth, and weight retention. Expanded diameter is an indication of the size of the wound cavity, penetration depth shows if vital organs could be reached by the bullet, and weight retention indicates how much of the bullet mass fragmented and separated from the main body of the bullet. How these factors are interpreted depends on the intended use of the bullet, and there are no universally agreed-upon ideal metrics.

Legislation

The Hague Convention of 1899, Declaration III, prohibited the use in international warfare of bullets that easily expand or flatten in the body.[4] It is a common misapprehension that hollow-point ammunition is prohibited by the Geneva Conventions, as the prohibition significantly predates those conventions. The Saint Petersburg Declaration of 1868 banned exploding projectiles of less than 400 grams, along with weapons designed to aggravate injured soldiers or make their death inevitable.

Despite the widespread ban on military use, hollow-point bullets are one of the most common types of bullets used by civilians and police,[5] which is due largely to the reduced risk of bystanders being hit by over-penetrating or ricocheted bullets, and the increased speed of incapacitation.[6]

In many jurisdictions, even ones such as the United Kingdom, where expanding and any other kind of ammunition is only allowed to a Firearms certificate holder, it is illegal to hunt certain types of game with ammunition that does not expand.[7][8]

United Kingdom

Most ammunition types, including hollow-point bullets, are only allowed to a section 1 firearms certificate (FAC) holder. The FAC holder must have the calibre in question as a valid allowance on their licence. A valid firearms certificate allows the holder to use ball, full metal jacket, hollow point and ballistic-tipped ammunition for range use and vermin control. A firearms certificate will only be issued to any individual who can provide good reason to the police for the possession of firearms and their ammunition. Until recently[vague] all expanding ammunition fell under section 5 of the Firearms Act 1968 and was only allowed when conditions were entered onto an FAC by the police. This condition would allow expanding ammunition to be used for:[7][9]

- The lawful shooting of deer

- The shooting of vermin or, in the case of carrying on activities in connection with the management of any estate, other wildlife

- The humane killing of animals

- The shooting of animals for the protection of other animals or humans

Some ammunition types are still prohibited under section 5 of the Firearms Act 1968. Ammunition that explodes on impact or any ammunition that is intended for military use are examples of this.

Popular calibres used in the UK for vermin, fox and deer control are as follows: .223 Remington, .243 Winchester, .308 Winchester, .22-250 amongst others, all using hollow-point bullets. Many rimfire calibres also use expanding ammunition such as .22 Long Rifle, .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire and .17 Hornady Magnum Rimfire.

United States

The United States is one of few major powers that did not agree to IV-3 of the Hague Convention of 1899, and thus is able to openly admit to the use of this kind of ammunition in warfare, but the United States ratified the second (1907) Hague Convention IV-23, which says "To employ arms, projectiles, or material calculated to cause unnecessary suffering", similar to IV-3 of the first Convention. For years the United States military respected this Convention and refrained from the use of expanding ammunition, and even made special FMJ .22LR ammunition for use in High Standard pistols that were issued to the OSS agents and the Savage Model 24 .22/.410 combination guns issued in the E series of air crew survival kits. After announcing consideration of using hollow point ammunition for side arms, with a possible start date of 2018,[10] the United States Army began production of M1153 special purpose ammunition for the 9×19mm Parabellum with a 147-grain (9.5 g) jacketed hollow point bullet at 962 feet (293 m) per second for use in situations where limited over-penetration of targets is necessary to reduce collateral damage.[11]

The state of New Jersey bans possession of hollow point bullets by civilians, except for ammunition possessed at one's own dwellings, premises, or other lands owned or possessed, or for, while and traveling to and from hunting with a hunting license if otherwise legal for the particular game. The law also requires all hollow point ammunition to be transported directly from the place of purchase to one's home or premises, or hunting area, or by members of a rifle or pistol club directly to a place of target practice, or directly to an authorized target range from the place of purchase or one's home or premises.[12]

The United States military uses open-tip ammunition in some sniper rifles due to its exceptional accuracy. W. Hays Parks, Colonel, USMC, Chief of the JAG's International Law Branch, has argued that this ammunition is not prohibited by military convention in that the wounds that it produces are similar to full metal jacket ammunition in practice.[13]

Winchester Black Talon scare

In early 1992, Winchester introduced the "Black Talon", a newly designed hollow-point handgun bullet which used a specially designed, reverse tapered jacket. The jacket was cut at the hollow to intentionally weaken it, and these cuts allowed the jacket to open into six petals upon impact. The thick jacket material kept the tips of the jacket from bending as easily as a normal thickness jacket. The slits that weakened the jacket left triangular shapes in the tip of the jacket, and these triangular sections of jacket would end up pointing out after expansion, leading to the "Talon" name. The bullets were coated with a black colored, paint-like lubricant called "Lubalox", and loaded into nickel-plated brass cases, which made them visually stand out from other ammunition. While performance of the Black Talon rounds was not significantly improved over other comparable high-performance hollow-point ammunition, the reverse taper jacket did provide reliable expansion under a wide range of conditions, and many police departments adopted the round.[14]

Winchester's "Black Talon" product name was eventually used against them. After the high-profile 1993 101 California Street shooting in San Francisco, media response against Winchester was swift. "This bullet kills you better", says one report; "its six razorlike claws unfold on impact, expanding to nearly three times the bullet's diameter".[15][16] A concern was raised by the president of the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) that the sharp edges of the jacket could cut medical personnel's skin and risk spread of disease. An ACEP spokesman later said he was not aware of any evidence to support this claim.[17][18]

Winchester responded to the media criticism of the Black Talon line by removing it from the commercial market and only selling it to law enforcement distributors. Winchester has since discontinued the sale of the Black Talon entirely, although Winchester does manufacture nearly identical ammunition under new brand names, the Ranger T-Series and the Supreme Elite Bonded PDX1.[19][20]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Jones, Allan (2016-07-15). "Hollowpoints: Myths & Facts". Shooting Times. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ Association, National Rifle. "An NRA Shooting Sports Journal | Why Are Hollow-Point Rifle Bullets More Accurate?". An NRA Shooting Sports Journal. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ "Hollow Point Bullet - A Guide For First Time Buyers". Bulk Cheap Ammo. Retrieved 2024-09-05.

- ^ "Declaration IV,3 – On the Use of Bullets Which Expand or Flatten Easily in the Human Body". Hague Convention of 1899. 1899-06-29. Archived from the original on 2010-12-18. Retrieved 2010-12-16.

- ^ U.S. Social Security orders 174,000 hollow-point bullets. World – CBC News [1]

- ^ Adkins, Robert; Lindsey, Douglas; Dimaio, Vincent; Marshall, Evan; Fackler, Martin; Peters, Carroll; Goddard, Stan; Smith, O'Brian. "113821NCJRS" (PDF). Office of Justice Programs. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved 2021-08-26.

- ^ a b "Hertfordshire Constabulary Firearms Licensing" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-26. Retrieved 2011-08-03.

- ^ Chuck Hawks. Centerfire Cartridge Fundamentals.[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ "Deer Act 1991", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1991 c. 54

- ^ "Army to consider hollow point bullets for new pistol". Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- ^ Keefe, Mark A. (2019). "M1152 & M1153: The Army's New 9 mm Luger Loads". American Rifleman. 167 (5). National Rifle Association of America: 65. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019.

- ^ "Transportation and use of hollow point ammunition by sportsmen". New Jersey State Police. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- ^ W. Hays Parks, Colonel, USMC, Chief of the JAG's International Law Branch (1985-09-23). "Memorandum: Sniper Use of Open-Tip Ammunition". Archived from the original on 2007-04-27. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

{cite web}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Carter, Gregg Lee (2002). Guns In American Society: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-57607-268-4.

- ^ Petersen, Julie (September 1993). "MotherJones SO93: This bullet kills you better". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on 2007-03-12. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ "Winchester Ranger Talon (Ranger SXT/Black Talon) Wound Ballistics". Tactical Briefs #2. Firearms Tactical Institute. 1998-03-01. Archived from the original on 2008-01-20. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ Hallinan, Joe (1995-01-29). "Black Talon: much ado about little". Newhouse News Service.

- ^ Jeff Chan (1995-03-27). "Letter to CNN". RKBA.org. Archived from the original on 2006-11-14. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ "Winchester Ranger T-Series". Winchester. Archived from the original on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ "Winchester Supreme Elite Bonded PDX1". Winchester. Archived from the original on October 10, 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

External links

- High speed video clips of several Barnes expanding bullets on impact. The 180 grain .308 bullet shows an ideal mushroom shape in the ballistic gelatin, and clearly shows the ripples in the temporary cavity formed by the spinning bullet.

- History of commercial hollow-point bullet molds, going back to the 1890s.

- Premium Rifle Bullets: Who Wins The Toughest Test? Precision Shooter, March, 1996. A comparison test of four different .30-06 hollow-point bullets, showing how performance is measured and compared.

- Hollow bullet with internal structure