House of Hohenlohe

County (Principality) of Hohenlohe Grafschaft (Fürstentum) Hohenlohe | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1450–1806 | |||||||||

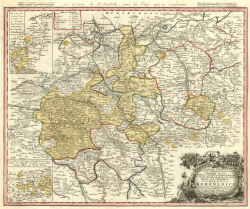

Hohenlohe state, Homann, 1748 | |||||||||

| Status | State of the Holy Roman Empire | ||||||||

| Capital | Öhringen | ||||||||

| Religion | Catholic Lutheran | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Raised to Imperial Counts | 13 May 1450 | ||||||||

• Joined Franconian Circle | 1500 | ||||||||

• Raised to principality | 21 May 1744 | ||||||||

| 12 July 1806 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

The House of Hohenlohe (pronounced [hoːənˈloːə]) is a German princely dynasty. It formerly ruled an immediate territory within the Holy Roman Empire, which was divided between several branches. In 1806, the area of Hohenlohe was 1,760 km² and its estimated population was 108,000.[1] The motto of the house is Ex flammis orior (Latin for 'From flames I rise'). The Lords of Hohenlohe were elevated to the rank of Imperial Counts in 1450, and from 1744, the territory and its rulers were princely. In 1825, the German Confederation recognized the right of all members of the house to be styled as Serene Highness (German: Durchlaucht), with the title of Fürst for the heads of its branches, and the title of prince/princess for the other members.[2] From 1861, the Hohenlohe-Öhringen branch was also of ducal status as dukes of Ujest.

Due to the continuous lineage of the dynasty until the present time, it is considered to be one of the longest-lived noble families in Germany and Europe. The large state coat of arms of Baden-Württemberg today bears the Frankish rake of the former Duchy of East and West Franconia, which also included the Franconian region of Baden-Württemberg around Heilbronn-Hohenlohe. The dynasty is related to the Staufers around the famous Emperor Barbarossa, and also to the British royal family through Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, Princess Alexandra of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and Queen Victoria's half-sister Princess Feodora of Leiningen.

History

The first ancestor was mentioned in 1153 as Conrad, Lord of Weikersheim, where the family had the Geleitrecht (right of escorting travellers and goods and charging customs) along the Tauber river on the trading route between Frankfurt and Augsburg until the 14th century. It is likely that Conrad was a son of Conrad von Pfitzingen, who was already mentioned in documents in 1136/1141 and owned a castle of that name near Weikersheim. Allegedly, according to some, however unconfirmed sources, the wife of Conrad von Pfitzingen named Sophie was an illegitimate daughter of Conrad III Hohenstaufen, King of Germany, with a noble lady named Gerberga.[3] The Hohenlohe family therefore later boasted of a kinship with the Imperial House of Hohenstaufen.

Heinrich von Weikersheim is mentioned in documents from 1156 to 1182 and Adelbert von Weikersheim around 1172 to 1182. The latter used Hohenlohe ("Albertus de Hohenloch") as his name for the first time in 1178 which is derived from the no longer existing Hohlach Castle near Simmershofen in Middle Franconia. His brother Heinrich also called himself so from 1182 (in the versions “Hohenlach” or “Holach”) which later was to become Hohenlohe. The name means “high-lying wood” (high Loh). The name Hohenlohe was probably adopted because Weikersheim was a fiefdom of the Comburg monastery, but Hohlach was an imperial fiefdom that granted its owners the status of imperial knight. Hohlach Castle secured the Rothenburg−Ochsenfurt road. However, Hohlach soon lost its importance; the family's holdings were expanded from Weikersheim, which is located about 20 km further west, southwards to form the county of Hohenlohe. Haltenbergstetten Castle near Pfitzingen, south of Weikersheim, was built around 1200, as was Brauneck Castle halfway between Weikersheim and Hohlach.

The dynasty's influence was soon perceptible between the Franconian valleys of the Kocher, Jagst and Tauber rivers, an area that was to be called the Hohenlohe Plateau.[4] Their original main seats were Weikersheim, Hohlach and Brauneck (near Creglingen).

-

Brauneck Castle

Of Konrad von Weikersheim's three sons, Konrad and Albrecht died childless. Heinrich I von Hohenlohe, the third son, died around 1183; he had five sons, of whom Andreas, Heinrich and Friedrich entered the Teutonic Order and thus the clergy, as a result of which the House of Hohenlohe lost important possessions around Mergentheim to the order. Like Hohlach Castle, these had probably fallen to the Lords of Weikersheim through marriage. In 1219 Mergentheim became the seat of the Mergentheim Commandery. Mergentheim Palace became the residence of the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order in 1527 and remained the headquarters of the Order until 1809.

The son Heinrich von Hohenlohe (d. 1249) became Grand Master of the Teutonic Order. His grandsons, Gottfried and Conrad, supporters of Emperor Frederick II, founded the lines of Hohenlohe-Hohenlohe and Hohenlohe-Brauneck in 1230, the names taken from their respective castles.[5] The emperor granted them the Italian counties of Molise and Romagna in 1229/30, but they were not able to hold them for long. Gottfried was a tutor and close advisor to the emperor's son king Conrad IV. When the latter survived an assassination attempt plotted by bishop Albert of Regensburg, he granted Gottfried some possessions of the Prince-Bishopric of Regensburg, namely the Vogt position for the Augustine Stift at Öhringen and the towns of Neuenstein and Waldenburg. Gottfried's son Kraft I acquired the town of Ingelfingen with Lichteneck Castle. In 1253 the town and castle of Langenburg were inherited by the lords of Hohenlohe, after the lords of Langenburg had become extinct. During the Interregnum the Hohenlohe sided with the Prince-Bishopric of Würzburg and defeated the count of Henneberg and his coalition at the Battle of Kitzingen gaining Uffenheim in the aftermath. In 1273 Kraft of Hohenlohe fought at the Battle on the Marchfeld on the side of king Rudolf of Habsburg. By 1300, town and castle Schillingsfürst had also passed into the possession of the Hohenlohe lords.

Hohlach later became part of the Principality of Ansbach, a subsequent state of the Hohenzollern Burgraviate of Nuremberg, to which the Hohenlohe family had sold the nearby town of Uffenheim in 1378,[6] and Hohlach some time later. Yet, the name Hohenlohe remained attached to the county with its other territories.

The branch of Hohenlohe-Brauneck received Jagstberg Castle (near Mulfingen) as af fief from the Bishop of Würzburg around 1300, which later came to various other feudal holders, but repeatedly also back to the House of Hohenlohe. The Lords of Hohenlohe-Brauneck became extinct in 1390, their lands were sold to the Hohenzollern margraves of Ansbach in 1448. Hohenlohe-Hohenlohe was divided into several branches, two of which were Hohenlohe-Weikersheim and Hohenlohe-Uffenheim-Speckfeld (1330–1412). Hohenlohe-Weikersheim, descended from count Kraft I (died 1313), also underwent several divisions, the most important following the deaths of counts Albert and George in 1551. At this time the two main branches of Hohenlohe-Neuenstein and Hohenlohe-Waldenburg were founded by George's sons. Meanwhile, in 1412, the branch of Hohenlohe-Uffenheim-Speckfeld had become extinct, and its lands passed to other families by marriage.[5] George Hohenlohe was prince-bishop of Passau (1390–1423) and archbishop of Esztergom (1418–1423), serving King Sigismund of Hungary (the later King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor).

In 1450, Emperor Frederick III granted Kraft of Hohenlohe (died 1472) and his brother, Albrecht, the sons of Elizabeth of Hanau, heiress of Ziegenhain, the title Count of Ziegenhain (Graf zu Ziegenhain) and invested them with the County of Ziegenhain.[7] Actually, the Landgraves of Hesse soon took the County of Ziegenhain. After decades of, sometimes armed, conflict, the Hohenlohe gave up their claim to Ziegenhain in favor of the Hessian landgrave in a settlement with financial compensation in 1495. In this context, the emperor elevated their lordship Hohenlohe to the status of an imperial county. The county remained divided between several family branches, however still being an undivided Imperial Fief under the imperial jurisdiction, and was to be represented by the family's senior vis-à-vis the imperial court.

The Hohenlohes were Imperial Counts having two voices in the Diet (or Assembly, called Kreistag) of the Franconian Circle.[8] They also had six voices in the Franconian College of Imperial Counts (Fränkisches Reichsgrafenkollegium) of the Imperial Diet (Reichstag).[9] The right to vote in the Imperial Diet gave a German noble family the status of imperial state (Reichsstände) and made them belong to the High Nobility (Hoher Adel), on a par with ruling princes and dukes.

By 1455, Albrecht of Hohenlohe had acquired the castle and lordship of Bartenstein (near Schrozberg). In 1472 the town and castle of Pfedelbach were bought by the Hohenlohe family. In 1586, Weikersheim was inherited by count Wolfgang who reconstructed the medieval Weikersheim Castle into a Renaissance palace. When the last Weikersheim count, Carl Ludwig, died around 1760, his lands were divided between the Langenburg, Neuenstein and Öhringen branches; in 1967, Prince Constantin of Hohenlohe-Langenburg sold Weikersheim Castle, meanwhile a museum, to the state.

The existing branches of the Hohenlohe family are descended from the lines of Hohenlohe-Neuenstein and Hohenlohe-Waldenburg, established in 1551 by Ludwig Kasimir (d. 1568) and Eberhard (d. 1570), the sons of Count Georg I (d. 1551).[10] Since Georg had become protestant on his deathbed, the reformation was introduced in the county and confirmed by the Peace of Augsburg in 1556. In 1667 however, a confessional division arose when the two sons of Georg Friedrich II of Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst, Christian (founder of the Bartenstein line) and Ludwig Gustav (founder of the Schillingsfürst line), converted to the Catholic Church. After the extinction of two other protestant side lines, Waldenburg in 1679 and Waldenburg-Pfedelbach in 1728, the whole property of the main branch Hohenlohe-Waldenburg was inherited by the catholic counts.

Of the Lutheran branch of Hohenlohe-Neuenstein, which underwent several partitions and inherited the county of Gleichen in Thuringia (with its residence at Ehrenstein Castle in Ohrdruf) in 1631, the senior line became extinct in 1805, while in 1701 the junior line divided itself into three branches, those of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen and Hohenlohe-Kirchberg.[5] The branch of Kirchberg died out in 1861, with its lands and castle passing to the Öhringen-Neuenstein branch (Kirchberg Castle was sold in 1952), but the branches of Hohenlohe-Langenburg (residing at Langenburg Castle) and Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen still exist, the latter being divided into Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen-Öhringen (which became extinct in 1960) and Hohenlohe-Oehringen (today residing at Neuenstein Castle). The two actual heads of the branches of Langenburg and Oehringen are traditionally styled Fürst. The two princes of Hohenlohe-Oehringen-Neuenstein and of Hohenlohe-Langenburg entertained a government office for the county of Gleichen at Ehrenstein Castle until 1848.

Frederick Louis, Prince of Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen, had acquired the estates of Slawentzitz, Ujest and Bitschin in Silesia by marriage in 1782, an area of 108 square miles, where his grandson Hugo zu Hohenlohe-Öhringen, Duke of Ujest, established calamine mines and founded one of the largest zinc smelting plants in the world. His son, prince Christian Kraft (1848–1926), sold the plants and went almost bankrupt with a fund in which he had invested in 1913; the mines he had still kept were depropriated by communist Poland in 1945. Until then, this branch had its headquarters in Slawentzitz and also owned estates in Hungary. After their expulsion and expropriation, the branch returned to Neuenstein.

The Catholic branch of Hohenlohe-Waldenburg was soon divided into three side branches, but two of these had died out by 1729. The surviving branch, that of Schillingsfürst, was divided into the lines of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst and Hohenlohe-Bartenstein, with further divisions following.[5] The four catholic lines which still exist today (with their heads styled Fürst) are those of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst (at Schillingsfürst), Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst (at Waldenburg), Hohenlohe-Jagstberg (at Haltenbergstetten) and Hohenlohe-Bartenstein (at Bartenstein). A side branch of the House of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst inherited the dukedom of Ratibor in Silesia in 1834, together with the principality of Corvey in Westphalia. While the Silesian property was expropriated in Poland in 1945, Corvey Abbey remains owned by the Duke of Ratibor to this day, together with further inherited properties in Austria.

The Holy Roman Emperors granted the title of Imperial Prince (Reichsfürst) to the Waldenburg line (in 1744) and to the Neuenstein (Öhringen) line (in 1764).[11] In 1757, the Holy Roman Emperor elevated possessions of the Waldenburg line to the status of Imperial Principality.[12] In 1772, the Holy Roman Emperor elevated possessions of the Neuenstein and Langenburg lines to the status of Imperial Principality.[12]

On 12 July 1806, the principalities became parts of the kingdoms of Bavaria and of Württemberg by the Act of the Confederation of the Rhine. Therefore, the region of Hohenlohe is presently located for the most part in the north eastern part of the State of Baden-Württemberg (forming the counties of Hohenlohe, Schwäbisch Hall and the southern part of Main-Tauber-Kreis), with smaller parts in the Bavarian administrative districts of Middle Franconia and Lower Franconia. The Hohenlohisch dialect is part of the East Franconian German dialect group and the population still values its traditional distinct identity.

Family members

Notable members of the von Hohenlohe family include:

- Heinrich von Hohenlohe, 13th-century Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights

- Gottfried von Hohenlohe, 14th-century Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights

- Frederick Louis, Prince of Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen (1746–1818), Prussian general

- Louis Aloy de Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Bartenstein (1765–1829), marshal and peer of France

- August, Prince of Hohenlohe-Öhringen (1784–1853), general

- Prince Alexander of Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst (1794–1849), priest

- Hugo zu Hohenlohe-Öhringen (1816–1897), Prussian industrialist and general

- Victor I, Duke of Ratibor, Prince of Corvey, Prince of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst (1818–1893)

- Prince Chlodwig zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst (1819–1901), Chancellor of Germany

- Gustav Adolf Hohenlohe (1823–1896), a Catholic cardinal

- Kraft, Prinz zu Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen (1827–1892), Prussian general and writer

- Hans zu Hohenlohe-Öhringen (1858–1945), a Prussian diplomat

- Prince Konrad of Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst (1863–1918), Austrian statesman and aristocrat

- Friedrich Franz, Prince von Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst (1879–1958), Austrian military attache and later German spy-master. His first wife, Stephanie von Hohenlohe (1891–1972), was a German spy in the 1930s and at the start of WWII.

- Gottfried, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg (1897–1960), husband of Princess Margarita of Greece and Denmark (1905–1981), the sister of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

- Alfonso, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg (1924–2003), founder of Marbella Club, Spain

- Hubertus, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg (b. 1959), competitive skier, singer, music producer

- Philipp, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg (b. 1970), grandson of Gottfried, owner of Langenburg Castle

- Princess Victoria of Hohenlohe-Langenburg (b. 1997), 20th Duchess of Medinaceli etc, Grandee of Spain, who is, with 43 titles, the most titled person in the world[13]

-

Prince Chlodwig zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst (1819–1901), Chancellor of the German Empire (1894–1900)

-

Prince Konrad of Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst (1863–1918), Prime Minister of Austria (1906)

Castles of the House of Hohenlohe

(*) still owned by members of the House of Hohenlohe

-

Langenburg Castle*

-

Öhringen Castle

-

Waldenburg town and castle*

-

Schillingsfürst Castle*

-

Bartenstein Castle* near Schrozberg

-

Ingelfingen Castle

-

Pfedelbach Castle

-

Haltenbergstetten Castle*

-

Kirchberg Castle

-

Ehrenstein Castle at Ohrdruf, Thuringia (County of Gleichen)

-

The palace monastery of Rudy (German: Schloss Rauden) near Ratibor, Silesia (Poland)

-

Imperial Abbey of Corvey*, Westfalia

-

Schloss Grafenegg*, Lower Austria

-

Neuaigen Castle*, Lower Austria

-

Sławięcice Palace (Schloss Slawentzitz), Silesia (Poland) (now demolished)

-

Oppurg Castle, Thuringia

-

El Quexigal, Spain

Heads of existing branches

Neuenstein line (Lutheran)

- Hohenlohe-Langenburg branch: Philipp, 10th Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, Count of Gleichen (born 1970), at Langenburg castle

- Hohenlohe-Oehringen branch: Kraft, 9th Prince of Hohenlohe-Oehringen, 5th Duke of Ujest, Count of Gleichen (born 1933), at Neuenstein castle

Waldenburg line (Catholic)

- Hohenlohe-Bartenstein branch: Maximilian, 10th Prince of Hohenlohe-Bartenstein, (born 1972), at Bartenstein castle

- Hohenlohe-Jagstberg branch: Alexander, 2nd Prince of Hohenlohe-Jagstberg (born 1937), at Haltenbergstetten castle

- Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst branch: Felix, 10th Prince of Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst (born 1963), at Waldenburg castle

- Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst branch: Constantin, 12th Prince of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst (born 1949), at Schillingsfürst castle

- Ratibor and Corvey branch: Viktor, 5th Duke of Ratibor and 5th Prince of Corvey, Prince of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst-Metternich-Sándor (b. 1964), owner of the Imperial Abbey of Corvey, Germany, and Grafenegg and Neuaigen Castles, Lower Austria

Legion de Hohenlohe

The Legion de Hohenlohe was a unit of foreign soldiers serving in the French Army until 1831, when its members (as well as those of the disbanded Swiss Guards) were folded into the newly-raised French Foreign Legion for service in Algeria.

Notes

- ^ "Map of Baden-Wurttemberg 1789 - Northern Part". hoeckmann.de.

- ^ Almanach de Gotha: 1910, pages 140-148.

- ^ Tobias Weller: Die Heiratspolitik des deutschen Hochadels im 12. Jahrhundert (The marriage policy of the German nobility in the 12th century). Böhlau, Cologne 2004, pp. 211–220. According to Hansmartin Decker-Hauff, based on the sources of the Imperial Abbey of Lorch he used, there should have been a close relationship between the House of Hohenlohe and the House of Hohenstaufen. However, according to more recent research, these details cannot be proven beyond doubt according to historian Klaus Graf: Staufer-Überlieferungen aus Kloster Lorch (Traditions of the Hohenstaufen from Lorch Monastery), in: Sönke Lorenz et al. (Ed.): Von Schwaben bis Jerusalem. Facetten staufischer Geschichte. Sigmaringen (From Swabia to Jerusalem. Facets of Staufer history). Sigmaringen 1995, pp. 209–240. See also: "Hohenlohe 1".

- ^ Europäische Stammtafeln. Neue Folge, Band XVII (1998), table # 1

- ^ a b c d Phillips & Atkinson 1911, p. 572.

- ^ Stokvis. Manuel d'histoire, de généalogie et de chronologie (Leiden 1887–1893): tome III, pages 354–356.

- ^ Europäische Stammtafeln. Neue Folge, Band XVII (1998), table # 3; Almanach de Gotha, 1941, page 216.

- ^ Berghaus. Deutschland seit hundert Jahren (Leipzig 1859–1862): Abtheilung I, Band I, page 165.

- ^ Lancizolle. Uebersicht der deutschen Reichsstandschafts- und Territorial-Verhältnisse (Berlin 1830): page 8, 46

- ^ Europäische Stammtafeln. Neue Folge, Band XVII (1998), tables # 4,6,15

- ^ Frank. Standeserhebungen und Gnadenakte für das Deutsche Reich und die österreichischen Erblande (Senftenegg 1967–1974): Band 2, page 221

- ^ a b Frank. Standeserhebungen und Gnadenakte für das Deutsche Reich und die österreichischen Erblande (Senftenegg 1967–1974): Band 2, page 221.

- ^ "Victoria de Hohenlohe, la joven con más títulos nobiliarios de España". abc (in Spanish). 2017-10-15. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

References

- Genealogy of the House of Hohenlohe

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Phillips, Walter Alison; Atkinson, Charles Francis (1911). "Hohenlohe". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). pp. 572–575.

- See generally A. F. Fischer, Geschichte des Hauses Hohenlohe (1866–1871),

- K. Weller, Hohenlohisches Urkundenbuch. 1153–1350 (Stuttgart, 1899–1901), and

- Geschichte des Hauses Hohenlohe (Stuttgart, 1904). (W. A. P.; C. F. A.)

- Alessandro Cont, La Chiesa dei principi. Le relazioni tra Reichskirche, dinastie sovrane tedesche e stati italiani (1688–1763). Preface of Elisabeth Garms-Cornides, Trento, Provincia autonoma di Trento, 2018, pp. 152–156.

External links

- The House of Hohenlohe

- European Heraldry page Archived 2020-10-24 at the Wayback Machine