Industrial complex

| Part of the behavioral sciences |

| Economics |

|---|

|

The industrial complex is a socioeconomic concept wherein businesses become entwined in social or political systems or institutions, creating or bolstering a profit economy from these systems. Such a complex is said to pursue its own interests regardless of, and often at the expense of, the best interests of society and individuals. Businesses within an industrial complex may have been created to advance a social or political goal, but mostly profit when the goal is not reached. The industrial complex may profit financially, or ideologically, from maintaining socially detrimental or inefficient systems.

History

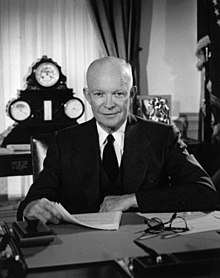

The concept was popularized by President Dwight Eisenhower[1] in his Jan. 17, 1961 farewell speech. Eisenhower described a "threat to democratic government"[1] called the military–industrial complex. This complex involved the military establishment gaining "unwarranted influence" over the economic, political, and spiritual realms of American society due to the profitability of the US arms industry and the number of citizens employed in various branches of military service, the armaments industry, and other businesses providing goods to the US army. The "complex" arises from the creation of a multilateral economy serving military goals, as well as the paradox that arises from the goal of the multilateralism (sustained profit) as antithetical to the military's theoretical goal (peace).

Operations

In many cases, the industrial complex refers to a conflict of interest between an institution's purported socio-political purpose and the financial interests of the businesses and government agencies that profit from the pursuit of such purpose, when achieving the stated purpose would result in a financial loss for those businesses. For example, the purported purpose of the US penal system is to assist offenders in becoming law abiding citizens[2] yet the prison–industrial complex subsists upon high inmate populations, thus relying on the penal system's failure to meet its goal of criminal reform and re-entry. In these types of cases, government agencies are often thought to profit financially from institutional industrialization, perhaps eroding their motivation to legislate such institutions in ways that may be socially beneficial.

The industrial complex concept has also been used informally to denote the artificial creation, inflation, or manipulation of an institution's societal value in order to increase profit opportunities, especially through specialty businesses and niche products. An example of this is the marriage industrial complex,[3][4][5][6] where demand for wedding dress makers, wedding venues, wedding planners, wedding cake bakers, wedding rentals companies, wedding photographers, etc, is created by the perceived social necessity of an elaborate wedding ceremony.[7]

Examples

- Military–Industrial Complex — Businesses that supply the army with uniforms, artillery, etc, profit from the continuation of war and will be hurt by peace.[8]

- Animal–Industrial Complex — Systematic and institutionalized exploitation of non-human animals, which requires breeding and killing animals in the billions in what has come to be known as the "animal holocaust",[9][10]: 29–32, 97 [11] threatening human survival[12]: 299 and resulting in environmental destruction such as climate change,[13] ocean acidification,[13] biodiversity loss,[13] spread of zoonotic diseases,[14]: 198 [15][16] and the sixth mass extinction.[17]

- Prison–Industrial Complex — Businesses access labor from prisoners that is cheaper than civilian labor, thus they profit from high incarceration rates.[18]

- Medical–Industrial Complex — Hospitals and pharmaceutical companies require patients to be sick, thus business interests are at odds with the goal of making people healthy.[19] Inflation of drug and hospital prices contribute to the rising expense of healthcare in the United States.[20][21]

- Wedding/Marriage–Industrial Complex — Wedding-related businesses and vendors profit from the growing extravagance and cost of weddings and will be negatively impacted by smaller, cheaper events or elopements, thus they perpetuate the pressure on brides to have expensive weddings.[22]

- (Hot) Take-Industrial Complex – Professional commentators need to express novel opinions (known as "hot takes") to differentiate themselves and capture audience attention, which leads to increasingly fringe ideas becoming the most prominent in the public discourse.[23][24]

- Non-profit industrial complex, or "NPIC", is a term which is used by social justice activists to describe the way non-profit organizations, governments, and businesses are related. The academic genealogy of the term follows the lineage of what social justice activists and scholars such as Angela Davis and Mike Davis (no relation) have called the Prison-Industrial Complex, which, too, follows an earlier critique of the military-industrial complex. Many activists carry out their work as employees of or with the assistance of non-profit organizations. Many of their goals need money in order to be achieved, and nonprofits are registered with the government in order to be allowed to receive large amounts of money legally. These activist nonprofits usually get money from even bigger nonprofits, which are connected to big businesses and rich people who control industries. But because many activists criticize things in society that businesses and rich people support, they might not get the money if they are too critical. So in order to stay funded, they may have to change the ideas they have for improving society to be more acceptable to industry. People who believe these kinds of relationships between activists and industries are harmful to activism use the term non-profit industrial complex as a faster way to discuss these relationships, instead of explaining the whole system each time. They have written many articles and books describing the effects of the NPIC by studying patterns of funding or discussing how the goals of some activists changed once their movements began to receive more money.[25][26]

Applications

The following have been considered examples of industrial complexes:

- Academic–industrial complex[27][28][29][30]

- Animal–industrial complex[31]

- Athletic–industrial complex

- Baby or diaper–industrial complex[32][33][34]

- Celebrity–industrial complex

- Global–industrial complex[35]

- Immigration–industrial complex[36][37][38] or border–industrial complex[39][40]

- Medical–industrial complex[41] or medical–pharmacological industrial complex

- Military–industrial complex

- Nonprofit–industrial complex[43] or NGO–industrial complex[44]

- Peace–industrial complex

- Pharmaceutical–industrial complex

- Politico-media complex

- Poverty industrial complex

- Prison–industrial complex[45] or criminal (justice) industrial complex[46]

- White savior industrial complex[47]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Ike's Warning Of Military Expansion, 50 Years Later". NPR.org. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- ^ "Organization, Mission and Functions Manual: Federal Bureau of Prisons". www.justice.gov. 2014-08-27. Archived from the original on 2019-05-25. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- ^ "What the Wedding Industrial Complex Is – And How It's Hurting Our Ideas of Love". Everyday Feminism. 2017-04-13. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- ^ "The wedding industrial complex". theweek.com. 2013-06-15. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- ^ Escobar, Natalie (2019-02-11). "The Wedding-Industry Bonanza, on Full Display". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- ^ Garber, Megan (2017-07-20). "How 'I Do' Became Performance Art". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- ^ "The Dark Side Of The Disney Princess Fantasy". HuffPost. 2012-06-29. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- ^ "Military-Industrial Complex". HISTORY. 21 August 2018. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- ^ Benatar, David (2015). "The Misanthropic Argument for Anti-natalism". In S. Hannan; S. Brennan; R. Vernon (eds.). Permissible Progeny?: The Morality of Procreation and Parenting. Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0199378128.

- ^ Best, Steven (2014). The Politics of Total Liberation: Revolution for the 21st Century. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137471116.

- ^ Hedges, Chris (August 3, 2015). "A Haven From the Animal Holocaust". Truthdig. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ Sorenson, John (2014). Critical Animal Studies: Thinking the Unthinkable. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Scholars' Press. ISBN 978-1-55130-563-9. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ^ a b c Steinfeld, Henning; Gerber, Pierre; Wassenaar, Tom; Castel, Vincent; Rosales, Mauricio; de Haan, Cees (2006), Livestock's Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options (PDF), Rome: FAO

- ^ Nibert, David (2011). "Origins and Consequences of the Animal Industrial Complex". In Steven Best; Richard Kahn; Anthony J. Nocella II; Peter McLaren (eds.). The Global Industrial Complex: Systems of Domination. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 197–209. ISBN 978-0739136980.

- ^ Beirne, Piers (May 2021). "Wildlife Trade and COVID-19: Towards a Criminology of Anthropogenic Pathogen Spillover". The British Journal of Criminology. 61 (3). Oxford University Press: 607–626. doi:10.1093/bjc/azaa084. ISSN 1464-3529. PMC 7953978. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ Adams, Carol J. (1997). ""Mad Cow" Disease and the Animal Industrial Complex: An Ecofeminist Analysis". Organization & Environment. 10 (1). SAGE Publications: 26–51. doi:10.1177/0921810697101007. JSTOR 26161653. S2CID 73275679. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Ripple WJ, Wolf C, Newsome TM, Galetti M, Alamgir M, Crist E, Mahmoud MI, Laurance WF (13 November 2017). "World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice" (PDF). BioScience. 67 (12): 1026–1028. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix125. hdl:11336/71342. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

Moreover, we have unleashed a mass extinction event, the sixth in roughly 540 million years, wherein many current life forms could be annihilated or at least committed to extinction by the end of this century.

- ^ "Justice in America Episode 26: The Privatization of Prisons". The Appeal. April 2020. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- ^ Relman, Arnold S. (23 October 1980). "The New Medical-Industrial Complex". New England Journal of Medicine. 303 (17): 963–970. doi:10.1056/NEJM198010233031703. PMID 7412851.

- ^ Wohl, Stanley. The Medical Industrial Complex / Stanley Wohl. First edition. New York: Harmony Book, 1984: 85-98

- ^ Lexchin J, Grootendorst P. Effects of Prescription Drug User Fees on Drug and Health Services Use and on Health Status in Vulnerable Populations: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. International Journal of Health Services. 2004;34(1):101-122. doi:10.2190/4M3E-L0YF-W1TD-EKG0

- ^ "The wedding industrial complex". theweek.com. 2013-06-15. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- ^ Stockton, Nick. "The 19th Century Argument for a 21st Century Space Force". Wired. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Serazio, Michael (2 November 2019). "Deadspin died just like it lived. The sports world will be worse off without it". Washington Post. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Incite! Women of Color Against Violence, ed. (2017). The revolution will not be funded: beyond the non-profit industrial complex. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-6380-4.

- ^ "The Political Logic of the Non-Profit Industrial Complex, 21", The Revolution Will Not Be Funded, Duke University Press, pp. 21–40, 2020-12-31, doi:10.1515/9780822373001-004, ISBN 978-0-8223-7300-1, retrieved 2024-04-23

- ^ Nocella II, Anthony J.; Best, Steven; McLaren, Peter, eds. (2010). Academic Repression: Reflections from the Academic Industrial Complex. AK Press. ISBN 978-1904859987.

- ^ Lee, Felicia R. (2003-09-06). "Academic Industrial Complex". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- ^ Gandio, Jason Del (12 August 2010). ""Neoliberalism and the Academic-Industrial Complex"". Truthout. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- ^ Smith, Andrea (October 2007). "Social-Justice Activism in the Academic Industrial Complex". Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion. 23 (2): 140–145. doi:10.2979/FSR.2007.23.2.140. S2CID 144483113.

- ^ Nibert, David (2011). "Origins and Consequences of the Animal Industrial Complex". In Steven Best; Richard Kahn; Anthony J. Nocella II; Peter McLaren (eds.). The Global Industrial Complex: Systems of Domination. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 197–209. ISBN 978-0739136980.

- ^ "10 Essential Diaper Changing Tips For New Parents". HuffPost. 2018-01-25. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- ^ Chopra, Samir (2013-09-13). "The Baby Industrial Complex". Samir Chopra. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- ^ "China Leads the Way in Diapers". Nonwovens Industry Magazine - News, Markets & Analysis for the Nonwovens Industry. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- ^ Steven Best; Richard Kahn; Anthony J. Nocella II; Peter McLaren, eds. (2011). The Global Industrial Complex: Systems of Domination. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0739136980.

- ^ Feldman, David B. (2022). "Between Exploitation and Repression: The Immigration Industrial Complex and Militarized Migration Management". Marxism and Migration. Marx, Engels, and Marxisms. Springer International Publishing. pp. 231–261. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-98839-5_10. ISBN 978-3-030-98839-5.

- ^ Trujillo-Pagán, Nicole (January 2014). "Emphasizing the 'Complex' in the 'Immigration Industrial Complex'". Critical Sociology. 40 (1): 29–46. doi:10.1177/0896920512469888.

- ^ Golash-Boza, Tanya (March 2009). "The Immigration Industrial Complex: Why We Enforce Immigration Policies Destined to Fail". Sociology Compass. 3 (2): 295–309. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00193.x.

- ^ Pérez, Cristina Jo (2022). "Performing the State's Desire: The Border Industrial Complex and the Murder of Anastasio Hernández Rojas". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 43 (1): 93–119. doi:10.1353/fro.2022.0003. S2CID 246648168.

- ^ Smith, Cameron (2019). "'Authoritarian neoliberalism' and the Australian border-industrial complex". Competition & Change. 23 (2): 192–217. doi:10.1177/1024529418807074. S2CID 158983931.

- ^ Ismail, Asif (2011). "Bad For Your Health: The U.S. Medical Industrial Complex Goes Global". In Steven Best; Richard Kahn; Anthony J. Nocella II; Peter McLaren (eds.). The Global Industrial Complex: Systems of Domination. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 211–232. ISBN 978-0739136980.

- ^ Miller, Toby (2011). "The Media-Military Industrial Complex". In Steven Best; Richard Kahn; Anthony J. Nocella II; Peter McLaren (eds.). The Global Industrial Complex: Systems of Domination. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 97–115. ISBN 978-0739136980.

- ^ "Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex". INCITE!. 2018-08-01. Retrieved 2020-01-29.

- ^ Gereffi, Gary; Garcia-Johnson, Ronie; Sasser, Erika (2001). "The NGO-Industrial Complex". Foreign Policy (125): 56–65. doi:10.2307/3183327. JSTOR 3183327 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ "What is the PIC? What is Abolition? – Critical Resistance". Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- ^ Nagel, Mechthild (2011). "The Criminal (Justice) Industrial Complex". In Steven Best; Richard Kahn; Anthony J. Nocella II; Peter McLaren (eds.). The Global Industrial Complex: Systems of Domination. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 117–131. ISBN 978-0739136980.

- ^ Cole, Teju (21 March 2012). "The White-Savior Industrial Complex". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2023-05-20.