Intersex in history

| Intersex topics |

|---|

|

Intersex, in humans and other animals, describes variations in sex characteristics including chromosomes, gonads, sex hormones, or genitals that, according to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies".[1][2][page needed] Intersex people were historically termed hermaphrodites, "congenital eunuchs",[3][4] or even congenitally "frigid".[5][page needed] Such terms have fallen out of favor, now considered to be misleading and stigmatizing.[6]

Intersex people have been treated in different ways by different cultures. Whether or not they were socially tolerated or accepted by any particular culture, the existence of intersex people was known to many ancient and pre-modern cultures and legal systems, and numerous historical accounts exist.

Ancient history

Sumer

A Sumerian creation myth from more than 4,000 years ago has Ninmah, a mother goddess, fashioning humanity out of clay.[7] She boasts that she will determine the fate – good or bad – for all she fashions:

Enki answered Ninmah: "I will counterbalance whatever fate – good or bad – you happen to decide.

Ninmah took clay from the top of the abzu [ab: water; zu: far] in her hand and she fashioned from it first a man who could not bend his outstretched weak hands. Enki looked at the man who cannot bend his outstretched weak hands, and decreed his fate: he appointed him as a servant of the king. (Three men and one woman with atypical biology are formed and Enki gives each of them various forms of status to ensure respect for their uniqueness)

...Sixth, she fashioned one with neither penis nor vagina on its body. Enki looked at the one with neither penis nor vagina on its body and gave it the name Nibru (eunuch(?)), and decreed as its fate to stand before the king.[7]

Ancient Judaism

In traditional Jewish culture, intersex individuals were either androgynos or tumtum and took on different gender roles, sometimes conforming to men's, sometimes to women's.[further explanation needed]

Ancient Indian Subcontinent

The Tirumantiram Tirumular recorded the relationship between intersex people and Shiva.[8][further explanation needed]

Ardhanarishvara, an androgynous composite form of male deity Shiva and female deity Parvati, originated in Kushan culture as far back as the first century CE.[9][page needed] A statue depicting Ardhanarishvara is included in India's Meenkashi Temple; this statue clearly shows both male and female bodily elements.[10]

Due to the presence of intersex traits, Ardhanarishvara is associated with the hijra,[11][page needed] a third sex category that has been accepted in South Asia for centuries.[11][page needed] After interviewing and studying the hijra for many years, Serena Nanda writes in her book Neither Man Nor Woman: The Hijras of India as follows: "There is a widespread belief in India that hijras are born hermaphrodites [intersex] and are taken away by the hijra community at birth or in childhood, but I found no evidence to support this belief among the hijras I met, all of whom joined the community voluntarily, often in their teens."[12][page needed]

According to Gilbert Herdt, the hijra differentiate between "born" and "made" individuals, or those who have physical intersex traits by birth and those who become hijra through penectomy, respectively.[11][page needed] According to Indian tradition, the hijra perform a traditional song and dance as part of a family's celebration of the birth of a male child; during the performance, they also inspect the newborn's genitals to verify its sex. Herdt states that it is widely accepted that if the child is intersex, the hijra have a right to claim it as part of their community.[11][page needed] However, Warne and Raza argue that an association between intersex and hijra people is mostly unfounded but provokes parental fear.[13] The hijra are mentioned in some versions of the Ramayana, a Hindu epic poem from around 300 BCE,[14] in a myth about the hero Rama instructing his devotees to return to the city Ayodhya rather than follow him across the city's adjacent river into banishment. Since he gives this instruction specifically to "all you men and women," his hijra followers, being neither, remain on the banks of the river for fourteen years until Rama returns from exile.[15]

In the Tantric sect of Hinduism, there is a belief that all individuals possess both male and female components. This belief can be seen explicitly in the Tantric concept of a Supreme Being with both male and female sex organs, which constitutes "one complete sex" and the ideal physical form.[11][page needed]

Ancient Greece

According to Leah DeVun, a "traditional Hippocratic/Galenic model of sexual difference – popularized by the late antique physician Galen and the ascendant theory for much of the Middle Ages – viewed sex as a spectrum that encompassed masculine men, feminine women, and many shades in between, including hermaphrodites, a perfect balance of male and female".[16] DeVun contrasts this with an Aristotelian view of intersex, which argued that "hermaphrodites were not an intermediate sex but a case of doubled or superfluous genitals", and this later influenced Aquinas.[16]

In the mythological tradition, Hermaphroditus was a beautiful youth who was the child of Hermes (Roman Mercury) and Aphrodite (Venus).[17] Ovid wrote the most influential narrative[18] of how Hermaphroditus became androgynous, emphasizing that although the handsome youth was on the cusp of sexual adulthood, he rejected love as Narcissus had, and likewise at the site of a reflective pool.[19] There the water nymph Salmacis saw and desired him. He spurned her, and she pretended to withdraw until, thinking himself alone, he undressed to bathe in her waters. She then flung herself upon him, and prayed that they might never be parted. The gods granted this request, and thereafter the body of Hermaphroditus contained both male and female. As a result, men who drank from the waters of the spring Salmacis supposedly "grew soft with the vice of impudicitia".[20] The myth of Hylas, the young companion of Hercules who was abducted by water nymphs, shares with Hermaphroditus and Narcissus the theme of the dangers that face the beautiful adolescent male as he transitions to adult masculinity, with varying outcomes for each.[21]

Ancient Rome

Pliny notes that "there are even those who are born of both sexes, whom we call hermaphrodites, at one time androgyni" (andr-, "man," and gyn-, "woman", from the Greek).[22] However, the era also saw a historical account of a congenital eunuch.[23]

The Sicilian historian Diodorus (latter 1st-century BC) wrote of "hermaphroditus" in the first century BCE:

Hermaphroditus, as he has been called, who was born of Hermes and Aphrodite and received a name which is a combination of those of both his parents. Some say that this Hermaphroditus is a god and appears at certain times among men, and that he is born with a physical body which is a combination of that of a man and that of a woman, in that he has a body which is beautiful and delicate like that of a woman, but has the masculine quality and vigour of man. But there are some who declare that such creatures of two sexes are monstrosities, and coming rarely into the world as they do they have the quality of presaging the future, sometimes for evil and sometimes for good.[24]

Diodorus also recalled the lives of Diophantus of Abae and Callon of Epidaurus, both of whom had conditions which would correspond with intersex conditions.[25]

Isidore of Seville (c. 560–636) described a hermaphrodite fancifully as those who "have the right breast of a man and the left of a woman, and after coitus in turn can both sire and bear children."[26] Under Roman law, as many others, a hermaphrodite had to be classed as either male or female.[27] Will Roscoe writes that the hermaphrodite represented a "violation of social boundaries, especially those as fundamental to daily life as male and female."[28]

In traditional Roman religion, a hermaphroditic birth was a kind of prodigium, an occurrence that signalled a disturbance of the pax deorum, Rome's treaty with the gods.[29] But Pliny observed that while hermaphrodites were once considered portents, in his day they had become objects of delight (deliciae) who were trafficked in an exclusive slave market.[30] According to historian John R. Clarke, depictions of Hermaphroditus were very popular among the Romans:

Artistic representations of Hermaphroditus bring to the fore the ambiguities in sexual differences between women and men as well as the ambiguities in all sexual acts. ... (A)rtists always treat Hermaphroditus in terms of the viewer finding out his/her actual sexual identity. ... Hermaphroditus is a highly sophisticated representation, invading the boundaries between the sexes that seem so clear in classical thought and representation.[31]

In c.400, Augustine wrote in The Literal Meaning of Genesis that humans were created in two sexes, despite "as happens in some births, in the case of what we call androgynes".[16]

Historical accounts of intersex people include the sophist and philosopher Favorinus, described as a eunuch (εὐνοῦχος) by birth.[23][32] Mason and others thus describe Favorinus as having an intersex trait.[3][33][34]

A broad sense of the term "eunuch" is reflected in the compendium of ancient Roman laws collected by Justinian I in the 6th century known as the Digest or Pandects. Those texts distinguish between the general category of eunuchs (spadones, denoting "one who has no generative power, an impotent person, whether by nature or by castration",[35] D 50.16.128) and the more specific subset of castrati (castrated males, physically incapable of procreation). Eunuchs (spadones) sold in the slave markets were deemed by the jurist Ulpian to be "not defective or diseased, but healthy", because they were anatomically able to procreate just like monorchids (D 21.1.6.2). On the other hand, as Julius Paulus pointed out, "if someone is a eunuch in such a way that he is missing a necessary part of his body" (D 21.1.7), then he would be deemed diseased. In these Roman legal texts, spadones (eunuchs) are eligible to marry women (D 23.3.39.1), institute posthumous heirs (D 28.2.6), and adopt children (Institutions of Justinian 1.11.9), unless they are castrati.

Middle Ages

Islam

By the eighth century CE, records of Islamic legal rulings discuss individuals known in Arabic as khuntha. This term, which has been translated as "hermaphrodite," was used to apply to individuals with a range of intersex conditions, including mixed gonadal disgenesis, male hypospadias, partial androgen insensitivity syndrome, 5-alpha reductase deficiency, gonadal aplasia, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia.[36]

In Islamic law, inheritance was determined based on sex, so it was sometimes necessary to attempt to determine the biological sex of sexually ambiguous heirs.[36] The first recorded case of this sort has been attributed to the seventh-century Rashidun caliph named 'Ali, who attempted to settle an inheritance case between five brothers in which one brother had both a male and female urinary opening. 'Ali advised the brothers that sex could be determined by site of urination in a practice called hukm al-mabal; if urine exited the male opening, the individual was male, and if it exited the female opening, the individual was female. If it exited both openings simultaneously, as it did in this case, the heir would be given half of a male inheritance and half of a female inheritance.[36][37] Later, in the thirteenth century CE, Shafi'i law expert Abu Zakariya al-Nawawi ruled that an individual whose sex could not be determined by hukm al-mabal, such as those with urination from both openings or those with no identifiable sex organs, was assigned the intermediary sex category khuntha mushkil.[36][37]

Both Hanafi and Hanbali lawmakers also recognized that puberty could clarify a new dominant sex in intersex individuals who were labeled khuntha, male, or female in childhood. If a khuntha or male developed female secondary sex characteristics, performed vaginal sex, lactated, menstruated, or conceived, this person's legal sex could change to female. Conversely, if a khuntha or female developed male secondary sex characteristics, performed penetrative sex with a woman, or had an erection, their legal sex could change to male. This understanding of the effect of puberty on intersex conditions appears in Islamic law as early as the eleventh century CE, notably by Ibn Qudama.[36]

In the sixteenth century CE, Ibrahim al-Halabi, a member of the Hanafi school of jurisprudence in Islam, directed slave owners to use special gender-neutral language when freeing intersex slaves. He recognized that language manumitting "males" or "females" would not directly apply to them.[36]

Christianity

In Abnormal (Les anormaux), Michel Foucault suggested it is likely that, "from the Middle Ages to the sixteenth century ... hermaphrodites were considered to be monsters and were executed, burnt at the stake and their ashes thrown to the winds."[38]

However, Christof Rolker disputes this, arguing that "Contrary to what has been claimed, there is no evidence for hermaphrodites being persecuted in the Middle Ages, and the learned laws did certainly not provide any basis for such persecution".[39] Canon Law sources provide evidence of alternative perspectives, based upon prevailing visual indications and the performance of gendered roles.[40] The 12th-century Decretum Gratiani states that "Whether an hermaphrodite may witness a testament, depends on which sex prevails" ("Hermafroditus an ad testamentum adhiberi possit, qualitas sexus incalescentis ostendit.").[41][42]

In the late twelfth century, the canon lawyer Huguccio stated that, "If someone has a beard, and always wishes to act like a man (excercere virilia) and not like a female, and always wishes to keep company with men and not with women, it is a sign that the male sex prevails in him and then he is able to be a witness, where a woman is not allowed".[43] Concerning the ordination of 'hermaphrodites', Huguccio concluded: "If therefore the person is drawn to the feminine more than the male, the person does not receive the order. If the reverse, the person is able to receive but ought not to be ordained on account of deformity and monstrosity."[43]

Henry de Bracton's De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae ("On the Laws and Customs of England"), c. 1235,[44] classifies mankind as "male, female, or hermaphrodite",[45] and "A hermaphrodite is classed with male or female according to the predominance of the sexual organs."[46]

The thirteenth-century canon lawyer Henry of Segusio argued that a "perfect hermaphrodite" where no sex prevailed should choose their legal gender under oath.[47][39]

Archaeology

A 2021 study in the European Journal of Archaeology concluded that a grave from 1050 to 1300 in Hattula, Finland, containing a body buried in feminine clothing with brooches, furs and a hiltless sword, which earlier researchers speculated to be two bodies (a male and female) or a powerful woman, was one person with Klinefelter syndrome and that "the overall context of the grave indicates that it was a respected person".[48][49]

Early modern period

The 17th-century English jurist and judge Edward Coke (Lord Coke), wrote in his Institutes of the Lawes of England on laws of succession stating, "Every heire is either a male, a female, or an hermaphrodite, that is both male and female. And an hermaphrodite (which is also called Androgynus) shall be heire, either as male or female, according to that kind of sexe which doth prevaile."[50][51] The Institutes are widely held to be a foundation of common law.

A few historical accounts of intersex people exist due primarily to the discovery of relevant legal records, including those of Thomas(ine) Hall (17th-century United States), Eleno de Céspedes, a 16th-century intersex person in Spain (in Spanish), and Fernanda Fernández (18th-century Spain).

In 2019 the Smithsonian Channel aired a documentary "American's Hidden Stories: The General was Female?" with evidence that Casimir Pulaski, the important American Revolutionary War hero, may have been intersex.[52]

In a court case, heard at the Castellania in 1774 during the Order of St. John in Malta, 17-year-old Rosa Mifsud from Luqa, later described in the British Medical Journal as a pseudo-hermaphrodite, petitioned for a change in sex classification from female.[53][54] Two clinicians were appointed by the court to perform an examination. They found that "the male sex is the dominant one".[54] The examiners were the Physician-in-Chief and a senior surgeon, both working at the Sacra Infermeria.[54] The Grandmaster himself made the final decision that Mifsud would, from that point forward, wear only male garb.[53]

Maria Dorothea Derrier/Karl Dürrge was a German intersex person who made their living for 30 years as a human research subject. Born in Potsdam in 1780, and designated as female at birth, they assumed a male identity around 1807. Traveling intersex persons, like Derrier and Katharina/Karl Hohmann, who allowed themselves to be examined by physicians were instrumental in the development of codified standards for sexing.[55][56]

Mid-modern period

During the Victorian era, medical authors attempted to ascertain whether or not humans could be hermaphrodites, adopting a precise biological definition to the term.[57] During this period, doctors introduced the terms "true hermaphrodite" for an individual who has both ovarian and testicular tissue, verified under a microscope, "male pseudo-hermaphrodite" for a person with testicular tissue, but either female or ambiguous sexual anatomy, and "female pseudo-hermaphrodite" for a person with ovarian tissue, but either male or ambiguous sexual anatomy.

Historical accounts including those of Vietnamese general Lê Văn Duyệt (18th/19th-century) who helped to unify Vietnam; Gottlieb Göttlich, a 19th-century German travelling medical case; and Levi Suydam, an intersex person in 19th-century USA whose capacity to vote in male-only elections was questioned.

The memoirs of 19th-century intersex Frenchwoman Herculine Barbin were published by Michel Foucault in 1980.[58] Her birthday is marked in Intersex Day of Remembrance on 8 November.

Contemporary period

The term intersexuality was coined by Richard Goldschmidt in the 1917 paper Intersexuality and the endocrine aspect of sex.[59][60][61] The first suggestion to replace the term 'hermaphrodite' with 'intersex' came from British specialist Cawadias in the 1940s.[62] This suggestion was taken up by specialists in the UK during the 1960s.[63][64] Historical accounts from the early twentieth century include that of Australian Florrie Cox, whose marriage was annulled due to "malformation frigidity".[5]

Since the rise of modern medical science in Western societies, some intersex people with ambiguous external genitalia have had their genitalia surgically modified to resemble either female or male genitals. Surgeons pinpointed intersex babies as a "social emergency" once they were born.[65] The parents of the intersex babies were not content about the situation. Psychologists, sexologists, and researchers frequently still believe that it is better for a baby's genitalia to be changed when they are younger than when they are a mature adult. These scientists believe that early intervention helped avoid gender identity confusion.[66] This was called the 'Optimal Gender Policy', and it was initially developed in the 1950s by John Money.[67] Money and others believed that children would in general develop a gender identity that matched sex of rearing (this view has since been challenged, based in part on Money's inaccurate reporting of success in the infant sex reassignment of David Reimer).[68] The primary goal of assignment was to choose the sex that would lead to the least inconsistency between external anatomy and assigned psyche (gender identity).

Since advances in surgery have made it possible for intersex conditions to be concealed, many people are not aware of how frequently intersex conditions arise in human beings or that they occur at all.[69] Dialog between what were once antagonistic groups of activists and clinicians has led to only slight changes in medical policies and how intersex patients and their families are treated in some locations.[70] Numerous civil society organizations and human rights institutions now call for an end to unnecessary "normalizing" interventions.

The first public demonstration by intersex people took place in Boston on October 26, 1996, outside the venue in Boston where the American Academy of Pediatrics was holding its annual conference.[71] The group demonstrated against "normalizing" treatments, and carried a sign saying "Hermaphrodites With Attitude".[72] The event is now commemorated by Intersex Awareness Day.[73]

In 2011, Christiane Völling became the first intersex person known to have successfully sued for damages in a case brought for non-consensual surgical intervention.[74] In April 2015, Malta became the first country to outlaw non-consensual medical interventions to modify sex anatomy, including that of intersex people.[75][76]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ "Free & Equal Campaign Fact Sheet: Intersex" (PDF). United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Domurat Dreger, Alice (2001). Hermaphrodites and the Medical Invention of Sex. USA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00189-3.

- ^ a b Mason, H.J., Favorinus’ Disorder: Reifenstein's Syndrome in Antiquity?, in Janus 66 (1978) 1–13.

- ^ Nguyễn Khắc Thuần (1998), Việt sử giai thoại (History of Vietnam's tales), vol. 8, Vietnam Education Publishing House, p. 55

- ^ a b Richardson, Ian D. (May 2012). God's Triangle. Preddon Lee Limited. ISBN 9780957140103.

- ^ Dreger, Alice D; Chase, Cheryl; Sousa, Aron; Gruppuso, Phillip A.; Frader, Joel (18 August 2005). "Changing the Nomenclature/Taxonomy for Intersex: A Scientific and Clinical Rationale" (PDF). Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. 18 (8): 729–33. doi:10.1515/JPEM.2005.18.8.729. PMID 16200837. S2CID 39459050. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ a b "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". Archived from the original on 24 December 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ Winter, Gopi Shankar (2014). Maraikkappatta Pakkangal: மறைக்கப்பட்ட பக்கங்கள். Srishti Madurai. ISBN 9781500380939. OCLC 703235508.

- ^ Swami., Parmeshwaranand (2004). Encyclopaedia of the Śaivism (1st ed.). New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. ISBN 978-8176254274. OCLC 54930404.

- ^ Shankar, Gopi (March–April 2015). "The Many Genders of Old India". The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide. 22: 24–26 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c d e Herdt, Gilbert, ed. (1996). "Hijras: An Alternative Sex and Gender Role in India". Third Sex, Third Gender: Beyond Sexual Dimorphism in Culture and History. New York: Zone Books.

- ^ Nanda, Serena. Neither Man Nor Woman: The hijras of India, p. xx. Canada: Wadworth Publishing Company, 1999

- ^ Warne, Garry L.; Raza, Jamal (September 2008). "Disorders of sex development (DSDs), their presentation and management in different cultures". Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 9 (3): 227–236. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.469.9016. doi:10.1007/s11154-008-9084-2. ISSN 1389-9155. PMID 18633712. S2CID 8897416.

- ^ "Ramayana | Indian epic". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- ^ Reddy, Gayatri (Spring 2003). ""Men" Who Would Be Kings: Celibacy, Emasculation, and the Re-Production of Hijras in Contemporary Indian Politics". Social Research. 70: 163–200. doi:10.1353/sor.2003.0050. S2CID 142842776.

- ^ a b c DeVun, Leah (June 2018). "Heavenly hermaphrodites: sexual difference at the beginning and end of time". Postmedieval. 9 (2): 132–146. doi:10.1057/s41280-018-0080-8. ISSN 2040-5960. S2CID 165449144.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 4.287–88.

- ^ Taylor, The Moral Mirror of Roman Art, p. 77; Clarke, Looking at Lovemaking, p. 49.

- ^ Taylor, The Moral Mirror of Roman Art, p. 78ff.

- ^ Paulus ex Festo 439L; Richlin, "Not before Homosexuality," p. 549.

- ^ Taylor, The Moral Mirror of Roman Art, p. 216, note 46.

- ^ Pliny, Natural History 7.34: gignuntur et utriusque sexus quos hermaphroditos vocamus, olim androgynos vocatos; Veronique Dasen, "Multiple Births in Graeco-Roman Antiquity," Oxford Journal of Archaeology 16.1 (1997), p. 61.

- ^ a b Philostratus, VS 489

- ^ Diodorus Siculus (1935). Library of History (Book IV). Loeb Classical Library Volumes 303 and 340. C H Oldfather (trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Archived from the original on 2008-09-27.

- ^ Markantes, Georgios; Deligeoroglou, Efthimios; Armeni, Anastasia; Vasileiou, Vasiliki; Damoulari, Christina; Mandrapilia, Angelina; Kosmopoulou, Fotini; Keramisanou, Varvara; Georgakopoulou, Danai; Creatsas, George; Georgopoulos, Neoklis (2015-07-10). "Callo: The first known case of ambiguous genitalia to be surgically repaired in the history of Medicine, described by Diodorus Siculus". Hormones. 14 (3): 459–461. doi:10.14310/horm.2002.1608. PMID 26188239.

- ^ Isidore of Seville, Eytmologiae 11.3. 11.

- ^ Lynn E. Roller, "The Ideology of the Eunuch Priest," Gender & History 9.3 (1997), p. 558.

- ^ Will Roscoe, "Priests of the Goddess: Gender Transgression in Ancient Religion," History of Religions 35, no. 3 (Feb., 1996): 195-230.

- ^ Veit Rosenberger, "Republican nobiles: Controlling the Res Publica," in A Companion to Roman Religion (Blackwell, 2007), p. 295.

- ^ Plutarch, Moralia 520c; Dasen, "Multiple Births in Graeco-Roman Antiquity," p. 61.

- ^ Clarke, Looking at Lovemaking, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Swain, Simon (1989). "Favorinus and Hadrian". ZPE. 79: 150–158.

- ^ Horstmanshoff (2000) 103 n. 39

- ^ Eugenio Amato (intr., ed., comm.) and Yvette Julien (trans.), Favorinos d'Arles, Oeuvres I. Introduction générale - Témoignages - Discours aux Corinthiens - Sur la Fortune, Paris: Les Belles Lettres (2005).

- ^ "Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary". Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f Gesink, Indira Falk (July 2018). "Intersex Bodies in Premodern Islamic Discourse". Journal of Middle East Women's Studies. 14 (2): 152–173. doi:10.1215/15525864-6680205. S2CID 149824248.

- ^ a b Haneef, Sayed Sikandar Shah; Abd Majid, Mahmood Zuhdi Haji (December 2015). "Medical Management of Infant Intersex: The Juridico-Ethical Dilemma of Contemporary Islamic Legal Response". Zygon: Journal of Religion & Science. 50 (4): 809–829. doi:10.1111/zygo.12220.

- ^ Foucault, Michel (2003). Abnormal: Lectures at the Collège de France 1974-1975. Verso. p. 67.

- ^ a b Rolker, Christof (2014-01-01). "The two laws and the three sexes: ambiguous bodies in canon law and Roman law (12th to 16th centuries)". Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte: Kanonistische Abteilung. 100 (1): 178–222. doi:10.7767/zrgka-2014-0108. ISSN 2304-4896. S2CID 159668229.

- ^ Rolker, Christof (2013). "Double sex, double pleasure? Hermaphrodites and the medieval laws". For a German Version, See Christof Rolker, der Hermaphrodit und Seine Frau. Körper, Sexualität und Geschlecht Im Spätmittelalter, in: Historische Zeitschrift 297 (2013), 593–620. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2016-08-27.

- ^ Decretum Gratiani, C. 4, q. 2 et 3, c. 3

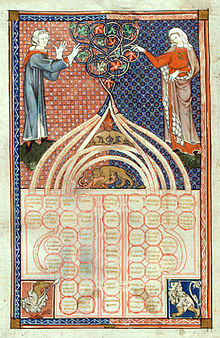

- ^ "Decretum Gratiani (Kirchenrechtssammlung)". Bayerische StaatsBibliothek (Bavarian State Library). February 5, 2009. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Raming, Ida; Macy, Gary; Bernard J, Cook (2004). A History of Women and Ordination. Scarecrow Press. p. 113.

- ^ Henry de Bracton. (2009). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 17 March 2009, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online Archived 2009-03-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ de Bracton, Henry. On the Laws and Customs of England. Vol. 2 (Thorne ed.). p. 31. Archived from the original on 2016-10-29. Retrieved 2016-10-02.

- ^ de Bracton, Henry. On the Laws and Customs of England. Vol. 2 (Thorne ed.). p. 32. Archived from the original on 2016-10-29. Retrieved 2016-10-02.

- ^ Henrici de Segusio, Cardinalis Hostiensis, Summa aurea, Venice 1574 here at col. 612.

- ^ Jon Henley, 1,000-year-old remains in Finland may be non-binary iron age leader, 9 August 2021, The Guardian: "If the characteristics of Klinefelter syndrome were evident, Moilanen said, the person 'might not have been considered strictly a female or a male in the early middle ages community. The abundant collection of objects buried in the grave is proof that the person was not only accepted, but also valued and respected.'"

- ^ Ulla Moilanen, Tuija Kirkinen, Nelli-Johanna Saari, Adam B. Rohrlach, Johannes Krause, Päivi Onkamo, Elina Salmela, "A Woman with a Sword? – Weapon Grave at Suontaka Vesitorninmäki, Finland", in the European Journal of Archaeology, 1-19 (15 July 2021), doi:10.1017/eaa.2021.30

- ^ E Coke, The First Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England, Institutes 8.a. (1st Am. Ed. 1812).

- ^ Greenberg, Julie (1999). "Defining Male and Female: Intersexuality and the Collision Between Law and Biology". Arizona Law Review. 41: 277–278. SSRN 896307.

- ^ Katz, Brigit (April 9, 2019). "Was the Revolutionary War Hero Casimir Pulaski Intersex?". Smithsonianmag.com. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Savona-Ventura, Charles (2015). Knight Hospitaller Medicine in Malta [1530–1798]. Lulu. p. 115. ISBN 978-1326482220. Archived from the original on 2017-02-06.

- ^ a b c Cassar, Paul (11 December 1954). "Change of Sex Sanctioned by a Maltese Law Court in the Eighteenth Century". British Medical Journal. 2 (4901): 1413. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4901.1413. PMC 2080334. PMID 13209141. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2017.

- ^ Johnson, Matthew (2005). "This is Not a Hermaphrodite: The Medical Assimilation of Gender Difference in Germany around 1800". Canadian Bulletin of Medical History. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. 22 (2): 233–252. doi:10.3138/cbmh.22.2.233. ISSN 0823-2105. PMID 16482692.

- ^ Sera, Stephanie (April 2019). "Ein unvollendetes Porträt. Der Hermaphrodit Maria Derrier/Karl Dürrge in medizinischen Fallberichten des frühen 19. Jahrhunderts" [An Unfinished Portrait: The Hermaphrodite Maria Derrier / Karl Dürrge in Medical Case Reports of the Early 19th Century]. L'Homme (in German). France: École des hautes études en sciences sociales. 30 (1): 51–68. doi:10.14220/lhom.2019.30.1.51. ISSN 2194-5071. S2CID 166501980.

- ^ Reis, Elizabeth (2009). Bodies in Doubt: an American History of Intersex. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 55–81. ISBN 978-0-8018-9155-7.

- ^ Barbin, Herculine (1980). Herculine Barbin: Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth-century French Hermaphrodite. introd. Michel Foucault, trans. Richard McDougall. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-394-50821-4.

- ^ Goldschmidt, R. (1917), "Intersexuality and the endocrine aspect of sex", Endocrinology, 1 (4): 433–456, doi:10.1210/endo-1-4-433.

- ^ Hirschfeld, M. (1923) 'Die Intersexuelle Konstitution.' Jahrbuch fuer sexuelle Zwischenstufen, 23, 3–27.

- ^ Voss, Heinz-Juergen. "Sex In The Making - A Biological Account" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-01. Retrieved 2018-01-04.

- ^ Cawadias, A. P. (1943) Hermaphoditus the Human Intersex, London, Heinemann Medical Books Ltd.

- ^ Armstrong, C. N. (1964) "Intersexuality in Man", IN ARMSTRONG, C. N. & MARSHALL, A. J. (Eds.) Intersexuality in Vertebrates Including Man, London, New York, Academic Press Ltd.

- ^ Dewhurst, S. J. & Gordon, R. R. (1969) The Intersexual Disorders, London, Baillière Tindall & Cassell.

- ^ Coran, Arnold G.; Polley, Theodore Z. (July 1991). "Surgical management of ambiguous genitalia in the infant and child". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 26 (7): 812–820. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.628.4867. doi:10.1016/0022-3468(91)90146-K. PMID 1895191.

- ^ Fausto-Sterling, Anne (2000). Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-07713-7.

- ^ National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics (November 2012). On the management of differences of sex development. Ethical issues relating to "intersexuality".Opinion No. 20/2012 (PDF). Berne, Switzerland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-23. Retrieved 2016-08-27.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Australian Senate; Community Affairs References Committee (October 2013). Involuntary or coerced sterilisation of intersex people in Australia. Canberra: Community Affairs References Committee. ISBN 9781742299174. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23.

- ^ Dreger, Alice Domurat (May 1998). ""Ambiguous Sex"--or Ambivalent Medicine?"". Hastings Center Report. 28 (3): 24–35. doi:10.2307/3528648. JSTOR 3528648. PMID 9669179.

- ^ Dreger, Alice (3 April 2015). "Malta Bans Surgery on Intersex Children". The Stranger SLOG. Archived from the original on 18 July 2015.

- ^ Holmes, Morgan (17 October 2015). "When Max Beck and Morgan Holmes went to Boston". Intersex Day. Archived from the original on 20 October 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

- ^ Beck, Max. "Hermaphrodites with Attitude Take to the Streets". Intersex Society of North America. Archived from the original on 2015-10-05. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

- ^ Driver, Betsy (14 October 2015). "The origins of Intersex Awareness Day". Intersex Day. Archived from the original on 20 October 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

- ^ International Commission of Jurists. "In re Völling, Regional Court Cologne, Germany (6 February 2008)". Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ "Surgery and Sterilization Scrapped in Malta's Benchmark LGBTI Law". The New York Times. Reuters. 1 April 2015.

- ^ "Malta passes law outlawing forced surgical intervention on intersex minors". Star Observer. 2 April 2015. Archived from the original on 14 August 2015.