John Winthrop

John Winthrop | |

|---|---|

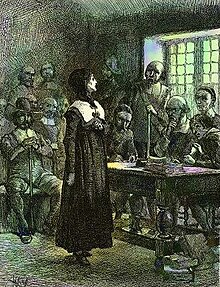

A 17th century portrait of Winthrop | |

| 2nd, 6th, 9th, and 12th Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony | |

| In office 1630–1634 | |

| Preceded by | John Endecott |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Dudley |

| In office 1637–1640 | |

| Preceded by | Henry Vane |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Dudley |

| In office 1642–1644 | |

| Preceded by | Richard Bellingham |

| Succeeded by | John Endecott |

| In office 1646–1649 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Dudley |

| Succeeded by | John Endecott |

| Commissioner for Massachusetts Bay[1] | |

| In office 1643–1643 Serving with Thomas Dudley | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | |

| In office 1645–1645 Serving with Herbert Pelham | |

| Preceded by |

|

| Succeeded by | Herbert Pelham |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 12 January 1587/1588 Edwardstone, Suffolk, England |

| Died | March 26, 1649 (aged 62) Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 16 |

| Education | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Profession | Lawyer, governor |

| Signature |  |

John Winthrop (January 12, 1588[a] – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and a leading figure in the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led the first large wave of colonists from England in 1630 and served as governor for 12 of the colony's first 20 years. His writings and vision of the colony as a Puritan "city upon a hill" dominated New England colonial development, influencing the governments and religions of neighboring colonies in addition to those of Massachusetts.

Winthrop was born into a wealthy land-owning and merchant family. He trained in the law and became Lord of the Manor at Groton in Suffolk, England. He was not involved in founding the Massachusetts Bay Company in 1628, but he became involved in 1629 when anti-Puritan King Charles I began a crackdown on Nonconformist religious thought. In October 1629, he was elected governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and he led a group of colonists to the New World in April 1630, founding a number of communities on the shores of Massachusetts Bay and the Charles River.

Between 1629 and his death in 1649, he served 18 annual terms as governor or lieutenant-governor and was a force of comparative moderation in the religiously conservative colony, clashing with the more conservative Thomas Dudley and the more liberal Roger Williams and Henry Vane. Winthrop was a respected political figure, and his attitude toward governance seems authoritarian to modern sensibilities. He resisted attempts to widen voting and other civil rights beyond a narrow class of religiously approved individuals, opposed attempts to codify a body of laws that the colonial magistrates would be bound by, and also opposed unconstrained democracy, calling it "the meanest and worst of all forms of government".[2] The authoritarian and religiously conservative nature of Massachusetts rule was influential in the formation of neighboring colonies, which were formed in some instances by individuals and groups opposed to the rule of the Massachusetts elders.

Winthrop's son John was one of the founders of the Connecticut Colony, and Winthrop himself wrote one of the leading historical accounts of the early colonial period. His long list of descendants includes famous Americans, and his writings continue to influence politicians today.

Life in England

John Winthrop was born on January 12, 1587/8[a][3] to Adam and Anne (née Browne) Winthrop in Edwardstone, Suffolk, England. His birth was recorded in the parish register at Groton.[4] His father's family had been successful in the textile business, and his father was a lawyer and prosperous landowner with several properties in Suffolk.[5] His mother's family was also well-to-do, with properties in Suffolk and Essex.[6] When Winthrop was young, his father became a director at Trinity College, Cambridge.[7] Winthrop's uncle John (Adam's brother) immigrated to Ireland, and the Winthrop family took up residence at Groton Manor.[8]

Winthrop was first tutored at home by John Chaplin and was assumed to have attended grammar school at Bury St. Edmunds.[9] He was also regularly exposed to religious discussions between his father and clergymen, and thus came to a deep understanding of theology at an early age. He was admitted to Trinity College in December 1602,[10] matriculating at the university a few months later.[11] Among the students with whom he would have interacted were John Cotton and John Wheelwright, two men who also had important roles in New England.[12] He was a close childhood and university friend of William Spring, later a Puritan Member of Parliament with whom he corresponded for the rest of his life.[13] The teenage Winthrop admitted in his diary of the time to "lusts ... so masterly as no good could fasten upon me."[14] Biographer Francis Bremer suggests that Winthrop's need to control his baser impulses may have prompted him to leave school early and marry at an unusually early age.[15]

In 1604, Winthrop journeyed to Great Stambridge in Essex with a friend.[16] They stayed at the home of a family friend, and Winthrop was favorably impressed with their daughter Mary Forth.[17] He left Trinity College to marry her on April 16, 1605, at Great Stambridge.[18] Mary bore him five children, of whom only three survived to adulthood.[19] The oldest of their children was John Winthrop the Younger, who became a governor and magistrate of Connecticut Colony.[20][21] Their last two children, both girls, died not long after birth, and Mary died in 1615 from complications of the last birth.[19] The couple spent most of their time at Great Stambridge, living on the Forth estate.[22] In 1613, Adam Winthrop transferred the family holdings in Groton to Winthrop, who then became Lord of the Manor at Groton.[23]

Lord of the Manor

As lord of the manor, Winthrop was deeply involved in the management of the estate, overseeing the agricultural activities and the manor house.[24] He eventually followed his father in practicing law in London, which would have brought him into contact with the city's business elite.[25] He was also appointed to the county commission of the peace, a position that gave him a wider exposure among other lawyers and landowners and a platform to advance what he saw as God's kingdom.[26] The commission's responsibilities included overseeing countywide issues, including road and bridge maintenance and the issuance of licenses. Some of its members were also empowered to act as local judges for minor offenses, although Winthrop was only able to exercise this authority in cases affecting his estate.[27] The full commission met quarterly, and Winthrop forged a number of important connections through its activities.[28]

Winthrop documented his religious life, keeping a journal beginning 1605 in which he described his religious experiences and feelings.[22][29] In it, he described his failures to keep "divers vows" and sought to reform his failings by God's grace, praying that God would "give me a new heart, joy in his spirit; that he would dwell with me".[30] He was somewhat distressed that his wife did not share the intensity of his religious feelings, but he eventually observed that "she proved after a right godly woman."[31] He was more intensely religious than his father, whose diaries dealt almost exclusively with secular matters.[32]

His wife Mary died in 1615, and he followed the custom of the time by marrying Thomasine Clopton soon after on December 6, 1615. She was more pious than Mary had been; Winthrop wrote that she was "truly religious & industrious therein".[33] Thomasine died on December 8, 1616, from complications of childbirth; the child did not survive.[33]

In approximately 1613 (records indicate that it may have been earlier), Winthrop was enrolled at Gray's Inn. There he read the law but did not advance to the Bar.[34] His legal connections introduced him to the Tyndal family of Great Maplestead, Essex, and he began courting Margaret Tyndal in 1617, the daughter of chancery judge Sir John Tyndal and his wife Anne Egerton, sister of Puritan preacher Stephen Egerton. Her family was initially opposed to the match on financial grounds;[35] Winthrop countered by appealing to piety as a virtue which more than compensated for his modest income. The couple were married on April 29, 1618, at Great Maplestead.[36] They continued to live at Groton, although Winthrop necessarily divided his time between Groton and London, where he eventually acquired a highly desirable post in the Court of Wards and Liveries. His eldest son John sometimes assisted Margaret with the management of the estate while he was away.[37]

Decision to begin voyage and settlement in the American colonies

In the mid- to late-1620s, the religious atmosphere in England began to look bleak for Puritans and other groups whose adherents believed that the English Reformation was in danger. King Charles I had ascended the throne in 1625, and he had married a Roman Catholic. Charles was opposed to all manner of recusants and supported the Church of England in its efforts against religious groups such as the Puritans that did not adhere fully to its teachings and practices.[38] This atmosphere of intolerance led Puritan religious and business leaders to consider emigration to the New World as a viable means to escape persecution.[39]

The first successful religious colonization of the New World occurred in 1620 with the establishment of the Plymouth Colony on the shores of Cape Cod Bay.[40] Pastor John White led a short-lived effort to establish a colony at Cape Ann in 1624, also on the Massachusetts coast.[41] In 1628, some of the investors in that effort joined with new investors to acquire a land grant for the territory roughly between the Charles and Merrimack Rivers. It was first styled the New England Company, then renamed the Massachusetts Bay Company in 1629 after it acquired a royal charter granting it permission to govern the territory.[42] Shortly after acquiring the land grant in 1628, it sent a small group of settlers led by John Endecott to prepare the way for further migration.[43] John Winthrop was apparently not involved in any of these early activities, which primarily involved individuals from Lincolnshire; however, he was probably aware of the company's activities and plans by early 1629. The exact connection is uncertain by which he became involved with the company because there were many indirect connections between him and individuals associated with the company.[44] Winthrop was also aware of attempts to colonize other places; his son Henry became involved in efforts to settle Barbados in 1626, which Winthrop financially supported for a time.[45]

In March 1629, King Charles dissolved Parliament, beginning eleven years of rule without Parliament.[38] This action apparently raised new concerns among the company's principals; in their July meeting, Governor Matthew Cradock proposed that the company reorganize itself and transport its charter and governance to the colony.[46] It also worried Winthrop, who lost his position in the Court of Wards and Liveries in the crackdown on Puritans that followed the dissolution of Parliament. He wrote, "If the Lord seeth it wilbe good for us, he will provide a shelter & a hidinge place for us and others".[38] During the following months, he became more involved with the company, meeting with others in Lincolnshire. By early August, he had emerged as a significant proponent of emigration, and he circulated a paper on August 12 providing eight separate reasons in favor of emigration.[47] His name appears in formal connection with the company on the Cambridge Agreement signed August 26; this document provided means for emigrating shareholders to buy out non-emigrating shareholders of the company.[48]

The company shareholders met on October 20 to enact the changes agreed to in August. Governor Cradock was not emigrating and a new governor needed to be chosen. Winthrop was seen as the most dedicated of the three candidates proposed to replace Cradock, and he won the election. The other two were Richard Saltonstall and John Humphrey; they had many other interests, and their dedication to settling in Massachusetts was viewed as uncertain.[49] Humphrey was chosen as deputy governor, a post that he relinquished the following year when he decided to delay his emigration.[50] Winthrop and other company officials then began the process of arranging a transport fleet and supplies for the migration. He also worked to recruit individuals with special skills that the new colony would require, including pastors to see to the colony's spiritual needs.[51]

It was unclear to Winthrop when his wife would come over; she was due to give birth in April 1630, near the fleet's departure time. They consequently decided that she would not come over until a later time, and it was not until 1631 that the couple were reunited in the New World.[52] To maintain some connection with his wife during their separation, the couple agreed to think of each other between the hours of 5 and 6 in the evening each Monday and Friday.[53] Winthrop also worked to convince his grown children to join the migration; John Jr. and Henry both decided to do so, but only Henry sailed in the 1630 fleet.[54] By April 1630, Winthrop had put most of his affairs in order, although Groton Manor had not yet been sold because of a long-running title dispute. The legal dispute was only resolved after his departure, and the property's sale was finalized by Margaret before she and John Jr. left for the colony.[55]

Coat of arms

John Winthrop used a coat of arms that was reportedly confirmed to his paternal uncle by the College of Arms, London in 1592. It was also used by his sons. These arms appear on his tombstone in the King's Chapel Burying Ground. It is also the coat of arms for Winthrop House at Harvard University and is displayed on the 1675 house of his youngest son Deane Winthrop at the Deane Winthrop House. The heraldic blazon of arms is Argent three chevronels Gules overall a lion rampant Sable.[56]

Massachusetts Bay Colony

Arrival

On April 8, 1630, four ships left the Isle of Wight carrying Winthrop and other leaders of the colony. Winthrop sailed on the Arbella, accompanied by his two young sons Samuel[b] and Stephen.[57] The ships were part of a larger fleet totalling 11 ships that carried about 700 migrants to the colony.[58] Winthrop's son Henry Winthrop missed the Arbella's sailing and ended up on the Talbot, which also sailed from Wight.[20][21] A sermon titled "A Modell of Christian Charitie", delivered either before or during the crossing, has historically been attributed to Winthrop, but the sermon's authorship is disputed; John Wilson or George Phillips, two ministers who sailed with the Arbella, may have authored the sermon.[59]

"A Modell of Christian Charitie" described the ideas and plans to keep the Puritan society strong in faith, while also comparing the struggles that they would have to overcome in the New World with the story of Exodus. The sermon used the now-famous phrase "City upon a Hill" to describe the ideals to which the colonists should strive, and that consequently "the eyes of all people are upon us."[60] The sermon also said, "In all times some must be rich some poore, some highe and eminent in power and dignitie; others meane and in subjection"; that is, all societies include some who are rich and successful and others who are poor and subservient—and both groups were equally important to the colony because both groups were members to the same community.[9]

The fleet arrived at Salem in June and was welcomed by John Endecott. Winthrop and his deputy Thomas Dudley found the Salem area inadequate for a settlement suitable for all of the arriving colonists, and they embarked on surveying expeditions of the area. They first decided to base the colony at Charlestown, but a lack of good water there prompted them to move to the Shawmut Peninsula where they founded what is now the city of Boston.[61] The season was relatively late, and the colonists decided to establish dispersed settlements along the coast and the banks of the Charles River in order to avoid presenting a single point that hostile forces might attack. These settlements became Boston, Cambridge, Roxbury, Dorchester, Watertown, Medford, and Charlestown.

The colony struggled with disease in its early months, losing as many as 200 people to a variety of causes in 1630, including Winthrop's son Henry, and about 80 others who returned to England in the spring due to these conditions.[9][33] Winthrop set an example to the other colonists by working side by side with servants and laborers in the work of the colony. According to one report, he "fell to work with his own hands, and thereby so encouraged the rest that there was not an idle person to be found in the whole plantation."[62]

Winthrop built his house in Boston where he also had a relatively spacious plot of arable land.[63] In 1631, he was granted a larger parcel of land on the banks of the Mystic River that he called Ten Hills Farm.[64] On the other side of the Mystic was the shipyard owned in absentia by Matthew Cradock, where one of the colony's first boats was built, Winthrop's Blessing of the Bay. Winthrop operated her as a trading and packet ship up and down the coast of New England.[65]

The issue of where to locate the colony's capital caused the first in a series of rifts between Winthrop and Dudley. Dudley had constructed his home at Newtown (present-day Harvard Square, Cambridge) after the council had agreed that the capital would be established there. However, Winthrop decided instead to build his home in Boston when asked by its residents to stay there. This upset Dudley, and their relationship worsened when Winthrop criticized Dudley for what he perceived as excessive decorative woodwork in his house.[66] However, they seemed to reconcile after their children were married. Winthrop recounts the two of them, each having been granted land near Concord, going to stake their claims. At the boundary between their lands, a pair of boulders were named the Two Brothers "in remembrance that they were brothers by their children's marriage".[67] Dudley's lands became Bedford, and Winthrop's Billerica.[68]

Colonial governance

The colony's charter called for a governor, deputy governor, and 18 assistant magistrates who served as a precursor to the idea of a Governor's Council. All these officers were to be elected annually by the freemen of the colony.[69] The first meeting of the General Court consisted of exactly eight men. They decided that the governor and deputy should be elected by the assistants, in violation of the charter; under these rules, Winthrop was elected governor three times. The general court admitted a significant number of settlers, but also established a rule requiring all freemen to be local church members.[70] The colony saw a large influx of immigrants in 1633 and 1634, following the appointment of strongly anti-Puritan William Laud as Archbishop of Canterbury.[71]

When the 1634 election was set to take place, delegations of freemen sent by the towns insisted on seeing the charter, from which they learned that the colony's lawmaking authority, the election of governor, and the election of the deputy all rested with the freemen, not with the assistants. Winthrop acceded on the point of the elections, which were thereafter conducted by secret ballot by the freemen, but he also observed that lawmaking would be unwieldy if conducted by the relatively large number of freemen. A compromise was reached in which each town would select two delegates to send to the general court as representatives of its interests.[72] In an ironic twist, Thomas Dudley, an opponent of popular election, won the 1634 election for governor, with Roger Ludlow as deputy.[73] Winthrop graciously invited his fellow magistrates to dinner, as he had done after previous elections.[74]

In the late 1630s, the seeming arbitrariness of judicial decisions led to calls for the creation of a body of laws that would bind the opinions of magistrates. Winthrop opposed these moves, and used his power to repeatedly stall and obstruct efforts to enact them.[75] His opposition was rooted in a strong belief in the common law tradition and the desire, as a magistrate, to have flexibility in deciding cases on their unique circumstances. He also pointed out that adoption of written laws "repugnant to the laws of England" was not allowed in the charter, and that some of the laws to be adopted likely opposed English law.[76] The Massachusetts Body of Liberties was formally adopted during Richard Bellingham's governorship in 1641.[75] Some of the laws enacted in Massachusetts were cited as reasons for vacating the colonial charter in 1684.[77]

In the 1640s, constitutional issues arose concerning the power of the magistrates and assistants. In a case involving an escaped pig, the assistants ruled in favor of a merchant who had allegedly taken a widow's errant animal. She appealed to the general court, which ruled in her favor. The assistants then asserted their right to veto the general court's decision, sparking the controversy. Winthrop argued that the assistants, as experienced magistrates, must be able to check the democratic institution of the general court, because "a democracy is, amongst most civil nations, accounted the meanest and worst of all forms of government."[2]

Winthrop became the focus of allegations about the arbitrary rule of the magistrates in 1645, when John was formally charged with interfering with local decisions in a case involving the Hingham militia.[78] The case centered around the disputed appointment of a new commander, and a panel of magistrates headed by Winthrop had several parties imprisoned on both sides of the dispute, pending a meeting of the court of assistants. Peter Hobart, the minister in Hingham and one of several Hobarts on one side of the dispute, vociferously questioned the authority of the magistrates and railed against Winthrop specifically for what he characterized as arbitrary and tyrannical actions. Winthrop defused the matter by stepping down from the bench to appear before it as a defendant. He successfully defended himself, pointing out that he had not acted alone, and also that judges are not usually criminally culpable for errors that they make on the bench. He also argued that the dispute in Hingham was serious enough that it required the intervention of the magistrates.[79] Winthrop was acquitted and the complainants were fined.[80]

One major issue that Winthrop was involved in occurred in 1647, when a petition was submitted to the general court concerning the limitation of voting rights to freemen who had been formally admitted to a local church. Winthrop and the other magistrates rejected the appeal that "civil liberty and freedom be forthwith granted to all truly English", and even fined and imprisoned the principal signers of the petition.[81] William Vassal and Robert Child, two of the signatories, pursued complaints against the Massachusetts government in England over this and other issues.[82]

Religious controversies

In 1634 and 1635, Winthrop served as an assistant, while the influx of settlers brought first John Haynes and then Henry Vane to the governorship. Haynes, Vane, Anne Hutchinson, and pastors Thomas Hooker and John Wheelwright all espoused religious or political views that were at odds with those of the earlier arrivals, including Winthrop.[83] Hutchinson and Wheelwright subscribed to the Antinomian view that following religious laws was not required for salvation, while Winthrop and others believed in a more Legalist view. This religious rift is commonly called the Antinomian Controversy, and it significantly divided the colony; Winthrop saw the Antinomian beliefs as a particularly unpleasant and dangerous heresy.[84] By December 1636, the dispute reached into colonial politics, and Winthrop attempted to bridge the divide between the two factions. He wrote an account of his religious awakening and other theological position papers designed to harmonize the opposing views. (It is not known how widely these documents circulated, and not all of them have survived.) In the 1637 election, Vane was turned out of all offices, and Dudley was elected governor.[85]

Dudley's election did not immediately quell the controversy. First John Wheelwright and later Anne Hutchinson were put on trial, and both were banished from the colony.[86] (Hutchinson and others founded the settlement of Portsmouth on Rhode Island; Wheelwright founded first Exeter, New Hampshire and then Wells, Maine in order to be free of Massachusetts rule.)[87][88] Winthrop was active in arguing against their supporters, but Shepard criticized him for being too moderate, claiming that Winthrop should "make their wickedness and guile manifest to all men that they may go no farther and then will sink of themselves."[86] Hooker and Haynes had left Massachusetts in 1636 and 1637 for new settlements on the Connecticut River (the nucleus of the Connecticut Colony);[89] Vane left for England after the 1637 election, suggesting that he might seek a commission as a governor general to overturn the colonial government.[90] (Vane never returned to the colony, and became an important figure in Parliament before and during the English Civil Wars; he was beheaded after the Restoration.)[91]

In the aftermath of the 1637 election, the general court passed new rules on residency in the colony, forbidding anyone from housing newcomers for more than three weeks without approval from the magistrates. Winthrop vigorously defended this rule against protests, arguing that Massachusetts was within its rights to "refuse to receive such whose dispositions suit not with ours".[92] Ironically, some of those who protested the policy had been in favor of banishing Roger Williams in 1635.[92] Winthrop was then out of office, and he had a good relationship with Williams. The magistrates ordered Williams' arrest, but Winthrop warned him, making possible his flight which resulted in the establishment of Providence Plantations.[93][c] Winthrop and Williams later had an epistolary relationship in which they discussed their religious differences.[94]

Indian policy

Winthrop's attitude toward the local Indian populations was generally one of civility and diplomacy. He described an early meeting with one local chief:

Chickatabot came with his [chiefs] and squaws, and presented the governor with a hogshead of Indian corn. After they had all dined, and had each a small cup of sack and beer, and the men tobacco, he sent away all his men and women (though the governor would have stayed them in regard of the rain and thunder.) Himself and one squaw and one [chief] stayed all night; and being in English clothes, the governor set him at his own table, where he behaved himself as soberly ... as an Englishman. The next day after dinner he returned home, the governor giving him cheese, and pease, and a mug, and other small things.[95]

The colonists generally sought to acquire title to the lands that they occupied in the early years,[96] although they also practiced a policy that historian Alfred Cave calls vacuum domicilium (empty of inhabitants): if land is not under some sort of active use, does not have fixed habitation, structures, or fences, it was considered to be free for the taking.[97][98] This also meant that lands, which were only used seasonally by the Indians (e.g., for fishing or hunting) and were empty otherwise, could be claimed. According to Alfred Cave, Winthrop asserted that the rights of "more advanced" peoples superseded the rights of the Indians.[99]

However, cultural differences and trade issues between the colonists and the Indians meant that clashes were inevitable, and the Pequot War was the first major conflict in which the colony engaged. Winthrop sat on the council which decided to send an expedition under John Endecott to raid Indian villages on Block Island in the war's first major action.[100] Winthrop's communication with Williams encouraged Williams to convince the Narragansetts to side with the colonists against the Pequots, who were their traditional enemies.[101] The war ended in 1637 with the destruction of the Pequots as a tribe, whose survivors were scattered into other tribes or shipped to the West Indies.[102]

Slavery and the slave trade

In the aftermath of the Pequot War of 1636–38, many of the captured Pequots warriors were shipped to the West Indies as slaves. Winthrop kept one male and two female Pequots as slaves.[103][104]

In 1641, the Massachusetts Body of Liberties was enacted, codifying rules about slavery, among many other things. Winthrop was a member of the committee which drafted the code, but his exact role is not known because records of the committee have not survived. C. S. Manegold writes that Winthrop was opposed to the Body of Liberties because he favored a common law approach to legislation.[105]

Trade and diplomacy

Rising tensions in England culminated in a civil war and led to a significant reduction in the number of people and provisions arriving in the colonies. The colonists consequently began to expand trade and interaction with other colonies, non-English as well as English. This led to trading ventures with other Puritans on Barbados, a source of cotton, and with the neighboring French colony of Acadia.[106]

French Acadia covered the eastern half of present-day Maine, as well as New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. It was embroiled in a minor civil war between competing administrators; English colonists began trading with Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour in 1642, and his opponent Charles de Menou d'Aulnay warned Boston traders away from de la Tour's territories. In June 1643, de la Tour came to Boston and requested military assistance against assaults by d'Aulnay.[107] Governor Winthrop refused to provide official assistance, but allowed de la Tour to recruit volunteers from the colony for service.[108]

This decision brought on a storm of criticism, principally from the magistrates of Essex County, which was geographically closest to the ongoing dispute.[109] John Endecott was particularly critical, noting that Winthrop had given the French a chance to see the colonial defenses.[108] The 1644 election became a referendum on Winthrop's policy, and he was turned out of office.[110] The Acadian dispute was eventually resolved with d'Aulnay as the victor. In 1646, Winthrop was again in the governor's seat when d'Aulnay appeared in Boston and demanded reparations for damage done by the English volunteers. Winthrop placated the French governor with the gift of a sedan chair, originally given to him by an English privateer.[111]

Property and family

In addition to his responsibilities in the colonial government, Winthrop was a significant property owner. He owned the Ten Hills Farm, as well as land that became the town of Billerica, Governors Island in Boston Harbor (now the site of Logan International Airport), and Prudence Island in Narragansett Bay.[112] He also engaged in the fur trade in partnership with William Pynchon, using the ship Blessing of the Bay.[113] Governors Island was named for him and remained in the Winthrop family until 1808, when it was purchased for the construction of Fort Winthrop.[114]

The farm at Ten Hills suffered from poor oversight on Winthrop's part. The steward of the farm made questionable financial deals that caused a cash crisis for Winthrop. The colony insisted on paying him his salary (which he had refused to accept in the past) as well as his expenses while engaged in official duties. Private subscriptions to support him raised about £500 and the colony also granted his wife 3,000 acres (12 km2) of land.[115]

His wife Margaret arrived on the second voyage of the Lyon in 1631, but their baby daughter Anne died during the crossing. Two more children were born to the Winthrops in New England before Margaret died on June 14, 1647.[116][117] Winthrop married his fourth wife Martha Rainsborough some time after December 20, 1647, and before the birth of their only child in 1648. She was the widow of Thomas Coytmore and sister of Thomas and William Rainborowe.[118] Winthrop died of natural causes on March 26, 1649, and is buried in what is now called the King's Chapel Burying Ground in Boston.[119] He was survived by his wife Martha and five sons.[120]

Writings and legacy

Winthrop rarely published and his literary contribution was relatively unappreciated during his time, yet he spent his life continually producing written accounts of historical events and religious manifestations. His major contributions to the literary world was The History of New England (1630–1649, also known as The Journal of John Winthrop), which remained unpublished until the late 18th century.

The History of New England

Winthrop kept a journal of his life and experiences, starting with the voyage across the Atlantic and continuing through his time in Massachusetts, originally written in three notebooks. His account has been acknowledged as the "central source for the history of Massachusetts in the 1630s and 1640s".[121] The first two notebooks were published in 1790 by Noah Webster. The third notebook was long thought lost but was rediscovered in 1816, and the complete journals were published in 1825 and 1826 by James Savage as The History of New England from 1630 to 1649. By John Winthrop, Esq. First Governor of the Colony of the Massachusetts Bay. From his Original Manuscripts. The second notebook was destroyed in a fire at Savage's office in 1825; the other two volumes now belong to the Massachusetts Historical Society.[122] Richard Dunn and Laetitia Yeandle produced a modern transcription of the diaries in 1996, combining new analysis of the surviving volumes and Savage's transcription of the second notebook.[123]

The journal began as a nearly day-to-day recounting of the ocean crossing. As time progressed, he made entries less frequently and wrote at a greater length so that, by the 1640s, the work began to take the shape of a history.[124] Winthrop wrote primarily of his private accounts: his journey from England, the arrival of his wife and children to the colony in 1631, and the birth of his son in 1632. He also wrote profound insights into the nature of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and nearly all important events of the day.[125] The majority of his early journal entries were not intended to be literary, but merely observations of early New England life. Gradually, the focus of his writings shifted from his personal observations to broader spiritual ideologies and behind-the-scenes views of political matters.[126]

Other works

Winthrop's earliest publication was likely The Humble Request of His Majesties Loyal Subjects (London, 1630), which defended the emigrants' physical separation from England and reaffirmed their loyalty to the Crown and Church of England. This work was republished by Joshua Scottow in the 1696 compilation MASSACHUSETTS: or The first Planters of New-England, The End and Manner of their coming thither, and Abode there: In several EPISTLES.[127]

In addition to his more famous works, Winthrop produced a number of writings, both published and unpublished. While living in England, he articulated his belief "in the validity of experience" in a private religious journal known as his Experiencia.[128] He wrote in this journal intermittently between 1607 and 1637 as a sort of confessional, very different in tone and style from the Journal.[129] Later in his life, he wrote A Short Story of the rise, reign, and ruine of the Antinomians, Familists and Libertines, that Infected the Churches of New England which described the Antinomian controversy surrounding Anne Hutchinson and other in 1636 and 1637. The work was first published in London in 1644.[130] At the time of its publication, there was much discussion about the nature of church governance, and the Westminster Assembly of Divines had recently begun to meet. The evidence which it presented was seen by supporters of Congregationalism as proving the book's worth, and by opponents as proving its failings.[131] In some of its editions, it was adapted by opponents of Henry Vane, who had become a leading Independent political leader in the discussion. Vane's opponents sought to "tie Toleration round the neck of Independency, stuff the two struggling monsters into one sack, and sink them to the bottom of the sea."[132]

According to biographer Francis Bremer, Winthrop's writings echoed those of other Puritans which "were efforts both to discern the divine pattern in events and to justify the role [which] New Englanders believed themselves called to play."[128]

Legacy

Winthrop was historically credited for writing "A Modell of Christian Charitie" and its reference to a "city upon a hill", imagery that became an enduring symbol in American political discourse.[133] Many American politicians have cited him in their writings or speeches, going back to revolutionary times. Winthrop's reputation suffered in the late 19th and early 20th century, when critics pointed out the negative aspects of Puritan rule, including Nathaniel Hawthorne and H. L. Mencken, and leading to modern assessments of him as a "lost Founding Father". Political scientist Matthew Holland argues that Winthrop "is at once a significant founding father of America's best and worst impulses", with his calls for charity and public participation offset by what Holland views as rigid intolerance, exclusionism, and judgmentalism.[134]

Winthrop gave a speech to the General Court in July 1645, stating that there are two kinds of liberty: natural liberty to do as one wished, "evil as well as good," a liberty that he believed should be restrained; and civil liberty to do good. Winthrop strongly believed that civil liberty was "the proper end and object of authority", meaning that it was the duty of the government to be selfless for the people and promote justice instead of promoting the general welfare.[135] He supported this point of view by his actions, such as when he passed laws requiring the heads of households to make sure that their children and servants received proper education, and for support of teachers from public funds.[9] Winthrop's actions were for the unity of the colony because he believed that nothing was more crucial of a colony than working as a single unit that wouldn't be split by any force, such as with the case of Anne Hutchinson.[9] He was a leader respected by many, even Richard Dummer, a principal Hutchinsonian disarmed for his activities, who gave 100 pounds to him.[136]

Many modern politicians's speeches refer to writings attributed to Winthrop, such as those of John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, Michael Dukakis, and Sarah Palin.[137][138] Reagan described Winthrop as "an early 'Freedom Man'" who came to America "looking for a home that would be free."[139]

Winthrop is a major character in Catharine Sedgwick's 1827 novel Hope Leslie, set in colonial Massachusetts.[140] He also makes a brief appearance in Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter in the chapter entitled "The Minister's Vigil."[141]

Winthrop's descendants number thousands today. His son John was the first governor of the Saybrook Colony, and later generations of his family continued to play an active role in New England politics well into the 19th century. Twentieth century descendants include former US Senator from Massachusetts and former Secretary of State John Kerry, educator Charles William Eliot, and Downton Abbey creator, Julian Fellowes.[142] The towns of Winthrop, Massachusetts, and Winthrop, Maine, are named in his honor.[143][144] Winthrop House at Harvard University and Winthrop Hall at Bowdoin College[145] are named in honor of him and of his descendant John Winthrop, who briefly served as President of Harvard.[146]

He is also the namesake of squares in Boston (downtown and in Charlestown), Cambridge, and Brookline.[citation needed] The Winthrop Building on Water Street in Boston was built on the site of one of his homes and is one of the city's first skyscrapers.[147] NYU Langone Hospital in Mineola, New York was named Winthrop Hospital since 1986 named for Winthrop's descendant, Robert Winthrop, a retired investment banker, and long time patron and volunteer of the hospital.[148]

A statue of Winthrop by Richard Greenough is one of Massachusetts' two statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection, Capitol in Washington D.C.[149]

Not long after the death and funeral of Winthrop, early American poet Benjamin Tompson wrote a Funeral Tribute in Winthrop's honor, which appeared in his work, New-Englands Tears, in 1676.[150][151] The Tribute was also printed as a broadsheet and circulated in Boston that same year.[citation needed][d]

Notes

- ^ a b In the Julian calendar, then in use in England, the year began on March 25. To avoid confusion with dates in the Gregorian calendar, then in use in other parts of Europe, dates between January and March were often written with both years. Dates in this article are in the Julian calendar unless otherwise noted.

- ^ Samuel became a governor of Antigua.

- ^ Providence Plantation later united with the settlements on Rhode Island (now called Aquidneck Island) to create the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.

- ^ The text of the funeral tribute to Winthrope can be read in White, 1980, pages 109–110.[151]

Citations

- ^ Ward 1961, p. 410

- ^ a b Morison, p. 92

- ^ Moore, p. 237

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 403, notes the distinction that not all of the Winthrop children were recorded in the Edwardstone parish register.

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 67

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 70

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 68

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 73

- ^ a b c d e Bremer, Francis (2004). "Winthrop, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29778. Retrieved October 11, 2014. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 79

- ^ "Winthrop, John (WNTP603J)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 82

- ^ Andrew Thrush and John P. Ferris, 'SPRING, Sir William (1588–1638)', The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1604–1629 (2010), from History of Parliament online (Accessed March 11, 2014).

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 83

- ^ Bremer (2003), pp. 84, 90

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 88

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 89

- ^ Bremmer, Francis (2004). "Winthrop, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29778. Retrieved October 11, 2014. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Moore, pp. 268–270

- ^ a b Mayo (1948), pp. 59–61

- ^ a b Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, p. 2

- ^ a b Bremer (2003), p. 91

- ^ Bremer (2003), pp. 98–100

- ^ Morison, p. 53

- ^ Morison, p. 54

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 106

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 107

- ^ Bremer (2003), pp. 107–109

- ^ Morison, p. 59

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 96

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 97

- ^ Morison, p. 60

- ^ a b c Bremer (2003), p. 103

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 101

- ^ Bremer (2003), pp. 112–113

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 115

- ^ Bremer (2003), pp. 117–125

- ^ a b c Morison, p. 64

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 138

- ^ Morison, p. 12

- ^ Morison, pp. 28–29

- ^ Morison, pp. 31–34

- ^ Morison, p. 35

- ^ Bremer (2003), pp. 153–155

- ^ Manegold, pp. 8–12

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 156

- ^ Bremer (2003), pp. 157–158

- ^ Morison, p. 69

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 161

- ^ Moore, p. 277

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 164

- ^ Bremer (2003), pp. 162, 203

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 169

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 162

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 168

- ^ "Arms of the Founders and Leaders of European Settlements in the Present-Day United States". American Heraldry Society. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- ^ Bremer (2003), pp. 169, 188–189

- ^ Holland, p. 29

- ^ McGann (2019, pp. 28–31, 43–44); Van Engen (2020, p. 296).

- ^ Bremer (2003), pp. 175–179

- ^ Mayo (1936), pp. 54–58

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 104

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 205

- ^ Manegold, pp. 26–27

- ^ Hart, p. 1:184

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 213

- ^ Morison, p. 91

- ^ Jones, p. 251

- ^ Morison, p. 84

- ^ Morison, p. 85

- ^ Morison, p. 82

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 218

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 243

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 241

- ^ a b Bremer (2003), p. 305

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 306

- ^ Osgood, p. 3:334

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 361

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 362

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 363

- ^ Hart, pp. 1:122–123

- ^ Moore, p. 263

- ^ Bremer (2003), pp. 281–285

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 285

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 291

- ^ a b Bremer (2003), p. 293

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 299

- ^ Golson, pp. 61–62

- ^ Moore, pp. 300–302

- ^ Winship, p. 9

- ^ Moore, pp. 321–333

- ^ a b Bremer (2003), p. 294

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 251

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 252

- ^ Moore, pp. 246–247

- ^ Moseley, p. 52

- ^ Alfred A. Cave. Canaanites in a Promised Land: The American Indian and the Providential Theory of Empire, American Indian Quarterly, vok. 12, No. 4 (Autumn, 1988), pp. 277–297. JSTOR 1184402

- ^ Paul Corcoran. John Locke on the Possession of Land: Native Title vs. the ‘Principle ’ of Vacuum domicilium, Proceedings, Australasian Political Studies Association Annual Conference, 2007

- ^ Cave, pp. 35–36

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 267

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 269

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 271

- ^ Manegold (January 18, 2010), New England's scarlet 'S' for slavery; Manegold (2010), Ten Hills Farm: The Forgotten History of Slavery in the North, 41–42 Harper (2003), Slavery in Massachusetts; Bremer (2003), p. 314

- ^ Gallay, Alan. (2002) The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670–1717. Yale University Press: New York. ISBN 0-300-10193-7, pp. 7, 299–320

- ^ Manegold (January 18, 2010), New England's scarlet 'S' for slavery; Manegold (2010), Ten Hills Farm: The Forgotten History of Slavery in the North, 41–42 Harper (2003), Slavery in Massachusetts; Bremer (2003), pp. 304, 305, 314

- ^ Moseley, p. 99

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 343

- ^ a b Bremer (2003), p. 344

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 345

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 346

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 347

- ^ Moore, pp. 264–265

- ^ Bremer (2003), pp. 252–253

- ^ Stanhope and Bacon, pp. 122–123

- ^ Moore, p. 264

- ^ Anderson, p. 2039

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 187

- ^ Anderson, p. 2040

- ^ Moore, p. 265

- ^ Moore, pp. 271–272

- ^ Winthrop et al., p. xi

- ^ Winthrop et al., p. xii

- ^ Winthrop et al.

- ^ Winthrop et al., p. xvi

- ^ "John Winthrop". Biography in Context. Encyclopedia of World Biography. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ Winthrop et al., p. xxvii

- ^ Winthrop, John; Dudley, Thomas; Allin, John; Shepard, Thomas; Cotton, John; Scottow, Joshua (January 1696). "Massachusetts: or The First Planters of New-England, The End and Manner of Their Coming Thither, and Abode There: In Several Epistles (1696)". Joshua Scottow Papers. University of Nebraska, Lincoln. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ a b Bremer (1984)

- ^ Winthrop et al., p. xviii

- ^ Schweninger, pp. 47–66

- ^ Hall, p. 200

- ^ Moseley, p. 125

- ^ Bremer (2003, p. xv); McGann (2019, pp. 28–31, 43–44); Van Engen (2020, p. 296).

- ^ Holland, p. 2

- ^ "John Winthrop". Biography in context. Encyclopedia of World Biography. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- ^ Cohen, Charles. "Winthrop, John". American National Biography Online. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. xv

- ^ Kennedy, p. 48

- ^ Moseley, p. 7

- ^ Sedgwick

- ^ Hawthorne

- ^ Roberts, Gary Boyd. "Notable Descendants of Governor Thomas Dudley". New England Historic Genealogical Society. Archived from the original on December 10, 2010. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ "About Winthrop, Massachusetts". Town of Winthrop. Archived from the original on December 24, 2014. Retrieved February 17, 2011.

- ^ Howard and Crocker, p. 2:72

- ^ "Winthrop Hall – Library – Bowdoin College". Archived from the original on January 13, 2014. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- ^ "History of Winthrop House". Winthrop House. Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved February 17, 2011.

- ^ "Massachusetts Cultural Resource Inventory: Winthrop Building". Retrieved April 13, 2012.

- ^ Ketcham, Diane (July 16, 1985). "Long Island Journal: Winthrop-University Hospital". New York Times. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ Murdock, Myrtle Chaney, National Statuary Hall in the Nation's Capitol, Monumental Press, Inc., Washington, D.C., 1955 pp. 44–45

- ^ Tompson (1676), p. 7

- ^ a b White (1980), p. viii, 109–110, 119

Bibliography

- Anderson, Robert Charles (1995). The Great Migration Begins: Immigrants to New England, 1620–1633. Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 978-0-88082-120-9. OCLC 42469253.

- Bremer, Francis J (1984). Wilson, Clyde Norman (ed.). "John Winthrop". Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 30: American Historians, 1607–1865. Detroit: Gale Research. Gale Group link.

- Bremer, Francis (2003). John Winthrop: America's Forgotten Founder. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514913-5. OCLC 237802295.

- Cave, Alfred (1996). The Pequot War. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 978-1-55849-029-1. OCLC 33405267.

- Dunn, Richard (1962). Puritans and Yankees: the Winthrop Dynasty of New England, 1630–1717. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. OCLC 187083766.

- Findling, John E; Thackeray, Frank W (2000). Events That Changed America Through the Seventeenth Century. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29083-1. OCLC 43370295.

- Jones, Augustine (1900). The Life and Work of Thomas Dudley, the Second Governor of Massachusetts. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin. OCLC 123194823.

- Kennedy, Sheila; Schultz, David (2010). American Public Service: Constitutional and Ethical Foundations. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-0-7637-6002-1. OCLC 587153866.

- Litke, Justin B., "Varieties of American Exceptionalism: Why John Winthrop Is No Imperialist," Journal of Church and State, 54 (Spring 2012), 197–213.

- Manegold, C. S (2010). Ten Hills Farm: The Forgotten History of Slavery in the North. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13152-8. OCLC 320801223.

- Manegold, C. S (January 18, 2010). "New England's scarlet 'S' for slavery". The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- Mayo, Lawrence Shaw (1936). John Endecott. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. OCLC 1601746.

- Mayo, Lawrence Shaw (1948). The Winthrop Family in America. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society. OCLC 2411980.

- McGann, Jerome (Spring 2019). "'Christian Charity,' A Sacred American Text: Fact, Truth, Method". Textual Cultures. 12 (1): 27–52. doi:10.14434/textual.v12i1.27151. JSTOR 26662803.

- Moore, Jacob Bailey (1851). Lives of the Governors of New Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay. Boston: C. D. Strong. p. 237. OCLC 11362972.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1981) [1930]. Builders of the Bay Colony. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 0-930350-22-7.

- Moseley, James (1992). John Winthrop's World: History as a Story, the Story as History. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-13530-0. OCLC 26012952.

- Osgood, Herbert Levi (1907). The American Colonies in the Seventeenth Century. New York: Macmillan. p. 334. OCLC 768506.

- Pease, Donald E (2009). The New American Exceptionalism. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-2782-0. OCLC 370610705.

- Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Second Series, Volume VI. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society. 1891. OCLC 1695300.

- Schweninger, Lee (1990). John Winthrop. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-7547-1. OCLC 20131700.

- Sedgwick, Catharine Maria (1842). Hope Leslie, or, Early Times in the Massachusetts. New York: Harper & Brothers. OCLC 7910332.

- Stanhope, Edward; Bacon, Edwin Monroe (1886). Boston Illustrated. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin. OCLC 79184535.

- Tompson, Benjamin (1676). New-Englands Tears for her present miseries.

- Van Engen, Abram C. (2020). City on a Hill: A History of American Exceptionalism. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300252316.

- Winship, Michael (2002). Making Heretics: Militant Protestantism and Free Grace in Massachusetts, 1636–1641. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08943-0. OCLC 470517711.

- Winthrop, John; Dunn, Richard; Savage, James; Yeandle, Laetitia (1996). The Journal of John Winthrop, 1630–1649. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-48425-2. OCLC 185405449.

- White, Peter (1980). Benjamin Tompson, colonial bard : a critical edition. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 9780271002507.

Further reading

- Dunn, Richard (April 1984). "John Winthrop Writes His Journal". The William and Mary Quarterly. Third Series. 41 (2): 186–212. doi:10.2307/1919049. JSTOR 1919049.

{cite journal}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Winthrop, John (1790). A Journal of the Transactions and Occurrences in the Settlement of Massachusetts and the Other New-England Colonies, From the Year 1630 to 1644. Hartford, CT: Elisha Babcock. OL 24406790M. The 1790 edition containing two volumes of Winthrop's journal.

- John Winthrop (1825). The history of New England from 1630 to 1649. With notes by J. Savage. Vol. 1. Boston: Phelps and Farnham. OCLC 312030996.

- John Winthrop (1826). The history of New England from 1630 to 1649. With notes by J. Savage. Vol. 2. James Savage's 1825–26 edition of Winthrop's journal.

- Winthrop, John; Hosmer, James Kendall (1908). Winthrop's journal, "History of New England" : 1630–1649. Vol. I. New York : Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Winthrop, John; Hosmer, James Kendall (1908). Winthrop's journal, "History of New England" : 1630–1649. Vol. II. New York : Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Ward, Harry, ed. (1961). The United Colonies of New England 1643–90. Vantage Press.

External links

- "Arbitrary Government Described and the Government of the Massachusetts Vindicated from that Aspersion" (1644 pamphlet by Winthrop)

- "A Modell of Christian Charity" (text of Winthrop's 1630 sermon)

- The Winthrop Society

- EDSITEment lesson plan about John Winthrop's Model of Christian Charity

- Works by or about John Winthrop at the Internet Archive

- Works by John Winthrop at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)