John Hope, 7th Earl of Hopetoun

The Marquess of Linlithgow | |

|---|---|

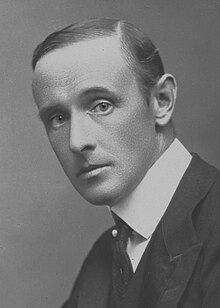

Hope in 1902 | |

| 1st Governor-General of Australia | |

| In office 1 January 1901 – 17 July 1902 | |

| Monarchs | Victoria Edward VII |

| Prime Minister | Edmund Barton |

| Preceded by | New position |

| Succeeded by | Lord Tennyson |

| 7th Governor of Victoria | |

| In office 28 November 1889 – 12 July 1895 | |

| Premier | Duncan Gillies James Munro William Shiels James Patterson George Turner |

| Preceded by | Lord Loch |

| Succeeded by | Lord Brassey |

| Secretary for Scotland | |

| In office 2 February 1905 – 4 December 1905 | |

| Prime Minister | Arthur Balfour |

| Preceded by | Andrew Murray |

| Succeeded by | John Sinclair |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 25 September 1860 South Queensferry, West Lothian, Scotland |

| Died | 29 February 1908 (aged 47) Pau, France |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse | |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation | Statesman, aristocrat |

John Adrian Louis Hope, 1st Marquess of Linlithgow, 7th Earl of Hopetoun, KT, GCMG, GCVO, PC (25 September 1860 – 29 February 1908) was a British aristocrat and statesman who served as the first governor-general of Australia, in office from 1901 to 1902. He was previously Governor of Victoria from 1889 to 1895.

Hopetoun was born into the Scottish nobility, and succeeded his father as Earl of Hopetoun at the age of 12. He attended Eton College and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, but opted not to pursue a full-time military career. Hopetoun sat with the Conservative Party in the House of Lords, and became a Lord-in-waiting in 1885 and Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1887. He was appointed Governor of Victoria at the age of 29, and had a successful tenure in a time of political and economic instability.

After returning to England in 1895, Hopetoun served in Lord Salisbury's cabinet as Paymaster General and Lord Chamberlain. The announcement of his appointment to the new governorship-general in July 1900 was met with praise. However, he arrived in Australia ill-informed about the political aspects of federation, and his decision to call on William Lyne to form a caretaker government became known as the "Hopetoun Blunder". Lyne, who had campaigned against federation, had little support from the political establishment, and Hopetoun was forced to turn to Edmund Barton to serve as Australia's first prime minister. His relationship with Barton once in office was civil, although his interferences in political matters were not well received.

Hopetoun was popular with the general public, but developed a reputation for flamboyance and ostentation. The Cookatoo Inn in Surry Hills was revamped and renamed the Hopetoun Hotel in 1901 in his honour.[1] His desire for a large expenses allowance was rebuffed by parliament, and he consequently relinquished office in July 1902. He was granted a marquessate upon his return to England, and thereafter withdrew from public life, except for a brief term as Secretary of State for Scotland in 1905. He died in France at the age of 47, after several years of ill health. Hopetoun's term as governor-general is generally regarded as a failure, and his successors generally avoided emulating his extravagance. Only Lord Denman held the position at a younger age.

Early life and career

Hope was born at South Queensferry, West Lothian, Scotland, the eldest son of John Hope, 6th Earl of Hopetoun, and the former Ethelred Anne Birch-Reynardson. He was educated at Eton College and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, where he passed out in 1879. However, he chose not to join the regular army upon graduation. He later explained "the affairs of the family estate, to which I succeeded at 13, seemed to call for my personal attention".[2] Subsequently, he devoted his attentions to managing the more than seventeen thousand hectares (42,500 acres) of family estate located around the Firth of Forth.

He married, in London on 18 October 1886, Hersey Alice Eveleigh-de Moleyns (formerly Mullins), a Scots-born Irish aristocrat (daughter of the 4th Baron Ventry) then aged 19. They had two sons and a daughter; a second daughter died in infancy.[3] Their elder son, Victor, became Viceroy and Governor-General of India (1936–43), after having declined the governorship of Madras and the governor-generalship of Australia.

In 1883, Hopetoun became Conservative whip in the House of Lords and served as a Lord in Waiting to Queen Victoria from June 1885 to January 1886 and August 1886 to August 1889. From 1887 to 1889 he was also appointed Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland.[3]

Governor of Victoria

In 1889 he was appointed Governor of Victoria (and additionally a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George),[4] where he served until 1895. His appointment came amid a general stylistic change in colonial governors. Reflecting "Britain's more flamboyant pride in Empire, Australian colonial governors began to display a new colour and ostentation".[5] Increased interest in Empire had spurred the appearance of young and wealthy aristocrats in place of previous career administrators.

Hopetoun's time as Governor was in keeping with the newly emerging style. He rapidly developed a reputation for lavish entertaining and spectacular vice-regal galas. Notwithstanding poor health and colonial astonishment at his habit of wearing hair-powder, his youthful enthusiasm for routine duties and his fondness for informal horseback tours won him many friends.[6][7]

Hopetoun's term coincided with a number of serious difficulties being faced by the colonies. The economic boom in the colony was reversed by the Great Crash in 1891, leading to a decade of depression, bank failures, industrial action and political instability. In contrast to the troubles faced during this period by other colonial governors, Hopetoun by most accounts handled this period ably and subsequently stayed in office for longer than the usual term. However, the reality of the 1890s was that colonial governors had lost much of their administrative and political power, instead assuming more figurative and representative roles.[8]

Hopetoun's term also coincided with the important years of the federation movement in Victoria. The economic crash and resultant political and social problems laid bare the inefficiencies of the colonial system and sparked renewed interest in an Australian federation. Hopetoun was an active supporter of the movement, appearing at numerous banquets and giving speeches in its favour. At one such banquet he even offered to return to Australia as their first governor-general should Federation be implemented. Upon leaving the governorship and returning to the United Kingdom in 1895, Hopetoun was a widely popular figure in Victoria and New South Wales.

Governor-General of Australia

After his return to the United Kingdom he was made a privy councillor,[9] was appointed Paymaster-General in the Salisbury government from 1895 to 1898, and then became Lord Chamberlain until 1900. 1900 also saw his appointment as a Knight of the Order of the Thistle and a Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order.[10]

The Australian colonies had agreed to federate, to form the Commonwealth of Australia from 1 January 1901. Hopetoun's popularity in Victoria and his friendship with leading Australian politicians made him an obvious choice to be the first Governor-General of Australia. In his submission to Queen Victoria in July 1900, Secretary of State for the Colonies Joseph Chamberlain described Hopetoun as "exceptionally qualified to discharge the duties of this important position with ability and efficiency" and stated that he would be "heartily welcomed" in Australia.[11] His strong ties with the Queen and with the incumbent British administration were also important to appointers in London. His appointment was approved by the Queen on 14 July 1900 and on 29 October letters patent were issued constituting the office and his own instructions.[12][13] Hopetoun arrived in Sydney on 15 December, via India, where he had caught typhoid fever and his wife malaria. Already in poor health during the preceding years in England, the trip further diminished Hopetoun's capacities.[6]

Intercolonial rivalries and traditional suspicions in Sydney of the excessive influence of Melbourne over national affairs were cause for some complex manoeuvres during Hopetoun's arrival. Though he was initially intended to arrive via Melbourne, local politicians insisted that the incoming Governor-General should disembark in Perth before going on to Sydney. Illness and misadventure following the Indian leg of the journey disrupted Hopetoun's tour and made the arduous arrival preparations difficult to complete. Lady Hopetoun had suffered a relapse of her condition during the trip across Australia, adding further to Hopetoun's personal troubles.

"Hopetoun Blunder"

Hopetoun's immediate task was to appoint a prime minister to form an interim government, which would take office on 1 January 1901. Since the first federal election was not scheduled to be held until March, he could not follow the usual convention of appointing the leader of the majority party in the House of Representatives. On 19 December 1900 Hopetoun chose to ask Sir William Lyne, the Premier of New South Wales, to form the first Commonwealth ministry. This caused great surprise amongst Australian and British politicians. In Australia, it had generally been assumed that Edmund Barton, a key leader of the Federation movement and drafter of the Constitution, would be offered the post in the first instance. The decision was defensible in terms of protocol, but it ignored the fact that Lyne had long strongly opposed federation until the passage of the referendums of 1899, and was unpopular with the leading federalist politicians.[14] Explanations for the appointment generally revolve around the precedent established by Canada, whereby the Premier of the senior colony, John A. Macdonald of Ontario, had formed the first federal Canadian government. Also, Barton was not a member of any parliament (he had resigned from the NSW Parliament earlier that year), and, although he had considerable political experience, he was considered in some quarters to be politically inept.[15] Lyne, on the other hand, was recognised as a tough and experienced politician.

However, it quickly became apparent that Lyne would not be able to form the first government. Alfred Deakin and other prominent politicians, particularly Victorian politicians, told Hopetoun they would not serve under Lyne. Lyne returned his commission on 24 December and Hopetoun sent for Edmund Barton, the leader of the federal movement and the man everybody believed was entitled to the post. Barton successfully assembled a cabinet, one that included Lyne, and it was sworn in by Hopetoun on the inauguration of the Commonwealth on New Year's Day, 1901. That afternoon, Hopetoun and the new government assembled at Government House, Sydney for the first meeting of the Federal Executive Council.

Hopetoun, wary that his actions would constitute important precedents for the new nation, generally followed pre-existing Canadian and British conventions in discharging his constitutional duties. Hopetoun was well-acquainted with many members of the first government and built a strong personal relationship with Barton, placing him in a position of respect and influence with the new federal politicians. He consulted regularly with the Prime Minister and with George Reid, the effective leader of the opposition, in the lead up to the first federal election in March 1901.

Conflict over the position

More problems soon arose though in establishing the new machinery of government. Hopetoun had brought his own Official Secretary, Captain Edward William Wallington, who handled all his communications with London. Wallington was highly experienced in Australian colonial administration, having advised many governors previously and earning a reputation as an expert in managing communications and relations with the Colonial Office in London. However Australians resented an Englishman being in charge of official business, and the fact that Wallington had no responsibility to the new Commonwealth parliament despite his influential governmental position.[6]

Other problems appeared with regard to the relationship between the new Governor-General and the continuing state governors. Disputes emerged between Hopetoun and several state governors—particularly South Australian governor Lord Tennyson, who would be Hopetoun's successor—over the Governor-General's right of access to dispatches and communiqués of the state governors. Questions of the independence of the states were raised and some fears of federal takeover of local affairs persisted during the disputes, until uneasy compromises were reached which saw some but not total subordination of state governors.[16] Hopetoun continued to struggle to diminish pre-existing local parochial sentiments within the states, though his position within the Commonwealth was much better publicised and secured after his co-ordination and hosting of the Royal Visit in 1901.[17] Tactful dealings with state governors and his strength at mediation helped secure that position in the early years of the Commonwealth as confidence in the new national entity was forged.

There was also resentment over the regal pomp upon which Hopetoun insisted in carrying out his role, and the expense which this entailed. Official visits to the states often incurred significant local expenses often not reimbursed by the Commonwealth, causing ructions in State-Federal relations until a resolution was reached in 1905, well after Hopetoun's term expired.[16]

Influence over the Barton government

Hopetoun also proved to be problematic as a public speaker in the new role. Though steering clear of any controversial subjects and stressing national unity and identity during his first months, in late 1901 and early 1902, he had committed several constitutional faux pas by publicly taking positions on political matters. Most notably in a speech to the Australian Natives' Association in January 1902, Hopetoun chose to discuss government policy towards the Boer War. He defended Barton's decision to commit support to the conflict, emphasised his own role in the making of the decision alongside Barton and professed a belief that it was Australia's duty to stand behind the imperial government in the war.

Though Barton and most of those who present were pleased with the patriotic speech, opposition leader George Reid quickly seized upon the issue as an example of inappropriate interference by the governor-general in political affairs that were the exclusive domain of parliament. A debate resulted in parliament which was generally critical, or at least tacitly disapproving, of Hopetoun's comments. The Bulletin summarised the opposition opinion in its editorial: "Since the day of the Governor-General's arrival, he has shown a disposition to assert, and Mr Barton to allow, powers utterly at variance with the rights of a self-governing people."[18]

Though most other opinion leaders did not go as far to state outright opposition to the governor-general's actions, they did spur important early debates as to the role of the governor-general. Barton himself admitted to some influence from the Governor-General: though initially Barton was reluctant to commit support to the Boer War, communications by Hopetoun to the Colonial Office in December 1901 revealed that Barton's position had been changed in favour of committing support and that change had most likely been driven by Hopetoun's efforts.[19]

Hopetoun also notably exercised influence over the content and passage of the Immigration Restriction Bill of 1901. Instructions from the Colonial Office revealed that in its original form, the bill was unacceptable to the British government, and Hopetoun was instructed to reserve Royal Assent until changes had been made. Hopetoun was left in a difficult position, as fears of immigration were rampant in Australia at the time and the bill was popular, notwithstanding the disapproval of the British government. A difficult period of private manoeuvring followed, after which Hopetoun was obliged to reserve assent on further amendments to the bill in the absence of instructions from London in an attempt to balance the interests of the Commonwealth and the Colonial Office. Eventually, important concessions were made by the Barton government and the bill was assented to by Hopetoun, although still not completely in line with imperial policy. Hopetoun's use of the assent power to negotiate changes in Commonwealth legislation was effective and skilfully deployed so as to avoid public confrontation over the issue.

An interesting friendship developed between Lord Hopetoun and the Melbourne anarchist and union pioneer, John 'Chummy' Fleming. In May 1901, Fleming protested against unemployment in Melbourne by rushing onto the Prince's Bridge to halt the governor-general's carriage. Hopetoun told the police not to interfere and listened to Fleming put the case for the unemployed. Out of this encounter came a friendship which endured after Hopetoun returned to England. According to some reports, Hopetoun is credited with pressuring the government to speed up government work projects.

Financial dispute and resignation

Hopetoun's time as governor-general came to an abrupt and embarrassing end after a dispute over the financial arrangements for the office emerged in mid-1902. The Constitutional Conventions of the 1890s had set the governor-general salary at a generous £10,000, equivalent to the Canadian office. Yet in Canada, extensive provisions had been made for travel, residence and entertaining, no provisions for which were made in the Australian case.

Discussion of this matter provoked traditional rivalries between New South Wales and Victoria, with both maintaining that the governor-general's seat should be in their respective state capitals. Eventually, houses in both states were provided for the governor-general's use and expectations were made that the viceroy would share his time between the two. However provision for the cost of maintaining two large residences, while planning the construction of a third in the future federal capital, became subject to the long-running dispute between the Commonwealth and the states.

Victoria and New South Wales both avoided the issue and failed to pass bills allowing for the governor-general's expenses while present in either state to be paid by the state itself. By the assumption of duties in 1901, Hopetoun still did not have a formal allowance approved for his expenses, but was privately assured by Barton that at least £8000 per annum would be at his disposal for the conduct of vice-regal duties.

Hopetoun was advised by the Colonial Office that he should limit his entertaining and expenses while the situation remained officially unresolved, but Hopetoun was by nature an extravagant figure in public life and significant resources were expended by Hopetoun travelling and hosting the Royal Visit. Barton meanwhile delayed on preparing a Commonwealth bill to cover the costs, stalling until mid-1902 to present the bill.

By this time, the euphoria of the royal tour had ended and political focus was on the still serious recession and drought that were straining the Australian economy. Barton's speech in favour of the £8000 allowance was weak, and every other speaker in the debate on the bill opposed the legislation, which was subsequently amended into an unrecognisable measure designed to recoup the expense of the royal visit. The parliament then made it clear that no allowance would be approved for the vice-regal activities beyond what salary was already paid. Hopetoun was shocked: he had already incurred very great costs out of his own pocket to cover the expense of the office, which had strained his personal fortunes.

Publicly humiliated by the parliamentary rebuke, still in relatively ill health, and now under financial duress; on 5 May Hopetoun announced to the Colonial Office his desire to be recalled from the position. The Colonial Office expressed displeasure at the actions of the Barton government and complied with the request.

Though newspapers and politicians were divided on who was to blame for the sudden resignation, and many tried to dissuade Hopetoun from his decision, ultimately it became clear that Hopetoun's perceptions that the governor-general would be a position analogous to the Viceroy of India or similar elaborate position were out of touch with public perceptions of the role. Hopetoun's attempts to serve Australia as a glamorous figure of the British Empire had brought him into conflict with domestic politics and ultimately were cause for the abrupt end to his term. Although Hopetoun's brief and frictional time in office revitalised some debate over whether the position should be a locally elected one, successors in the role quickly realised and conformed with the relative modesty which the position demanded and the system of British appointments continued.[20]

Hopetoun and his family left Australia from Brisbane on 17 July 1902, at which point Lord Tennyson, Governor of South Australia, took over as Administrator of the Government. Still very popular with the Australian public, there were elaborate and tearful farewell ceremonies in Melbourne and Sydney. Upon Hopetoun's return to Britain, King Edward VII recognised his service by bestowing upon him the title of Marquess of Linlithgow, in the county of Linlithgow or West Lothian, on 23 October 1902.[21] However among observers, and particularly Hopetoun himself, "there was little doubt that he had been less than successful in the great test of his public career".[22]

In the wake of his resignation, Alfred Deakin provided an explanatory editorial under alias for the British public in The Morning Post: "Our first Governor General may be said to have taken with him all the decorations and display and some of the anticipations that splendidly surrounded the inauguration of our national existence...we have...revised our estimate of high office, stripping it too hastily, but not unkindly, of its festal trappings. The stately ceremonial was fitting, but it has been completed."[23]

Later life

Though he greatly desired appointment to the Viceroyalty of India, Linlithgow was prevented from attaining the position by poor health and adverse political developments, though his son Victor, 2nd Marquess of Linlithgow, eventually assumed this role (after rejecting the post of Australian Governor-General in 1935) from 1936 to 1943. His grandson Lord Glendevon married the daughter of the English novelist W. Somerset Maugham.

In 1904 he accepted the position of President of the influential Scottish conservationist organisation the Cockburn Association, retaining the role until 1907.[24]

His final political appointment was to that of Secretary for Scotland during the last months of the ministry of Arthur Balfour in 1905. His political career failed to advance, and still plagued by poor health, he died suddenly of pernicious anaemia at Pau, France, on 29 February 1908.

Arms

|

|

References

- ^ "Hopetoun Hotel including Interior". NSW Government Office of Environment & Heritage. 22 October 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Cunneen 1983b, p. 3

- ^ a b Cunneen 2011

- ^ "No. 25974". The London Gazette. 13 September 1889. p. 4943.

- ^ Cunneen 1983b, p. 4

- ^ a b c Cunneen 1983a

- ^ Carroll 2004, p. 32

- ^ Cunneen 1983b, pp. 6–7

- ^ "No. 10694". The Edinburgh Gazette. 23 July 1895. p. 1101.

- ^ "No. 27237". The London Gazette. 12 October 1900. p. 6252.

- ^ Cunneen 1983b, p. 7

- ^ "Letters Patent constituting the office of Governor-General 29 October 1900 (UK)". Documenting a Democracy. Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ^ "Queen Victoria's Instructions to the Governor-General 29 October 1900 (UK)". Documenting a Democracy. Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ^ La Nauze 1957

- ^ Cunneen 1983b, p. 10

- ^ a b Wright 1970, pp. 219–225

- ^ Carroll 2004, p. 36

- ^ The Bulletin. 8 February 1902.

{cite news}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Cunneen 1983b, pp. 23–24

- ^ Carroll 2004, pp. 37–38

- ^ "No. 11456". The Edinburgh Gazette. 28 October 1902. p. 1061.

- ^ Cunneen 1983b, p. 35

- ^ Deakin, Alfred (2 September 1902). The Morning Post.

{cite news}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Historic Cockburn Association Office-Bearers".

- ^ Debrett's peerage, baronetage, knightage, and companionage. London : Dean & Son. 1903. p. 516, LINLITHGOW, MARQUESS OF. (Hope.). Retrieved 26 June 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Paul, James Balfour (1907). The Scots Peerage: Founded on Wood's Edition of Sir Robert Douglas's Peerage of Scotland containing an Historical and Genealogical Account of the Nobility of that Kingdom. Volume IV. Edinburgh : D. Douglas. pp. 484–505, Linlithgow. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Carroll, Brian (2004). Australia's Governors-General: From Hopetoun to Jeffery. Sydney: Rosenberg. ISBN 1-877058-21-1.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 730–731.

- Cunneen, Christopher (1983a). "Hopetoun, seventh Earl of (1860–1908)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 9. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943.

- Cunneen, Christopher (1983b). King's Men: Australia's Governors-General from Hopetoun to Isaacs. Sydney: G. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-86861-238-3.

- Cunneen, Christopher (January 2011) [2004]. "Hope, John Adrian Louis, seventh earl of Hopetoun and first marquess of Linlithgow (1860–1908)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33973. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- La Nauze, J. A. (1957). The Hopetoun Blunder: the Appointment of the First Prime Minister of the Commonwealth of Australia, December 1900. Carlton: Melbourne University Press.

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Hope, John Adrian Loius". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.

- Souter, Gavin (1976). Lion and Kangaroo: the Initiation of Australia, 1901–1919. Sydney: Collins.

- Torrance, David (2006). The Scottish Secretaries. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 978-1841584768.

- Wright, Don (1970). Shadow of Dispute: Aspects of Commonwealth-State Relations, 1901–1910. Canberra: Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-0708108109.