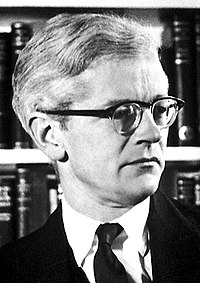

John Kendrew

John Kendrew | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | John Cowdery Kendrew 24 March 1917 Oxford, England |

| Died | 23 August 1997 (aged 80) Cambridge, England |

| Education | Clifton College, University of Cambridge |

| Known for | Haem-containing proteins |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Crystallography |

| Institutions | MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology Peterhouse, Cambridge Royal Air Force |

| Thesis | X-ray studies of certain crystalline proteins : the crystal structure of foetal and adult sheep haemoglobins and of horse myoglobin (1949) |

| Academic advisors | Max Perutz |

| Doctoral students | |

| Other notable students | James D. Watson (postdoc)[2] |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1941–1945 |

| Rank | Wing Commander (RAFVR) |

| Battles / wars | Second World War |

Sir John Cowdery Kendrew, CBE FRS[3] (24 March 1917 – 23 August 1997) was an English biochemist, crystallographer, and science administrator. Kendrew shared the 1962 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Max Perutz, for their work at the Cavendish Laboratory to investigate the structure of haem-containing proteins.

Education and early life

Kendrew was born in Oxford, son of Wilfrid George Kendrew, reader in climatology in the University of Oxford, and Evelyn May Graham Sandburg, art historian. After preparatory school at the Dragon School in Oxford, he was educated at Clifton College[4] in Bristol, 1930–1936. He attended Trinity College, Cambridge in 1936, as a Major Scholar, graduating in chemistry in 1939. He spent the early months of World War II doing research on reaction kinetics, and then became a member of the Air Ministry Research Establishment, working on radar. In 1940 he became engaged in operational research at the Royal Air Force headquarters; commissioned a squadron leader on 17 September 1941,[5] he was appointed an honorary wing commander on 8 June 1944,[6] and relinquished his commission on 5 June 1945.[7] He was awarded his PhD after the war in 1949.[8]

Research and career

During the war years, he became increasingly interested in biochemical problems, and decided to work on the structure of proteins.

Crystallography

In 1945 he approached Max Perutz in the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge. Joseph Barcroft, a respiratory physiologist, suggested he might make a comparative protein crystallographic study of adult and fetal sheep haemoglobin, and he started that work.

In 1947 he became a Fellow of Peterhouse; and the Medical Research Council (MRC) agreed to create a research unit for the study of the molecular structure of biological systems, under the direction of Sir Lawrence Bragg.[9] In 1954 he became a Reader at the Davy-Faraday Laboratory of the Royal Institution in London.

Crystal structure of myoglobin

Kendrew shared the 1962 Nobel Prize for chemistry with Max Perutz for determining the first atomic structures of proteins using X-ray crystallography. Their work was done at what is now the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge. Kendrew determined the structure of the protein myoglobin, which stores oxygen in muscle cells.[10]

In 1947 the MRC agreed to make a research unit for the Study of the Molecular Structure of Biological Systems. The original studies were on the structure of sheep haemoglobin, but when this work had progressed as far as was possible using the resources then available, Kendrew embarked on the study of myoglobin, a molecule only a quarter the size of the haemoglobin molecule. His initial source of raw material was horse heart, but the crystals thus obtained were too small for X-ray analysis. Kendrew realized that the oxygen-conserving tissue of diving mammals could offer a better prospect, and a chance encounter led to his acquiring a large chunk of whale meat from Peru. Whale myoglobin did give large crystals with clean X-ray diffraction patterns.[10] However, the problem still remained insurmountable, until in 1953 Max Perutz discovered that the phase problem in analysis of the diffraction patterns could be solved by multiple isomorphous replacement — comparison of patterns from several crystals; one from the native protein, and others that had been soaked in solutions of heavy metals and had metal ions introduced in different well-defined positions. An electron density map at 6 angstrom (0.6 nanometre) resolution was obtained by 1957, and by 1959 an atomic model could be built at 2 angstrom (0.2 nm) resolution.[11]

Later career

In 1963, Kendrew became one of the founders of the European Molecular Biology Organization; he also founded the Journal of Molecular Biology and was for many years its editor-in-chief. He became Fellow of the American Society of Biological Chemists in 1967 and honorary member of the International Academy of Science, Munich. In 1974, he succeeded in persuading governments to establish the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg and became its first director. He was knighted in 1974.[3] From 1974 to 1979, he was a Trustee of the British Museum, and from 1974 to 1988 he was successively Secretary General, Vice-President, and President of the International Council of Scientific Unions.

After his retirement from EMBL, Kendrew became President of St John's College at the University of Oxford, a post he held from 1981 to 1987. In his will, he designated his bequest to St John's College for studentships in science and in music, for students from developing countries. The Kendrew Quadrangle at St John's College in Oxford, officially opened on 16 October 2010, is named after him.[12]

Kendrew was married to the former Elizabeth Jarvie (née Gorvin) from 1948 to 1956. Their marriage ended in divorce. Kendrew was subsequently partners with the artist Ruth Harris.[3] He had no surviving children.[13]

A biography of Kendrew, entitled A Place in History: The Biography of John C. Kendrew, by Paul M. Wassarman was published by Oxford University Press in 2020.

Selected publications

- Kendrew, JC (April 1949). "Foetal haemoglobin". Endeavour. 8 (30): 80–5. ISSN 0160-9327. PMID 18144277.

- Kendrew, JC; Parrish, RG; Marrack, JR; Orlans, ES (November 1954). "The species specificity of myoglobin". Nature. 174 (4438): 946–9. Bibcode:1954Natur.174..946K. doi:10.1038/174946a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 13214049. S2CID 4281674.

- Kendrew, JC; Parris, RG (January 1955). "Imidazole complexes of myoglobin and the position of the haem group". Nature. 175 (4448): 206–7. Bibcode:1955Natur.175..206K. doi:10.1038/175206b0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 13235845. S2CID 37160617.

- Ingram, DJ; Kendrew, JC (October 1956). "Orientation of the haem group in myoglobin and its relation to the polypeptide chain direction". Nature. 178 (4539): 905–6. Bibcode:1956Natur.178..905I. doi:10.1038/178905a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 13369569. S2CID 26921410.

- Kendrew, JC; Bodo, G; Dintzis, HM; Parrish, RG; Wyckoff, H; Phillips, DC (March 1958). "A three-dimensional model of the myoglobin molecule obtained by x-ray analysis". Nature. 181 (4610): 662–6. Bibcode:1958Natur.181..662K. doi:10.1038/181662a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 13517261. S2CID 4162786.

- Kendrew, JC (July 1959). "Structure and function in myoglobin and other proteins". Federation Proceedings. 18 (2, Part 1): 740–51. ISSN 0014-9446. PMID 13672267.

- Kendrew, JC; Watson, HC; Strandberg, BE; Dickerson, RE; Phillips, DC; Shore, VC (May 1961). "The amino-acid sequence x-ray methods, and its correlation with chemical data". Nature. 190 (4777): 666–70. Bibcode:1961Natur.190..666K. doi:10.1038/190666a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 13752474. S2CID 39469512.

- Watson, HC; Kendrew, JC (May 1961). "The amino-acid sequence of sperm whale myoglobin. Comparison between the amino-acid sequences of sperm whale myoglobin and of human hæmoglobin". Nature. 190 (4777): 670–2. Bibcode:1961Natur.190..670W. doi:10.1038/190670a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 13783432. S2CID 4170869.

- Kendrew, JC (December 1961). "The three-dimensional structure of a protein molecule". Scientific American. 205 (6): 96–110. Bibcode:1961SciAm.205f..96K. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1261-96. ISSN 0036-8733. PMID 14455128.

- Kendrew, JC (October 1962). "The structure of globular proteins". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 4 (2–4): 249–52. doi:10.1016/0010-406X(62)90009-9. ISSN 0010-406X. PMID 14031911.

- Kendrew, John C. (1966). The thread of life: an introduction to molecular biology. London: Bell & Hyman. ISBN 978-0-7135-0618-1.

References

- ^ Huxley, Hugh Esmor (1953). Investigations of biological structures by X-ray methods : the structure of muscle. lib.cam.ac.uk (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge. OCLC 885437514. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.604904. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ a b c "John Kendrew academic genealogy". academictree.org.

- ^ a b c Holmes, K. C. (2001). "Sir John Cowdery Kendrew. 24 March 1917 - 23 August 1997: Elected F.R.S. 1960". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 47: 311–332. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2001.0018. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0028-EC77-7. PMID 15124647.

- ^ "Clifton College Register" Muirhead, J.A.O. p462: Bristol; J.W Arrowsmith for Old Cliftonian Society; April, 1948

- ^ "No. 35301". The London Gazette. 7 October 1941. p. 5793.

- ^ "No. 36633". The London Gazette (Supplement). 28 July 1944. p. 3562.

- ^ "No. 37168". The London Gazette (Supplement). 6 July 1945. p. 3552.

- ^ Kendrew, John Cowdery (1949). X-ray studies of certain crystalline proteins : the crystal structure of foetal and adult sheep haemoglobins and of horse myoglobin. lib.cam.ac.uk (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.648050. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ "John C. Kendrew Biographical".

- ^ a b Stoddart, Charlotte (1 March 2022). "Structural biology: How proteins got their close-up". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-022822-1. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ Kendrew, JC; Dickerson, RE; Strandberg, BE; et al. (February 1960). "Structure of myoglobin: A three-dimensional Fourier synthesis at 2 A. resolution". Nature. 185 (4711): 422–7. Bibcode:1960Natur.185..422K. doi:10.1038/185422a0. PMID 18990802. S2CID 4167651.

- ^ "The 21st Century: Kendrew Quadrangle". St John's College, Oxford. 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ Wolfgang Saxon (30 August 1997). "John C. Kendrew Dies at 80; Biochemist Won Nobel in '62". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

Further reading

- John Finch; 'A Nobel Fellow on Every Floor', Medical Research Council 2008, 381 pp, ISBN 978-1-84046-940-0; this book is all about the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge.

- Oxford University Press, page on Paul M. Wassarman, A Place in History, ISBN 9780199732043, 2020

External links

- John C. Kendrew on Nobelprize.org

- Portraits of John Kendrew at the National Portrait Gallery, London