Juan Gris

Juan Gris | |

|---|---|

Gris in 1922 (photograph by Man Ray) | |

| Born | José Victoriano González-Pérez 23 March 1887 Madrid, Spain |

| Died | 11 May 1927 (aged 40) Boulogne-sur-Seine, Paris, France |

| Known for | Painting, drawing |

| Movement | Cubism |

| Spouse | Lucie Belin |

José Victoriano González-Pérez (23 March 1887 – 11 May 1927),[1] better known as Juan Gris (Spanish: [ˈxwaŋ ˈɡɾis]; French: [gʀi]), was a Spanish painter born in Madrid who lived and worked in France for most of his active period. Closely connected to the innovative artistic genre Cubism, his works are among the movement's most distinctive.

Life

Gris was born in Madrid and later studied engineering at the Madrid School of Arts and Sciences. There, from 1902 to 1904, he contributed drawings to local periodicals. From 1904 to 1905, he studied painting with the academic artist José Moreno Carbonero. It was in 1905 that José Victoriano González adopted the more distinctive name Juan Gris.[2]

In 1909, Lucie Belin (1891–1942)—Gris' wife—gave birth to Georges Gonzalez-Gris (1909–2003), the artist's only child. The three lived at the Bateau-Lavoir, 13 Rue Ravignan, Paris, from 1909 to 1911. In 1912 Gris met Charlotte Augusta Fernande Herpin (1894–1983), also known as Josette. Late 1913 or early 1914 they lived together at the Bateau-Lavoir until 1922. Josette Gris was Juan Gris' second companion and unofficial wife.[3][4]

Career

In 1906, after he sold all his possessions,[5] he moved to Paris and became friends with the poets Guillaume Apollinaire, Max Jacob, and artists Henri Matisse, Georges Braque, Fernand Léger and Jean Metzinger.[6][7] He submitted darkly humorous illustrations to journals such as the anarchist satirical magazine L'Assiette au Beurre, and also Le Rire, Le Charivari, and Le Cri de Paris.[8] In Paris, Gris followed the lead of Metzinger and another friend and fellow countryman, Pablo Picasso.

Gris began to paint seriously in 1911 (when he gave up working as a satirical cartoonist), developing at this time a personal Cubist style.[9] In A Life of Picasso, John Richardson writes that Jean Metzinger's 1911 work, Le goûter (Tea Time), persuaded Juan Gris of the importance of mathematics in painting.[10] Gris exhibited for the first time at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants (a painting entitled Hommage à Pablo Picasso).[9]

"He appears with two styles", writes art historian Peter Brooke, "In one of them a grid structure appears that is clearly reminiscent of the Goûter and of Metzinger's later work in 1912."[9] In the other, Brooke continues, "the grid is still present but the lines are not stated and their continuity is broken. Their presence is suggested by the heavy, often triangular, shading of the angles between them... Both styles are distinguished from the work of Picasso and Braque by their clear, rational and measurable quality."[9] Although Gris regarded Picasso as a teacher, Gertrude Stein wrote in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas that "Juan Gris was the only person whom Picasso wished away".[11]

In 1912, Gris exhibited at the Exposició d'art cubista, Galeries Dalmau in Barcelona, the first declared group exhibition of Cubism worldwide;[12][13] the gallery Der Sturm in Berlin; the Salon de la Société Normande de Peinture Moderne in Rouen; and the Salon de la Section d'Or in Paris. Gris, in that same year, signed a contract that gave Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler exclusive rights to his work.[14]

At first Gris painted in the style of Analytical Cubism, a term he himself later coined,[15] but after 1913 he began his conversion to Synthetic Cubism, of which he became a steadfast interpreter, with extensive use of papier collé or, collage. Unlike Picasso and Braque, whose Cubist works were practically monochromatic, Gris painted with bright harmonious colors in daring, novel combinations in the manner of his friend Matisse. Gris exhibited with the painters of the Puteaux Group in the Salon de la Section d'Or in 1912.[16] His preference for clarity and order influenced the Purist style of Amédée Ozenfant and Charles Edouard Jeanneret (Le Corbusier), and made Gris an important exemplar of the post-war "return to order" movement.[17] In 1915 he was painted by his friend, Amedeo Modigliani. In November 1917 he made one of his few sculptures, the polychrome plaster Harlequin.[18][19]

Crystal Cubism

Gris's works from late 1916 through 1917 exhibit a greater simplification of geometric structure, a blurring of the distinction between objects and setting, between subject matter and background. The oblique overlapping planar constructions, tending away from equilibrium, can best be seen in Woman with Mandolin, after Corot (September 1916) and in its epilogue, Portrait of Josette Gris (October 1916; Museo Reina Sofia).[20]

The clear-cut underlying geometric framework of these works seemingly controls the finer elements of the compositions; the constituent components, including the small planes of the faces, become part of the unified whole. Though Gris certainly had planned the representation of his chosen subject matter, the abstract armature serves as the starting point.[20]

The geometric structure of Juan Gris's Crystal period is already palpable in Still Life before an Open Window, Place Ravignan (June 1915; Philadelphia Museum of Art). The overlapping elemental planar structure of the composition serves as a foundation to flatten the individual elements onto a unifying surface, foretelling the shape of things to come.

In 1919 and particularly 1920, artists and critics began to write conspicuously about this 'synthetic' approach, and to assert its importance in the overall scheme of advanced Cubism.[20]

Designer and theorist

In 1924, he designed ballet sets and costumes for Sergei Diaghilev and the famous Ballets Russes.[21]

Gris articulated most of his aesthetic theories during 1924 and 1925. He delivered his definitive lecture, Des possibilités de la peinture, at the Sorbonne in 1924.[6] Major Gris exhibitions took place at the Galerie Simon in Paris and the Galerie Flechtheim in Berlin in 1923 and at the Galerie Flechtheim in Düsseldorf in 1925.[22]

Death

After October 1925, Gris was frequently ill with bouts of uremia and cardiac problems. He died of kidney failure[23] in Boulogne-sur-Seine (Paris) on 11 May 1927, at the age of 40, leaving a wife, Josette, and a son, Georges.

Art market

The top auction price for a Gris work is $57.1 million (£34.8 million), achieved for his 1915 painting Nature morte à la nappe à carreaux (Still Life with Checked Tablecloth).[24] This surpassed previous records of $20.8 million for his 1915 still life Livre, pipe et verres, $28.6 million for the 1913 artwork Violon et guitare [25] and $31.8 million for The musician's table, now in the Met.[26]

Selected works

- Violin Hanging on a Wall (Le violon accroché), (1913). Guggenheim Museum, New York[27]

- Pears and Grapes on a Table, (autumn 1913). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.[28][29]

- Bottle of Rum and Newspaper (Bouteille de rhum et journal), (June 1914). Guggenheim Museum, New York[27]

- Cherries (Les cerises), (1915). Guggenheim Museum, New York[27]

- Fruit Dish on a Checkered Tablecloth (Compotier et nappe à carreaux), (November 1917). Guggenheim Museum, New York[27]

Gallery

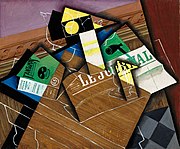

-

Maisons à Paris (Houses in Paris), 1911, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

-

Juan Legua, 1911, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

-

Guitar and Pipe, 1913, Dallas Museum of Art, Texas

-

Glass of Beer and Playing Cards, 1913, Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio

-

Violin and Checkerboard, 1913, Private collection

-

The Bottle of Anís del Mono, 1914, Queen Sofia Museum, Madrid

-

Fantômas, 1915, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

-

The Breakfast, 1915, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris

-

Newspaper and Fruit Dish, 1916, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT

-

Glass and Checkerboard, c. 1917, National Gallery of Art

-

Compotier et nappe à carreaux, 1917, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

-

The Guitar (La Guitarra), 1918, Fundación Telefónica at Queen Sofia Museum, Madrid

-

Still Life with Fruit Dish and Mandolin, 1919, Private collection, Paris

-

Harlequin with Guitar, 1919, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

-

Le Canigou, 1921, Albright–Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

-

The blue carpet, 1925, Centre national d'art et de culture Georges-Pompidou, Paris

-

The Painter's Window, 1925, Baltimore Museum of Art, Maryland

Tribute

On 23 March 2012, Google celebrated Juan Gris’ 125th Birthday with a doodle.[30][31]

Notes

- ^ Jiménez-Blanco, María Dolores. "José Victoriano González Pérez". Diccionario biográfico España (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia.

- ^ Gris 1998, p. 124.

- ^ Geoffrey David Schwartz, The Cubist's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, December 1914

- ^ Christopher Green, et al, Juan Gris: Whitechapel Art Gallery, London [18 September - 29 November 1992; Staatsgalerie Stuttgart 18 December 1992-14 February 1993; Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo 6 March - 2 May 1993, Yale University Press, 1992, p. 302, ISBN 0300053746

- ^ "Juan Gris". Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ a b Handbook, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, University of California, 1983, p. 26, 83

- ^ Metzinger, Jean, Le Cubisme était né, Souvenirs, Chambéry, Editions Présence, 1972, p. 48

- ^ Print Review, Issues 18–20, Pratt Graphics Center, Kennedy Galleries, University of Michigan, 1984, p. 69

- ^ a b c d "Peter Brooke, On "Cubism" in context, online since 2012". Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ John Richardson: A Life of Picasso, volume II, 1907–1917, The Painter of Modern Life, Jonathan Cape, London, 1996, p. 211.

- ^ After Gris' death, Stein said to Picasso, "You never realized his meaning because you did not have it", to which Picasso replied, "You know very well that I did". Caws, Mary Ann (2005). Pablo Picasso. Reaktion Books. ISBN 1-86189-247-0. p. 66.

- ^ Mark Antliff and Patricia Leighten, A Cubism Reader, Documents and Criticism, 1906-1914, University of Chicago Press, 2008, pp. 293–295

- ^ Commemoració del centenari del cubisme a Barcelona. 1912-2012, Associació Catalana de Crítics d'Art – ACCA

- ^ Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Lucy Flint-Gohlke, Thomas M. Messer, Handbook, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Abrams, 1983. 1983. ISBN 9780892070381. Retrieved 19 September 2014 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Honour, H. and J. Fleming, (2009) A World History of Art. 7th edn. London: Laurence King Publishing, p. 784. ISBN 9781856695848

- ^ Cooper, Philip. Cubism. London: Phaidon, 1995, p. 56. ISBN 0714832502

- ^ Cowling and Mundy 1990, p. 117.

- ^ Gris 1998, p. 136.

- ^ "Sculpture". frenchsculpture.org. 19 February 2014. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Christopher Green, Cubism and its Enemies, Modern Movements and Reaction in French Art, 1916–1928, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1987, pp. 13–47.

- ^ Robert Craig Hansen, Scenic and costume design for the Ballets Russes, Issue 30 of Theater and dramatic studies, UMI Research Press, 1 August 1985, p. 86, ISBN 0835716813

- ^ José Pierre, Cubism, Heron, 1969, p. 135

- ^ Green, Oxford Art Online: "Juan Gris"

- ^ "Juan Gris (1887–1927) | Nature morte à la nappe à carreaux | Impressionist & Modern Art Auction | Christie's". Christies.com.cn. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ "Juan Gris (1887–1927) | Impressionist & Modern Art Auction | Christie's". Christies.com.cn. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ "Acquisitions of the month: August-September 2018". Apollo Magazine. 3 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York".

- ^ Juan Gris, Pears and Grapes on a Table, autumn 1913. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Retrieved 5 April 2019

- ^ Juan Gris. Pears and grapes on a table (or Still life with pears), (1913). (Artwork in exhibitions information since 1947). artdesigncafe. Retrieved 5 April 2019

- ^ Desk, OV Digital (23 March 2023). "23 March: Remembering Juan Gris on Birthday". Observer Voice. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

{cite web}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Juan Gris' 125th Birthday". www.google.com. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

References

- Cowling, Elizabeth; Mundy, Jennifer. 1990. On Classic Ground: Picasso, Léger, de Chirico and the New Classicism 1910–1930. London: Tate Gallery. ISBN 1-85437-043-X

- Green, Christopher. "Gris, Juan." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web.

- Gris, Juan. 1998. Juan Gris: peintures et dessins, 1887–1927. [Marseille]: Musées de Marseille. ISBN 2-7118-2969-3. (French language)

- Santarelli, Cristina (2020). "Realism and Idealism in Juan Gris's Still Lifes with Musical Instruments". Music in Art: International Journal for Music Iconography. 45 (1–2): 217–229. ISSN 1522-7464.

External links

- Juan Gris, Joconde, Portail des collections des musées de France

- Juan Gris, Culture.gouv.fr, le site du Ministère de la culture – base Mémoire

- Artcyclopedia – Links to Gris' works

- The Athenaeum Archived 21 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine – Extensive list and images of Gris' works

- Juan Gris in Artfacts.Net Archived 7 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine See actual exhibitions and related galleries and museums for Juan Gris

- Juan Gris in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website

- Juan Gris Estudios de obra temprana y catálogo de pinturas, LyP.