Communist_Party_of_Bohemia_and_Moravia

Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia Komunistická strana Čech a Moravy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | KSČM |

| Chairwoman | Kateřina Konečná |

| First Vice-Chairman | Petr Šimůnek |

| Deputy Leaders | Marie Pěnčíková Leo Luzar Milan Krajča |

| Founded | 31 March 1990 |

| Preceded by | Communist Party of Czechoslovakia |

| Headquarters | Politických vězňů 9, Prague |

| Newspaper | Haló noviny |

| Think tank | Institute of the Czech Left |

| Youth wing | Young Communists |

| Membership (2023) | 18,307 |

| Ideology | Communism[1] Marxism Socialism Euroscepticism |

| Political position | Left-wing to far-left |

| National affiliation | Stačilo! (Since 2023) Left Bloc (1992–1994) Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (1990–1992) |

| European affiliation | Party of the European Left (observer) |

| European Parliament group | The Left in the European Parliament – GUE/NGL (2004–2024) Non-Inscrits (2024–)[2] |

| International affiliation | IMCWP WAP[3](disputed) |

| Colours | Red |

| Slogan | "S lidmi pro lidi!" "With the people for the people!" |

| Chamber of Deputies | 0 / 200 |

| Senate | 0 / 81 |

| European Parliament | 1 / 21 |

| Regional councils | 32 / 675 |

| Local councils | 466 / 62,300 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| www | |

| Part of a series on |

| Communist parties |

|---|

|

|---|

|

|

The Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (Czech: Komunistická strana Čech a Moravy, KSČM) is a communist party[4] in the Czech Republic.[5] As of 2022, KSČM has a membership of 20,450.[6] Sources variously describe the party as either left-wing[7][8] or far-left[9][10] on the political spectrum. It is one of the few former ruling parties in post-Communist Central Eastern Europe to have not dropped the Communist title from its name, although it has changed its party program to adhere to laws adopted after 1989.[11][12] It was previously a member party of The Left in the European Parliament – GUE/NGL in the European Parliament,[13] and an observer member of the European Left Party,[14] but is now unaffiliated.

For most of the first two decades after the Velvet Revolution, the party was politically isolated and accused of extremism, but later moved closer to the Czech Social Democratic Party (ČSSD).[12] After the 2012 Czech regional elections, KSČM began governing in coalition with the ČSSD in 10 regions.[15] It has never been part of a governing coalition in the executive branch but provided parliamentary support to Andrej Babiš' Second Cabinet until April 2021. The party's youth organization was banned from 2006 to 2010,[12][16] and there have been calls from other parties to outlaw the main party.[17] Until 2013, it was the only political party in the Czech Republic printing its own newspaper, called Haló noviny.[18] The party's two cherry logo comes from the song Le Temps des cerises, a revolutionary song associated with the Paris Commune.[19]

History

The party was formed in 1989 by a congress of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ), which decided to create a party for the territories of Bohemia and Moravia (including Czech Silesia), the areas that were to become the Czech Republic. The new party's organization was significantly more democratic and decentralized than the previous party, and gave local district branches of the party significant autonomy.[20]

In 1990, KSČ was reorganized as a federation of KSČM and the Communist Party of Slovakia (KSS). Later, KSS changed its name to the Party of the Democratic Left, and the federation dissolved in 1992. During the party's first congress, held in Olomouc in October 1990, party leader Jiří Svoboda attempted to reform the party into a democratic socialist one, proposing a democratic socialist program and changing the name to the transitional Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia: Party of Democratic Socialism.[21] Svoboda had to balance the criticisms of older, conservative communists, who made up a majority of the party's members, with the demands of an increasingly large and moderate bloc of members, led primarily by a group of young KSČM parliamentarians called the Democratic Left, who demanded the immediate social democratization of the party. Delegates approved the new program but rejected the name change.[11]

During 1991 and 1992, factional tensions increased, with the party's conservative, anti-revisionist wing increasingly vocal in criticizing Svoboda. There was an increase in popularity of the anti-revisionist Marxist–Leninist clubs amongst rank-and-file party members. On the party's other wing, the Democratic Left became increasingly critical of the slow pace of the reforms and began demanding a referendum of members to change the name. In December 1991, the Democratic Left split off and formed the short-lived Party of Democratic Labour. The referendum on changing the name was held in 1992, with 75.94% voting not to change the name.[11]

The party's second congress, held in Kladno in December 1992, showed the increasing popularity of the party's anti-revisionist wing. It passed resolutions reinterpreting the 1990 program as a "starting point" for KSČM, rather than a definitive statement of a post-communist program. Svoboda, who was hospitalized due to an attack by an anti-communist, could not attend the congress but was nevertheless overwhelmingly re-elected.[11] After the party's second congress in 1992, several groups split away. A group of post-communist delegates split off and merged with the Party of Democratic Labour to form the Party of the Democratic Left (SDL). Several independent left-wing members who had participated with KSČM in the 1992 electoral pact, which was called the Left Bloc, left the party to form the Left Bloc Party.[20] Both groups eventually merged into the Party of Democratic Socialism.[22]

In 1993, Svoboda attempted to expel the members of the "For Socialism" platform, a group in the party that wanted a restoration of the pre-1989 Communist regime;[23] however, with only the lukewarm support of KSČM's central committee, he briefly resigned. He withdrew his resignation after the central committee agreed to move the party's next congress forward to June 1993 to resolve the issues of its name and ideology.[20] At the 1993 congress, held in Prostějov, Svoboda's proposals were overwhelmingly rejected by two-thirds majorities. Svoboda did not seek re-election as chairman, and neocommunist Miroslav Grebeníček was elected chairman. Grebeníček and his supporters were critical of what they termed the inadequacies of the pre-1989 regime but supported the retention of the party's communist character and program. The members of the "For Socialism" platform were expelled at the congress, with the existence of platforms in the party being banned altogether, on the grounds that they gave too much influence to minority groups. Svoboda left the party.[20]

The expelled members of "For Socialism" formed the Party of Czechoslovak Communists, later renamed the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, which was led by Miroslav Štěpán.[22] KSČM refuses to work with this group. The party was left on the sidelines for most of the first decade of the Czech Republic's existence. Václav Havel suspected KSČM was still an unreconstructed neo-Stalinist party and prevented it from having any influence during his presidency; however, the party provided the one-vote margin that elected Havel's successor Václav Klaus as president.[24] After a long-running battle with the Ministry of the Interior, the Communist Youth Union led by Milan Krajča, was dissolved in 2006 for allegedly endorsing in its program the replacement of private with collective ownership of the means of production.[16] The decision met with international protests.[25]

In November 2008, the Czech Senate asked the Supreme Administrative Court to dissolve KSČM because of its political program, which the Senate argued contradicted the Constitution of the Czech Republic. 30 out of the 38 senators who were present agreed to this request, and expressed the view that the party's program did not reject violence as a means of attaining power and adopted The Communist Manifesto of Karl Marx;[26] however, this was only a symbolic gesture, as according to the constitution only the cabinet may file a petition to the Supreme Administrative Court to dissolve a political party. For the first two decades after the end of Communist rule in Czechoslovakia, the party was politically isolated. After the 2012 Czech regional elections, it started participating in coalitions with the Czech Social Democratic Party, forming part of the ruling coalition in 10 out of 13 regions.[15] From 2018 to 2021, KSČM provided parliamentary support to Andrej Babiš' Second Cabinet.[27][28]

After the party's poor performance in the 2021 Czech legislative election, in which KSČM failed to reach the 5% voting threshold and was excluded from representation in parliament for the first time in its history, Filip resigned as leader of the party.[29] On 23 October 2021, Member of European Parliament Kateřina Konečná was elected as leader.[30]

Ideology

As a communist party and the successor of the former ruling Communist Party of Czechoslovakia,[4] its party platform promotes anti-capitalism[31] and socialism[32] through a Marxist lens.[33] It holds Eurosceptic views in regards to the European Union.[34][35][36]

Leaders

| # | Name (Born–Died) |

Portrait | Term of Office | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jiří Machalík (1945–2014) |

|

31 March 1990 | 13 October 1990 |

| 2 | Jiří Svoboda (b. 1945) |

|

13 October 1990 | 25 June 1993 |

| 3 | Miroslav Grebeníček (b. 1947) |

|

25 June 1993 | 1 October 2005 |

| 4 | Vojtěch Filip (b. 1955) |

|

1 October 2005 | 9 October 2021 |

| 5 | Kateřina Konečná (b. 1981) |

|

23 October 2021 | present |

Electoral results

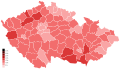

KSČM's strongest bases of support are in the regions hit by deindustrialization,[citation needed] particularly in the Karlovy Vary and Ústí nad Labem regions. In 2012, the party won a regional election for the first time in Ústí nad Labem. Its regional leader Oldřich Bubeníček subsequently became the first communist regional governor in the history of Czech Republic.[37][better source needed] The party is stronger among older than younger voters, with the majority of its membership over 60.[38] The party is also stronger in small and medium-sized towns than in big cities.[39]

Parliament

Chamber of Deputies

| Chamber of Deputies of the Parliament of the Czech Republic | |||||||

| Year | Leader | Votes | % | Seats | ± | Place | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | Jiří Machalík | 954,690 | 13.2 | 33 / 200

|

New | 2nd | Opposition |

| 1992 | Jiří Svoboda | 909,490 | 14.0[a] | 35 / 200

|

2nd | Opposition | |

| 1996 | Miroslav Grebeníček | 626,136 | 10.3 | 22 / 200

|

3rd | Opposition | |

| 1998 | Miroslav Grebeníček | 658,550 | 11.0 | 24 / 200

|

3rd | Opposition | |

| 2002 | Miroslav Grebeníček | 882,653 | 18.5 | 41 / 200

|

3rd | Opposition | |

| 2006 | Vojtěch Filip | 685,328 | 12.8 | 26 / 200

|

3rd | Opposition | |

| 2010 | Vojtěch Filip | 589,765 | 11.3 | 26 / 200

|

4th | Opposition | |

| 2013 | Vojtěch Filip | 741,044 | 14.9 | 33 / 200

|

3rd | Opposition | |

| 2017 | Vojtěch Filip | 393,100 | 7.8 | 15 / 200

|

5th | Confidence and supply | |

| 2021 | Vojtěch Filip | 193,817 | 3.6 | 0 / 200

|

7th | No seats | |

- Notes

-

KSCM 1996

-

KSCM 1998

-

KSCM 2002

-

KSCM 2006

-

KSCM 2010

-

KSCM 2013

-

KSCM 2017

-

KSCM 2021

Senate

| Senate of the Parliament of the Czech Republic | |||||||

| Year | First round | Second round | No. of seats won | No. of overall seats won |

± | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | ||||

| 1996 | 393,494 | 14.3 | 45,304 | 2.0 | 2 / 81

|

2 / 81

|

New |

| 1998 | 159,123 | 16.5 | 31,097 | 5.8 | 2 / 27

|

4 / 81

|

|

| 2000 | 152,934 | 17.8 | 73,372 | 13.0 | 0 / 27

|

3 / 81

|

|

| 2002 | 110,171 | 16.5 | 57,434 | 7.0 | 1 / 27

|

3 / 81

|

|

| 2004 | 125,892 | 17.4 | 65,136 | 13.6 | 1 / 27

|

2 / 81

|

|

| 2006 | 134,863 | 12.7 | 26,001 | 4.5 | 0 / 27

|

2 / 81

|

|

| 2008 | 147,186 | 14.1 | did not make it | did not make it | 1 / 27

|

3 / 81

|

|

| 2010 | 117,374 | 10.2 | did not make it | did not make it | 0 / 27

|

2 / 81

|

|

| 2012 | 153,335 | 17.4 | 79,663 | 15.5 | 1 / 27

|

2 / 81

|

|

| 2014 | 99,973 | 9.74 | did not make it | did not make it | 0 / 27

|

1 / 81

|

|

| 2016 | 83,741 | 9.50 | 5,737 | 1.35 | 0 / 27

|

1 / 81

|

|

| 2018 | 80,371 | 7.38 | 3,578 | 0.86 | 0 / 27

|

0 / 81

|

|

| 2020 | 40,994 | 4.11 | did not make it | did not make it | 0 / 27

|

0 / 81

|

|

| 2022 | 17,612 | 1.60 | did not make it | did not make it | 0 / 27

|

0 / 81

|

|

| 2024 | 14,321 | 1.80 | did not make it | did not make it | 0 / 27

|

0 / 81

|

|

European Parliament

| Election | List leader | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | EP Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Miloslav Ransdorf | 472,862 | 20.27 (#2) | 6 / 24

|

New | GUE/NGL |

| 2009 | 334,577 | 14.18 (#3) | 4 / 22

|

|||

| 2014 | Kateřina Konečná | 166,478 | 10.99 (#4) | 3 / 21

|

||

| 2019 | 164,624 | 6.94 (#7) | 1 / 21

|

The Left | ||

| 2024[a] | 283,935 | 9.56 (#4) | 1 / 21

|

NI |

Local councils

| Year | Votes | % | Seats |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 17,413,545 | 13.6 | 5,837 / 62,160

|

| 1998 | 10,703,975 | 13.7 | 5,748 / 62,920

|

| 2002 | 11 696 976 | 14.5 | 5,702 / 62,494

|

| 2006 | 11,730,243 | 10.8 | 4,268 / 62,426

|

| 2010 | 8,628,685 | 9.6 | 3,189 / 62,178

|

| 2014 | 7,730,503 | 7.8 | 2,510 / 62,300

|

| 2018 | 5,416,907 | 4.9 | 1,426 / 62,300

|

| 2022 | 466 / 62,300

|

Regional councils

| Year | Votes | % | Seats | ± | Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 496,688 | 21.1 | 161 / 675

|

New | 3rd |

| 2004 | 416,807 |

19.7 |

157 / 675

|

2nd | |

| 2008 | 438,024 |

15.0 |

114 / 675

|

3rd | |

| 2012 | 538,953 |

20.4 |

182 / 675

|

2nd | |

| 2016 | 267,047 |

10.6 |

86 / 675

|

3rd | |

| 2020 | 131,770 |

4.8 |

13 / 675

|

9th |

References

- ^ Bozóki, A & Ishiyama, J (2002) The Communist Successor Parties of Central and Eastern Europe, pp150-153

- ^ "STAČILO! a frakce aneb program za koryta nevyměníme!". KSČM. 9 July 2024. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ "Milan Krajča, Vice-President of the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia(Czech Republic)". World Anti-Imperialist Platform. 17 May 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ a b Bozóki & Ishiyama 2002, pp. 150–153.

- ^ Nordsieck, Wolfram (October 2021). "Czechia". Parties and Elections in Europe. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ "Stranám ubývají členové. Rozrůstají se jen SPD a STAN". ČT24. 18 March 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ Seelinger, Lani (11 July 2014). "Why the Czech Communists are here to stay". visegradrevue.eu. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- ^ Pink, Michal (August 2012). "The Electoral Base of Left-Wing Post-Communist Political Parties in the Former Czechoslovakia". Central European Political Studies Review. 14 (2–3): 170–192. Retrieved 12 August 2019..

- ^ Kapsas, André (6 April 2018). "Andrej Babiš et les sociaux-démocrates tchèques négocient leur alliance". Courrier d'Europe centrale (in French). Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- ^ Lopatka, Jan (30 April 2018). "New dawn or swan song? Czech communists eye slice of power after decades". Reuters. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Bozóki & Ishiyama 2002, p. 146.

- ^ a b c "Elections: What's on the menu". Prague Daily Monitor. 25 October 2013. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ "European United Left & Nordic Green Left European Parliamentary Group delegations". Guengl.eu. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ "Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia". european-left.org. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ a b "ČSSD to rule along with Communists in 10 of 13 Czech regions". Prague Monitor. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Communists denounce ban on far-left youth movement". Radio Praha. 19 October 2006. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ "Czech Activists Seek to Outlaw Communist Party". The New York Times. 23 December 2009. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ "Halonoviny.cz - české levicové zprávy". Archived from the original on 16 November 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ "Kdo jsme". Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia. Archived from the original on 14 November 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d Bozóki & Ishiyama 2002, p. 147.

- ^ Bozóki & Ishiyama 2002, pp. 145–146.

- ^ a b Bozóki & Ishiyama 2002, p. 157.

- ^ Bozóki & Ishiyama 2002, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Thompson, Wayne C. (2008). The World Today Series: Nordic, Central and Southeastern Europe 2008. Harpers Ferry, West Virginia: Stryker-Post Publications. ISBN 978-1-887985-95-6.

- ^ "Czech Communist Youth Union outlawed". The Guardian. Communist Party of Australia. 25 October 2006. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ "Komunisté ve světě nás nedají, říká o hrozbě rozpuštění šéf KSČM". iDnes, the online portal of Mladá fronta DNES. Czech News Agency. November 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ^ "ČSSD v referendu schválila vládu s ANO. Babiš však ještě nemá vyhráno". iDNES.cz. 15 June 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ "Babiš je podruhé premiérem. Hájil, že vláda bude opřená o komunisty". iDNES.cz. 6 June 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ "Vedení KSČM rezignovalo. Vstanou noví bojovníci, vzkázal Filip". iDNES.cz (in Czech). 9 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ "Novou šéfkou KSČM se stala Konečná. Vyhrála s velkou převahou". Novinky.cz (in Czech). 23 October 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ "Musíme vést třídní boj a zničit kapitalismus, řekla v Rozstřelu Konečná z KSČM". Idnes.cz. 24 April 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "Kdo jsme". KSČM. Archived from the original on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "Naděje pro Českou republiku (2006)" (PDF). KSČM (in Czech). 29 March 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ "How Europe will break on Brexit". Politico.eu. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ "O Brexitu neboli proč by EU měla jít". KSČM. 19 July 2016. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ "Krachující Evropská unie a Česká republika". KSČM. 9 September 2016. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ "Oldřich Bubeníček". Novinky.cz. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ Bozóki & Ishiyama 2002, p. 155.

- ^ Bozóki & Ishiyama 2002, p. 156.

Bibliography

- Bozóki, András; Ishiyama, John (2002). The Communist Successor Parties of Central and Eastern Europe. Routledge. ISBN 9780765609861.

Further reading

- Hough, Dan; Paterson, William E.; Sloam, James, eds. (2005). Learning from the West? Policy Transfer and Programmatic Change in the Communist Successor Parties of East Central Europe. Routledge. ISBN 9780415373166.