Kamerun campaign

| Kamerun campaign | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the African theatre of World War I | |||||||||

British QF 12-pounder 8 cwt firing at Fort Dachang in 1915 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

British: 1,668–7,000[2] French: 7,000 Belgian: 600–3,000[3][4] Total: 9,000 |

1914: 1,855 1915: 6,000[5] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

British: 917–1,668[6] French: 906–2,567[7][8] | 5,000[9] | ||||||||

| hundreds to thousands of Duala civilians killed[10] | |||||||||

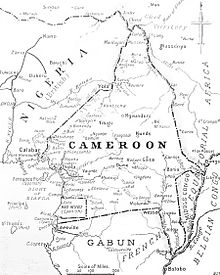

The Kamerun campaign took place in the German colony of Kamerun in the African theatre of the First World War when the British, French and Belgians invaded the German colony from August 1914 to March 1916. Most of the campaign took place in Kamerun but skirmishes also broke out in British Nigeria. By the Spring of 1916, following Allied victories, the majority of German troops and the civil administration fled to the neighbouring neutral colony of Spanish Guinea (Río Muni). The campaign ended in a defeat for Germany and the partition of its former colony between France and Britain.

Background

Germany had established a protectorate over Kamerun by 1884 during the Scramble for Africa, and expanded its control in the Bafut Wars and Adamawa Wars. In 1911, France ceded Neukamerun (New Cameroon), a large territory to the east of Kamerun, to Germany as a part of the Treaty of Fez, the settlement that ended the Agadir Crisis. In 1914, the German colony of Kamerun made up all of modern Cameroon as well as portions of Nigeria, Chad, Gabon, the Republic of the Congo and the Central African Republic. Kamerun was surrounded on all sides by Entente territory. British-held Nigeria was to the north-west. The Belgian Congo bordered the colony to the south-east and French Equatorial Africa lay in the east. The neutral colony of Spanish Guinea was bordered by German Kamerun on all sides but one, which faced the sea. In 1914, on the eve of World War I, Kamerun remained largely unexplored and unmapped by European invaders.[11] In 1911–1912 the border with the French colonies of Gabon, Middle Congo, Ubangi-Shari and Chad was established and in 1913 the border between the colonies of Nigeria and Kamerun was defined.[12]

The German military forces stationed in the colony at the time consisted of around 1,855 Schutztruppen (protection troops). However, after the outbreak of war by mid-1915, the Germans were able to recruit an army of around 6,000. Allied forces on the other hand in the territories surrounding Kamerun were much larger. French Equatorial Africa alone could mobilize as many as 20,000 soldiers on the eve of war while British Nigeria to the west could raise an army of 7,550.[5]

Operations

Invasion in 1914

At the outbreak of war in Europe in early August 1914, the German colonial administration in Kamerun attempted to offer neutrality with Britain and France in accordance with Articles 10 and 11 of the Berlin Act of 1885.[13] However this was rejected by the Allies. The French were eager to regain the land ceded to Germany in the Treaty of Fez in 1911. The first Allied expeditions into the colony on 6 August 1914 were from the east conducted by French troops from French Equatorial Africa under General Joseph Gaudérique Aymerich. This region was mostly marshland, undeveloped, and was initially not heavily contested by Germans.[14]

By 25 August 1914, British forces in present-day Nigeria had moved into Kamerun from three different points. They pushed into the colony towards Mara in the far north, towards Garua in the centre, and towards Nsanakang in the south. British forces moving towards Garua under the command of Colonel MacLear were ordered to push to the German border post at Tepe near Garua. The first engagement between British and German troops in the campaign took place at the Battle of Tepe, eventually resulting in German withdrawal.[15]

In the far north British forces attempted to take the German fort at Mora but initially failed. This resulted in a long siege of German positions which would last until the end of the campaign.[16] British forces in the south attacking Nsanakang were defeated and almost completely destroyed by German counter-attacks at the Battle of Nsanakong.[17] MacLear then pushed his forces further inland towards the German stronghold of Garua but was repulsed in the First Battle of Garua on 31 August.[18]

Naval operations

In September 1914, the Germans had mined the Kamerun or Wouri estuary and scuttled naval vessels there to protect Douala, the colony's largest city and commercial centre. British and French naval vessels bombarded towns on the coast and by late September had cleared mines and conducted amphibious landings in order to isolate Douala. On 27 September, the city surrendered to Brigadier General Charles Macpherson Dobell, commander of the combined Allied force. The occupation of the entire coast soon followed as the French captured more of the territories to the south-east in an amphibious operation at the Battle of Ukoko.[19]

War in 1915

By 1915, the majority of German forces, except for those holding out at the strongholds of Mora and Garua had withdrawn to the mountainous interior of the colony surrounding the new capital at Jaunde. In the spring of that year German forces were still able to significantly stall or repulse assaults by Allied forces. A German force under the command of Captain von Crailsheim from Garua even went on the offensive, engaging the British during a failed raid into Nigeria at the Battle of Gurin.[20] This surprisingly daring incursion into British territory prompted General Frederick Hugh Cunliffe to launch another attempt at taking the German fortresses at Garua at the Second Battle of Garua in June, resulting in a British victory.[21] This action freed Allied units in northern Kamerun to push further into the interior of the colony. This push resulted in the Allied victory at the Battle of Ngaundere on 29 June. Cunliffe's advance south to Jaunde, however, was stalled by heavy rains, and his force instead participated in the continuing Siege of Mora.[22]

When the weather improved, British forces under Cunliffe moved further south, capturing a German fort at the Battle of Banjo in November and occupying a number of other towns by the end of the year.[23] By December, the forces of Cunliffe and Dobell were in contact and ready to conduct an assault of Jaunde.[24] In this year most of Neukamerun was occupied by Belgian and French troops, who also began to prepare for an assault on Jaunde.[25]

Surrender in 1916

In early 1916, the German commander, Carl Zimmermann came to the conclusion that the campaign was lost. With Allied forces pressing in on Jaunde from all sides and German resistance faltering, he ordered all remaining German units and civilians to escape to the neutral Spanish colony of Rio Muni.[26] By mid-February of that year the last German garrison at Mora surrendered, ending the Siege of Mora.[27] German soldiers and civilians which had escaped to Spanish Guinea were treated amicably by the Spanish, who had only 180 militiamen in Río Muni and were unable to forcibly intern them. Most native Cameroonians remained in Muni but the Germans eventually moved to Fernando Po; some were eventually transported by Spain to the neutral Netherlands (from where they could reach home) before the war was over.[28] Many Cameroonians, including the paramount chief of the Beti people, moved to Madrid, where they lived as visiting nobility on German funds.[29]

Atrocities

German forces ordered a scorched earth policy against the indigenous Duala people to repress an alleged "people's war." Duala women were victims of wartime sexual violence by the German forces. Numerous killings were committed by German forces including in Jabassi where a white commander reportedly gave the order to "kill every native they saw."[10]

Aftermath

In February 1916, before the campaign ended, Britain and France agreed to divide Kamerun along the Picot Provisional Partition Line.[13] This resulted in Britain obtaining approximately one fifth of the colony situated on the Nigerian border. France gained Duala and most of the central plateau, which consisted of the majority of former German territory. The partition was accepted at the Paris Peace Conference and the former German colony became the League of Nations mandates of French Cameroon and British Cameroon by the Treaty of Versailles.[30]

Notes

- ^ Paice 2007, p. 299.

- ^ Karlheinz Graudenz, Hanns-Michael Schindler: Die deutschen Kolonien, P. 261

- ^ Karlheinz Graudenz, Hanns-Michael Schindler: Die deutschen Kolonien, P. 261

- ^ Strachan 2004, p. 31.

- ^ a b Killingray 2012, p. 116.

- ^ Golf Dornseif: Britisch-französische Rivalitäten im Kameruner Feldzug. (pdf; 2,6 MB) (Memento vom 28. September 2013 im Internet Archive)

- ^ Golf Dornseif: Britisch-französische Rivalitäten im Kameruner Feldzug. (pdf; 2,6 MB) (Memento vom 28. September 2013 im Internet Archive)

- ^ Moberly 1931, p. 426.

- ^ Erlikman 2004.

- ^ a b Njung, George Ndakwena (2016). Soldiers of their Own: Honor, Violence, Resistance and Conscription in Colonial Cameroon during the First World War (PDF). University of Michigan.

- ^ Moberly 1931, pp. 49–52.

- ^ Moberly 1931, pp. 46, 50.

- ^ a b Ngoh 2005, p. 349.

- ^ Killingray 2012, p. 117.

- ^ Moberly 1931, pp. 73–93.

- ^ Moberly 1931, pp. 170–173, 228–230, 421.

- ^ Moberly 1931, pp. 106–109.

- ^ Moberly 1931, pp. 93–97.

- ^ Moberly 1931, pp. 129, 156–157.

- ^ Moberly 1931, pp. 268–270.

- ^ Moberly 1931, pp. 294–299.

- ^ Moberly 1931, pp. 300–301, 322–323.

- ^ Moberly 1931, pp. 346–350.

- ^ Moberly 1931, pp. 388–293.

- ^ Moberly 1931, pp. 383–384.

- ^ Moberly 1931, pp. 405–419.

- ^ Moberly 1931, p. 421.

- ^ Moberly 1931, p. 412.

- ^ Quinn 1973, pp. 722–731.

- ^ Moberly 1931, p. 422.

References

- Elango, L. Z. (1985). "The Anglo-French "Condominium" in Cameroon, 1914–1916: The Myth and the Reality". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. XVIII (4). Boston, MA: Boston University African Studies Center: 656–673. doi:10.2307/218801. ISSN 0361-7882. JSTOR 218801.

- Erlikman, Vadim (2004). Poteri narodonaseleniia v XX veke : spravochnik (in Russian). Moscow: Russkai︠a︡ panorama. ISBN 5-93165-107-1.

- Killingray, D. (2012). John Horne (ed.). Companion to World War I. London: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-2386-0.

- Moberly, F. J. (1995) [1931]. Military Operations Togoland and the Cameroons 1914–1916 (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-235-7.

- Ngoh, V. J. (2005). "Cameroon (Kamerun): Colonial Period: German Rule". In Kevin Shillington (ed.). Encyclopedia of African History. Vol. I. New York: Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 1-57958-245-1.

- O'Neill, H. C. (1919) [1918]. The War in Africa 1914–1917 and in the Far East 1914 (reprint ed.). London: Longmans, Green. OCLC 786365389. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- Paice, E. (2009) [2007]. Tip and Run: The Untold Tragedy of the Great War in Africa (Phoenix ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-7538-2349-1.

- Quinn, F. (1973). "An African Reaction to World War I: The Beti of Cameroon". Cahiers d'Études Africaines. XIII (Cahier 52). Paris: Éditions EHESS (France). ISSN 1777-5353.

- Strachan, H. (2004). The First World War In Africa. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-925728-0.

Further reading

- Bryce, J. B.; Thompson, H.; Petrie, W. M. F. (1920). The Causes of the War: The Events of 1914–1915. The Book of History A History of all Nations From the Earliest Times to the Present, With Over 8,000 Illustrations. Vol. XVI. New York: The Grolier Society. OCLC 671596127. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- Burg, D. F.; Purcell, L. Edward (1998). Almanac of World War I. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky. ISBN 0-81312-745-9.

- Damis, F. von (1929). Auf dem Moraberge – Erinnerungen an die Kämpfe der 3. Kompagnie der ehemalige Kaiserlichen Schutztruppe für Kamerun (in German). Berlin: Deuß. OCLC 253272682.

- Dane, E. (1919). British Campaigns in Africa and the Pacific, 1914–1918. London: Hodder and Stoughton. OCLC 2460289. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Dornseif, Golf. British-French Rivalry in the Cameroon Campaign.

- Dobell, C. M. (1916). Cameroons Campaign Army Despatch. The London Gazette. HMSO. ISSN 0374-3721. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- Farwell, B. (1989). The Great War in Africa, 1914–1918. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-39330-564-3.

- Henry, H. B. (1999). Cameroon on a Clear Day. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library. ISBN 0-87808-293-X.

- Hilditch, A. N. (1915). Battle Sketches, 1914–1915. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 697895870. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- Innes, A. D.; Redway, Major; Wilson, H. W.; Low, S.; Wright, E. Hammerton, J. A. (ed.). Britain's Conquest of the German Cameroon. The War Illustrated Album De Luxe; the Story of the Great European War Told by Camera, Pen and Pencil. Vol. IV. pp. 1178–1182. OCLC 6460128. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- Reynolds, F. J.; Churchill, A. L.; Miller, F. T. (1916). "77". The Cameroons. The Story of the Great War. Vol. III. P. F. Collier & Son. OCLC 397036717.

External links

- Timeline of the Conquest of Kamerun

- Kamerun im Spiegel der deutschen Schutztruppe

- Kameruner Endkampf um die Festung Moraberg

- "The German Colony of Cameroon". Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- Soldiers of their Own: Honor, Violence, Resistance and Conscription in Colonial Cameroon during the First World War