Keith Godchaux

Keith Godchaux | |

|---|---|

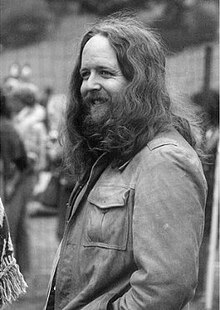

Godchaux in 1972 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Keith Richard Godchaux |

| Born | July 19, 1948 Seattle, Washington, US |

| Origin | San Francisco, California, US |

| Died | July 23, 1980 (aged 32) Marin County, California, US |

| Genres | Rock, psychedelia, rhythm and blues, blues, boogie woogie |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter |

| Instrument | Keyboard instruments |

| Years active | 1971–1980 |

| Formerly of | Grateful Dead, Jerry Garcia Band, Heart of Gold Band |

Keith Richard Godchaux (July 19, 1948 – July 23, 1980) was an American pianist best known for his tenure in the rock group the Grateful Dead from 1971 to 1979. Following their departure from the Dead, he and his wife Donna formed the Heart of Gold Band in 1980, but Godchaux died from injuries sustained in a car accident shortly after their first concert.

Biography

Godchaux was born in Seattle, Washington, and grew up in Concord, California, a regional suburban center within the East Bay of the San Francisco Bay Area. He began piano lessons at age five at the instigation of his father (a semi-professional musician) and subsequently played Dixieland and cocktail jazz in professional ensembles as a teenager. According to Godchaux, "I spent two years wearing dinner jackets and playing acoustic piano in country club bands and Dixieland groups...I also did piano bar gigs and put trios together to back singers in various places around the Bay Area...[playing] cocktail standards like 'Misty' the way jazz musicians resentfully play a song that's popular – that frustrated space... I just wasn't into it... I was looking for something real to get involved with – which wouldn't necessarily be music".[1] He met and married former FAME Studios session vocalist Donna Jean Thatcher in November 1970; their son Zion, of the band BoomBox, was born in 1974.

The couple introduced themselves to Jerry Garcia at a concert in August 1971; coincidentally, ailing keyboardist/vocalist Ron "Pigpen" McKernan (who would go on to play alongside Godchaux from December 1971 to June 1972) was unable to handle the rigors of the band's next tour. At the time, Godchaux was largely supported by his wife and irregularly employed as a lounge pianist in Walnut Creek, California. While he was largely uninterested in the popular music of the era and eschewed au courant jazz rock in favor of modal jazz, bebop, and swing, several sources[who?] claim that he collaborated with such rock acts as Dave Mason and James and the Good Brothers, a Canadian trio acquainted with the Grateful Dead.

According to Godchaux, "I first saw [the Grateful Dead] play with a bunch of my old lady's friends, who were real Grateful Dead freaks. I went to a concert with them and saw something I didn't know could be really happening... It was not like a mind-blowing far out, just a beautiful far out. Not exactly a choir of angels but some incredibly holy, pure and beautiful spiritual light. From then on, I was super turned-on that such a thing existed. This was about a year and a half ago, when I first met Donna... I knew I was related to them."[2][1] He was also known to Betty Cantor-Jackson, a Grateful Dead sound engineer, who produced James and the Good Brothers' debut album in 1970.

Remembering their initial meeting, drummer Bill Kreutzmann writes, "Then, around the same time that Pigpen entered the hospital, Jerry gave me a call telling me to get my ass down to the rehearsal space. He said there was a guy down there with him that I simply had to hear. Nobody else from the band was around, but almost immediately after I arrived, I knew that Jerry was right—this guy could really play piano."[3]

Although the band had employed several other keyboardists (including Howard Wales, Merl Saunders and Ned Lagin) as session musicians to augment McKernan's limited instrumental contributions following the departure of Tom Constanten in January 1970, Godchaux was invited to join the group as a permanent member in September 1971. He first performed publicly with the Dead on October 19, 1971, at the University of Minnesota's Northrup Auditorium.

After playing an upright piano and increasingly sporadic Hammond organ on the fall 1971 tour, Godchaux primarily played acoustic grand piano (including nine-foot Yamaha and Steinway instruments) at concerts from 1972 to 1974. Throughout this period, Godchaux's rented pianos were outfitted with a state-of-the-art pickup system designed by Carl Countryman. According to sound engineer Owsley Stanley, "The Countryman pickup worked by an electrostatic principle similar to the way a condenser mic works. It was charged with a very high voltage, and thus was very cantankerous to set up and use. It had a way of crackling in humid conditions and making other rather unmusical sounds if not set up just right, but when it worked it was truly brilliant." The control box also enabled Godchaux to use a wah-wah pedal with the instrument.[4] He added a Fender Rhodes electric piano in mid-1973 and briefly experimented with the Hammond organ again on the band's fall 1973 tour; the Rhodes piano would remain in his setup through 1976. Following the group's extended touring hiatus, he continued to use contractually-stipulated nine-foot Steinways furnished by the band's venues[5] in 1976 and early 1977 before switching exclusively to the Yamaha CP-70 electric grand piano in September 1977. The instrument's unwieldy tuning partially contributed to the shelving of the band's recordings of their 1978 engagement at the Giza Plateau for a planned live album.

Initially, Godchaux incorporated a richly melodic, fluid and boogie-woogie-influenced style that intuitively complemented the band's improvisational approach to rock music; critic Robert Christgau characterized his playing as "a cross between Chick Corea and Little Richard."[6] According to Garcia in a 1980 interview with Mark Rowland conducted shortly before Godchaux's death, "Keith is one of those guys who is sort of an idiot savant of the piano. He’s an excellent pianist but he didn’t really have a concept of music, of how the piano fit in with the rest of the band. We were constantly playing records for him and so forth but that wasn’t his gift. His gift was the keyboard, the piano itself."[7] Bassist Phil Lesh lauded his ability to "fit perfectly in the spaces between [our] parts," while Bill Kreutzmann was inspired by his "heart of music."[1]

Increasingly frayed from the vicissitudes of the rock and roll lifestyle, Godchaux gradually became dependent upon various drugs, most notably alcohol and heroin. Throughout the late 1970s, he was frequently embroiled in violent domestic conflicts with Donna, who also developed an alcohol use disorder. Following the Grateful Dead's 1975 hiatus, he largely yielded to a simpler comping-based approach with the group that eschewed his previously contrapuntal style in favor of emulating or ballasting Garcia's guitar parts. Despite occasional flirtations with synthesizers (most notably a Polymoog during the group's spring 1977 tour), this tendency was foregrounded by the reintegration of second drummer Mickey Hart, resulting in a heavily percussive sound with little sustain beyond Garcia's leads. However, Godchaux's playing in the Jerry Garcia Band – which had fewer instrumentalists and hence a more "open" sound – retained more elements of his earlier work with the Grateful Dead during this period.

In early 1978, rhythm guitarist Bob Weir began to perform slide guitar parts with an eye toward variegating the group's sound palette, with Weir concluding that "desperation is the mother of invention."[8] Garcia biographer Blair Jackson has also asserted that "the quality of Keith’s playing in the Dead fell off in ’78 and early ’79. It no longer had that sparkle and imagination that marked his best work (’72–’74). Much of what he played in his last year was basic, blocky, chordal stuff. I don’t hear many wrong notes but he’s not exactly out there on the edge taking chances and pushing the others, as he frequently did, in his own quiet way, in his peak Grateful Dead years. I guess the worst thing you could say about later-period Keith is that he was just taking up sonic space in the Dead’s overall sound. Did this affect the others? No doubt, though it can’t be measured."[9]

Eventually, according to Donna Jean Godchaux, "Keith and I decided we wanted to get out and start our own group or something else – anything else. So we played that benefit concert at Oakland [2/17/79] and then a few days later there was a meeting at our house and it was brought up whether we should stay in the band anymore...and we mutually decided we'd leave."[10] Keyboardist/vocalist Brent Mydland (who shared Godchaux's suburban East Bay background) had been groomed as their replacement for nearly a year in the Bob Weir Band and made his Grateful Dead debut at San Jose State University's Spartan Stadium on April 22, 1979.

During his tenure with the Dead, his only lead vocal and wholly original composition was "Let Me Sing Your Blues Away," a collaboration with lyricist Robert Hunter released on Wake of the Flood (1973). It was performed live six times, all in 1973. He also contributed to two group compositions on Blues for Allah (1975). Keith and Donna Godchaux issued the mostly self-written Keith & Donna album in 1975 with a core band including Garcia, Spooky Tooth bassist Chrissy Stewart and Wings drummer Denny Seiwell. The album was recorded at their home in Stinson Beach, California, where they lived in the 1970s.[11] A touring iteration of the Keith & Donna Band with Kreutzmann on drums and former Quicksilver Messenger Service equipment manager Stephen Schuster on saxophone frequently opened for Grateful Dead–related groups in 1975, allowing Garcia to sit in on several occasions.[12] Following the dissolution of this ensemble, the Godchauxs performed as part of the Jerry Garcia Band from 1976 to 1978. "Six Feet of Snow", a collaboration with Lowell George of Little Feat, was featured on the latter group's Down on the Farm (1979); George had recently produced the Grateful Dead's Shakedown Street (1978).

Following their departure from the Grateful Dead, the Godchauxs enjoyed an extended period of recuperation with their family in Alabama. He maintained a presence in the band's extended orbit, returning intermittently to California to perform alongside Kreutzmann in the Healy-Treece Band (a venture for Dan Healy, the band's longtime live audio engineer) and on at least one occasion with Hunter.[13] He also formed The Ghosts (later rechristened The Heart of Gold Band) with his wife; this Bay Area-based aggregation eventually came to include a young Steve Kimock on guitar.

Godchaux sustained massive head injuries in an auto accident while being driven home on his birthday by noted tie-dye artist Courtenay Pollock (who was hosting the Godchauxs at his home in San Geronimo, California as they worked with their new band) in July 1980. Shortly before the accident, he professed to Pollock that he was "the happiest I've ever felt in my life."[14] He died at the age of 32 on July 23, 1980, four days after his birthday.[15]

In 1994, he was inducted, posthumously, into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of the Grateful Dead.

Legacy

According to Phil Lesh, some fans consider the years that Keith joined through the touring hiatus in 1974 to be the best years of the Grateful Dead. In his book he writes, "Keith turned into a fire-breathing demon about halfway through the fall [1971] tour—not only following the band effortlessly through all our endlessly bifurcating highways and byways, but grabbing the ball and running with it, leading us into unknown regions and setting the stage for what many heads consider the peak years of the Grateful Dead. With Keith, we became the turbocharged turn-on-a-dime Grateful Dead that had only been hinted at before, but the music also became warmer and more organic, almost but not quite filling the hole Pig's absence had left."[16] Lesh has further clarified that, to him, the band was "never quite the same" after coming back from their touring hiatus in 1975.[17]

Bill Kreutzmann writes about Keith, "He was one of the best, if not the best, keyboardist that I’ve had the honor of playing with. The Grateful Dead have played with some really good ones over the years, like Bruce Hornsby and Brent Mydland, but this guy was just outrageous. He was really competent too, in that he could pick up whatever Jerry and I started playing that day, and just run with it. He didn’t need to know the material first. He could learn songs before he was even done hearing them for the first time. And he could play just about anything."[3]

References

- ^ a b c "Grateful Dead Guide: How Keith Joined". DeadEssays.blogspot.com. September 4, 2012. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ Jackson, Blair. "Chapter 12: Wait Until That Deal Come 'Round". Garcia: An American Life. Outtakes, Afterthoughts and Other Cool Stuff. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Kreutzmann, Bill; Eisen, Benjy (2015). Deal: My Three Decades of Drumming, Dreams, and Drugs with the Grateful Dead (1st ed.). New York. ISBN 978-1-250-03379-6. OCLC 904047411.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Jackson, B. (2006). Grateful Dead Gear: The Band's Instruments, Sound Systems, and Recording Sessions from 1965 to 1995. Backbeat Books. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-879-30893-3. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Conners, Peter (2017). Cornell '77: The Music, the Myth, and the Magnificence of the Grateful Dead's Concert at Barton Hall. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-501-71256-2.

- ^ Christgau, Robert, Ace (review), robertchristgau.com, retrieved October 30, 2016

- ^ "Jerry Garcia's Middle Finger: "Bloody Hell"". jgmf.blogspot.com. January 18, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Trager, O. (1997). The American Book of the Dead. Touchstone. p. 353. ISBN 978-0-684-81402-5. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ "Blair's Golden Road Blog - Keith and Donna's Last Days with the Dead | Grateful Dead". dead.net. September 21, 2012. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Jackson, B. (2000). Garcia: An American Life. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-101-66406-3. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Grateful Dead Family Discography: Keith and Donna Godchaux, accessed February 2, 2008.

- ^ "Lost Live Dead: Keith and Donna Band, Tour History 1975". lostlivedead.blogspot.com. September 24, 2009. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ "Hooterollin' Around: April 2014". hooterollin.blogspot.com. April 11, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Browne, David (2015). So Many Roads: The Life and Times of the Grateful Dead. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82171-4. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- ^ Tobler, John (1992). NME Rock 'N' Roll Years (1st ed.). London: Reed International Books Ltd. p. 344. CN 5585.

- ^ Lesh, Phil (2006). Searching for the sound : my life with the Grateful Dead (1st Back Bay paperback ed.). New York: Back Bay Books. ISBN 0316154490. OCLC 69106660.

- ^ Fricke, David (August 17, 2016). "The Last Word: Phil Lesh on Favorite Jerry Garcia Memory, Sci-Fi". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

External links

- Keith Godchaux Home Archived August 17, 2010, at the Wayback Machine at Dead101.com

- Official Grateful Dead Website

- Keith Godchaux discography at Discogs