King Kong (1933)

| King Kong | |

|---|---|

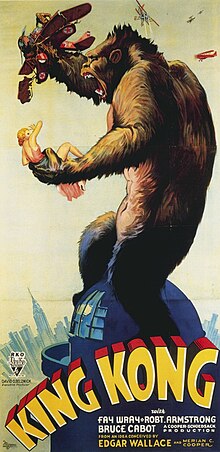

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by | Ted Cheesman |

| Music by | Max Steiner |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 100 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $672,254.75[2] |

| Box office | $5.3 million[2] (equivalent to $124.75 million in 2023)[3] |

King Kong is a 1933 American pre-Code adventure romance monster film[4] directed and produced by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, with special effects by Willis H. O'Brien and music by Max Steiner. Produced and distributed by RKO Radio Pictures, it is the first film in the King Kong franchise. The film stars Fay Wray, Robert Armstrong, and Bruce Cabot. The film follows a giant ape dubbed Kong who is offered a beautiful young woman as a sacrifice.

King Kong opened in New York City on March 2, 1933, to rave reviews, with praise for its stop-motion animation and score. In 1991, it was deemed "culturally, historically and aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.[5][6] It is ranked by Rotten Tomatoes as the greatest horror film of all time[7] and the fifty-sixth greatest film of all time.[8] A sequel, Son of Kong, was made the same year as the original film, and several more films have been made, including two remakes in 1976 and 2005.

Plot

In New York Harbor, filmmaker Carl Denham, known for wildlife films in remote exotic locations, is chartering Captain Englehorn's ship, the Venture, for his new project. However, he is unable to secure an actress for a female role he has been reluctant to disclose. In the streets of New York City, he finds Ann Darrow and promises her "the thrill of a lifetime". The Venture sets off, during which Denham reveals that their destination is in fact an uncharted island with a mountain the shape of a skull. He alludes to a mysterious entity named Kong, rumored to dwell on the island. The crew arrive and anchor offshore. They encounter a native village, separated from the rest of the island by an enormous stone wall with a large wooden gate. They witness a group of natives preparing to sacrifice a young woman termed the "bride of Kong". The intruders are spotted and the native chief stops the ceremony. When he sees the blonde-haired Ann, he offers to trade six of his tribal women for the "golden woman". They refuse him and return to the ship.

That night, after the ship's first mate, Jack Driscoll, admits his love for Ann, the natives kidnap Ann from the ship and take her through the gate and onto an altar, where she is offered to Kong, who is revealed to be a giant gorilla. Kong carries a terrified Ann away as Denham, Jack and some volunteers give chase. The men encounter living dinosaurs; they manage to kill a charging Stegosaurus, but are attacked by an aggressive Brontosaurus and eventually Kong himself, leaving Jack and Denham as the only survivors. After Kong slays a Tyrannosaurus to save Ann, Jack continues to follow them while Denham returns to the village. Upon arriving in Kong's mountain lair, Ann is menaced by a serpent-like Elasmosaurus, which Kong also kills. When a Pteranodon tries to fly away with Ann, and is killed by Kong, Jack saves her and they climb down a vine dangling from a cliff ledge. When Kong starts pulling them back up, the two drop into the water below; they flee through the jungle back to the village, where Denham, Englehorn, and the surviving crewmen await. Kong, following, breaks open the gate and relentlessly rampages through the village. Onshore, Denham, determined to bring Kong back alive, renders him unconscious with a gas bomb.

Shackled in chains, Kong is taken to New York City and presented to a Broadway theatre audience as "Kong, the Eighth Wonder of the World!" Ann and Jack join him on stage, surrounded by press photographers. The ensuing flash photography causes Kong to break loose as the audience flees in terror. Ann is whisked away to a hotel room on a high floor, but Kong, scaling the building, reclaims her. He makes his way through the city with Ann in his grasp, wrecking a crowded elevated train and begins climbing the Empire State Building. Jack suggests to police for airplanes to shoot Kong off the building, without hitting Ann. Four biplanes take off; seeing the planes arrive, Jack becomes agitated for Ann's safety and rushes inside with Denham. At the top, Kong is shot at by the planes, as he begins swatting at them. Kong destroys one, but is wounded by the gunfire. After he gazes at Ann, he is shot more, loses his strength and plummets to the streets below; Jack reunites with Ann. Denham heads back down and is allowed through a crowd surrounding Kong's corpse in the street. When a policeman remarks that the planes got him, Denham states, "Oh, no, it wasn't the airplanes. It was Beauty killed the Beast."

Cast

- Fay Wray as Ann Darrow

- Robert Armstrong as Carl Denham

- Bruce Cabot as John "Jack" Driscoll

- Frank Reicher as Captain Englehorn

- Sam Hardy as Charles Weston

- Victor Wong as Charlie

- James Flavin as Second Mate Briggs

- Etta McDaniel as The Native Mother

- Everett Brown as The Native In An Ape Costume

- Noble Johnson as The Native Chief

- Steve Clemente as The Witch Doctor

Production

Crew

- Merian C. Cooper – co-director, producer

- Ernest B. Schoedsack – co-director, producer

- David O. Selznick – executive producer

- Willis H. O'Brien – chief technician

- Archie Marshek – production assistant

- Harry Redmond Jr. – special effects

- Murray Spivack – sound effects

- Van Nest Polglase – supervising art director

- Clem Portman – sound recording mixer

- Mel Berns – chief makeup supervisor

Personnel taken from King Kong: The History of a Movie Icon From Fay Wray to Peter Jackson.[9]

Development

King Kong producer Ernest B. Schoedsack had earlier monkey experience directing Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness (1927), also with Merian C. Cooper, and Rango (1931), both of which prominently featured monkeys in authentic jungle settings. Capitalizing on this trend, Congo Pictures released the hoax documentary Ingagi (1930), advertising the film as "an authentic incontestable celluloid document showing the sacrifice of a living woman to mammoth gorillas." Ingagi is now often recognized as a racial exploitation film as it implicitly depicted black women having sex with gorillas, and baby offspring that looked more ape than human.[11] The film was an immediate hit, and by some estimates, it was one of the highest-grossing films of the 1930s at over $4 million. Although Cooper never listed Ingagi among his influences for King Kong, it has long been held that RKO greenlighted Kong because of the bottom-line example of Ingagi and the formula that "gorillas plus sexy women in peril equals enormous profits."[12]

Special effects

King Kong is well known for its groundbreaking use of special effects, such as stop-motion animation, matte painting, rear projection and miniatures, all of which were conceived decades before the digital age.[13]

The numerous prehistoric creatures inhabiting the Island were brought to life through the use of stop-motion animation by Willis H. O'Brien and his assistant animator, Buzz Gibson.[14] The stop-motion animation scenes were painstaking and difficult to achieve and complete. The special effects crew realized that they could not stop because it would make the movements of the creatures seem inconsistent and the lighting would not have the same intensity over the many days it took to fully animate a finished sequence. A device called the surface gauge was used in order to keep track of the stop-motion animation performance. The iconic fight between Kong and the Tyrannosaurus took seven weeks to be completed.

The backdrop of the island seen when the Venture crew first arrives was painted on glass by matte painters Henry Hillinck, Mario Larrinaga, and Byron L. Crabbe. The scene was then composited with separate bird elements and rear-projected behind the ship and the actors. The background of the scenes in the jungle (a miniature set) was also painted on several layers of glass to convey the illusion of deep and dense jungle foliage.[15]

The most difficult task for the special effects crew to achieve was to make live-action footage interact with separately filmed stop-motion animation, making the interaction between the humans and the creatures of the island seem believable. The most simple of these effects were accomplished by exposing part of the frame, then running the same piece of the film through the camera again by exposing the other part of the frame with a different image. The most complex shots, where the live-action actors interacted with the stop-motion animation, were achieved via two different techniques, the Dunning process and the Williams process, in order to produce the effect of a traveling matte.[16] The Dunning process, invented by cinematographer Carroll H. Dunning, employed the use of blue and yellow lights that were filtered and photographed into the black-and-white film. Bi-packing of the camera was used for these types of effects. With it, the special effects crew could combine two strips of different films at the same time, creating the final composite shot in the camera.[17] It was used in the climactic scene where one of the planes attacking Kong crashes from the top of the Empire State Building, and in the scene where natives are running through the foreground, while Kong is fighting other natives at the wall.[citation needed]

On the other hand, the Williams process, invented by cinematographer Frank D. Williams, did not require a system of colored lights and could be used for wider shots. It was used in the scene where Kong is shaking the sailors off the log, as well as the scene where Kong pushes the gates open. The Williams process did not use bipacking, but rather an optical printer, the first such device that synchronized a projector with a camera, so that several strips of film could be combined into a single composited image. Through the use of the optical printer, the special effects crew could film the foreground, the stop-motion animation, the live-action footage, and the background, and combine all of those elements into one single shot, eliminating the need to create the effects in the camera.[18]

Another technique that was used in combining live actors and stop-motion animation was rear-screen projection. The actor would have a translucent screen behind him where a projector would project footage onto the back of the translucent screen.[19] The translucent screen was developed by Sidney Saunders and Fred Jackman, who received a Special Achievement Oscar. It was used in the scene where Kong and the Tyrannosaurus fight while Ann watches from the branches of a nearby tree. The stop-motion animation was filmed first. Fay Wray then spent a twenty-two-hour period sitting in a fake tree acting out her observation of the battle, which was projected onto the translucent screen while the camera filmed her witnessing the projected stop-motion battle. She was sore for days after the shoot. The same process was also used for the scene where sailors from the Venture kill a Stegosaurus.[20]

O'Brien and his special effects crew also devised a way to use rear projection in miniature sets. A tiny screen was built into the miniature onto which live-action footage would then be projected.[19] A fan was used to prevent the footage that was projected from melting or catching fire. This miniature rear projection was used in the scene where Kong is trying to grab Driscoll, who is hiding in a cave. The scene where Kong puts Ann at the top of a tree switched from a puppet in Kong's hand to projected footage of Ann sitting.[citation needed]

The scene where Kong fights the Tanystropheus in his lair was likely the most significant special effects achievement of the film, due to the way in which all of the elements in the sequence work together at the same time. The scene was accomplished through the combination of a miniature set, stop-motion animation, background matte paintings, real water, foreground rocks with bubbling mud, smoke, and two miniature rear screen projections of Driscoll and Ann.[citation needed]

Over the years, some media reports have alleged that in certain scenes Kong was played by an actor wearing a gorilla suit.[21][22] However, film historians have generally agreed that all scenes involving Kong were achieved with animated models,[23][24] except for the "closeups" of Kong's face and upper body which are dispersed throughout the film. These shots were accomplished by filming a "full size" mechanical model of Kong's head and shoulders. Operators could manipulate the eyes and mouth to simulate a living monster. These shots can be identified immediately in two ways: the action is very smooth (not stop-motion jittery) and the footage is extremely sharp and clear because of the size of the subject being photographed.

Post-production

Murray Spivack provided the sound effects for the film. Kong's roar was created by mixing the recorded vocals of captive lions and tigers, subsequently played backward slowly. Spivak himself provided Kong's "love grunts" by grunting into a megaphone and playing it at a slow speed. For the huge ape's footsteps, Spivak stomped across a gravel-filled box with plungers wrapped in foam attached to his own feet, while the sounds of his chest beats were recorded by Spivak hitting his assistant (who had a microphone held to his back) on the chest with a drumstick. Spivak created the hisses and croaks of the dinosaurs with an air compressor for the former and his own vocals for the latter. The vocalizations of the Tyrannosaurus were additionally mixed in with puma growls while bird squawks were used for the Pteranodon. Spivak also provided the numerous screams of the various sailors. Fay Wray herself provided all of her character's screams in a single recording session.[25][26]

The score was unlike any that came before and marked a significant change in the history of film music. King Kong's score was the first feature-length musical score written for an American "talkie" film, the first major Hollywood film to have a thematic score rather than background music, the first to mark the use of a 46-piece orchestra and the first to be recorded on three separate tracks (sound effects, dialogue, and music). Steiner used a number of new film scoring techniques, such as drawing upon opera conventions for his use of leitmotifs.[27] Over the years, Steiner's score was recorded by multiple record labels and the original motion picture soundtrack has been issued on a compact disc.[28]

Release

Censorship and restorations

The Production Code's stricter decency rules were put into effect in Hollywood after the film's 1933 premiere and it was progressively censored further, with several scenes being either trimmed or excised altogether for the 1938-1956 rereleases. These scenes were as follows:

- The Brontosaurus mauling crewmen in the water, chasing one up a tree and killing him.

- Kong undressing Ann Darrow and sniffing his fingers.

- Kong biting and stepping on natives when he attacks the village.

- Kong biting a man in New York.

- Kong mistaking a sleeping woman for Ann and dropping her to her death, after realizing his mistake.

- An additional scene portraying giant insects, spiders, a reptile-like predator and a tentacled creature devouring the crew members shaken off the log by Kong onto the floor of the canyon below was deemed too gruesome by RKO even by pre-Code standards (though Cooper also thought it "stopped the story"), and thus the scene was studio self-censored prior to the original release. The footage is considered lost, with the exception of only a few stills and pre-production drawings.[25][29] There are also claims that it was never filmed and was only in the script and novelization.[30]

RKO did not preserve copies of the film's negative or release prints with the excised footage, and the cut scenes were considered lost for many years. In 1969, a 16mm print, including the censored footage, was found in Philadelphia. The cut scenes were added to the film, restoring it to its original theatrical running time of 100 minutes. This version was re-released to art houses by Janus Films in 1970.[25] Over the next two decades, Universal Studios undertook further photochemical restoration of King Kong. This was based on a 1942 release print with missing censor cuts taken from a 1937 print, which "contained heavy vertical scratches from projection."[31] An original release print located in the UK in the 1980s was found to contain the cut scenes in better quality. After a 6-year worldwide search for the best surviving materials, a further, fully digital restoration utilizing 4K resolution scanning was completed by Warner Bros. in 2005.[32] This restoration also had a 4-minute overture added, bringing the overall running time to 104 minutes.

Somewhat controversially, King Kong was colorized for a 1989 Turner Home Entertainment video release.[33] The following year, this colorized version was shown on Turner's TNT channel.[34]

Television

After the 1956 re-release, the film was sold to television and was first broadcast on March 5, 1956.[35]

Home media

In 1984, King Kong was one of the first films to be released on LaserDisc by the Criterion Collection, and was the first movie to have an audio commentary track included.[36] Criterion's audio commentary was by film historian Ron Haver in 1985. Image Entertainment released another LaserDisc, this time with a commentary by film historian and soundtrack producer Paul Mandell. The Haver commentary was preserved in full on the FilmStruck streaming service. King Kong had numerous VHS and LaserDisc releases of varying quality prior to receiving an official studio release on DVD. Those included a Turner 60th-anniversary edition in 1993 featuring a front cover that had the sound effect of Kong roaring when his chest was pressed. It also included a 25-minute documentary, It Was Beauty Killed the Beast (1992). The documentary is also available on two different UK King Kong DVDs, while the colorized version is available on DVD in the UK and Italy.[37] Warner Home Video re-released the black and white version on VHS in 1998 and again in 1999 under the Warner Bros. Classics label, with this release including the 25-minute 1992 documentary.[citation needed]

In 2005, Warner Bros. released its digital restoration of King Kong in a US 2-disc Special Edition DVD, coinciding with the theatrical release of Peter Jackson's remake. It had numerous extra features, including a new, third audio commentary by visual effects artists Ray Harryhausen and Ken Ralston, with archival excerpts from actress Fay Wray and producer/director Merian C. Cooper. Warners issued identical DVDs in 2006 in Australia and New Zealand, followed by a US digibook-packaged Blu-ray in 2010.[38] In 2014, the Blu-ray was repackaged with three unrelated films in a 4 Film Favorites: Colossal Monster Collection. At present, Universal holds worldwide rights to Kong's home video releases outside of North America, Latin America, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand. All of Universal's releases only contain the earlier, 100-minute, pre-2005 restoration.[32]

Reception

Box office

The film was a box-office success, earning about $5 million in worldwide rentals on its initial release, and an opening weekend estimated at $90,000. Receipts fell by up to 50% during the second week of the film's release because of the national "bank holiday" declared by President Franklin D. Roosevelt's during his first days in office.[39] During the film's first run it made a profit of $650,000.[2] Prior to the 1952 re-release, the film is reported to have worldwide rentals of $2,847,000 including $1,070,000 from the United States and Canada and profits of $1,310,000.[2] After the 1952 re-release, Variety estimated the film had earned an additional $1.6 million in the United States and Canada, bringing its total to $3.9 million in cumulative domestic rentals.[40] Profits from the 1952 re-release were estimated by the studio at $2.5 million.[2]

Critical response

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 97% based on 116 reviews, with an average rating of 9/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "King Kong explores the soul of a monster – making audiences scream and cry throughout the film – in large part due to Kong's breakthrough special effects."[41] On Metacritic the film has a weighted average score of 92 out of 100, based on 12 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[42]

Variety thought the film was a powerful adventure.[43] The New York Times gave readers an enthusiastic account of the plot and thought the film a fascinating adventure.[44] John Mosher of The New Yorker called it "ridiculous," but wrote that there were "many scenes in this picture that are certainly diverting."[45] The New York World-Telegram said it was "one of the very best of all the screen thrillers, done with all the cinema's slickest camera tricks."[46] The Chicago Tribune called it "one of the most original, thrilling and mammoth novelties to emerge from a movie studio."[47]

On February 3, 2002, Roger Ebert included King Kong in his "Great Movies" list, writing that "In modern times the movie has aged, as critic James Berardinelli observes, and 'advances in technology and acting have dated aspects of the production.' Yes, but in the very artificiality of some of the special effects, there is a creepiness that isn't there in today's slick, flawless, computer-aided images... Even allowing for its slow start, wooden acting, and wall-to-wall screaming, there is something ageless and primeval about King Kong that still somehow works."[48]

Criticism of racism and sexism

In the 19th and early 20th century, people of African descent were commonly represented visually as ape-like, a metaphor that fit racist stereotypes further bolstered by the emergence of scientific racism.[49] Early films frequently mirrored racial tensions. While King Kong is often compared to the story of Beauty and the Beast, many film scholars have argued that the film was a cautionary tale about interracial romance, in which the film's "carrier of blackness is not a human being, but an ape."[50][51]

Cooper and Schoedsack rejected any allegorical interpretations, insisting in interviews that the film's story contained no hidden meanings.[52] In an interview, which was published posthumously, Cooper explained the deeper meaning of the film. The inspiration for the climactic scene came when, "as he was leaving his office in Manhattan, he heard the sound of an airplane motor. He reflexively looked up as the sun glinted off the wings of a plane flying extremely close to the tallest building in the city... he realized if he placed the giant gorilla on top of the tallest building in the world and had him shot down by the most modern of weapons, the armed airplane, he would have a story of the primitive doomed by modern civilization."[53]

The film was initially banned in Nazi Germany, with the censors describing it as an "attack against the nerves of the German people" and a "violation of German race feeling". However, according to confidant Ernst Hanfstaengl, Adolf Hitler was "fascinated" by the film and saw it several times.[54]

The film was later criticized for racist stereotyping of the natives and Charlie the Cook, played by Victor Wong, who upon discovering the kidnapping of Ann Darrow, exclaims "Crazy black man been here!".[55] The film has been noted for its depiction of Ann as a damsel in distress. In her autobiography, Wray wrote that Ann's screaming was too much.[56] However, Nick Hilton in The Independent stated that the film "may look a little foolish to us (not to mention racist, sexist and, shall we say, symbolically naive) but it still packs a visceral wallop",[57] while Ryan Britt felt that critics were willing to overlook the film's problematic aspects as "just unattractive byproducts of the era in which the film was made...that the meta-fictional aspects almost excuse some of the cultural insensitivity".[58] In 2013 an article entitled "11 of The Most Racist Movies Ever Made" described the film's natives "as subhuman, or primate... (not) even have a distinct way of communicating..." The article also brought up the racial allegory between Kong and black men, particularly how Kong "meets his demise due to his insatiable desire for a white woman".[59]

Legacy

The film has since received some significant honors. In 1975, Kong was named one of the 50 best American films by the American Film Institute. In 1981, a video game titled Donkey Kong, starring a character with similarities to Kong, was released. In 1991, the film was deemed "culturally, historically and aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry.[61][62] In 1998, the AFI ranked the film #43 on its list of the 100 greatest movies of all time.[25][63]

The film's stop motion effects by Willis H. O'Brien revolutionized special effects, leaving a lasting impact on the film industry worldwide and inspired other genre films such as Mighty Joe Young, The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms,[64] Creature from the Black Lagoon,[65] Mothra,[66] and Jurassic Park.[67][68] The film was also one of the biggest inspirations for Godzilla, with Tomoyuki Tanaka stating, "I felt like doing something big. That was my motivation. I thought of different ideas. I like monster movies, and I was influenced by King Kong."[69]

Daiei Film, the company which later produced Gamera and Daimajin and other tokusatsu films distributed the 1952 re-released edition of King Kong in 1952, making it the first post-war release of monster movies in Japan. The company also distributed The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms in Japan in 1954, and these distributions presumably influenced productions of both Godzilla and Gamera franchises.[60]

It has been suggested by author Daniel Loxton that King Kong inspired the modern day legend of the Loch Ness Monster.[70][71]

American Film Institute Lists

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – #43

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – #12

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions – #24

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- Kong – Nominated Villain

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "Oh, no, it wasn't the airplanes. It was Beauty killed the Beast." – #84

- AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – #13

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – #41

- AFI's 10 Top 10 – #4 Fantasy Film

Sequel and franchise

The film and characters inspired imitations and installments. Son of Kong, a sequel was fast-tracked and released the same year of the first film's release. In the 1960s, RKO licensed the King Kong character to Japanese studio Toho which made two films, King Kong vs. Godzilla, the third film in Toho's long-running Godzilla series, and King Kong Escapes, both directed by Ishirō Honda. These films are mostly unrelated to the original and follow a very different style.

In 1976, producer Dino De Laurentiis released a modern remake of King Kong, following the same basic plot, but moving the setting to the present day and changing many details. The remake was followed by a 1986 sequel King Kong Lives.

In 1998, a loosely-adapted direct-to-video animated version, The Mighty Kong, was distributed by Warner Bros.

In 2005, Universal Pictures released another remake of King Kong, co-written and directed by Peter Jackson, which is set in 1933, as in the original film.

Legendary Pictures and Warner Bros. made Kong: Skull Island (2017), which serves as part of a cinematic universe, MonsterVerse, followed by the sequels Godzilla vs. Kong (2021), and Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire (2024).

See also

- List of cult films

- List of films featuring dinosaurs

- List of films featuring giant monsters

- List of highest-grossing films

- List of stop motion films

- 1933 in film

- The Lost World (1925)

- Stark Mad (1929)

- Ingagi (1930)

- Mighty Joe Young (1949)

References

- ^ King Kong at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ a b c d e * Jewel, Richard (1994). "RKO Film Grosses: 1931–1951". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 14 (1): 39.

1933 release: $1,856,000; 1938 release: $306,000; 1944 release: $685,000

- "King Kong (1933) – Notes". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

1952 release: $2,500,000; budget: $672,254.75

- "King Kong (1933) – Notes". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Sprague, Mike (April 7, 2021). "Horror History: KING KONG (1933) Is Now 88 Years Old". Dread Central. Archived from the original on September 9, 2021. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- ^ Daniel Eagan, (2010). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc, New York, NY p.22

- ^ Kehr, Dave (September 26, 1991). "U.S. FILM REGISTRY ADDS 25 SIGNIFICANT MOVIES". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ "Best Horror Movies – King Kong (1933)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on April 1, 2010. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ "Top 100 Movies of All Time – Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ Morton 2005, p. 13.

- ^ Orville Goldner, George E Turner (1975). Making of King Kong: The Story Behind a Film Classic. ISBN 0498015106. See also Spawn of Skull Island (2002). ISBN 1887664459

- ^ Gerald Peary, 'Missing Links: The Jungle Origins of King Kong' (1976) Archived January 3, 2013, at archive.today Gerald Peary: Film Reviews, Interviews, Essays, and Sundry Miscellany, 2004.

- ^ Erish, Andrew (January 8, 2006). "Illegitimate Dad of King Kong". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 14, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ Wasko, Janet. (2003). How Hollywood Works. California: SAGE Publications Ltd. p.53.

- ^ Bordwell, David, Thompson, Kristin, Smith, Jeff. (2017). Film Art: An Introduction. New York: McGraw-Hill. p.388.

- ^ Harryhausen, Ray. (1983). Animating the Ape. In: Lloyd, Ann. (ed.) Movies of the Thirties. UK: Orbis Publishing Ltd. p.173.

- ^ Corrigan, Timothy, White, Patricia. (2015). The Film Experience. New York: Bedford/St. Martin's. pp.120–121.

- ^ Harryhausen 172–173

- ^ Dyson, Jeremy. (1997). Bright Darkness: The Lost Art of the Supernatural Horror Film. London: Cassell. p.38.

- ^ a b Harryhausen 173

- ^ "King Kong | Giant Ape, Stop-Motion Animation, Adventure | Britannica". www.britannica.com. November 22, 2024. Retrieved December 27, 2024.

- ^ "Charlie Gemora, 58, had King Kong role". The New York Times. August 20, 1961. Archived from the original on March 18, 2022. Retrieved February 10, 2017.(subscription required)

- ^ Greene, Bob (November 27, 1990). "Saying so long to Mr. Kong". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- ^ Glut, Donald F. (2001). Jurassic Classics: A Collection of Saurian Essays and Mesozoic Musings. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 192. ISBN 9780786462469.

Over the years, various actors have claimed to have played Kong in this [Empire State Building] scene, including a virtually unknown performer named Carmen Nigro (AKA Ken Roady), and also noted gorilla impersonator Charles Gemora... In Nigro's case, the claim seems to have been simply fraudulent, in Gemora's, the inaccurate claim was apparently based on the actor's memory of playing a giant ape in a never-completed King Kong spoof entitled The Lost Island.

- ^ Glut, Donald F. (2005). "His Majesty, King Kong - IV". In Woods, Paul A. (ed.). King Kong Cometh!. London: Plexus. p. 64. ISBN 9780859653626.

Cooper denied any performance by an actor in a gorilla costume in King Kong... Perhaps a human actor was used in a bit of forgotten test footage before the film went into production, but thus far the matter remains a mystery.

- ^ a b c d Morton 2005, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Von Gunden, Kenneth (2001). Flights of Fancy: The Great Fantasy Films. McFarland. p. 117. ISBN 9780786412143.

- ^ Helvering, David Allen; The University of Iowa (2007). Functions of dialogue underscoring in American feature film. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-549-23504-0. Archived from the original on January 5, 2014. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ "KING KONG - 75th anniversary of the film and Max Steiner's great film score". Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ Wednesday, WTM • (December 12, 2018). "The Lost Scene from 1933's King Kong - the Spider Pit". Neatorama. Archived from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ "King Kong (non-existent cut content of Pre-code monster adventure film; 1933) - The Lost Media Wiki". April 2, 2024. Archived from the original on April 2, 2024. Retrieved April 28, 2024.

- ^ Millimeter Magazine article, 1 January 2006 Archived May 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: March 15, 2012

- ^ a b "Robert A. Harris On King Kong" Archived August 13, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: March 15, 2012,

- ^ Wickstrom, Andy (February 17, 1989). "COLORIZED KING KONG MAY BUG FANS". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ "King Kong: Miscellaneous Notes" at TCM Archived May 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: March 15, 2012

- ^ Rainho, Manny (March 2015). "This Month in Movie History". Classic Images (477): 26.

- ^ "If DVD killed the film star, Criterion honors the ghost". The Denver Post. August 24, 2005. Archived from the original on November 11, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ^ DVDCompare.com: King Kong (1933) Archived November 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: April 8, 2012

- ^ DVDBeaver.com King Kong comparison Archived April 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: June 14, 2015

- ^ Ahamed, Liaquat (2009). Lords of Finance. Penguin Books. p. 452. ISBN 9780143116806.

- ^ "'Gone,' With $26,000,000, Still Tops All-Timers, Greatest Show Heads 1952". Variety. January 21, 1953. p. 4.

- ^ "King Kong". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on December 30, 2009. Retrieved November 19, 2022.

- ^ "King Kong (1933) Reviews – Metacritic". Metacritic.com. Metacritic. Archived from the original on July 29, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ Bigelow, Joe (March 6, 1933). "King Kong". Variety. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ Hall

- ^ Mosher, John (March 11, 1933). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. New York: F-R Publishing Corporation. p. 56.

- ^ "New York Reviews". The Hollywood Reporter. Los Angeles. March 7, 1933. p. 2.

- ^ "Monster Ape Packs Thrills in New Talkie". Chicago Tribune. Chicago. April 23, 1933. p. Part 7, p.8.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (February 3, 2002). "King Kong movie review & film summary (1933)". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2013. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ Grant, Elizabeth. (1996). 'Here Comes the Bride.' In: Grant, Barry Keith (ed.). The Dread of Difference: Gender and the Horror Film. Austin: University of Texas Press. P.373

- ^ Goff, Phillip Atiba; Eberhardt, Jennifer L.; Williams, Melissa J.; Jackson, Matthew Christian (2008). "Not yet human: Implicit knowledge, historical dehumanization, and contemporary consequences". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 94 (2): 293. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.292. ISSN 1939-1315. PMID 18211178.

- ^ Kuhn, Annette. (2007). King Kong. In: Cook, Pam. (ed.) The Cinema Book. London: British Film Institute. P,41. and Robinson, D. (1983). King Kong. In: Lloyd, A. (ed.) Movies of the Thirties. Orbis Publishing Ltd. p.58.

- ^ Cynthia Marie Erb (2009). Tracking King Kong: A Hollywood Icon in World Culture. Wayne State University Press. p. xvii. ISBN 978-0-8143-3430-0. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- ^ Haver, Ron (December 1976). "Merian C. Cooper: The First King of Kong". American Film Magazine. New York: American Film Institute. p. 18. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2019.

- ^ Germany, SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg (December 2, 2015). "Hitlers Kino: "Führer"-Faible für Garbo oder Dick und Doof". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

{cite news}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "KING KONG: SPECIAL EDITION". www.starburstmagazine.com/. June 29, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ "King Kong and Fay Wray". Hollywood Progressive. March 2, 2023.

- ^ "The first (And original) King Kong". Independent.co.uk. December 10, 2005.

- ^ "Think He's Crazy? Nah, Just Enthusiastic. Rewatching King Kong (1933)". October 24, 2011.

- ^ "11 of The Most Racist Movies Ever Made". Atlanta Black Star. November 22, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2024.

- ^ a b Hisayuki Ui, January 1, 1994, From Gamera to Daimajin: all of Daiei tokusatsu films, p.63, Kindaieigasha

- ^ Eagan 22

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on November 10, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ "AFI's 100 YEARS...100 MOVIES". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on December 13, 2020. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ Rovin, Jeff (1989). The Encyclopedia of Monsters. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-1824-3.

- ^ Weaver, Tom (2014). The Creature Chronicles: Exploring the Black Lagoon Trilogy. McFarland & Company. p. 30. ISBN 978-0786494187.

- ^ Memories of Ishiro Honda. Twenty Years After The Passing Of Godzilla's Famed Director by Hajime Ishida. Famous Monsters of Filmland #269. Movieland Classics LLC, 2013. Pg. 20

- ^ Mottram, James (2021). Jurassic Park: The Ultimate Visual History. Insight Editions. p. 17. ISBN 978-1683835455.

- ^ Jones, James Earl (Host) (1995). The Making of Jurassic Park (VHS). Universal.

- ^ Wudunn, Sheryl (April 4, 1997). "Tomoyuki Tanaka, the Creator of Godzilla, Is Dead at 86". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 26, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ "Did King Kong inspire Nessie?". The New Zealand Herald. August 17, 2014. Retrieved January 9, 2015.

- ^ "Nessie's starring role". The Week. January 9, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

Bibliography

- American Film Institute (June 17, 2008). "AFI Crowns Top 10 Films in 10 Classic Genres". Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- Annette, Kuhn. (2007). "King Kong." In: Cook, Pam. (ed.) The Cinema Book. London: British Film Institute. P,41. and Robinson, D. (1983). "King Kong." In: Lloyd, A. (ed.) Movies of the Thirties. Orbis Publishing Ltd.

- Doherty, Thomas Patrick (1999). Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema, 1930–1934. Columbia University Press. p. 293. ISBN 0231110944.

- Eagan, Daniel (2010). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc, New York, NY p. 22. ISBN 9780826429773.

- Ebert, Roger (February 3, 2002). "King Kong Movie Review & Film Summary (1933)". RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Erb, Cynthia Marie (2009). Tracking King Kong: a Hollywood Icon in World Culture. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press. pp. 5–54. ISBN 9780814334300.

- Erish, Andrew (January 8, 2006). "Illegitimate Dad of King Kong". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 14, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- Grant, Elizabeth. (1996). "Here Comes the Bride." In Grant, Barry Keith (ed.), The Dread of Difference: Gender and the Horror Film. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Goldner, Orville and George E. Turner (1975). The Making of King Kong: The Story Behind a Film Classic. A.S. Barnes. ISBN 0498015106.

- Gottesman, Ronald and Harry Geduld, ed. (1976). The Girl in the Hairy Paw: King Kong as Myth, Movie, and Monster. Avon. ISBN 0380006103.

- Hall, Mordaunt (March 3, 1933). "King Kong". The New York Times. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- Hall, Roger L. (1997). A Guide to Film Music: Songs and Scores. PineTree Press.

- Haver, Ronald (1987). David O. Selznick's Hollywood. New York: Random House. ISBN 9780517476659.

- "King Kong Collection". Amazon UK. December 19, 2005. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- Lloyd, Ann, ed. (1983). Movies of the Thirties. UK: Orbis Publishing Ltd.

- Maltin, Leonard, ed. (2007). Leonard Maltin's 2008 Movie Guide. New York: Signet. ISBN 9780451221865.

- Morton, Ray (2005). King Kong: The History of a Movie Icon From Fay Wray to Peter Jackson. New York City: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books. ISBN 9781557836694. OCLC 61261236.

- Ollier, Claude. (May–June 1965). "Un roi à New York (A King in New York)" (Milne, Tom, trans.), in Hillier, Jim (ed.), Cahiers du Cinéma: The 1960s: New Wave, New Cinema, Reevaluating Hollywood, Harvard University Press, 1986.

- Peary, Gerald (2004). "Missing Links: The Jungle Origins of King Kong". Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- "King Kong (1933)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on December 30, 2009. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- United Press International. "Empire State Building to Dim Lights in Remembrance of Actress Fay Wray". United Press International, Inc. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

External links

- King Kong essay by Michael Price on the National Film Registry website

- King Kong essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 205-207

- List of the 400 nominated screen characters

- King Kong at IMDb

- King Kong at Box Office Mojo

- King Kong at Rotten Tomatoes

- King Kong at the TCM Movie Database

- King Kong at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films