LGBT in the Nordic countries

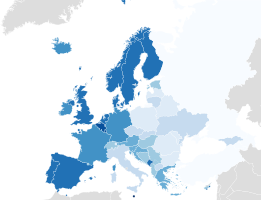

LGBTQ rights in Europe | |

|---|---|

Same-sex marriage

Civil unions

Limited domestic recognition (cohabitation)

Limited foreign recognition (residency rights)

No recognition

Constitutional limit on marriage | |

| Status | Legal, with an equal age of consent, in all 51 states Legal, with an equal age of consent, in all 6 dependencies and other territories |

| Gender identity | Legal in 39 out of 51 states Legal in 3 out of 6 dependencies and other territories |

| Military | Allowed to serve openly in 40 out of 47 states having an army Allowed in all 6 dependencies and other territories |

| Discrimination protections | Protected in 44 out of 51 states Protected in all 6 dependencies and other territories |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | Recognised in 29 out of 51 states Recognised in all 6 dependencies and other territories |

| Restrictions | Same-sex marriage constitutionally banned in 15 out of 51 states |

| Adoption | Legal in 22 out of 51 states Legal in 5 out of 6 dependencies and other territories |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) rights are widely diverse in Europe per country. 22 of the 38 countries that have legalised same-sex marriage worldwide are situated in Europe. A further 11 European countries have legalised civil unions or other forms of recognition for same-sex couples.

Several European countries do not recognise any form of same-sex unions. Marriage is defined as a union solely between a man and a woman in the constitutions of Armenia, Belarus, Bulgaria, Georgia, Lithuania, Moldova, Poland, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia and Ukraine. Of these, however, Croatia, Hungary, Latvia and Montenegro recognise same-sex partnerships. Same-sex marriage is unrecognised but not constitutionally banned in the constitutions of Albania, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Turkey, Romania and Vatican City. Eastern Europe is generally seen as having fewer legal rights and protections, worse living conditions, and less supportive public opinion for LGBT people than that in Western Europe. The situation for LGBTQ people is considered the worst in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine.

All European countries that allow marriage also allow joint adoption by same-sex couples. Of the countries that have civil unions only, none but Croatia and Liechtenstein allow joint adoption, and only Italy and San Marino allow step-parent adoption only.

In the 2011 UN General Assembly declaration for LGBT rights, state parties were given a chance to express their support, opposition or abstention on the topic. A majority of the European countries expressed their support, and only Kazakhstan expressed its opposition. State parties that expressed abstention were Azerbaijan, Belarus, Russia, and Turkey.

In December 2020, Hungary explicitly legally banned adoption for same-sex couples within its constitution,[1][2] and in June 2021 the Hungarian parliament approved a law prohibiting the showing of "any content portraying or promoting sex reassignment or homosexuality" to minors, similar to the Russian "anti-gay propaganda" law.[3] Sixteen EU member states condemned the law, calling it a breach of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.[4]

The top three European countries in terms of LGBT equality according to ILGA-Europe are Malta, Iceland and Belgium.[5][6] Western Europe is often regarded as being one of the most progressive regions in the world for LGBT people to live in.

History

Although same-sex relationships were quite common in ancient Greece, Rome and pagan Celtic societies, after Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, severe laws against homosexual behaviour appeared. An edict by the Emperor Theodosius I in 390 condemned all "passive" homosexual men to death by public burning. This was followed by the Corpus Juris Civilis of Justinian I in 529, which prescribed public castration and execution for all who committed homosexual acts, both active and passive partners. In 670, Archbishop of Canterbury Theodore of Tarsus published a Penetential prescribing penances for homosexual activity comparable to those prescribed for murder and infanticide.[7] Homosexual behaviour, called sodomy, was considered a capital crime in most European countries, and thousands of homosexual men were executed across Europe during waves of persecution in these centuries. Lesbians were less often singled out for punishment, but they also suffered persecution and execution from time to time.[8]

Since the foundation of Poland in 966, Polish law has never defined homosexuality as a crime.[9] Forty years after Poland lost its independence in 1795, the sodomy laws of Russia, Prussia, and Austria came into force in the partitioned Polish territory. Poland regained its independence in 1918 and abandoned the laws of the occupying powers.[10][11][12] In 1932, Poland codified the equal age of consent for homosexuals and heterosexuals at 15.[13]

In Turkey, homosexuality has been legal since 1858.[14][15]

During the French Revolution, the French National Assembly rewrote the criminal code in 1791, omitting all reference to homosexuality. During the Napoleonic wars, homosexuality was decriminalised in territories coming under French control, such as the Netherlands and many of the pre-unification German states; however, in Germany this ended with the unification of the country under the Prussian Kaiser, as Prussia had long punished homosexuality harshly[citation needed]. On 6 August 1942, the Vichy government made homosexual relations with anyone under twenty-one illegal as part of its conservative agenda. Most Vichy legislation was repealed after the war—but the anti-gay Vichy law remained on the books for four decades until it was finally repealed in August 1982 when the age of consent (15) was again made the same for heterosexual as well as homosexual partners.

Nevertheless, gay men and lesbians continued to live closeted lives, since moral and social disapproval by heterosexual society remained strong across Europe for another two decades, until the modern gay rights movement began in 1969.

Various countries under dictatorships in the 20th century were very anti-homosexual, such as in the Soviet Union, in Nazi Germany and in Spain under Francisco Franco's regime. In contrast, after Poland regained independence after World War I, it went on in 1932 to become the second country in 20th-century Europe to decriminalise homosexual activity (after the Soviet Union, which had decriminalized it in 1917 under the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, but re-criminalized it in 1933 under Stalin), followed by Denmark in 1933, Iceland in 1940, Switzerland in 1942 and Sweden in 1944.

In 1956, the German Democratic Republic abolished paragraph 175 of the German penal code which outlawed homosexuality.[16] In 1962, homosexual behaviour was decriminalized in Czechoslovakia, following the scientific research of Kurt Freund that included phallometry of gay men who appeared to have given up sexual relations with other men and established heterosexual marriages. Freund came to the conclusion that a homosexual orientation cannot be changed. However, the claim that phallometry on men was the only reason for the decriminalization of homosexual behaviour in Czechoslovakia is contradicted by the fact that it applied to women as well, as the notion of a male-specific fixity of sexual orientation as an argument for gay rights combined with the notion of female sexual plasticity is adverse to lesbian rights.[17][18]

Same-sex marriage, full adoption rights and:

Legal gender change, surgery not required and:

In 1972, Sweden became the first country in the world to allow people who were transgender by legislation to surgically change their sexual organs and provide free hormone replacement therapy.[19]

In 1979, a number of people in Sweden called in sick with a case of being homosexual, in protest of homosexuality being classified as an illness. This was followed by an activist occupation of the main office of the National Board of Health and Welfare. Within a few months, Sweden became the first country in Europe from those that had previously defined homosexuality as an illness to remove it as such.[20]

In 1989, Denmark was the first country in Europe, and the world, to introduce registered partnerships for same-sex couples.[21]

In 1991, Bulgaria was the first country in Europe to ban same-sex marriage.[22] Since then, thirteen countries have followed (Lithuania in 1992, Belarus and Moldova in 1994, Ukraine in 1996, Poland in 1997, Latvia and Serbia in 2006, Montenegro in 2007, Hungary in 2012, Croatia in 2013, Slovakia in 2014, Armenia in 2015 and Georgia in 2018).[22][23]

In 2001, a next step was made, when the Netherlands opened civil marriage for same-sex couples, which made it the first country in the world to do so.[24] Since then, twenty other European states have followed: Belgium in 2003,[25] Spain in 2005,[26] Norway[27] and Sweden[28] in 2009, Portugal[29] and Iceland[27] in 2010, Denmark in 2012,[25] France in 2013,[30] England and Wales in 2013, Scotland in 2014, Luxembourg[31] and Ireland in 2015,[27] Finland,[32] Malta,[33] and Germany in 2017,[34] Austria in 2019[35] Northern Ireland in 2020, Switzerland in 2022,[36] Greece[37] and Estonia in 2024.[38]

On 22 October 2009, the assembly of the Church of Sweden, voted strongly in favour of giving its blessing to homosexual couples,[39] including the use of the term marriage, ("matrimony"). The new law was introduced on 1 November 2009. Under the Danish marriage law, ministers can refuse to carry out a same-sex ceremony, but the local bishop must arrange a replacement for their church building.[40] In October 2015, the Church of Iceland voted to allow same-sex couples to marry in its churches.[41] In 2015, the Church of Norway voted to allow same-sex marriages to take place in its churches.[42] The decision was ratified at the annual conference on 11 April 2016.[43][44][45] The church formally amended its marriage liturgy on 30 January 2017, replacing references to "bride and groom" with gender-neutral text.[46] A male same-sex couple was immediately married in the church the moment the changes came into effect, on 1 February 2017.[47]

Recent developments

Civil partnerships have been legal in Ireland since 2011. In 2013, the government held a constitutional convention which voted overwhelmingly in favour of amending the constitution in order to extend marriage rights to same-sex couples. On 22 May 2015, Irish citizens voted on whether to add the following amendment to the constitution: "Marriage may be contracted in accordance with law by two persons without distinction as to their sex". 62.1% of the electorate voted in favour of the amendment, making Ireland the first country worldwide to introduce same-sex marriage through a national referendum. Ireland's first same-sex marriage ceremonies took place in November 2015.[48]

The Isle of Man has allowed civil partnerships since 2011,[49] as well as Jersey in 2012.[50] Both Crown Dependencies legalised same-sex marriage later since 22 July 2016[51] and since 1 July 2018, respectively.[52]

Liechtenstein also legalised registered partnership by 68% of voters via a referendum in 2011.[53]

On 1 January 2012, a new constitution of Hungary enacted by the government of Viktor Orbán, leader of the ruling Fidesz party, came into effect, restricting marriage to opposite-sex couples and containing no guarantees of protection from discrimination on account of sexual orientation.[54]

In 2012, the United Kingdom government launched a public same-sex marriage consultation,[55] intending to change the laws applying to England and Wales. Its Marriage Bill was signed into law on 17 July 2013. The Scottish government launched a similar consultation, aiming to legalise same-sex marriage by 2015. On 4 February 2014, the Scottish Parliament passed a bill to legalise same-sex marriages in Scotland as well as ending the "spousal veto" that would allow spouses to deny transgender partners the ability to change their legal gender.[56] Same-sex marriage was extended to Northern Ireland on 21 October 2019 and the law came into effect on 13 January 2020.

In May 2013, France legalised same-sex marriage, with French president François Hollande signing a law authorising marriage and adoption by gay couples.[57]

On 30 June 2013, Vladimir Putin, President of Russia, signed the Russian LGBT propaganda law into force, which was approved by the State Duma. The law makes distributing propaganda among minors in support of "non-traditional" sexual relationships a criminal offence.[58]

On 1 December 2013, a referendum was held in Croatia to constitutionally define marriage as a union between a woman and a man. The vote passed, with 65.87% supporting the measure, and a turnout of 37.9%.[59]

On 14 April 2014, the Parliament of Malta voted in favour of the Civil Union Act which recognises same-sex couples and permits them to adopt children. On the same day the Maltese parliament also voted in favour of a constitutional amendment to ban discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

On 4 June 2014, the Slovak parliament overwhelmingly approved a sitting social-democratic government sponsored Constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage, with 102 deputies for and 18 deputies against the legislation, fulfilling a 2/3 constitutional change requirement (minimum of 100 deputies out of 150 sitting MPs) for enacting this Constitutional amendment.[23]

On 18 June 2014, the Parliament of Luxembourg approved a bill to legalise same-sex marriage and adoption.[60] The law was published in the official gazette on 17 July and took effect 1 January 2015.[61][62][63]

On 15 July 2014, Croatian Parliament passed the Life Partnership Act giving same-sex couples all rights that married couples have, except for adoption.[64] However, the Act allows a parent's life partner to become the child's partner-guardian. Partner-guardianship as an institution similar to step-child adoption in rights and responsibilities, but it does not give parental status to the parent's life partner. Criteria for partner-guardianship and step-parent adoption for opposite-sex couples are the same. Also, regardless of partner-guardianship, a parent's life partner may attain partial parental responsibility over the child either via court or consensus among the parents and life partner, even full in some cases when the court decides that it is in the child's best interest.

In September 2014, a law went into effect in Denmark effectively dropping the former practice of requiring transgender persons to undergo arduous psychiatric evaluation and castration before being allowed legal gender change. By requiring nothing more than a statement of gender identity and subsequent confirmation of the request for gender change after a waiting period of 6 months, this means that anyone wishing their legal gender marker changed can do so with no expert-evaluation and few other formal restrictions.[65] Meanwhile, Norwegian Health Minister Bent Høie has made promises that a similar law for Norway will be drafted soon.[66] And on 18 March 2016, the Government introduced a bill to allow legal gender change without any form of psychiatric or psychological evaluation, diagnosis or any kind of medical intervention, by people aged at least 16. Minors aged between 6 and 16 also could have that possibility with parental consent.[67][68][69] The bill was approved by a vote of 79-13 by Parliament on 6 June.[70][71] It was promulgated on 17 June and took effect on 1 July 2016.[69][72]

On 9 October 2014, the Parliament of Estonia passed the Cohabitation bill by a 40–38 vote.[73] It was signed by President Toomas Hendrik Ilves that same day and took effect on 1 January 2016.[74]

On 27 November 2014 the Parliament of Andorra passed a Civil Union bill, legalising also joint adoption for same-sex partners. On 24 December 2014, the bill was published in the official journal, following promulgation by co-prince François Hollande as signature of one of the two co-princes was needed. It took effect on 25 December 2014.[75]

On 12 December 2014 the Parliament of Finland passed a same-sex marriage bill by a 101–90 vote.[76] The law was signed by President Sauli Niinistö on 20 February 2015. In order that the provisions of the framework law would be fully implementable further legislation has to be passed. The law took effect on 1 March 2017.[77]

In January 2015, the Parliament of North Macedonia voted to constitutionally define marriage as a union solely between a man and a woman.[78] On 9 January, the parliamentary committee on constitutional issues approved a series of amendments, including the aforementioned limitation of marriage and the additional requirement of a two-thirds majority for any future regulation of marriage, family and civil unions (a requirement previously reserved only for issues such as sovereignty and territorial questions). On 20 January, the amendments were approved in parliament by 72 votes to 4. However, in order for these amendments to be added to the constitution, a final vote was required. This final parliamentary session was commenced on 26 January but never concluded, as the ruling coalition did not obtain the two-thirds majority required. The parliamentary session on the constitutional amendments was in recess until the end of 2015, thus the amendment failed.[79]

On 7 February 2015, Slovaks voted in a referendum to ban same-sex marriage and same-sex parental adoption.[80] The result of the referendum was for enacting the ban proposals, with 95% and 92% votes for, respectively.[81] However, the referendum was deemed invalid under referendum law because of a low turnout (below 50% requirement).[82]

On 3 March 2015 the Parliament of Slovenia passed a same-sex marriage bill by a 51–28 vote.[83] On 20 December 2015, Slovenians rejected the new same-sex marriage bill by a margin of 63% to 37%.

In November 2015, the Parliament of Cyprus approved a bill which legalised civil unions for same-sex couples in a 39–12 vote.[84] It took effect on 9 December 2015.[85][86]

A bill to legalise civil unions for same-sex couples in Greece was approved in December 2015 by its Parliament in a 194–55 vote.[87] The law was signed by the President and took effect on 24 December 2015.[88]

On 29 April 2016, the Parliament of the Faroe Islands, a Danish dependency, voted to extend Danish same-sex marriage legislation to the territory, excluding the possibility to be legally wed in a religious ceremony. The Danish Parliament still had to approve the exclusion of religious marriages for the Faroe Islands, unlike in Denmark where churches can perform marriages between persons of the same sex.[89][90] The law within the Faroe Islands went into effect on 1 July 2017, after the ratification formality by both the Danish Parliament and royal assent.

A bill to legalise civil unions for same-sex couples in Italy was approved on 11 May 2016 by the Parliament of Italy. The law was signed by the President on 20 May 2016.[91] It was published in the Official Gazette on 21 May and therefore entered into force on 5 June 2016.[92]

On 21 September 2016, the States of Guernsey approved the bill to legalize same-sex marriage, in a 33–5 vote.[93][94] It received Royal Assent on 14 December 2016. The law went into effect on 1 July 2017.

On 26 October 2016, the Gibraltar Parliament unanimously approved a bill to allow same-sex marriage by a vote of 15–0. It received Royal Assent 1 November 2016.[95] The law went into effect on 15 December 2016.

On 31 January 2017, the Supreme Court of Cassation in Italy refused, on procedural grounds, to rescind a lower judgment recognising a marriage between two French women (one of these had the right to claim Italian citizenship iure sanguinis), officiated in the French region of Nord-Pas-de-Calais. This is the first time a same-sex marriage is admitted in Italy, but the judgment does not imply that this will necessarily be the case in general terms.[96]

Within July 2017, both the Parliaments of Germany and Malta approved bills to allow same-sex marriage. The Presidents of both countries signed the bills into law. The same-sex marriage laws within Malta went into effect on 1 September 2017 and the same-sex marriage laws within Germany went into effect on 1 October 2017.[98][99]

In October 2017, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted the first intersex-specific resolution of its kind from a European intergovernmental institution, after 33 members voted in favour. The resolution called for intersex peoples right to bodily autonomy and physical integrity by calling for prohibition of "medically unnecessary sex-"normalising" surgery, sterilisation and other treatments practised on intersex children without their informed consent" It recommends the committee of ministers to bring the resolution to the attention of their governments, the need for increased psychosocial support, and calls for policymakers to "ensure that anti-discrimination legislation effectively applies to and protects intersex people."[100][101]

On 5 December 2017, the Constitutional Court of Austria struck down the ban on same-sex marriage as unconstitutional. Same-sex marriage became legal on 1 January 2019.[102][103]

In late 2018 San Marino parliament voted to legalise civil unions with stepchild adoption rights.[104] The law to permit civil unions became fully operational on 11 February 2019, following a number of further legal and administrative changes.

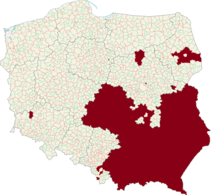

On 18 December 2019, the European Parliament voted, 463 to 107, to condemn the more than 80 LGBT-free zones in Poland.[105][106]

On 26 September 2021, nearly two thirds of Swiss voters agreed to legalise civil marriage and the right to adopt children for same-sex couples in an optional referendum,[107][108] after the National Council and the Council of States had both approved the aforementioned legalisations on 18 December 2020. The new law has taken effect on 1 July 2022.[109][110][111][112]

On 20 June 2023, the Parliament of Estonia approved a bill to allow same-sex marriage by a vote of 55–34. It took effect on 1 January 2024.[113]

On 15 February 2024 the Greek Parliament voted in favour of legalizing same-sex marriage by a margin of 176-76. [114]

Since July 1, 2024 Latvia implemented a registered partnership law that has the same rights and obligations as married couples - with the exception of the title of marriage, any adoption or inheritance rights and obligations.[115]

Public opinion around Europe

| Eurobarometer 2023: % of people in each country who agree with the statement that "Gay, lesbian and bisexual people should have the same rights as heterosexual people (marriage, adoption, parental rights)."[116] | |

| Country | Percentage |

|---|---|

| 95% | |

| 94% | |

| 92% | |

| 87% | |

| 84% | |

| 81% | |

| 81% | |

| 79% | |

| 78% | |

| 77% | |

| 75% | |

| 69% | |

| 68% | |

| 63% | |

| 59% | |

| 54% | |

| 45% | |

| 44% | |

| 44% | |

| 42% | |

| 41% | |

| 39% | |

| 37% | |

| 35% | |

| 35% | |

| 29% | |

| 27% | |

| 21% | |

In a 2002 Pew Global Attitudes Project surveyed by the Pew Research Center, showed majorities in every Western European nation said homosexuality should be accepted by society, while most Russians, Poles and Ukrainians disagreed.[117] According to pollster Gallup Europe in 2003, women, younger generations, and the highly educated are more likely to support same-sex marriage and adoption rights for gay people than other demographics.[118]

A Eurobarometer in 2006 surveying up to 30,000 people from each European Union country, showed split opinion around the then 27 member states on the issue of same-sex marriage. The majority of support came from the Netherlands (82%), Sweden (71%), Denmark (69%), Belgium (62%), Luxembourg (58%), Spain (56%), Finland (54%), Germany (52%) and the Czech Republic (52%). All other countries within the EU had below 50% support; with Romania (11%), Latvia (12%), Cyprus (14%), Bulgaria (15%), Greece (15%), Lithuania (17%), Poland (17%), Hungary (18%) and Malta (18%) at the other end of the list.[119] Same-sex adoption had majority support from only two countries: Netherlands at 69% and Sweden at 51% and the least support from Poland and Malta on 7%, respectively.[119]

A more recent survey carried out in October 2008 by The Observer affirmed that a small majority of Britons—55%—support same-sex marriage.[120] A 2013 poll shows that the majority of the Irish public support same-sex marriage and adoption, 73% and 60%, respectively.[121] France has support for same-sex marriage at 62%,[122] while support among Russians stands at 14%.[123] Italy has support for the 'Civil Partnership Law' between people of the same gender at 45% with 47% opposed.[124] In 2009 58.9% of Italians supported civil unions, while a 40.4% minority supported same-sex marriage.[125] In 2010, 63.9% of Greeks supported same-sex partnerships, while a 38.5% minority supported same-sex marriage.[126] In 2012 a poll by MaltaToday[127] showed that 41% of Maltese supported same-sex marriage, with support increasing to 60% amongst the 18–35 age group. In a 2013 opinion poll conducted by CBOS, 65% of Poles were against same-sex civil unions, 72% of Poles were against same-sex marriage, 88% were against adoption by same-sex couples, and 68% were against lesbian, gay, or bisexual people publicly showing their way of life.[128] In Croatia, a poll from November 2013 revealed that 59% of Croats think that marriage should be constitutionally defined as a union between a man and a woman, while 31% do not agree with the idea.[129] A CBOS opinion poll from February 2014 found that 70% of Poles believe same-sex sexual activity is morally unacceptable, while only 22% believed it is morally acceptable.[130]

Public support for same-sex marriage from EU member states as measured from a 2015 poll is the greatest in the Netherlands (91%), Sweden (90%), Denmark (87%), Spain (84%), Ireland (80%), Belgium (77%), Luxembourg (75%), the United Kingdom (71%) and France (71%).[131] In recent years, support has risen most significantly in Malta, from 18% in 2006 to 65% in 2015 and in Ireland from 41% in 2006 to 80% in 2015.[132]

After the approval of same-sex marriage in Portugal in January 2010, 52% of the Portuguese population stated that they were in favor of the legislation.[133] In 2008, 58% of the Norwegian voters supported same-sex marriage, which was introduced in the same year, and 31 percent were against it.[134] In January 2013, 54.1% of Italians respondents supported same-sex marriage.[135] In a late January 2013 survey, 77.2% of Italians respondents supported the recognition of same-sex unions.[136]

In Greece support more than tripled between 2006 and 2017. In 2006 15% responded that they agreed with same-sex marriages being allowed throughout Europe.[132] In 2017 according to a survey 50.04% of Greeks agreed with gay marriage. A more recent survey in 2020 showed that 56% of the Greek population accept gay marriage.[137][138]

In Ireland, a 2008 survey revealed 84% of people supported civil unions for same-sex couples (and 58% for same-sex marriage),[139] while a 2010 survey showed 67% supported same-sex marriage[140] by 2012 this figure had risen to 73% in support.[141] On 22 May 2015, 62.1% of the electorate voted to enshrine same-sex marriage in the Irish constitution as equal to heterosexual marriage.

A March 2013 survey by Taloustutkimus found that 58% of Finns supported same-sex marriage.[142]

In Croatia, a poll conducted in November 2013 revealed that 59% of Croats think that marriage should be constitutionally defined as a union between a man and a woman, while 31% do not agree with the idea.[143]

In Poland a 2013 public poll revealed that 70% of Poles reject the idea of registered partnerships.[144] Another survey in February 2013 revealed that 55% were against and 38% of Poles support the idea of registered partnerships for same-sex couples.[145]

In the European Union, support tends to be the lowest in Bulgaria, Latvia, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, and Lithuania. The average percentage of support for same-sex marriage in the European Union as of 2006 when it had 25 members was 44%, which had descended from a previous percentage of 53%. The change was caused by more socially conservative nations joining the EU.[132] In 2015, with 28 members, average support was at 61%.[131]

A 2015 NDI public opinion poll shows that only 10% of the population in the Balkans (Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania, Kosovo, Montenegro and North Macedonia) believe LGBTI marriages are acceptable, in contrast to 88% who think they're unacceptable.[146]

Adoption

| Country | Pollster | Year | For | Against | Don't Know/Neutral/No answer/Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 65%[147] | 30% | 5% | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 72%[148] | 21% | 7% | |

| Eurobarometer | 2006 | 12%[149] | 68%[149] | 20%[149] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2006 | 10%[149] | 86%[149] | 4%[149] | |

| CVVM | 2019 | 47%[150] | 47% | 6% | |

| Pew Research Center | 2017 | 75%[151] | - | - | |

| HumanrightsEE | 2023 | 47%[152] | 44%[152] | 9%[152] | |

| Taloustutkimus | 2013 | 51%[153] | 42%[153] | 7%[153] | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 62%[148] | 29% | 10% | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 69%[148] | 24% | 6% | |

| KAPA Research | 2023 | 53%[154] | 41%[154] | 6%[154] | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 59%[148] | 36% | 5% | |

| Red C Poll | 2011 | 60%[155] | - | - | |

| Eurispes | 2023 | 50.4% [156] | 49.6% | 0% | |

| SKDS | 2023 | 27%[157] | 23%[157] | 46%[157] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2006 | 12%[149] | 82%[149] | 6%[149] | |

| Politmonitor | 2013 | 55%[158] | 44%[158] | 1%[158] | |

| Misco | 2014 | 20%[159] | 80%[159] | - | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 83%[148] | 12% | 5% | |

| YouGov | 2012 | 54%[160] | 34%[160] | 12%[160] | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 33%[148] | 58% | 10% | |

| Pew Research Center | 2017 | 59%[161] | 28%[161] | 13%[161] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2006 | 8%[149] | 82%[149] | 10%[149] | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 23%[148] | 67% | 10% | |

| Civil Rights Defenders | 2020 | 22.5%[162] | - | - | |

| Eurobarometer | 2006 | 12%[149] | 84%[149] | 4%[149] | |

| Delo Stik | 2015 | 38%[163] | 55%[163] | 7%[163] | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 77%[148] | 17% | 6% | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 79%[148] | 17% | 4% | |

| Pink Cross | 2020 | 67%[164] | 30%[164] | 3%[164] | |

| Gay Alliance of Ukraine | 2013 | 7%[165] | 68%[165] | 12% 13% would allow some exceptions[165] | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 72%[148] | 19% | 9% |

Legislation by country or territory

European Union

| LGBT rights in: | Same-sex sexual activity | Recognition of same-sex unions | Same-sex marriage | Adoption by same-sex couples | LGB people allowed to serve openly in military | Anti-discrimination laws concerning sexual orientation | Laws concerning gender identity/expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

joint adoption legal in 17/27 member states |

4/27 states ban some anti-gay discrimination. 23/27 states ban all anti-gay discrimination |

Central Europe

| LGBT rights in: | Same-sex sexual activity | Recognition of same-sex unions | Same-sex marriage | Adoption by same-sex couples | LGB people allowed to serve openly in military | Anti-discrimination laws concerning sexual orientation | Laws concerning gender identity/expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

+ UN decl. sign. |

joint adoption since 2016[171][172][173] |

||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

Legal in West Germany since 1969; equal age of consent since 1988 in East Germany and since 1994 in unified Germany + UN decl. sign.[168][180] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

| ||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

joint adoption since 2023[200][201] |

Has no military | |||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

registered partnership proposed 2019 |

||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

Limited residency rights for married same-sex couples since 2018 (Proposed) |

||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

Registered partnerships since 2017[216] |

joint adoption since 2022[218] |

|||||

Legal in the cantons of Geneva (as part of France), Ticino, Valais, and Vaud since 1798; equal age of consent since 1990 + UN decl. sign.[168][220] |

Nationwide since 2007[224] |

joint adoption since 2022[109][225] |

Eastern Europe

| LGBT rights in: | Same-sex sexual activity | Recognition of same-sex unions | Same-sex marriage | Adoption by same-sex couples | LGB people allowed to serve openly in military | Anti-discrimination laws concerning sexual orientation | Laws concerning gender identity/expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(Disputed territory) |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

Female always legal[238][168] |

|||||||

(Disputed territory) |

|||||||

(Disputed territory) |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

Northern Europe

| LGBT rights in: | Same-sex sexual activity | Recognition of same-sex unions | Same-sex marriage | Adoption by same-sex couples | LGBT people allowed to serve openly in military | Anti-discrimination laws concerning sexual orientation | Laws concerning gender identity/expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

joint adoption since 2010[251][252] |

||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

joint adoption since 2024[257] |

||||||

(Autonomous Territory within the Kingdom of Denmark) |

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

joint adoption since 2017 |

||||||

(As part of Denmark) + UN decl. sign.[168] |

Registered partnerships from 1996 to 2010 (existing partnerships are still recognised)[269] |

No standing army | |||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

joint adoption since 2009[293][294] |

||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

Southern Europe

| LGBT rights in: | Same-sex sexual activity | Recognition of same-sex unions | Same-sex marriage | Adoption by same-sex couples | LGBT people allowed to serve openly in military | Anti-discrimination laws concerning sexual orientation | Laws concerning gender identity/expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(Overseas Territory of the United Kingdom) |

+ UN decl. sign.[168][304][305] |

||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

Has no military | ||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

| ||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

Gender change not legal. | ||||||

(Overseas Territory of the United Kingdom) |

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

(Disputed territory) |

(as part of Yugoslavia); equal age of consent since 2004[168] |

| |||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

Pathologization or attempted treatment of sexual orientation by mental health professionals illegal since 2016 |

||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

Gender change is legally recognized since 2021[352] | ||||||

(Disputed territory) |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

Pathologization or attempted treatment of sexual orientation by mental health professionals illegal nationwide since 2023.[384] |

||||||

| Has no military |

Western Europe

| LGBT rights in: | Same-sex sexual activity | Recognition of same-sex unions | Same-sex marriage | Adoption by same-sex couples | LGB people allowed to serve openly in military | Anti-discrimination laws concerning sexual orientation | Laws concerning gender identity/expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

Legal in Savoy since 1792; equal age of consent since 1982 + UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

(Crown Dependency of the United Kingdom) |

+ UN decl. sign.[400][401][168] |

[406] |

|||||

Female always legal + UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

(Crown Dependency of the United Kingdom) |

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

||||||

(Crown Dependency of the United Kingdom) |

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

|||||||

+ UN decl. sign.[168] |

Rating of countries from ILGA-Europe

The ILGA rating illustrates the legal and policy situation of LGBT people in countries. Data for May 2024. Source: ILGA-Europe[457]

| Country or territory | Rating, % |

|---|---|

| 87.84 | |

| 83.02 | |

| 78.47 | |

| 76.41 | |

| 76.35 | |

| 70.78 | |

| 70.78 | |

| 70.04 | |

| 69.53 | |

| 67.14 | |

| 66.13 | |

| 64.38 | |

| 62.31 | |

| 58.95 | |

| 57.17 | |

| 51.88 | |

| 50.35 | |

| 50.07 | |

| 49.97 | |

| 49.63 | |

| 48.21 | |

| 46.14 | |

| 43.23 | |

| 40.25 | |

| 39.34 | |

| 36.38 | |

| 35.96 | |

| 35.75 | |

| 34.62 | |

| 32.53 | |

| 30.63 | |

| 30.50 | |

| 29.51 | |

| 28.44 | |

| 27.61 | |

| 25.41 | |

| 25.30 | |

| 23.97 | |

| 23.22 | |

| 18.86 | |

| 18.76 | |

| 17.50 | |

| 14.52 | |

| 13.93 | |

| 11.16 | |

| 9.16 | |

| 4.75 | |

| 2.25 | |

| 2.00 |

See also

- Recognition of same-sex unions in Europe

- LGBTQ rights in the European Union

- Same-sex adoption in Europe

- ILGA-Europe

- Ages of consent in Europe

- LGBTQ rights by country or territory

- LGBTQ rights in Asia

- LGBTQ rights in Africa

- LGBTQ rights in Oceania

- LGBTQ rights in the Americas

- Transgender Europe

- Gayrope

Notes

References

- ^ "Hungary Amends Constitution to Redefine Family, Effectively Banning Gay Adoption". NBC News. Reuters. 15 December 2020. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Tracy, Matt (17 December 2020). "Hungary Bans LGBTQ Adoption Rights in Broad Power Grab". Gay City News. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "Hungary's parliament passes anti-LGBT law ahead of 2022 election". CNN. 15 June 2021. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ "Thirteen EU countries denounce Hungary's new anti-LGBT law". EuroNews. 22 June 2021. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ "Malta ranks first in European 'rainbow map' of LGBTIQ rights". MaltaToday.com.mt. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023.

- ^ "2024 RAINBOW MAP". ILGA-Europe. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "Theodore of Tarsus – LGBT History UK". Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Crompton, Louis. (2003). Homosexuality & Civilization. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 1–212.

- ^ Sierzpowska-Ketner, Anna. "Poland". Archived from the original on 29 July 2010. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ^ "A Brief History of Gay Poland". Globalgayz.com. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ "Poland". glbtq. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ "The International Encyclopedia of Sexuality: Poland". .hu-berlin.de. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ Krieger, Joel (2001). The Oxford companion to politics of. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-19-511739-4.

- ^ Kazi, Tehmina (7 October 2011). "The Ottoman empire's secular history undermines sharia claims". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ Cunningham, Erin (24 June 2016). "In Turkey, it's not a crime to be gay. But LGBT activists see a rising threat". The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ Green, J. and De La Motte, B. (2015) "Stasi State or Socialist Paradise?: The German Democratic Republic and What Became of It." p.74

- ^ Gay and Lesbian Rights: A Reference Handbook, 2nd Edition, David E Newton

- ^ Before Stonewall: Activists for Gay and Lesbian Rights in Historical Context, Vern L. Bullough 2002

- ^ Hanna Jedvik (5 March 2007). "Lagen om könsbyte ska utredas". RFSU. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 24 June 2007.

- ^ Jag känner mig lite homosexuell idag | quistbergh.se The American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders in 1973 with publication of its DSM II. Source: The American Psychiatric Association, and DSM II. Thus, the American Psychiatric Association took this step six years before a similar action was taken in Sweden.

- ^ 103982@au.dk (13 April 2018). "Vis". danmarkshistorien.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 2 June 2018.

{cite web}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "European countries which define marriage as a union between a man and a woman in their constitutions". ILGA Europe. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ a b Radoslav, Tomek (4 June 2014). "Slovak Lawmakers Approve Constitutional Ban on Same-Sex Marriage". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ "Same-Sex Dutch Couples Gain Marriage and Adoption Rights". The New York Times. Reuters. 20 December 2000. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ a b Taylor, Adam (26 June 2015). "What was the first country to legalize gay marriage?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ McLean, Renwick (1 July 2005). "Spain Legalizes Gay Marriage; Law Is Among the Most Liberal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 1 November 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ a b c Navarre, Brianna; Trimble, Megan (16 December 2021). "Same-Sex Marriage Legalization by Country". U.S. News. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ "Sweden: Same-Sex Marriage Now Legal". The New York Times. Associated Press. 2 April 2009. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "Portugal passes legal gender change law". BBC News. 13 April 2018. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "France marks five-year anniversary of same-sex marriage". France 24. 23 April 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "In Luxembourg, gay premier marries, in first for EU". Reuters. 15 May 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ Lavers, Michael K. (21 February 2015). "Finnish president signs same-sex marriage bill". Washington Blade. Archived from the original on 23 September 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "Maltese Parliament Legalizes Same-Sex Marriage". U.S. News. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "Germany Legalizes Same-Sex Marriage After Merkel U-Turn". U.S. News. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "Austrian women celebrate country's first same-sex marriage". Yahoo!. Associated Press. 1 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ "Swiss approve same-sex marriage by wide margin in referendum". AP NEWS. 26 September 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Greek parliament approves legalisation of same-sex civil marriage". euronews. 15 February 2024. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ "Same-sex marriage now legal in Estonia". Eesti Rahvusringhääling. January 2024. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- ^ "Kyrkomötet öppnade för enkönade äktenskap". Dagens Nyheter. Archived from the original on 23 October 2009. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ Orange, Richard (7 June 2012). "Gay Danish couples win right to marry in church". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Underwood, York (29 October 2015). "Icelandic Priests Cannot Deny Gay Marriage". The Reykjavík Grapevine. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ Wee, Darren (2 November 2015). "Norway bishops open doors to gay church weddings". Gay Star News. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ Pettersen, Jørgen; Edvardsen, Ingvild; Skjærseth, Lars Erik (11 April 2016). "Nå kan homofile gifte seg i kirka". NRK. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Oesterud, Tor Ingar (11 April 2016). "Large majority want gay marriage in church". Norway Today. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Fouche, Gwladys (11 April 2016). "Norway's Lutheran church votes in favor of same-sex marriage". Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Fouche, Gwladys (30 January 2017). "Norway's Lutheran Church embraces same-sex marriage". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ Hadland, Lisa S. (1 February 2017). "First gay couple wed". Norway Today. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ "Same-sex couples can marry from today". RTÉ News. 16 November 2015. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021.

- ^ "First heterosexual civil partnership". BBC News. 14 October 2016. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "Jersey recognises civil partners". BBC News. 13 January 2012. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "Same-sex couples can now marry in the Isle of Man". ITV Granada. 22 July 2016. Archived from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ "Jersey to introduce same-sex marriage from 1 July". BBC News. 27 June 2018. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ "Liechtenstein: Homo-Ehe kommt nächstes Jahr". Queer.de. 17 December 2009. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ "New Hungarian constitution comes into effect with same-sex marriage ban". Pinknews. Archived from the original on 14 February 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ "Gay marriage: Government consultation begins". BBC News. 15 March 2012. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023.

- ^ "Scotland Establishes Marriage Equality". the Advocate. 4 February 2014.

- ^ "French President Signs Gay Marriage into Law". HuffPost. 18 May 2013.

- ^ "HRW Slams Effects of Russia's Gay 'Propaganda' Law, One Year On". RFE/RL. 1 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "2013 Referendum". Izbori.hr. Archived from the original on 20 January 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Feu vert pour le mariage gay au Luxembourg". Chamber of Deputies (Luxembourg). 18 June 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ^ "Mémorial A n° 125 de 2014" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Same-sex marriages from January 1". Wort.lu. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Same-Sex Marriage in Luxembourg from 1 January 2015". Chronicle.lu. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Povijesna odluka: Hrvatska ima Zakon o životnom partnerstvu". tportal.hr. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Denmark Drops Forced Sterilization of Transgender People". Human Rights Campaign. 11 June 2014. Archived from the original on 17 April 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ "— En stor dag!". BLIKK Magasin. 10 April 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ "Norway set to allow gender change without medical intervention". Yahoo! News.

- ^ Services, Ministry of Health and Care (18 March 2016). "Easier to change legal gender". Government.no.

- ^ a b "Lov om endring av juridisk kjønn". Stortinget. 29 March 2016.

- ^ "Norway now allows trans people to decide their own gender". 6 June 2016.

- ^ Morgan, Joe (6 June 2016). "Norway becomes fourth country in the world to allow trans people to determine their own gender". Gay Star News. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Lov om endring av juridisk kjønn – Lovdata". lovdata.no.

- ^ "Parliament Passes Cohabitation Act; President Proclaims It". News – ERR. 9 October 2014. Archived from the original on 30 November 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Riigikogu". Riigikogu.

- ^ RTVA, Andorra Difusió. "Demà entren en vigor lleis importants, com la d'unions civils o la 'regla d´or' | Andorra Difusió". andorradifusio.ad.

- ^ "Eduskunnan etusivu". Web.eduskunta.fi. Archived from the original on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "President signs gender-neutral marriage law". Yle Uutiset. 20 February 2015.

- ^ Lavers, Michael K. (21 January 2015). "Macedonian lawmakers approve same-sex marriage ban". Washington Blade. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ "MACEDONIA | LGBTI Equal Rights Association for Western Balkans and Turkey". lgbti-era.org.

- ^ "Slovakia to Hold Referendum on Same-Sex Marriage". ABC News. 27 November 2014. Archived from the original on 9 December 2014.

- ^ "Slovakia's Anti-Gay Rights Referendum Flops Due To Low Turnout". HuffPost. 8 February 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Slovakia: Referendum to further limit gay rights ruled invalid". Euronews. 8 February 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Changes to the Marriage Act confirmed, homosexual couples can now marry". Rtvslo.si. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "House passes historic civil partnerships bill (Update)". Cyprus-mail.com. 26 November 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Gay νέα και ειδήσεις: Τέθηκε σε ισχύ η πολιτική συμβίωση στην Κύπρο - Antivirus Magazine". Avmag.gr. 11 December 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Civil Unions Bill in effect". In-cyprus.com. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Same-sex couples will have equal rights with heterosexual couples with cohabitation agreements". Grreporter.info. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "ΝΟΜΟΣ ΥΠ' ΑΡΙΘ. 3456 Σύμφωνο συμβίωσης, άσκηση δικαιωμάτων, ποινικές και άλλες διατάξεις". Et.gr. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Danir fara at eftirlíka ynskinum úr Føroyum". in.fo (in Faroese). Archived from the original on 7 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ "Faroe Islands Say Yes to Same-Sex Marriage". Lgbt.fo. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "Unioni Civili: Mattarella firma la legge". Ansa (in Italian). 20 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ "Legge 20 maggio 2016, n. 76. Regolamentazione delle unioni civili tra persone dello stesso sesso e disciplina delle convivenze". Gazzetta ufficiale (in Italian). Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ "This Tiny Island Has Just Voted To Introduce Same-Sex Marriage". Buzzfeed.com. 21 September 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Guernsey passes same-sex marriage law". Pinknews.co.uk. 21 September 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Gibraltar unanimously legalizes marriage equality". Sdgln.com. 26 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ territory, West – welfare, society and. "Italian Court recognizes gay marriage officiated abroad for the first time". West-info.eu. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

{cite web}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Polish president revives attacks on LGBT community in re-election campaign". The Irish Times. 12 June 2020.

- ^ "Germany votes to legalise same-sex marriage". News.com.au. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Malta legalises same-sex marriage". News.com.au. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Intersex resolution adopted by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe". OII Europe. 13 October 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "The Council of Europe makes history with its first specific resolution on the rights of intersex people | ILGA-Europe". ilga-europe.org. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "Gay marriage in Austria approved by Constitutional Court". Deutsche Welle. 5 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ Agerholm, Harriet (5 December 2017). "Austria court legalises same-sex marriage from start of 2019, ruling all existing laws discriminatory". The Independent. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "LEGGE 20 novembre 2018 n.147 – Regolamentazione delle unioni civili – Consiglio Grande e Generale".

- ^ "European Parliament slams 'LGBTI-free' zones in Poland". Deutsche Welle. 18 December 2019.

- ^ Hume, Tim (19 December 2019). "More Than 80 Polish Towns Have Declared Themselves 'LGBTQ-Free Zones'". Vice News.

- ^ "'Marriage for all' wins thumping approval of Swiss voters". Swissinfo. 26 September 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ "Switzerland same-sex marriage: Two-thirds of voters back yes". BBC News. 26 September 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ^ a b c "Voters have last word on 'marriage for all' bill". SWI swissinfo.ch. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ "Vote final" (PDF). Federal Assembly (in German and French). 18 December 2020.

- ^ "Vote final" (PDF). Federal Assembly (in German and French). 18 December 2020.

- ^ Brezar, Aleksandar; de Lagausie, Xavier (1 July 2022). "Same-sex marriage just became legal in Switzerland. This couple were among first to benefit". euronews. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "Ajalooline otsus: Eesti seadustas samasooliste abielu". ERR News (in Estonian). 20 June 2023. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ "Greece legalises same-sex marriage". BBC News. 15 February 2024. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Eurobarometer on Discrimination 2023: Discrimination in the European Union". European Commission. December 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ "Views of a Changing World 2003". The Pew Research Center. 3 June 2003. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- ^ "Public opinion and same-sex unions (2003)". ILGA Europe. Archived from the original on 8 February 2007. Retrieved 29 January 2006.

- ^ a b "Eight EU Countries Back Same-Sex Marriage". Angus Reid Global Monitor : Polls & Research. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 29 January 2006.

- ^ "Sex uncovered poll: Homosexuality". The Guardian. London. 26 October 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ "Poll: Three-Quarters in Favour of Gay Marriage". GCN. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ "Poll shows 63 percent of French back gay marriage". Reuters. 26 January 2013. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ "Same-Sex Marriage Nixed By Russians". Angus Reid Global Monitor : Polls & Research. Retrieved 29 January 2006.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Italians Divided Over Civil Partnership Law". Angus Reid Global Monitor : Polls & Research. Archived from the original on 5 May 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2007.

- ^ "Italiani più avanti della politica | Arcigay". Arcigay.it. 22 February 1999. Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ "Image". images.tanea.gr. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ "Heartening change in attitudes to put gay unions on political agenda". MaltaToday.com.mt. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ Feliksiak, Michał (February 2013). "Stosunek do praw gejów i lesbijek oraz związków partnerskich" (PDF). Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ^ "Anketa za HRT: 59 posto građana ZA promjenu Ustava > Slobodna Dalmacija > Hrvatska". Slobodnadalmacija.hr. 15 March 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ Rafał Boguszewski (February 2014). "RELIGIJNOŚĆ A ZASADY MORALNE" (PDF) (in Polish). CBOS. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ a b "Special Eurobarometer 437: Discrimination in the EU in 2015" (PDF). European Commission. October 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ a b c "EU Public Opinion: SSM" (PDF). Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ "New England's largest GLBT newspaper". Bay Windows. 25 January 2010. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ AVJonathan Tisdall. "Support for gay marriage". Aftenposten.no. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ "Italiani favorevoli ai matrimoni tra coppie omosessuali". Archived from the original on 2 March 2014.

- ^ "Rapporto Italia 2013". Eurispes (in Italian). 20 January 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Georgakopulos, Thodoris (April 2017). "What Greeks Believe in 2017". dianeosis. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ "Liberalism in Greece today: Do we live in a liberal country?" (PDF). Kana Research. October 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ "Increased support for gay marriage – Survey". BreakingNews.ie. 31 March 2008. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ "Yes to gay marriage and premarital sex: a nation strips off its conservative values". The Irish Times. 9 September 2010. Archived from the original on 19 November 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ "Poll finds Irish support for gay marriage at 73%". PinkNews. 23 February 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Poll: Over half of Finns favour same-sex marriage law". Yle Uutiset. 9 March 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Anketa za HRT: 59 posto građana ZA promjenu Ustava" (in Croatian). Slobodnadalmacija.hr. 29 November 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ "Polacy: Związki partnerskie? Niepotrzebne! [SONDAŻ TOK FM]". Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). 1 February 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ "Sondaż: Polacy przeciwko związkom partnerskim. Palikot: jest lepiej niż było". Wprost. 16 February 2013.

- ^ "NDI Public Opinion Poll in the Balkans on LGBTI Communities". NDIdemocracy. June–July 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "Discrimination in the European Union". europa.eu.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "LGBT+ Pride 2021 Global Survey" (PDF). Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "EUROBAROMETER 66 FIRST RESULTS" (PDF). TNS. European Commission. December 2006. p. 80. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ "Průzkum 2019: Čím dál více lidí si uvědomuje, že mají v rodině a mezi přáteli gaye a lesby" [Survey 2019: More and more people realize that they have gays and lesbians in their family and among friends]. nakluky.cz (in Czech). 6 July 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ Gianni Balduzzi (23 July 2018). "Sondaggi politici, italiani tra i più contrari in Europa alle adozioni gay" [Political polls find Italians among the most against gay adoptions in Europe]. Termometro Politico (in Italian). Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ a b c "Avaliku arvamuse uuring LGBT teemadel (2023)" (PDF).

- ^ a b c "Extranet - Taloustutkimus Oy".

- ^ a b c "Nearly 55% of Greeks support gay marriage and 53% adoption, poll finds". ekathimerini.com. 16 January 2024.

- ^ "Nearly three quarters of Irish people in favour of gay marriage". Thejournal.ie.

- ^ "Rapporto Italia 2023" [Italy Report 2023] (in Italian). EURISPES Istituto di Studi Politici Economici e Sociali. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ a b c "Teju trešdaļai Latvijas iedzīvotāju atbalstoša attieksme pret LGBTQ, liecina aptauja (2023)".

- ^ a b c "Politmonitor: Breite Mehrheit für Homo-Ehe". Politmonitor. Luxemburger Wort. 10 March 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ a b Sansone, Kurt (12 January 2014). "Survey – 80 per cent against gay adoption". Times of Malta. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ a b c "Le mariage et l'adoption pour tous, un an après" (PDF). YouGov. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ a b c "Pew Research Center".

- ^ "Attitudes towards LGBTI+ rights and issues in Serbia" (PDF). Civil Rights Defenders. 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ^ a b c "Večina podpira istospolne poroke, do posvojitev je zadržana".

- ^ a b c "Neue Umfrage zeigt: Klare Zustimmung für tatsächliche Gleichstellung" [New survey shows: Clear agreement for real equality] (in German). 10 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ a b c ""Гей-альянс Украина" публикует результаты исследования общественного мнения о восприятии ЛГБТ в украинском социуме".

- ^ "Perspective: what has the EU done for LGBT rights?". Café Babel. 17 May 2010. Archived from the original on 19 May 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ "What is the current legal situation in the EU?". ILGA Europe. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh "State Sponsored Homophobia 2016: A world survey of sexual orientation laws: criminalisation, protection and recognition" (PDF). International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. 17 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "RIS – Eingetragene Partnerschaft-Gesetz – Bundesrecht konsolidiert, Fassung vom 17.08.2019". www.ris.bka.gv.at.

- ^ "Unterscheidung zwischen Ehe und eingetragener Partnerschaft verletzt Diskriminierungsverbot". Constitutional Court of Austria (in German). 5 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "Bundesgesetz, mit dem das Allgemeine Bürgerliche Gesetzbuch und das Bundesgesetz über die eingetragene Partnerschaft geändert wird" (PDF). parlament.gv.at (in German).

- ^ "Entschließungsantrag betreffend der Aufhebung des Adoptionsverbots für Homosexuelle" (PDF). parlament.gv.at.

- ^ "§ 144(2) ABGB (General Civil Code)". www.ris.bka.gv.at (in German).

- ^ Sweijs, Tim. "LGBT Military Personnel: a Strategic Vision for Inclusion". hcss.nl. The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac "ILGA-Europe" (PDF). ilga-europe.org.

- ^ a b c d "Map shows how Europe forces trans people to be sterilized". Gay Star News.

- ^ "Portál veřejné správy". portal.gov.cz.

- ^ Sweijs, Tim. "LGBT Military Personnel: a Strategic Vision for Inclusion". hcss.nl. The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Trans Rights Europe Map, 2018" (PDF). Transgender Europe. 21 April 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ "glbtq >> social sciences >> Berlin" (PDF). glbtq.com.

- ^ "LPartG – nichtamtliches Inhaltsverzeichnis". www.gesetze-im-internet.de.

- ^ "Gesetz zur Einführung des Rechts auf Eheschließung für Personen gleichen Geschlechts – 2. Ergänzung der Anwendungshinweise zur Umsetzung des vorgenannten Gesetzes".

- ^ a b Connolly, Kate (30 June 2017). "German Parliament votes to legalise same-sex marriage". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ Sweijs, Tim. "LGBT Military Personnel: a Strategic Vision for Inclusion". hcss.nl. The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ "Antidiskriminierungsstelle – Publikationen – AGG in englischer Sprache". antidiskriminierungsstelle.de.

- ^ Kft, Wolters Kluwer Hungary. "2009. évi XXIX. törvény a bejegyzett élettársi kapcsolatról, az ezzel összefüggő, valamint az élettársi viszony igazolásának megkönnyítéséhez szükséges egyes törvények módosításáról – Hatályos Jogszabályok Gyűjteménye". net.jogtar.hu.

- ^ "Folyamatban levő törvényjavaslatok – Országgyűlés". www.parlament.hu.

- ^ a b "Melegházasságról szóló törvényjavaslat landolt a magyar parlamentben" (in Hungarian). Index.hu. 29 June 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Fundamental Law of Hungary" (PDF). TASZ. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Gorondi, Pablo (18 April 2011). "Hungary passes new conservative constitution". Reading Eagle. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ "Hungary amends constitution to redefine family, effectively banning gay adoption". ABC News. 15 December 2020. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ Wareham, Jamie (19 May 2020). "Transgender People In Hungary Lose Right To Gender Recognition". Forbes. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Gesetz über die eingetragene Partnerschaft gleichgeschlechtlicher Paare (Partnerschaftsgesetz; PartG)" (PDF). gesetze.li (in German).

- ^ Sele, David (16 May 2024). "Landtag beschließt Ehe für alle". Vaterland (in German). Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ "Einladung - Öffentliche Landtagssitzung (Mittwoch/Donnerstag/Freitag, 6./7./8. März 2024 09.00 Uhr, Landtagssaal) (see agenda item #33)" (PDF). landtag.li (in German). 6 March 2024. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- ^ "Liechtenstein: Parlament berät Vorlage zur Eheöffnung". Mannschaft Magazin. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ ""Ehe für Alle" ab 1. Januar 2025". Radio Liechtenstein (in German). Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ Flay Leichtenstein. "Danke fur 24x..." Facebook (in German). Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Landtag, 8. Marz 2024, Trakt. 31 (Teil 2) - 33 (watch from 33:58 onwards; results shown on 1:01:44)". vimeopro (in German). 8 March 2024.

- ^ "Art. 25 gekippt: Etappensieg für gleichgeschlechtliche Paare". Volksblatt (in German). 6 May 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "Art. 25 des Partnerschaftsgesetzes in Kraft - Ab heute dürfen auch homosexuelle Paare ein Stiefkind adoptieren)". vaterland.li (in German). 1 June 2023. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ "The Constitution of the Republic of Poland". Sejm RP. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

Marriage, being a union of a man and a woman, as well as the family, motherhood and parenthood, shall be placed under the protection and care of the Republic of Poland.

- ^ Judgment of the Supreme Court of 7 July 2004, II KK 176/04,

W dotychczasowym orzecznictwie Sądu Najwyższego, wypracowanym i ugruntowanym zarówno w okresie obowiązywania poprzedniego, jak i obecnego Kodeksu postępowania karnego, a także w doktrynie (por. wypowiedzi W. Woltera, A. Zolla, A. Wąska), pojęcie "wspólne pożycie" odnoszone jest wyłącznie do konkubinatu, a w szczególności do związku osób o różnej płci, odpowiadającego od strony faktycznej stosunkowi małżeństwa (którym w myśl art. 18 Konstytucji jest wyłącznie związek osób różnej płci). Tego rodzaju interpretację Sąd Najwyższy, orzekający w niniejszej sprawie, w pełni podziela i nie znajduje podstaw do uznania za przekonywujące tych wypowiedzi pojawiających się w piśmiennictwie, w których podejmowane są próby kwestionowania takiej interpretacji omawianego pojęcia i sprowadzania go wyłącznie do konkubinatu (M. Płachta, K. Łojewski, A.M. Liberkowski). Rozumiejąc bowiem dążenia do rozszerzającej interpretacji pojęcia "wspólne pożycie", użytego w art. 115 § 11 k.k., należy jednak wskazać na całkowity brak w tym względzie dostatecznie precyzyjnych kryteriów.

- ^ "Judgment of the Constitutional Tribunal of 11 May 2005, K 18/04".

Polska Konstytucja określa bowiem małżeństwo jako związek wyłącznie kobiety i mężczyzny. A contrario nie dopuszcza więc związków jednopłciowych. [...] Małżeństwo (jako związek kobiety i mężczyzny) uzyskało w prawie krajowym RP odrębny status konstytucyjny zdeterminowany postanowieniami art. 18 Konstytucji. Zmiana tego statusu byłaby możliwa jedynie przy zachowaniu rygorów trybu zmiany Konstytucji, określonych w art. 235 tego aktu.

- ^ "Judgment of the Constitutional Tribunal of 9 November 2010, SK 10/08".

W doktrynie prawa konstytucyjnego wskazuje się nadto, że jedyny element normatywny, dający się odkodować z art. 18 Konstytucji, to ustalenie zasady heteroseksualności małżeństwa.

- ^ "Judgment of the Supreme Administrative Court of Poland of 25 October 2016, II GSK 866/15".

Ustawa o świadczeniach zdrowotnych finansowanych ze środków publicznych nie wyjaśnia, co prawda, kto jest małżonkiem. Pojęcie to zostało jednak dostatecznie i jasno określone we wspomnianym art. 18 Konstytucji RP, w którym jest mowa o małżeństwie jako o związku kobiety i mężczyzny. W piśmiennictwie podkreśla się, że art. 18 Konstytucji ustala zasadę heteroseksualności małżeństwa, będącą nie tyle zasadą ustroju, co normą prawną, która zakazuje ustawodawcy zwykłemu nadawania charakteru małżeństwa związkom pomiędzy osobami jednej płci (vide: L. Garlicki Komentarz do art. 18 Konstytucji, s. 2-3 [w:] Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej. Komentarz, Wydawnictwo Sejmowe, Warszawa 2003). Jest wobec tego oczywiste, że małżeństwem w świetle Konstytucji i co za tym idzie – w świetle polskiego prawa, może być i jest wyłącznie związek heteroseksualny, a więc w związku małżeńskim małżonkami nie mogą być osoby tej samej płci.

- ^ "Judgment of the Supreme Administrative Court of Poland of 28 February 2018, II OSK 1112/16".

art. 18 Konstytucji RP, który definiuje małżeństwo jako związek kobiety i mężczyzny, a tym samym wynika z niego zasada nakazująca jako małżeństwo traktować w Polsce jedynie związek heteroseksualny.

- ^ *Gallo D; Paladini L; Pustorino P, eds. (2014). Same-Sex Couples before National, Supranational and International Jurisdictions. Berlin: Springer. p. 215. ISBN 978-3-642-35434-2.

the drafters of the 1997 Polish Constitution included a legal definition of a marriage as the union of a woman and a man in the text of the constitution in order to ensure that the introduction of same-sex marriage would not be passed without a constitutional amendment.

- Marek Safjan; Leszek Bosek, eds. (2016). Konstytucja RP. Tom I. Komentarz do art. 1-86. Warszawa: C.H. Beck Wydawnictwo Polska. ISBN 9788325573652.

Z przeprowadzonej powyżej analizy prac nad Konstytucją RP wynika jednoznacznie, że zamieszczenie w art. 18 Konstytucji RP zwrotu definicyjnego "związek kobiety i mężczyzny" stanowiło reakcję na fakt pojawienia się w państwach obcych regulacji poddającej związki osób tej samej płci regulacji zbliżonej lub zbieżnej z instytucją małżeństwa. Uzupełniony tym zwrotem przepis konstytucyjny "miał pełnić rolę instrumentu zapobiegającego wprowadzeniu takiej regulacji do prawa polskiego" (A. Mączyński, Konstytucyjne podstawy prawa rodzinnego, s. 772). Innego motywu jego wprowadzenia do Konstytucji RP nie da się wskazać (szeroko w tym zakresie B. Banaszkiewicz, "Małżeństwo jako związek kobiety i mężczyzny", s. 640 i n.; zob. też Z. Strus, Znaczenie artykułu 18 Konstytucji, s. 236 i n.). Jak zauważa A. Mączyński istotą tej regulacji było normatywne przesądzenie nie tylko o niemożliwości unormowania w prawie polskim "małżeństw pomiędzy osobami tej samej płci", lecz również innych związków, które mimo tego, że nie zostałyby określone jako małżeństwo miałyby spełniać funkcje do niego podobną (A. Mączyński, Konstytucyjne podstawy prawa rodzinnego, s. 772; tenże, Konstytucyjne i międzynarodowe uwarunkowania, s. 91; podobnie L. Garlicki, Artykuł 18, w: Garlicki, Konstytucja, t. 3, uw. 4, s. 2, który zauważa, że w tym zakresie art. 18 nabiera "charakteru normy prawnej").

- Scherpe JM, ed. (2016). European Family Law Volume III: Family Law in a European Perspective Family. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-78536-304-7.

Constitutional bans on same-sex marriage are now applicable in ten European countries: Article 32, Belarus Constitution; Article 46 Bulgarian Constitution; Article L Hungarian Constitution, Article 110, Latvian Constitution; Article 38.3 Lithuanian Constitution; Article 48 Moldovan Constitution; Article 71 Montenegrin Constitution; Article 18 Polish Constitution; Article 62 Serbian Constitution; and Article 51 Ukrainian Constitution.

- Stewart J, Lloyd KC (2016). "Marriage Equality in Europe". Family Advocate. 38 (4): 37–40.

Article 18 of the Polish Constitution limits the institution of marriage to opposite-sex couples.

- Marek Safjan; Leszek Bosek, eds. (2016). Konstytucja RP. Tom I. Komentarz do art. 1-86. Warszawa: C.H. Beck Wydawnictwo Polska. ISBN 9788325573652.

- ^ "IV SA/Wa 2618/18 – Wyrok WSA w Warszawie". 8 January 2019.

- ^ "Poland". travel.state.gov.

- ^ https://tranzycja.pl/krok-po-kroku/zmiana-danych-sad/

- ^ "Adopting in Slovakia". Community.

- ^ "Homophobia and Discrimination on Grounds of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the EU Member States Part II: The Social Situation" (PDF). fra.europa.eu.

- ^ Petit Press a.s. "Law change criminalises homophobia". spectator.sme.sk.

- ^ "Zakon o registraciji istospolne partnerske skupnosti". uradni-list.si (in Slovenian).

- ^ "Zakon o partnerski zvezi". uradni-list.si (in Slovenian).

- ^ "Implementation of the amendment to the Family Code". gov.si.

- ^ "First Adoption by Gay Partner of Child's Parent". The Slovenia Times. 20 July 2011. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ Weber, Nana (25 April 2013). "Sprememba spola v Sloveniji". Pravna Praksa (in Slovenian) (16–17). GV Založba. ISSN 0352-0730.

- ^ Hirschfeld, Magnus (10 March 2018). The Homosexuality of Men and Women. Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-61592-698-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ swissinfo.ch, S. W. I.; Corporation, a branch of the Swiss Broadcasting. "Homosexuals a step closer to equal rights". SWI swissinfo.ch.

- ^ swissinfo.ch, S. W. I.; Corporation, a branch of the Swiss Broadcasting. "Zurich grants gay couples more rights". SWI swissinfo.ch.

- ^ a b "Le pacs gagne du terrain".

- ^ "Bundesgesetz über die eingetragene Partnerschaft gleichgeschlechtlicher Paare". admin.ch (in German).

- ^ "Le nouveau droit de l'adoption entrera en vigueur le 1er janvier 2018". Le Conseil federal (in French). 10 July 2017. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ Schelhammer, Christoph R. "Diversité : « La société est tout sauf homogène. »". Swiss Army. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "Switzerland votes in favour of LGBT protection bill". bbc.com.

- ^ "Débureaucratisation de la procédure de changement de sexe à l'état civil dès le 1er janvier 2022". admin.ch (in French). Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ "Referendum in Armenia brings constitutional reforms". ILGA-Europe. 16 December 2015. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Armenia Central Electoral Commission announces constitutional referendum final results". Newsfeed. 13 December 2015. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Armenia: Gays live with threats of violence, abuse". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 30 March 2010. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ^ Prof. Dr. Axel Tschentscher, LL-M. "Belarus – Constitution". Servat.unibe.ch. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ^ "Belarus: Attitude towards homosexuals and lesbians in Belarus; state protection available to non-heterosexuals in Belarus with special attention to Minsk (2000–2005)". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 17 January 2006. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "Gay and Lesbian Issues in Belarus". A Belarus Miscellany. Archived from the original on 24 February 2001. Retrieved 29 September 2005.

- ^ "სსიპ "საქართველოს საკანონმდებლო მაცნე"".

- ^ "В Минобороны ответили на вопрос о сексуальных меньшинствах в армии". Tengrinews. 25 February 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ "The Constitution of Moldova" (PDF). The Government of Moldova. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ "Russian Gay History". community.middlebury.edu. Archived from the original on 26 July 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Russian parliament begins legalising ban on same-sex marriage". Reuters. 15 July 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Putin Signs Gender Reassignment Ban Into Law". The Moscow Times. 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "ЗАКОН". pravo.pmr-online.com.

- ^ "Study on homophobia, transphobia and discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity - Legal Report: Ukraine" (PDF). COWI. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ "Ukraine". travel.state.gov.

- ^ Garcia, Horaci (31 May 2022). "Ukraine's 'unicorn' LGBTQ soldiers head for war". Reuters. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine's gay soldiers fight Russia—and for their rights". The Economist. 5 April 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine's Parliament passes anti-discrimination law". Ukrinform. 12 November 2015. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ http://www.rferl.org/a/28340837.html

- ^ "Registration form". retsinformation.dk.

- ^ Stanners, Peter (7 June 2012). "Gay marriage legalised". The Copenhagen Post. Archived from the original on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ SØRENSEN, Kaare. "Homoseksuelle fik ja til ægteskab". Jyllands-Posten Politik. Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ "Lov om ændring af lov om registreret partnerskab, lov om en børnefamilieydelse og lov om børnetilskud og forskudsvis udbetaling af børnebidrag – Udvidet adgang for registrerede partnere til adoption og overførsel af forældremyndighed m.v. - retsinformation.dk".

- ^ "Børneloven af børneloven". Retsinformation (in Danish). Archived from the original on 30 April 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ Sweijs, Tim. "LGBT Military Personnel: a Strategic Vision for Inclusion". hcss.nl. The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ "MSN New Zealand – Latest News, Weather, Entertainment, Business, Sport, Technology". msn.co.nz.

- ^ (in Estonian) "Kooseluseadus". Riigikogu. 9 October 2014.