Macedonian grammar

The grammar of Macedonian is, in many respects, similar to that of some other Balkan languages (constituent languages of the Balkan sprachbund), especially Bulgarian. Macedonian exhibits a number of grammatical features that distinguish it from most other Slavic languages, such as the elimination of case declension, the development of a suffixed definite article, the lack of an infinitival verb, and the constructions with ima/nema formed with the auxiliary "to have", among others.

The first printed Macedonian grammar was published by Gjorgjija Pulevski in 1880.[1]

Orthography

The Macedonian orthography (правопис, pravopis) encompasses the spelling and punctuation of the Macedonian language.

Alphabet

The modern Macedonian alphabet was developed by linguists in the period after the Second World War, who based their alphabet on the phonetic alphabet of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, though a similar writing system was used by Krste Misirkov in the late 19th century. The Macedonian language had previously been written using the Early Cyrillic alphabet and later using Cyrillic with local adaptations from either the Serbian or Bulgarian alphabets.

The following table provides the upper and lower case forms of the Macedonian alphabet, along with the IPA value for each letter:

| Cyrillic IPA |

А а /a/ |

Б б /b/ |

В в /v/ |

Г г /ɡ/ |

Д д /d/ |

Ѓ ѓ /ɟ/ |

Е е /ɛ/ |

Ж ж /ʒ/ |

З з /z/ |

Ѕ ѕ /dz/ |

И и /i/ |

| Cyrillic IPA |

Ј ј /j/ |

К к /k/ |

Л л /ɫ/, /l/ |

Љ љ /l/ |

М м /m/ |

Н н /n/ |

Њ њ /ɲ/ |

О о /ɔ/ |

П п /p/ |

Р р /r/ |

С с /s/ |

| Cyrillic IPA |

Т т /t/ |

Ќ ќ /c/ |

У у /u/ |

Ф ф /f/ |

Х х /x/ |

Ц ц /ts/ |

Ч ч /tʃ/ |

Џ џ /dʒ/ |

Ш ш /ʃ/ |

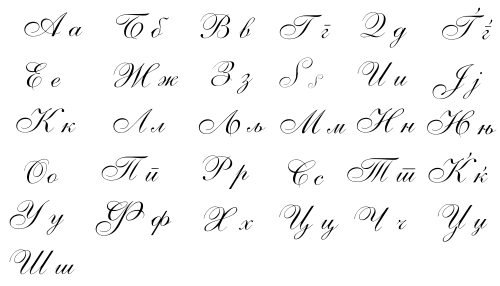

The cursive version of the alphabet is slightly different:

Punctuation

Punctuation (интерпункција, interpunkcija) marks are one or two part graphical marks used in writing, denoting tonal progress, pauses, sentence type (syntactic use), abbreviations, et cetera.

Marks used in Macedonian include periods (.), question marks (?), exclamation marks (!), commas (,), semicolons (;), colons (:), dashes (–), hyphens (-), ellipses (...), different types of inverted commas and quotation marks ( ‚‘, „“), brackets ((), [], {}) (which are for syntactical uses), as well as apostrophes (',’), solidi (/), equal signs (=), and so forth.

Syntax

The canonical word order of Macedonian is SVO (subject–verb–object), but word order is variable. Word order may be changed for poetic effect (inversion is common in poetry).

Generally speaking, the syntactic constituents of the language are:[2]:

- sentence or clause - the sentence can be simple and more complex.

- noun phrase or phrase - one or more words that function as single unit.

- complex sentence - a combination of two sentences and clauses.

- text - a set of sentences that are syntactically and semantically linked.

Morphology

Words, even though they represent separate linguistic units, are linked together according to the characteristics they possess. Therefore, the words in Macedonian can be grouped into various groups depending on the criteria that is taken into consideration. Macedonian words can be grouped according to the meaning they express, their form and their function in the sentence. As a result of that, there are three types of classification of the Macedonian words: semantic, morphological and syntactic classification.[3]

According to the semantic classification of the words, in the language there are eleven word classes: nouns, adjectives, numbers, pronouns, verbs, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, particles, interjections and modal words.[4]

Nouns, adjectives, numbers, pronouns and verbs belong to the open word class, whereas the prepositions, adverbs, conjunctions, particles, interjections and modal words belong to the closed word class. This is the morphological classification of the words. Finally, there are two large groups according to the syntactic classification. The larger part of the words belong to group of lexical words, and such words are: nouns, adjectives, numbers, pronouns, verbs, adverbs and modal words. The prepositions, conjunctions, particles and interjections belong to the group of function words[5].

Nouns

Macedonian nouns (именки, imenki) belong to one of three genders (masculine, feminine and neuter) and are inflected for number (singular and plural), and marginally for case. The gender opposition is not distinctively marked in the plural.[6]

The Macedonian nominal system distinguishes two numbers (singular and plural), three genders (masculine, feminine and neuter), case and definiteness. Definiteness is expressed by three definite articles pertaining to the position of the object (unspecified, proximal, and distal) which are suffixed to the noun.

Definiteness

The article (член, člen) is postfixed, as in Bulgarian, Albanian and Romanian. In Macedonian there is only the definite article. One feature that has no parallel in any other standard Balkan language[2] is the existence of three definite articles pertaining to position of the object: medial and/or unspecified, proximal (or close) and distal (or distant).

| The definite articles | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |||||

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | |

| Medial | −от (−ot) | −та (−ta) | −то (−to) | −те (−te) | −те (−te) | −та (−ta) |

| Proximal | −ов (−ov) | −ва (−va) | −во (−vo) | −ве (−ve) | −ве (−ve) | −ва (−va) |

| Distal | −он (−on) | −на (−na) | −но (−no) | −не (−ne) | −не (−ne) | −на (−na) |

Examples:

- Јас го видов човекот (Jas go vidov čovekot, 'I saw the man', medial): the subject, 'man', is either close to the interlocutor or its position is unspecified;

- Јас го видов човеков (Jas go vidov čovekov, 'I saw this man', proximal; "and only this man"): the subject, 'man', is close to the speaker (and possibly the interlocutor(s) as well);

- Јас го видов човекон (Jas go vidov čovekon, 'I saw that man', distal; "and only that man"): the subject, 'man', is far from both the speaker and the interlocutor(s).

In the masculine singular, −от/−ов/−он is used after a consonant, −та/−ва/−на after −а (e.g. судијата 'the judge'), and −то/−во/−но after a vowel other than −а (e.g. таткото 'the father').

Vocative case

Macedonian lost the traditional (Slavic) grammatical cases during its development and became an analytic language. The case endings were replaced with a complex system of prepositions; however, there are still some traces left of the vocative case in contemporary Macedonian. The vocative case is formed by adding the endings '–o' or '–e' (for feminine nouns), '–u' (for masculine monosyllabic nouns), and '–e' (for masculine polysyllabic nouns). For example, пријател [ˈprijatɛɫ] ('friend') takes the form of пријателе [priˈjatɛlɛ] ('friend!').[3] The vocative is used almost exclusively for singular masculine and feminine nouns.

Pronouns

Macedonian pronouns decline for case ('падеж'), i.e., their function in a phrase as subject (ex. јас 'I'), direct object (него 'him'), or object of a preposition (од неа 'from her').

Based on their meaning and their function in a sentence, pronouns fall into one of the following categories:

| Types of pronouns | Examples |

|---|---|

| Demonstrative pronouns | ова (ova, 'this'), она (ona, 'that'), овде (ovde, 'here'), таму (tamu, 'there') |

| Indefinite pronouns | некој (nekoj, 'somebody'), нешто (nešto, 'something') |

| Interrogative pronouns | кој (koj, 'who'), кого/ кому (kogo/ komu, 'whom'), што (što, 'what') |

| Personal pronouns | јас (jas, 'I'), ти (ti, 'you'), тој (toj, 'he'), таа (taa, 'she'), тоа (toa, 'it'), ние (nie, 'we') |

| Possessive pronouns | мој (moj, 'my'), твој (tvoj, 'your'), нејзин (nejzin, 'her'), негов (negov, 'his'), наш (naš, 'our') |

| Relative pronouns | кој (koj, 'who'), којшто (kojšto, 'which'), што (što, 'that'), чиј (čij, 'whose'), чијшто (čijšto, 'whose') |

| Reflexive pronoun and reciprocal pronouns |

себе (sebe, 'himself, herself'), сe (se, 'self') |

| Universal pronouns | сите (site, 'all'), секој (sekoj, 'everybody', 'each'), сѐ (se, 'everything'), секаде (sekade, 'everywhere') |

Verbs

Macedonian has a complex system of verbs (глаголи, glagoli). Generally speaking Macedonian verbs have the following characteristics, or categories as they are called in the Macedonian studies: tense, mood, person, type, transitiveness, voice, gender, and number.

According to the categorization, all Macedonian verbs are divided into three major subgroups: a-subgroup, e-subgroup and i-subgroup. Furthermore, the e-subgroup is divided into three more subgroups: a-, e- and i-subgroups. This division is done according to the ending (or the last vowel) of the verb in the simple present, singular, third person.[7]

Simple verb forms

Present tense

The Present tense (сегашно време, segašno vreme) is used to express present actions and actions that overlap with the moment of speaking and this meaning is expressed with the use of imperfective verbs. Besides that, the Present tense can be formed with the perfective verbs as well, but then it is not true present action, but more likely future in the past. Besides the present action, with the forms of present tense there is possibility to express[8]:

- past events - the forms are the same, but the meaning refers to certain past event. This usually occurs when telling stories or retelling events.

- future events - the forms are the same, but the meaning refers to the future. Usually, these types of events are time-table or schedule of tasks that are planned.

- general facts - expressing common knowledge that is always same.

- routines and habits

- expressing preparedness and events that occur at same time - the speaker expresses that (s)he is ready to do certain tasks and expressing two actions that occur at the same time.

The forms of the Present simple in Macedonian are made by adding suffixes to the verb stems. In the following tables are shown the suffixes that are used in Macedonian and one example for each verb subgroup.

Here are some examples where the usage of Present tense in Macedonian is applied:

- Јас јадам леб. (Jas jadam leb., 'I eat bread.')

- Додека тој јаде, ти чисти ја собата. (Dodeka toj jade, ti čisti ja sobata., 'While he eats, you clean the room.')

- Автобусот за Скопје тргнува во 5 часот. (Avtobusot za Skopje trgnuva vo 5 časot., 'The bus for Skopje leaves at 5 o'clock.')

- Ако ја грееш водата, таа врие. (Ako ja greeš vodata, taa vrie., 'If you heat the water, it boils.')

- Секој ден јас гледам сериски филм. (Sekoj den jas gledam seriski film., 'Every day I watch a serial film.')

Imperfect

The imperfect, or referred to as 'past definite incomplete tense' (минато определено несвршено време,minato opredeleno nesvršeno vreme), is used to express past actions where the speaker is a witness of it or took participation in it. In order to express such an action or state, imperfective verbs are used. Also, there is a possibility to express an action with perfective verbs, but then before the verb there should be some of these prepositions or particles: ако (ako, 'if'), да (da, 'to') or ќе (ḱe, 'will'). It is important to mention that when perfective verbs are used, then there is expression of conditional mood, past-in-the-future or other perfective aspects, but not witnessed past actions. Besides the basic usage of the Imperfect, with this tense in Macedonian can be expressed and[9]:

- conditional mood - as it is mentioned with perfective verbs,

- weak command - usually a polite request,

- past actions that were repeated for some period

- preparedness - the speaker expresses that (s)he is ready to do certain tasks.

As an exemplification of the mentioned usages, here are some sentences:

- Јас ловев зајаци. (Jas lovev zajaci., 'I was hunting rabbits.')

- Ако не брзаше, ќе немаше грешки. (Ako ne brzaše, ḱe nemaše greški., 'If you weren't rushing, you would not make mistakes.')

- Да ми помогнеше малку? (Da mi pomogneše malku?, 'What about helping me a bit?')

- Секој ден стануваше во 7 часот и готвеше кафе. (Sekoj den stanuvaše vo 7 časot i gotveše kafe., 'He was getting up every day at 7 o'clock and making coffee.')

Aorist

The aorist, also known as 'past definite complete tense' (минато определено свршено време, minato opredeleno svršeno vreme), is a verb form that is used to express past finished and completed action or event, with or without the speaker's participation in it. The duration of the action that is expressed with the aorist can be long or short. For aorist, in Macedonian are used perfective verbs, but sometimes, though very rarely, in non-standard folk speech there may be usage of imperfective verbs. Besides this basic usage, the aorist also can be used to express:[11]

- future event - the form is standard aorist, but the meaning refers to the future, usually near future as a consequence of the previous action.

- condition - past condition

- general fact - rarely used, usually in popular proverbs.

The formation of the aorist for most verbs is not complex, but there are numerous small subcategories which must be learned. While all verbs in the aorist (except сум) take the same endings, there are complexities in the aorist stem vowel and possible consonant alternations. [12]

| singular | plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | − в − v |

− вме − vme |

| 2. | ∅ | − вте − vte |

| 3. | ∅ | − а / − ја − a / − ja |

Note: ∅ indicates a zero ending. The suffix -ja is used for verbs of the I-division of I-subgroup and for the division of E-subgroup without vowel, i.e. izmi - izmija (wash - washed)

The following tables show the paradigm of the aorist for all three major verb subgroups and their divisions:

In the following section are given some examples about the mentioned usage above:

- Ние прочитавме книга. (Nie pročitavme kniga, 'We read a book.')

- Го положив ли испитот, те честам пијачка. (Go položiv li ispitot, te čestam pijačka., 'Should I pass the exam, I'll treat you to a drink.')

- Една вечер спав надвор. (Edna večer spav nadvor., 'One night I slept outside.')

Complex verb forms

Perfect of perfective verbs

The Macedonian tense минато неопределено свршено време (minato neopredeleno svršeno vreme, 'past indefinite complete tense'), or referred to as 'perfect of perfective verbs', functions similarly as the English Present perfect simple. The forms of the Macedonian present perfect are formed with the forms of 'to be' in present tense plus the L-form of the conjuncted verb, which is always perfective. Important to note is that for third person singular there is no presence of the verb 'to be'.[13] This form of the Macedonian perfect is sometimes called 'sum-perfect'. The conjugation of one perfective verb in Macedonian looks as the following one, which is the verb прочита (pročita, 'read'):

| singular | plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Јас сум прочитал Jas sum pročital |

Ние сме прочитале Nie sme pročitale |

| 2. | Ти си прочитал Ti si pročital |

Вие сте прочитале Vie ste pročitale |

| 3. | Тој прочитал Toj pročital Таа прочитала Taa pročitala Тоa прочиталo Toа pročitalо |

Тие прочитале Tie pročitale |

As an example of this tense:

Јаc

Jas

I

сум

sum

am

ја

ja

it (clitic)

прочитал

pročital

read

книгата.

knigata.

book-the

"I have read the book"

Macedonian developed an alternative form of the sum-perfect, which is formed with the auxiliary verb 'to have' and a verbal adjective in neutral, instead of the verb 'to be' and verbal l-form. This is sometimes called 'ima-perfect'.

| singular | plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Јас имам прочитано Jas imam pročitano |

Ние имаме прочитано Nie imame pročitano |

| 2. | Ти имаш прочитано Ti imaš pročitano |

Вие имате прочитано Vie imate pročitano |

| 3. | Тој има прочитано Toj ima pročitano Таа има прочитано Taa ima pročitano Тоa има прочитано Toа ima pročitano |

Тие имаат прочитано Tie imaat pročitano |

There is a slight difference in meaning between 'sum-perfect' and 'ima-perfect'.

Perfect of imperfective verbs

The English tense 'Present perfect continuous' functions similarly as the Macedonian tense минато неопределено несвршено време (minato neopredeleno nesvršeno vreme, 'past indefinite incomplete tense') or known as 'perfect of imperfective verbs'. This perfect tense is formed similarly as the perfect of perfective verbs i.e. with the present tense forms of 'to be' and the L-form of the conjuncted verb, but this time the verb is imperfective. Important to note is that for third person singular there is no presence of the verb 'to be'.[14] The conjugation of one imperfective verb in Macedonian looks as the following one, which is the verb чита (read):

| singular | plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Јас сум читал Jas sum čital |

Ние сме читале Nie sme čitale |

| 2. | Ти си читал Ti si čital |

Вие сте читале Vie ste čitale |

| 3. | Тој читал Toj čital Таа читала Taa čitala Тоa читалo Toа čitalо |

Тие читале Tie čitale |

As an example of this tense:

Јаc

Jas

I

сум

sum

am

ја

ja

it (clitic)

читал

čital

read

книгата.

knigata.

book-the

"I have been reading the book"

Like the perfect of perfective verbs, Macedonian also developed an alternative form of the sum-perfect, which is formed with the auxiliary verb 'to have' and a verbal adjective in neutral, instead of the verb 'to be' and verbal l-form. This is sometimes called 'ima-perfect'.

| singular | plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Јас имам читано Jas imam čitano |

Ние имаме читано Nie imame čitano |

| 2. | Ти имаш читано Ti imaš čitano |

Вие имате читано Vie imate čitano |

| 3. | Тој има читано Toj ima čitano Таа има читано Taa ima čitano Тоa има читано Toа ima čitano |

Тие имаат читано Tie imaat čitano |

There is also a slight difference in meaning between 'sum-perfect' and 'ima-perfect' regarding perfect of imperfective verbs. Ima-perfect usually denotes resultative meaning.

Future tense

With the forms of future tense in Macedonian are expressed actions that are planned to happen in future. Usually, when we speak about future, we mean expressing events that should happen soon, however, there is a special form in Macedonian to express future events from past perspective, or event that happened after some other event and this is treated as separate tense called 'Future-in-the-past'.

The simple future tense is formed by adding the clitic ќе (ḱe, 'will') to the inflected present tense form of the verb. In this respect, both Macedonian and Bulgarian differ from other South Slavic languages, since in both the clitic is fixed, whereas in Serbo-Croatian it inflects for person and number [15]. The negative form of the future tense in Macedonian is made by adding the particles нема да (nema + da) or just не (ne) before the verb pattern, whereas the interrogative form is made by adding the question word дали (dali), also before the verb pattern. When we use the negative form nema da, there is not presence of the clitic ḱe. Usually, ḱe in English is translated with the modal verb 'will', and vice versa. When an event is expressed with the use of ḱe, then it is considered normal future, but there is a stronger future event as well which is made with the construction: има (ima, 'have') + да ('da', 'to') + present simple form of the verb[16].

| игра (igra, play) affirmative |

носи (nosi, bring) ne-negation |

везе (veze, embroider) nema da-negation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Јас I |

ќе играм ḱe igram |

не ќе носам ne ḱe nosam |

нема да везам nema da vezam |

| Ти You |

ќе играш ḱe igraš |

не ќе носиш ne ḱe nosiš |

нема да везеш nema da vezeš |

| Тој, таа, тоа He, she, it |

ќе игра ḱe igra |

не ќе носи ne ḱe nosi |

нема да везе nema da veze |

| Ние We |

ќе играме ḱe igrame |

не ќе носиме ne ḱe nosime |

нема да веземе nema da vezeme |

| Вие You |

ќе играте ḱe igrate |

не ќе носите ne ḱe nosite |

нема да везете nema da vezete |

| Тие They |

ќе играат ḱe igraat |

не ќе носат ne ḱe nosat |

нема да везат nema da vezat |

Besides the main usage, the future tense is used to express[17]:

- past events - expressing events that somehow refer to the future,

- orders - giving orders or commands to someone,

- prediction - predicting something,

- general facts - usually for proverbs or things that are considered as facts,

- events that repeat after some period,

- possibility - possible future events.

Some of these mentioned rules, can be recognized in the following examples:

- Јас ќе одам во Скопје. (Jas ḱe odam vo Skopje) – I will go to Skopje.

- Јас отидов во визбата и што ќе видам, сето вино истекло на подот. (Jas otidov vo vizbata i što ḱe vidam, seto vino isteklo na podot., 'I went to the basement and, lo and behold, all of the wine was spilled on the floor.')

- Ќе ме слушаш и ќе траеш. (Ḱe me slušaš i ḱe traeš., 'You will listen to me and you will say no words.')

- Колку е стар твојот дедо? Ќе да има 70 години. (Kolku e star tvojot dedo? Ḱe da ima 70 godini., 'How old is your granddad? He'd have to be [at least] 70 years old.')

- Ќе направам сѐ само да се венчам со Сара. (Ḱe napravam sè samo da se venčam so Sara., 'I'd do anything just to marry Sara.')

- Ќе одиш на училиште и крај! (Ḱe odiš na učilište i kraj!, 'You will go to school, and that’s it!')

Future-in-the-past

Future-in-the-past is expressed by means of the same clitic ќе (ḱe, 'will') and past tense forms of the verb:

| ќе | доjдеше |

| ḱe | dojdeše |

| will (clitic) | he came (imperfective aspect) He would come/he would have come. |

An interesting fact of vernacular usage of a past tense form of the verb which can be used in a future sense as well, although this construction is mostly limited to older speakers, and is used to describe the degree of certainty that some event will take place in the future or under some condition. This characteristic is shared with Croatian, Bosnian, Montenegrin and Serbian languages.

Examples:

- Те отепав, штом те фатам. (Te otepav, štom te fatam., 'I have killed you, when I get you')

- Те фатам ли, те казнив. (Te fatam li, te kazniv., 'As soon as I grab you, I have punished you')

In this respect, Macedonian is different from Bulgarian: Macedonian is consistent in the use of ќе as a clitic, whereas the equivalent Bulgarian construction involves the inflection of the clitic for tense, person and number as a regular verb (щях да дойда, 'I would [have] come'; щеше да дойде, 'he would [have] come').

Adjectives

Adjectives (придавки, pridavki) agree with nouns in gender, number and definiteness with their noun and usually appear before it.

Comparison

Adjectives have three degrees of comparison (степенување на придавки, stepenuvanje na pridavki) – positive, comparative and superlative. The positive form is identical to all the aforementioned forms. The other two are formed regularly, by prepending the particle по and the word нај directly before the positive to form the comparative and superlative, respectively, regardless of its comprising one or two words.

| Positive | Comparative | Superlative |

|---|---|---|

| тежок (heavy) | потежок (heavier) | најтежок (heaviest) |

| долг (long) | подолг (longer) | најдолг (longest) |

Macedonian only has one adjective that has an irregular comparative – многу.

| Positive | Comparative | Superlative |

|---|---|---|

| многу (a lot) | повеќе (more) | најмногу (the most) |

A subtype of the superlative – the absolute superlative – also present in some other South Slavic languages and Romance languages (such as Italian and Spanish), expresses the highest quality without comparison. It is formed by prefixing the particle пре (pre) to an adjective, roughly corresponding to the English 'very + adjective' or 'too + adjective' combinations.

Prepositions

Prepositions (предлози, predlozi) are part of the closed word class that are used to express the relationship between the words in a sentence. Since Macedonian lost the case system, the prepositions are very important for creation and expression of various grammatical categories. The most important Macedonian preposition is на (na, 'of', 'on' or 'to'). Regarding the form, the prepositions can be: simple (vo, na, za, do, so, niz, pred, zad, etc.) and complex (zaradi, otkaj, nasproti, pomeǵu, etc.). Based on the meaning the preposition express, they can be divided into:[18][19][20]

| Type | Prepositions | Example | Question words |

|---|---|---|---|

| prepositions of place | на [na] ('on'), под [pɔd] ('under'), etc. | Топката е под масата. The ball is under the table. |

They can be determined by the question word каде [ˈkadɛ] ('where'). |

| prepositions of time | ќе [cɛ] ('will'), во [vɔ] ('in', 'at'), etc. | Тој беше во Тетово во 1999. He was in Tetovo in 1999. |

They can be determined by the question word кога [ˈkɔɡa] ('when'). |

| prepositions of manner | на [na] ('on'), со [sɔ] ('with'), etc. | Тој го кажа тоа со иронија. He said that with irony. |

They can be determined by the question word како [ˈkakɔ] ('how'). |

| prepositions of quantity | многу [ˈmnɔɡu] ('a lot'), малку [ˈmalku] ('a few'), etc. | Тој научи малку англиски зборови. He learned a few English words. |

They can be determined by the question word колку [ˈkɔlku] ('how much/ how many'). |

Having in mind the fact that the preposition "на" is the most frequently used in the language, it may be used to express different meaning[21][22]:

- time, e.g. Штрковите на зима се преселуваат на југ. (Štrkovite na zima se preseluvaat na jug., 'The storks move to south in winter.')

- manner, e.g. Тој на шега го удри пријателот. (Toj na šega go udri prijatelot., 'He hit the friend for fun.')

- purpose, e.g. Ние ќе одиме на скијање. (Nie ḱe odime na skijanje., 'We will go skiing.')

- possession, e.g. Таа е сестрата на Марко. (Taa e sestrata na Marko., 'She is the sister of Marko.')

- comparison, e.g. Детено многу личи на брат му. (Deteno mnogu liči na brat mu., 'That child looks like his brother, a lot.')

Particles

The particles (честички, čestički) are closed word class that have grammatical function. The particles are used to determine other words, form some grammatical categories and emphasize some words or phrases. Regarding the function of the particles, they can be divided into the following groups: [23][24]

- particles used to emphasize something

- e.g. барем [ˈbarɛm] ('at least'), само [ˈsamɔ] ('just'), сѐ [sɛ] ('all'), etc.

- particles used to separate a person or an object from a larger group

- e.g. само [ˈsamɔ] ('only'), единствено [ɛˈdinstvɛnɔ] ('solely'), исклучиво [isˈklut͡ʃivɔ] ('only'), etc.

- particles for joining things

- e.g. исто [ˈistɔ] ('same'), исто така [ˈistɔ taka] ('also'), притоа [ˈpritɔa] ('besides that'), etc.

- particles for quantity

- e.g. речиси [ˈrɛt͡ʃisi] ('almost'), скоро [ˈskɔrɔ] ('almost', 'nearly'), точно [ˈtɔt͡ʃnɔ] ('right'), рамно [ˈramnɔ] ('equal'), etc.

- particles for exact determination of something

- e.g. имено [ˈimɛnɔ] ('namely'), токму [ˈtɔkmu] ('precisely'), etc.

- particles for approximate determination of something

- e.g. −годе [-ɡɔdɛ], −било [-bilɔ], − да е [da ɛ]. These particles should be combined with other words, they do not stand on their own.

- particles for indication of something

- e.g. еве [ˈɛvɛ] ('here'), ене [ˈɛnɛ] ('there), ете ˈɛtɛ ('there'), etc.

- particles for negative sentences

- e.g. не [nɛ] ('no', 'not'), ниту [ˈnitu] ('neither'), нити [ˈniti] ('neither') and ни [ni] ('nor').

- particles for interrogative sentences

- e.g. ли [li], дали [ˈdali], зар [zar], али [ˈali] and нели[ˈnɛli] (question tag)

- particles for imperative sentences

- e.g. да [da] ('to') and нека [ˈnɛka] ('let')

Numerals

The Macedonian numbers (броеви, broevi) have gender and definiteness. The first ten cardinal and ordinal numerals in the Macedonian are:

Phraseology

The group of words that are used in the language as one unit, word construction, are called phraseological units or in Macedonian фразеологизми (frazeologizmi). The phraseological units have special linguistic characteristics and meaning. Within one sentence, the words may be joined in order to create units of various types. For instance, the word nut can be combined with many adjectives, such as big nut, small nut etc. Moreover, the word nut can be combined with other parts of speech as well, such as with verbs as in the sentence I ate a nut. [25]

These types of combinations are led by the general principles of the phraseology, which states that the words in the sentences can be freely combined. Within these combinations or collocations, each word keeps its original meaning, so the meaning of the whole construction is equal to the meaning of its constituents.[26]

Besides the word construction with loose connections, in Macedonian there are word constructions that are not freely combined, which means they are permanently combined. As an illustration of these two types of connections are the following sentences, where the noun phrase "hard nut" is used[27]:

- It is a hard nut and it cannot be cracked easily.

- We will be hard nut for our opponent.

In the first sentence, "hard nut" is a common collocation, where the words are connected freely and can be changed with other words in different contexts. On the other hand, in the second sentence the noun phrase "hard nut" (i.e. a hard nut to crack) is an expression that means "strong, unbreakable" and the words are in strong connection and they are not changed with other words. If these words are changed, the meaning of the phrase will be lost.

Onomastics

Macedonian onomastics (Macedonian: Македонска ономастика, romanized: makedonska onomastika) is a part of Macedonian studies, which studies the names, surnames and nicknames of the Macedonian language and people. This is relatively new linguistic discipline. In Macedonia, and in Macedonian studies in general, it developed during the 19th century, where the first few research results have been provided. The Onomastics for a long period of time has been considered as part of various different scientific disciplines, such as Geography, History or Ethnography, until it became a discipline on its own in the 20th century. The Macedonian Onomastics, generally speaking, is divided into toponomastics and anthroponomastics.[28]

See also

Notes

- ^ Gjorgjija Pulevski Archived 2008-04-15 at the Wayback Machine on the site of MANU.

- ^ Standard Bulgarian has only the unspecified form, although three definite article forms exist in certain Bulgarian dialects, notably the vernaculars of Tran and parts of the Rhodopes [1].

- ^ Compare with other languages in the Balkan sprachbund; Bulgarian: приятел and приятелю; Serbo-Croatian: prijatelj and prijatelju; Greek: φίλος and φίλε; Romanian: prieten and prietene.

References

- ^ Christina E. Kramer (1999), Makedonski Jazik (The University of Wisconsin Press).

- ^ Friedman, V. (2001) Macedonian (SEELRC), p. 17.

- ^ Friedman, V. (2001) Macedonian (SEELRC), p. 40.

- ^ Lunt, H. (1952) Grammar of the Macedonian Literary Language, Skopje.

- ^ Tomić, O. (2003) "Genesis of the Balkan Slavic Future Tenses" in Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics: The Ottawa Meeting 2003 (Michigan : Michigan Slavic Publications).

- ^ Бојковска, Стојка; Минова-Ѓуркова, Лилјана; Пандев, Димитар; Цветковски, Живко (December 2008). Саветка Димитрова (ed.). Општа граматика на македонскиот јазик. Скопје: АД Просветно Дело. OCLC 888018507.

- ^ Стојка Бојковска; Димитар Пандев; Лилјана Минова - Ѓуркова; Живко Цветковски (2001). Македонски јазик за средно образование. Скопје: Просветно Дело АД.

- ^ Кепески, К. (1946), Македонска граматика, Скопје, Државно книгоиздавателство на Македонија.

- ^ Конески, Блаже (1967). Граматика на македонскиот литературен јазик. Скопје: Култура.

- ^ Стойков, С. (2002) Българска диалектология, 4-то издание. стр. 127. Also available online.

External links

- Slognica rečovska, the first printed Macedonian grammar by Gjorgjija Pulevski in 1880.

- Macedonian grammar by Victor Friedman.

- Grammar of the Literary Macedonian language by Horace Lunt.

- Macedonian grammar by Krume Kepeski.